homwork michaelsmith

Chapter 3: Micro Foundations of Firm’s Advantage – Dynamic Capabilities View

In a previous chapter, we learnt about resource-based view (RBV), knowledge-based view (KBV) and core competence view (CCV) hypotheses. A major limitation of these hypotheses is that they are not designed for the VUCA world – the world that is volatile, uncertain, complex and ambiguous. Therefore, they do not consider the entropy factors – the factors that act as disruptive forces in highly dynamic markets. In this chapter, we will examine three of the most important entry factors:

mainstreaming of non-consumers, i.e. the rise of new groups of customers served using alternative sets of resources, knowledge and/or core competencies.

political power play, i.e. the role of non-market – often government-supported - factors in enabling competing firms to develop alternative sets of resources, knowledge and/or core competencies.

globalization games, i.e. the shifts in the advantages of different national markets, and as a consequence of the firms having investments in those markets.

Micro foundations of firm’s advantage refer to the structures, processes and behaviors that help firms navigate the VUCA world. Development of appropriate structures, processes and behaviors that are in tune with the VUCA world allows firms to be dynamic in their capability. Dynamic capability is the capability for recognizing and responding or adapting to significant market change. Dynamic capability view (DCV) hypothesis of strategic action is intended to help firms stay relevant and is of strategic advantage for larger corporates and their stakeholders.

In this chapter, we will also learn about different types of marketplaces, and how to classify these marketplaces using the niche density (number of firms in a marketplace) and carrying capacity (size of the market) approaches. It is important to recognize the link between the concept of dynamic capability and the type of marketplaces. By operating in different types of marketplaces across different business divisions or regional geographies, the firms may be able to gain experience and develop structures, processes, and behaviors to not only survive but also thrive in a VUCA world.

Exhibit 3.x illustrates the evolution of DCV, based on the refinements of RBV, KBV and CCV. KBV distinguishes capabilities (and knowledge-base of the capabilities) from resources. CCV distinguishes core competencies (creative integration and innovative combination of knowledge) from ordinary capabilities (articulation and replication of knowledge). DCV distinguishes transforming capabilities, from core competencies.

Exhibit 3.x: Refinements in RBV, KBV and CCV Bring DCV in Perspective

Entropy Mechanisms under Dynamic Environments

We need a significant revision in the original elitist assumptions of the RBV, KBV and CCV, to account for the success of firms in face of the environmental crisis and dynamism in the 21st century. RBV, KBV and CCV were all based on a linear, functional approach, emphasizing acquisition and possession of resources, knowledge and core competencies. RBV, KBV and CCV held that if elitist firms developed increasingly higher-order resources, knowledge, and core competencies through innovative combinations and creative integrations, they will be able to stay relevant with a competitive advantage on a sustainable basis. Central and common to all these three views is a strong belief in the isolating mechanism assumption – that complex resources, knowledge, and core competencies are difficult to substitute and imitate, therefore giving rise to firm heterogeneity, above-average returns and a competitive market share.

To motivate the need for the alternatives to RBV, KBV and CCV, we will use the concept of entropy. In thermodynamics, entropy is a measure of disorder or information deficit in a system; valuable knowledge declines in closed systems, reaching a point when the system lacks any usable valuable knowledge. By focusing almost exclusively on factors internal to a firm, RBV, KBV and CCV inherently imply rapid entropy or loss of valuable useful knowledge of an elitist firm in dynamic environments. In the chaotic, crisis-driven, and catastrophe-aware world of the 21st century, the limitations of these static and elitist perspectives have become evident. The ability of many emerging market firms to successfully compete with large elitist MNEs has further precipitated a need for other alternative, and more inclusive, internal firm-based perspectives on strategic advantage.

Let’s identify three major factors contributing to entropy in dynamic environments, and label them as “eroding mechanisms”. As illustrated in Exhibit 3.x, eroding mechanisms counter the isolating mechanisms, and have powerful influence on the ability of the firms to sustain their strategic advantage.

Exhibit 3.x: Entropy Counters RBV, KBV and CCV in Dynamic Environments

Non-consumer Mainstreaming: Research on innovation shows that new entrants often succeed using alternative sets of resources, knowledge and core competencies to address the needs of those presently not consuming a product, being underserved and/or overlooked. Christensen’s (1997) work Innovator’s dilemma finds most dramatic innovations occur when firms strive to design products addressing the needs of those who are not currently consuming a product. Christensen shows that in a number of industries, firms who introduced such innovations for non-consumers eventually gnawed into the advantage of firms who were focused on former consumers. Examples include the small off-road motorcycles introduced by Honda in the 1960s, Apple's first personal computer, and Intuit's QuickBooks accounting software. Though they seemed to be niche products initially, eventually they all created massive growth.

