300 wk3

WEEK 3: Scientific Method, Reasoning and Hypotheses

Lesson

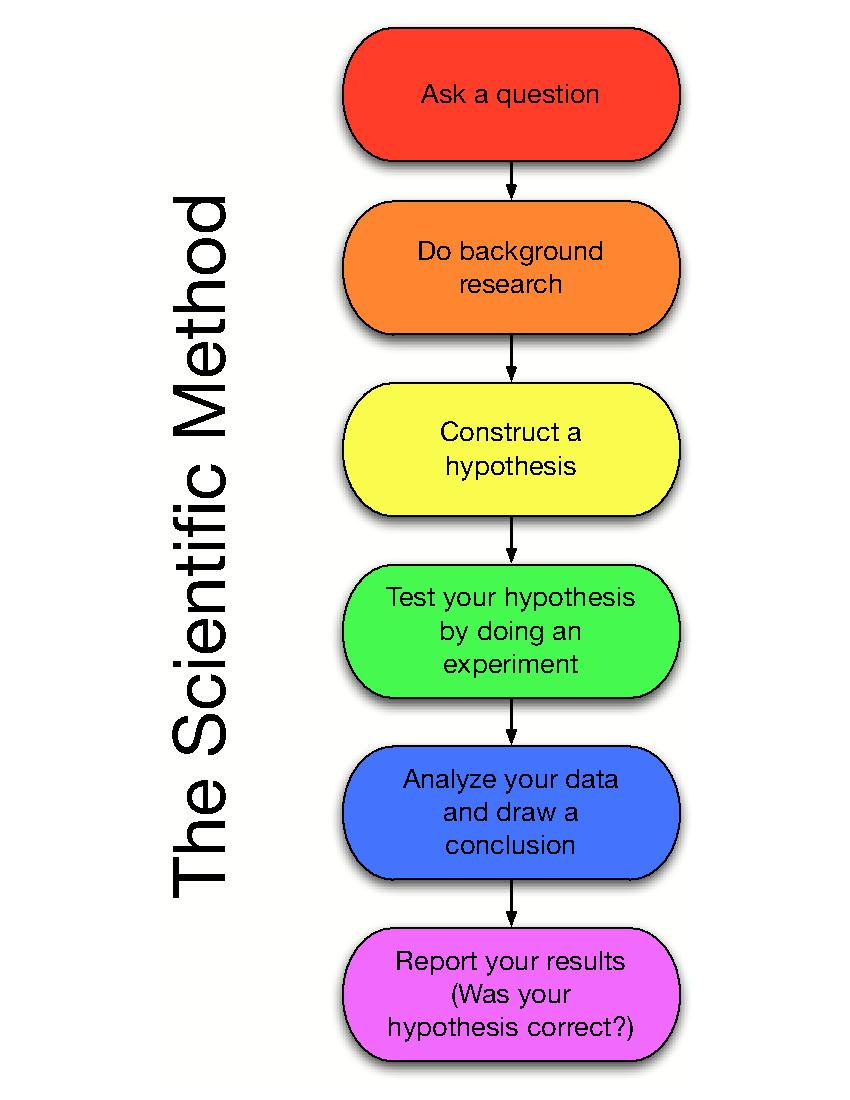

Last week you developed a research question and found some references in the online Library to support your research. This week we will talk about the foundations of research methodology. The basic “building block” of research of any type is the scientific method.

Source of diagram: science-lab.wikispaces.com

So what exactly is the “scientific method”? Traditionally, the scientific method is a means by which researchers gain insight into what was previously unknown using a standardized set of techniques for building scientific knowledge, such as how to identify a problem, posit a hypothesis, gather data and interpret results and, finally, draw conclusions.

A theory that results from the scientific method must satisfy four characteristics:

The result must be repeatable. That is, others should be able to independently replicate or repeat the scientific study and obtain similar, if not identical, results.

The result must be precise. The theoretical concepts, which are often hard to measure, must be defined with sufficient precision that others can use those definitions to measure concepts and test the theory.

The result must be falsifiable. That is, a theory must be stated in a way that it can be disproven.

Finally, the resulting theory should be parsimonious, simple in its explanation of a phenomenon. Parsimony prevents researchers from pursuing endless concepts and relationships that explain everything in general but nothing in specific.

While man can make use of procedures found in methods, the most important research tool is the human mind, which is capable of great powers of comprehension, the ability to make finite linear and non-linear connections, and intuitive logic and insight. Human beings have developed strategies of reasoning to help them better understand the unknown. The next section will describe and compare deductive logic and inductive reasoning.

In logic, we often refer to the two broad methods of reasoning as the deductive and inductive approaches.

Deductive logic begins with one or more premises. Premises are “statements or assumptions that are self-evident and widely accepted truths”. This type of reasoning applies general rules to particular cases. For example:

X nation always closes down ports and declares exclusion zones before they conduct missile testing.