Entropy-effects of non-consumer mainstreaming have increased in the industrial markets, as firms have shifted their focus from empowering and sustaining innovations, to efficiency innovations (Christensen, 2013). The income inequity level has risen sharply worldwide, with nearly 80% of the world population – residing primarily in Africa and South and Southeast Asia – earning less than $2 / day. With increased globalization, there is an inter-firm rivalry jostling for capturing the left out 80% consumers.

Empowering innovations translates into transforming complex and costly products into simpler, cheaper, and redesigned products for a wider range of consumers. In the computer industry for example, there have been several waves of empowering innovations, which have expanded the consumer base from governments (mainframes, priced at $100,000+), to businesses (desktops), to urban consumers (laptops), and to even rural users (tablets – such as the $40 Akash tablet designed by the scientists in India and the US). Exhibit 3.x tells the story of Sony, once a pioneer in empowering innovations, who later became entrapped when even more empowering innovation became possible.

Exhibit 3.x: Sony – An Empowering Innovator Gets Entrapped

| In the 1950s, Akio Morita, the founder of Sony, launched a series of miniature products, ranging from portable players, portable radio, portable television, and portable video recording. They had resounding success each time, as the established leaders failed to notice the disruptive effects until they lost the market totally. For Sony, each new wave of miniature products offered more attractive margins, and offered the motivation to invest in miniaturization core competence and its new application. In 2000s, with the rise of internet, downloadable music became a reality. Sony had a really big CD business, and had little motivation to invest in this business. That allowed Apple’s entry and rise in the music industry, using first the iPod and then the iTunes. |

Source: Adapted from Christensen & Raynor (2003)

Sustaining innovations improve the performance of established products and services along the dimensions that customers in major markets are willing to pay a premium for. They contemporize products to be in sync with the needs, aspirations and lifestyle of today’s consumers for which they have much greater interest and willingness to pay. Examples include microprocessors enabling personal computers to operate faster; and battery enabling laptops operate longer. Overall with globalization, the number of firms pursuing sustaining innovations has increased; whereas, the ability of all firms to make meaningful sustained innovations, without undue cost increases, on a continuing basis has decreased drastically.

‘Efficiency’ innovations improve the cost-effectiveness of existing products, so that the consumers get greater value for their money with even superior quality. These are the types of innovations that many emerging market firms like Patanjali Ayurveda are following very successfully, to cater to the left out 80% market. Other examples of efficiency innovations include organizational innovations such as just-in-time manufacturing, online insurance underwriting by GEICO, and technological innovations such as the mini-steel. Exhibit 2x highlights the case of ministeel and dramatic efficiency innovations, that allowed greater mass access for cars and other steel-intensive products.

Exhibit 3.x: Ministeel as a disruptive efficiency as well as sustaining innovation

| Minimills were a major efficiency innovation in the steel industry in the mid-1960s. Minimills, that used recycled steel for making steel, enjoyed a 20 percent cost advantage over integrated mills that instead used iron ore. Ministeels initially offered low quality steel and targeted a market underserved by the integrated mills. They offered rebar - small steel bars made from scrap – to create reinforced concrete. Rebar business accounted for only 4% of the integrated mills’ tonnage, and offered a gross margin of only 7%. The integrated mills were therefore happy to exit rebar business, and focus on higher-margin steel products. As the last integrated mill exited from the rebar business, and the growth opportunities in rebar business diminished, cut-throat competition among the minimills dropped the rebar price by 20%. To sustain their profitability and growth, the ministeels had to pursue sustaining innovations, to make better-quality steel in larger shapes, such as thicker bars and rods. For the integrated steels, this market tier was twice as large as the rebar market, and offered profit margins of 12%. The ministeels invested in equipment to make the larger shapes, and improved the quality and consistency of their steel. Again, the integrated steels had to exit this market, to focus on more profitable products. As the last integrated mill exited, the price of these thicker bars and rods also collapsed. This process of moving to the next upward tier continued, until the integrated mills ran out of markets to flee to. Source: Adapted from Christensen & Raynor (2003) |

Political powerplay: Non-market factors, including governments and other social actors, play an important role in enabling competing firms to develop alternative sets of resources, knowledge, and core competencies. Let’s consider three types of political powerplays – predatory, regulatory, and reputation. At times firms experience predatory powerplay, i.e. regulators may be blindsighted by rivals who lower prices and assume losses for a temporary period in order to capture customers and vendors, away from existing firms. Conversely, regulators might impose very high taxes, liability and insurance costs, or audit and reporting requirements, thereby making an existing firm’s operations financially unviable. Finally, reputation erosion occurs as established firms become a target of reputation powerplay. Here, the consumers may choose to boycott large successful firms who are highly visible to various stakeholders and media, as they seek to push corporates to align more with their values of conscious capitalism, including green environment, human rights, and reasonable profits.

Globalization Games: We identify three types of globalization games that may erode the advantage of established firms:

Development Games – governments in emerging markets may support the development of their firms using a variety of means - e.g. they may compel foreign firms to transfer intellectual properties with limited compensation, and/or they may be lax on issues of human and environmental rights. They may also use public investments for acquiring raw materials from around the world and then offer them to their domestic firms at below market costs; and/or, they may manipulate their exchange rates if they are an export-driven economy. As a matter of fact, the Chinese government is known for aggressively pursuing all these means. Thus, when governments focus on these development efforts for specific sectors with large emerging markets, firms in other nations may suffer rapid erosion of their strategic advantage.

Trade Games –governments in industrial markets may promote industries that are capital and technology intensive as these require specialized skills, offer scope for improving productivity in their nations, and sustain well-paying jobs both in production and service offerings. They may use state-funded enterprises and defense initiatives for the initial development of the industry, offer fiscal incentives, R&D and training subsidies, and state partnership to their domestic firms. For instance, the Canadians supported aircraft development through state-run Canadair, supported Technology Partnerships Canada (a form of R&D assistance), Export Development Canada, and military contracts for maintenance and training. Similarly, many governments in Europe came together to promote and support Airbus in order to create a viable European aircraft alternative to Boeing of the USA. Boeing had to lobby hard with the US government in order to regulate and contain the European government support for airbus, and to sustain its strategic advantage.

Industry Games – in a global environment, every national region looks to offer different types of strategic advantages to the domestic firms, because of their industry base, education and skill base, innovation initiatives, and investments involving enhancement of productivity of the local workforce including places where an affordable cost of living allows labor costs to be dramatically low. Due to this, global production and service patterns are subject to rapid change; and these changing patterns in turn offer new opportunities for trade and exchange, enabling even new or less known firms to dramatically improve the cost-effectiveness, design, and value of their products over the established firms.

| In the 1990s, the PC market was mostly a corporate market (roughly 75% of volume). Corporate buyers wanted a commodity. They were buying 500 or 5000 boxes, they wanted them all the same and they wanted to be able to order 500 or 5000 more roughly the same next year. They wanted to compare 4 vendors on price with the same spec sheet. They didn’t care what they looked like (and they were going under a desk anyway) and they didn’t care how easy it was for non-technical people to set them up because the users would never touch the configuration. Nor did they care much about the user interface, because most of the users were only going to be running 1 or 2 apps anyway. That resulted in what Christensen & Raynor (2003) referred to as low-end disruption of the personal computer market – the profits of desktop manufacturers fell dramatically, and they were forced to change their business model to essentially assembly. The industry changed from being integrated into disintegrated, and the products evolved into modular architecture, that offered users freedom to customize their computer using off-the-shelf parts and software. Source: Adapted from Evans, 2013 |

The Dynamic Capability View under Dynamic Environments

With a greater understanding of the risks of entropy mechanisms, there has been a huge interest in developing new intrinsic perspectives of strategic advantage that are sensitive to environmental dynamism. One of the most important of these perspectives is the Dynamic Capability View (DCV), which is an outgrowth of the previous research on resources, knowledge, and core competencies (Teece, Pisano & Shuen, 1997). The purpose of DCV is to explain how competencies are transformed over time so as to provide innovative responses to market changes (Helfat et al, 2007), and also focus on how firms invest in, trade, and exchange their resource and knowledge base, so as to maximize organizational fit with the environment at large. The term ‘dynamic’ connotes agility, speed, and timeliness in addressing the changing external market conditions (Teece, Pisano & Shuen, 1997).

Baretto (2010: 171) offers the following definition of dynamic capability based on his synthesis of the literature: “A dynamic capability is the firm’s potential to systematically solve problems, formed by its propensity to sense opportunities and threats, to make timely and market-oriented decisions, and to change its resource base.”

We discuss below three major perspectives on DCV: the process perspective, the structural perspective, and the behavioral perspective.

The Process perspective of DCV has its origins in the scholarly work of Cyert and March (1963), who presented the sense-making process within a firm emphasizing how certain codes are more or less likely to be learnt by a firm according to whether or not they generate positive consequences under conditions of external shocks. This outcome-based sense-making process helps a firm adapt to its environment and build its adaptive capability.

A major factor in the challenge for sense-making process is the amount of disruptive change experienced in a market (Collis, 1994). Based on the amount of disruptive change, the sense making process requires different types of dynamic capabilities, as illustrated in Exhibit 3.x.