X nation issues a no go zone warning and shuts down its ports.

X nation is likely to be preparing for a missile test.

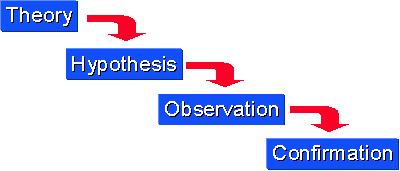

If a missile test does occur, then the theory is confirmed. If a missile test does not occur, one would question the original premise, or consider an alternative deduction from that particular action. In deduction, theory precedes observation. Deductive logic is extremely valuable for generating research hypotheses and testing theories. (Leedy 2005, 31-2)

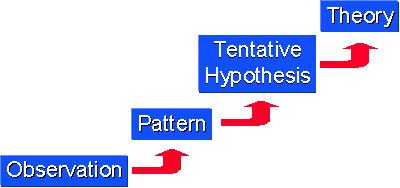

Inductive reasoning begins, not with an established truth or premise, but with an observation. In inductive reasoning, people use observations of specific events to draw conclusions. In induction, observation precedes theory. The researcher observes an event of interest and records those observations. After a study of his observations, the researcher notices a pattern or regularity in the data and develops a theory to explain why the pattern has occurred. For example:

Palestinians shell Jewish settlements in Gaza when peace talks break down

Israelis respond with strikes on Palestinian compounds in Gaza.

When peace talks break down, subsequent violent actions by Palestinians against Israelis elicit retributory strikes against Palestinians.

Source of diagrams: Research Methods Knowledge Base http://www.socialresearchmethods.net/kb/dedind.php

So far, we have identified a research questions and discussed the scientific method and basic types of reasoning. The next step in progressing toward a hypothesis is to propose some explanations for the phenomenon and identify other factors in direct relationships with it, and diagram them out in such a way that they lead the researcher to a clear statement that indicates how he thinks the phenomena are related.

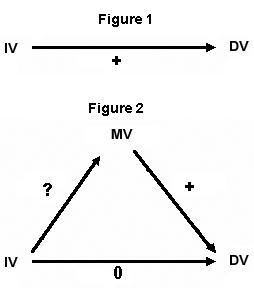

A phenomenon that will help to explain the behavior or event that interests us is termed an “independent variable”(IV). Independent variables are “causal” variables in that they have an effect, influence or cause some other phenomena directly related to the “dependent variable”(DV), which is caused or depends on the influence of independent and other variables. The diagram below provides a simple arrow diagram:

Figure 1 represents the simplest relationship between cause and effect. As the researcher defines more variables that have causal or influential relationships to the dependent variable, the arrow diagram can become more complicated and informative. In Figure 2, the diagram illustrates the influence of a “mediating variable” (MV) whose relationship with the other independent variable is not clear (hence the ”?”) however, the MV does influence the dependent variable. There are other types of variables that influence an outcome. Those influences that precede an IV are called “antecedent variables” (AV). A variable that occurs closer in time to the dependent variable but is also influenced by the IV is called an “intervening variable” (IV). For example, in the simple statement that, “Sunshine causes photosynthesis, which causes grass to grow”, sunshine is an IV, photosynthesis is an intervening variable, and the dependent variable is the growing grass.

The next step is to formulate a hypothesis. A hypothesis is an “explicit statement that makes an educated guess about existing relationships”. (Johnson 1995, 56) We formulate hypotheses in our everyday thinking about events. For example, if we wonder why there are revolutions occurring in the Arab countries, and we decide that it is because the population is unemployed, frustrated with the unfair distribution of wealth and power, and lacking a democratic process to change their conditions, we are proposing a hypothesis relating employment, wealth distribution, the countries’ political process to political instability and unrest.

Characteristics of a good hypothesis:

It is should be an empirical statement; that is, it should be educated guess about relationships that exist in the real world, not a statement about what ought to be true (normative).

It should be general, explaining a general phenomenon rather than one occurrence.

It should be plausible, the result of some logical thinking. Since it is an educated guess, the researcher cannot know if it will be confirmed or not; however, it should be reasonable.

It should be specific in stating the proposed relationship between variables, and be clear and focused.

It should be consistent with the data and the method that the researcher plans to use to test the hypothesis.

It should be testable, meaning that there must be some evidence that the researcher can find that will prove or disprove the hypothesis.

References:

Leedy, Paul D and Jeanne Ormrod. 2005. Practical Research Planning and Design. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson.

Johnson, Janet Buttolph and Richard Joslyn. 1995. Political Science Research Methods. Washington, DC: CQ Press.

Johnson, Janet Buttolph, H.T. Reynolds and Jason Mycoff. 2008. Political Science Research Methods, Sixth Edition. Washington, DC: CQ Press.