Exhibit 3.x: The Process Perspective of DCV

Classification of Dynamic Capabilities

Organizational outcomes

-Enhanced strategic advantage

First-order change and improvement (or operational) capabilities: In less dynamic environments, the pace of change is slow and the extent of change is also limited. These changes call for continuous, micro adjustments and improvements in a firm’s resources and how they are deployed (Ambrosini, Bowman & Collier, 2009).

| e2v is a waste management company that is engaged in constant improvement of their waste management and energy use. They keep tinkering with their processes and systems so that they reduce energy consumption; they work on being able to recycle more and more waste in terms of quantity e.g. tons of cardboard, and types e.g. paper, oils, and solvents. Source: Adapted from Ambrosini, Bowman & Collier, 2009 |

Second-order change and reconfiguration (or renewing) capabilities: Instead of simply seeking to improve existing resources, knowledge and core competence, they focus on evaluating whether the organization is performing the right activities (Teece, 2007). They contribute to new business development, by reconfiguring the resources, knowledge and core competencies of a firm. For instance, Virgins’ reconfiguration capabilities helped it to apply its core competence in brand value into new domains, including airlines, mobile phones, cosmetics, bridal wear, cola, railways. Sony’s reconfiguration capabilities helped it apply its core competence in miniaturization into new domains, including radio, hi-fi, computers and personal navigation.

| Founded in 1979, International Greetings (IGR) is one of the world's leading manufacturers of greetings products. Over the years, it has pursued three vehicles for reconfiguration capabilities: Product line extensions, in the form of new types of greetings card; gift wrapping, crackers, stationery and accessories. Asset leverage, in the form of the acquisition of character licenses, such as Shrek, The Simpsons, and Harry Potter. Geography extension, by moving production from UK to Eastern Europe and China, to alleviate pressures on its margins and to ensure surplus to sustain new product line extensions and asset leverage options. Source: Adapted from Ambrosini, Bowman & Collier, 2009 |

Third-order change and reconstruction (or regenerative) capabilities: This may require firms to creatively destroy their resource endowments and portfolios, reconstruct an entirely new form and to move into an entirely new market space. For instance, after the World War II, McDonald’s destroyed its earlier and successful full-service car hop restaurant, and built the fast food format. People then thought that the founder-owners of McDonald’s have gone insane, but McDonald brothers were convinced that in the post-war era, people were seeking the thrill of everything on the go. Ray Kroc, a multi-mixer salesman, became so enamored by the success of the sole McDonald restaurant in San Bernardino city, California that he decided to first license the McDonald format in 1954, and then bought the global rights on that format in 1961 for $3.7 million in cash (equivalent to $16.2 million in 2013).

Exhibit 3.x illustrates the case of GlaxoSmithKline, which embarked upon building dynamic capabilities after its industry experienced a significant crisis.

Exhibit 3.x: Reconstruction Capabilities in the Pharmaceuticals Industry

| Historically, pharma companies hired a large number of scientists, and invested a large amount in R&D trying to discover and test thousands of chemical entities for their efficacy in treating a range of illnesses. Over time, the pipeline of new chemical entities began drying up, with major pharmas restricted to the introduction of only one or two new drugs per year. The increasing costs of drugs created a crisis like environment and rising threat of intellectual piracy especially in the emerging markets that could not afford these costly drugs. That forced a series of major mergers and acquisitions and rapid consolidation of the pharma industry during the 1980s and early 1990s. Glaxosmithkline emerged after Glaxo merged with Smith Kline, who had earlier combined with Beecham. In the mid 1990s, GlaxoSmithKline acquired hundreds of much smaller biotechnology and other firms, many of whom had never sold any products, and who operated with quite different technologies and science bases. It followed up with a series of divestments, and outsourcing activities traditionally performed in-house. Source: Adapted from Ambrosini, Bowman & Collier, 2009 |

The Structural perspective of DCV emphasizes the role of social and organizational structures in guiding the knowledge management processes, especially for supporting higher-order dynamic capability (Zollo & Winter, 2002; Macher & Mowery, 2009). Social and organizational structures include technological paradigm, ecological context, and organizational design.

New technology structures may foster higher-order dynamic capability. For instance, in an interesting study, Barley (1986) demonstrated that the introduction of medical imaging devices, such as the CT scanner, challenged traditional role relations among radiologists and radiological technologists, and this changing social structure spurred changes in organizational processes, depending on the individual-level factors.

Similarly, new ecological structures, such as new space and institutions, may foster higher-order dynamic capability. For instance, open offices and competitive conditions facilitate open administration and organic interaction, while closed offices with regulated institutional conditions may perpetuate a bureaucratic logic with rigid administrative structures and processes over time (Baron et al, 1996).

Finally, organizational design (e.g. tall vs. flat, functional vs. multidivisional, matrix vs. network) also impacts the development of higher-order dynamic capability (Felin et al, 2012). For instance, a multi-divisional organization design might give rise to gaps in shared knowledge about different functional competencies across parts of the organization, and, in turn, compromise integration, innovation and change (Hoopes and Postrel, 1999). Inter-organizational structures are also important. Using data on acquisitions in the banking industry, Zollo & Singh (2004) found that the dedicated organizational structures for improving the process of codification of acquisition-specific knowledge contributed to post-acquisition performance. Similarly, using data on alliances among the US-based firms, Kale & Singh (2007) found that the dedicated organizational structures for improving the process of alliance learning contributed to firm-level alliance success.

Exhibit 3.x illustrates the structural view of DCV, and shows how it complements the process view of DCV.

Exhibit 3.x: The Structural View of DCV and its complementary with the Process View

The behavioral perspective of DCV

The concept of corporate-level dynamic capability faces the challenge of reconciling human agency (i.e. freedom of people to make choices), with the tendency of all collectivities to suffer from inertia. The human agency provides this new energy, by directly influencing the development and operation of organizational and social processes and structures. Human agency that shapes corporate-level dynamic capability may be set among all members (e.g. in fully decentralized organizations), or led by a few influential formal or informal leaders (e.g. senior executives or decision-makers).

In practice, individuals demonstrate varying degrees of agency (i.e. true freedom of choice). When the degree of agency is low, individuals may act in a passive, fast, automatic, habitual or regularized fashion. The degree of agency tends be low when the members involved have limited amount of resources, knowledge, and skills to cope with change, such as in highly turbulent situations. Thus, the behavioral perspective regarding human agency complements the process and structure perspectives on the development of dynamic capability.

Exhibit 3.x portrays two alternative models of how behavioral factors may interact with the structural and process factors of DCV and contribute to organizational outcomes. In model 1, structures guide processes to shape behaviors for effective decision-making. In model 2, behaviors shape structures, which in turn moderate how behaviors shape processes that generate organizational outcomes.

Exhibit 3.x: Behavioral Factors Interact with the Structural and Process Factors of DCV

Model 1: Structures Guide Processes to Shape Behaviors for Effective Decision Making

Model 2: Behaviors Guide Processes, moderated by Structures, for Effective Decision Making

The behavioral perspective expands the focus of DCV from the ‘doing” aspect, to the “deciding” aspect (Helfat et al, 2007: 115). This ‘deciding’ aspect is a function of cognitive, emotive, and social/ relational factors, as discussed below.

Cognitive factors and Organizational decision-making

Strategic decision-making involves cognitive factors such as planning, attention, and problem solving. Leaders seeking to promote a distributed model of strategic decision-making may shape enabling organizational processes and structures by asking questions such as: How to sensitize planning to opportunities emerging in the distant horizon? How to filter critical issues for attention? How to afford requisite support to members for their problem solving strategies?

Eesley and Roberts (2009) find that leaders and change agents who bring experiences with a broader set of responsibilities and functions allow firms to build more valuable and cognitive representations of market opportunities. However, under conditions of highly novel technology and rapidly changing industry, over-reliance on the prior experience of key executives can have negative effects (Eesley and Roberts, 2010). Under these conditions, it is important that the organizational processes and structures also support forward-looking cognitive efforts, such as envisioning novel scenarios and discovering innovative options as part of the problem-solving behaviors (Gavetti and Levinthal, 2000). But the flip side points to firms or individuals who rest on previous laurels, thereby tending to rely more on historical path-dependencies (Laamanen and Wallin, 2009); this in turn orients individuals and firms more towards reaffirming and reproducing existing resources and routines, as opposed to spurring new sets of activities for driving change. Therefore, as alluded by model 2 of behavioral factors above, corporate-wide organizational structures that trigger early warnings and sensitize members about the seriousness of the actual or impeding crisis may be helpful in breaking historical path-dependencies (Felin et. al., 2012).

Firms may also be able to design structures to guide process that in turn shape behaviors (model 1 above). Corbett & Neck (2010) identify three types of organizational attributes through which corporate executives may help shape cognitive or mental maps for the decision-making processes and enable major innovative breakthroughs. These organizational attributes are structures and processes related to

(1) the ‘arrangements’ an organization needs to make or secure to bring about changes in the organizational processes

(2) the ‘willingness’ to change current organizational practices

(3) the ‘ability’ to execute change in organizational practices.

Arrangements structures and processes include culture, coaching, and top management support. To elaborate, an entrepreneurship-supportive culture encourages experimentation and thereby accepts minimal losses. Coaching is important for members when they have limited experience with a novel technology or market. Top management support is compulsory to protect members from being a scapegoat while working on innovative efforts. Without this ‘vital’ support from the top management, innovative efforts are often found wanting, lack continuity and focus.

Willingness structures and processes address issues such as career conflicts. Research shows that many individuals are unwilling to take international postings, because of a fear that this will take them away from the top managers at their home-base and exclude them from future advancement opportunities. Under these situations, willingness structures and processes guide individuals to pursue those opportunities, and stay committed to them (Mitchell et al., 2000).

Ability structures and processes enhance the abilities and build confidence. An example of such abilities is bricolage, defined as ‘making do by applying combinations of the resources at hand to new problems and opportunities’ (Baker and Nelson, 2005: 333); that bricolage relies on scavenging various resources so as to extract usefulness from resources that others do not value or do not intend to use. Therefore, it banks on experimentation or improvisation and in doing so, breaks down or reconfigures resource combinations. Individuals and firms who target bricolage for addressing particular issues (selective bricolage) are more likely to be successful.

Corbett and Neck (2010) conclude that firms with great entrepreneurial ability tend to show a greater cognitive balance with emphasis on all three types of mental maps (arrangements, willingness and ability) and thereby enjoy better dynamic capability. In contrast, firms showing cognitive imbalance tend to experience lower dynamic capability and eventually lose out on the strategic advantage with new initiatives.

Emotive Factors and Organizational Decision-making

Strategic decision-making also involves emotive factors, i.e. moods and motives. Cognitive psychology based on neuro-scientific evidence shows that in practice, cognitions work interactively as well as conjointly with emotions in regulating thought and behavior (Duncan & Barrett, 2007). Emotions may manifest as either transient moods (e.g. fear, anger) generating temporary change in mental states, or intense motives or drives (e.g. pride, envy) generating a more sustained modification in mental states. As mood and/or motives are activated, a change in behavior is triggered; this could either be deliberate involving new strategic decisions rooted in a systematic evaluation of the stimuli; or could be ‘adhoc’, such as involving a routinized emergent choice response, based on a general sense or gut feeling about the nature of the stimuli and its potential impacts. Exhibit 3.x portrays this emotion-based organizational decision-making.

Exhibit 3.x: A model of emotion-based organizational decision-making

Emotion-based ability has generated a considerable interest among scholars of human behavior. Known also as emotional intelligence, it refers to an individual’s ability to recognize and regulate one’s emotions, so that desired decisions that are taken are in the best interests of all parties concerned (Salovey & Mayer, 1990).

Huy (2012) identifies the need for organizations to develop their own emotional capability comprising of the ability to recognize, monitor, discriminate, and attend to emotions of employees at both individual and collective levels. His organizational emotional capability theory posits that “organizations that develop procedures related to emotion management and that provide systematic training on this subject to various managers likely reduce the need to rely on the innate competence of individuals’ emotional intelligence.”

The role of emotional intelligence and organizational knowledge structures (i.e. emotional capability) in enhancing emotion-based organizational decision-making for enhanced strategic advantage, and in the process developing dynamic capability in the form of improved knowledge structures, is illustrated in Exhibit 3.x

Exhibit 3.x: A model of developing emotion-based dynamic capability

Knowledge structures

Emotional intelligence

Dynamic Capability

Examples of organizational events eliciting strong emotions among large groups include any radical change, be it in the organizational identity, change in the executive leadership team, mergers and acquisitions, strategic alliances or joint ventures, and/or outsourcing and downsizing. Different sub-groups within the organization experience different emotional responses to any such event, and may have multiple ways to deal with their emotions (Huy, 2012). For instance, when key executives leave after a hostile takeover by another company, for some it may be beneficial in terms of individual growth, while for others it may be malefic due to the individual connect that they possibly had with those employees.

Huy (2012) studied a large technology firm, where top executives emphasized structure and process perspectives of DCV. The study showed that strategy implementation faced significant group-focus emotional issues related to the social identities of the middle managers, such as newcomers vs. veterans, and English- vs. French- speaking. These group-focused emotions led middle managers to support or covertly undermine a particular strategic initiative, even when their immediate personal interests were not impacted.

Relational factors and Organizational decision-making

Finally, relational factors also play a significant role in strategic decision-making. In dynamic markets, individuals often lack the capacity and capability to enact the full range of competences necessary to make and execute effective organizational decisions. They must seek complementary resources, knowledge, and skills via their social network of relationships, both within the firm, as well as outside the firm such as consultants or alliance partners (Jones et al, 2011; Dyer & Singh, 1998).

Scholars emphasize the need for the organizations to develop their social capital, a term connoting cognitive and emotive connections (e.g. “goodwill, fellowship, sympathy among individuals and families) with key groups (Hanifan, 1920). Blomqvist & Seppänen (2003) observe that in dynamic markets, people must learn how to establish, manage, and dissolve relationships, while also maintaining a good reputation as a potential partner in the market. The capability to build trust, to collaborate and to simultaneously manage them becomes critical for effective decision-making under uncertain and crisis-laden situations. Social networks are important because friendship and kinship ties can provide access to resources at less than market price (Starr and Macmillan, 1990), or even provide resources that are simply not available via market transactions (Baker, Miner & Eesley, 2003). Networks strongly shape the trajectory of a firm because they allow people to bootstrap resources, knowledge and insights, when such assets are not available to them directly based on their own historical paths of experiences, and thus improve the dynamic capability of the firms to respond more effectively to crises or new opportunities (Jones, Macpherson & Jayawarna, 2011). An additional benefit of social relationships in the contemporary knowledge economy is its potential to generate large amount of data, referred to as “Big Data”. Companies such as Google and Facebook are essentially Big Data businesses, whose staggering market valuation and profitability steps from analyzing data about those connected to their products, and applying that to advertising.

In dynamic markets, high levels of solidarity, i.e. strong long-term exclusive relationships within a small group, can be counterproductive as well (Portes and Landolt, 1996). Burt’s (2005) research demonstrates that optimal network value is created by structural holes, i.e. by brokering connections between segments that would be otherwise unconnected. High levels of solidarity with a small group is referred to as within-group or bonding social capital, as opposed to “weak ties” for strategic and need-based exchange of resources, knowledge and insights, which are referred to as across-group or bridging social capital (Woolcock, 1998). Therefore, in dynamic markets, bridging social capital based on weak ties have been found to be more effective in giving individuals flexibility of innovative action and access to new, creative knowledge structures that are more pertinent for dealing with change.

Dynamic Capabilities and Firm Performance

Having discussed the process, structural, and behavioral perspectives on the development of dynamic capabilities, an obvious follow-up question is how dynamic capabilities are related with organizational performance outcomes. There are three schools of thought in this regard.

The first school contends a direct effect of (stronger) dynamic capabilities on performance outcomes such as competitive advantage (Teece et al., 1997; Zollo & Winter, 2002).

The second school contends an indirect effect, whereby the firm’s resource-base mediates the influence of dynamic capabilities on performance outcomes (Protogerou et al., 2011). Thus, Ambrosini, Bowman & Collier (2009) suggest a two-step process through which dynamic capabilities influence a firm’s performance. In the first step, dynamic capabilities contribute to the development of resources, knowledge and core competencies, and in the second step, these resources, knowledge and core competencies contribute to a firm’s performance.

The third school contends an interaction of both direct and indirect effect, emphasizing these direct effects represent influence on organizational decision-making (Eisenhardt & Martin, 2000; Helfat et al., 2007). Schilke (2014) used a sample of R&D alliances to show that the alliance learning (interpreted as dynamic capability) influences firm’s performance mostly indirectly, i.e. by increasing the firm’s alliance management capability (interpreted as an ordinary knowledge asset). However, the alliance learning also had a direct positive impact on firm’s performance, indicating that the dynamic capabilities also enable ad-hoc problem-solving decision-making strategies in addition to building knowledge assets (Schilke, 2014). Further, dynamic capabilities may also shape the direct influence of knowledge assets on a firm’s performance. In fact, sometimes this influence can be negative – for instance, when dynamic capabilities generate undue or disproportionate disruption in existing knowledge assets (Schilke, 2014).

The relationship between dynamic capabilities and firm performance is moderated by three major contingency factors, including market dynamics, organizational attributes, and human agency. As previously observed, market dynamics influence whether a firm’s knowledge assets generate sufficient functional energy to offset entropy pressures, and are able to assure and sustain strategic advantage. Drnevich & Kriauciunas (2011) find that market dynamism negatively impacts the contribution of ordinary knowledge assets and positively impacts the contribution of dynamic capabilities to firm performance. Similarly, organizational attributes, such as strategic intent, history, scale and scope may also influence how organizational decisions for continuity or change are translated into newknowledge assets. Baretto (2010) underlines how strategic commitment to significant future market growth might provide an impetuous to dynamic capability development. Finally, human agency or freedom may accept the processes, structures, and behaviors triggered by past developments of dynamic capability, or may reject or modify that.

Exhibit 3.x portrays the influence of the three contingency factors in the relationship between dynamic capability and firm performance. The exhibit includes not only the feedforward relationship between dynamic capabilities and firm performance, but also how firm performance generates a feedback loop, triggering executives to re-evaluate processes, structures and behaviors undergirding current dynamic capabilities. This re-evaluation process in turn triggers organizational decisions for strategic and/or adhoc developments in their knowledge assets, which include resources, knowledge, and core competencies/ insights.

Exhibit 3.x: A Contingency model of Dynamic Capability and Firm Performance

Human agency dynamics

Organizational attributes dynamics

Market dynamics

Dynamic Capability Development Trigger

Marketplace Characteristics and How to Develop Dynamic Capability

Marketplace characteristics is an important factor in the behavior of the firms. When firms operate in multiple marketplaces that have differing characteristics, that can be a powerful way to develop dynamic capability. The behavior of participants in a marketplace depends on the characteristics of the marketplace in which they operate. As shown in Exhibit 6.5, there are two typologies of market structures – one based on the niche density (i.e. the number of competitors), and the other based on carrying capacity (i.e. the industry lifecycle). In economic theory, four major types of traditional markets are identified based on the number of competitors: (1) Monopoly (single firm), (2) Oligopoly (a few firms), (3) Monopolistic competition or niche markets (many firms), and (4) Perfect competition (numerous firms). Another important structural characteristic is the industry lifecycle. In strategy literature, four types of markets are identified based on the industry lifecycle: nascent markets, hyper-competition, dominant firm, and fragmented market. Each of these market structures offers differing constraints, opportunities and incentives to the firms. Therefore, each market structure encourages distinctive types of behavioral capability, and when the firms operate across different market structures, they could develop higher-order change capabilities.

Exhibit 6.5: Typologies of Market Structures

Market Structures based on Niche Density, and Strategic Behaviors

Monopoly: Monopoly refers to a market structure with only one firm. The monopoly firm is largely free to decide its own price, output, and other product and service features. However, if the monopolist overtly restricts the output, over-prices its products, and fails to offer high quality services, then it faces a risk of new firms entering the market and trying to cater to the market segment left unsatisfied by the monopolist. Traditionally, monopolistic firms are viewed in a bad light – they tend to be complacent, bureaucratic, inefficient, not very innovative, loathsome to new entrants, and lastly keep their prices exorbitantly with poor service quality. The basic assumption on which a monopolistic firm conducts its business is that it will be able to profit from its exclusive position in the market just by preventing new competition. With the profits being huge at the onset, it induces other firms to try and replicate the same, even if other rivals exist. Historically, several large firms have been known to act in this manner, such as Microsoft using its domination in the personal computer industry in the 1990s to drive out Netscape, once a leader in the web navigation market. Alternatively, if all other rivals of a large firm are roughly equal to its size and are few in numbers, the players may seek to collude and coordinate their actions. OPEC for example – the association of the oil and petroleum exporting countries – has been known to act in this behavior striving to keep the oil prices high.

Monopolists are known to engage in a range of tactics, or games, to impede the entry and success of other entrants. One such game is “predatory pricing”, wherein the firm charges a price below its costs with the intent to drive out other entrants. Another game is “essential facility denial”, wherein the firm denies the use of essential facilities, such as refrigerated freezers given by an ice-cream company to the retail outlets, to other entrants. “Vaporware” is the third game, wherein the firm makes fake announcements intended to stop customers from switching to a better product of other entrants. Governments try to check the negative behaviors of monopolists using anti-trust and fair competition laws.

As discussed in Exhibit 6.6, in the Internet era, new types of monopolies – referred to as creative monopolies – have emerged, which are actually helping to cut the monopoly power of suppliers, and transfer value back to the consumers. A great example is Amazon, which in 2014 in the US alone held a 67% share in the e-book market, a 41% share in the new books market, and a 15% share in the total e-commerce market. Since then it has strengthened its eBook market position by introducing a highly successful eBook reader. It has used its monopoly power in the eBook market to create a business model where it asks all publishers to make the new eBooks available to the consumers for $9.99. It advocates sharing 30% of this value with itself, and the rest being split equally between the authors and the publishers. Amazon flexed its monopoly power muscles in this case as it noticed that legacy publishers are increasingly becoming like irrelevant middlemen whose presence in reality is keeping book production costs unreasonably high; therefore it offers an option to the authors to publish directly with it. On the other hand, the traditional publishers hated this approach, as it undercut their ability to sustain their profitable business models. As a counter response, many major publishers colluded with Apple to force a model on eBook sellers where the publisher sets the prices for books and retailers simply take a commission. They also tried hard lobbying with the government to introduce regulations to break Amazon’s monopoly on eBook distribution. However, in 2012, the Justice Department found the major book publishers at fault for colluding to prevent the creative entrepreneurship of Amazon.

| Exhibit 6.6. A new golden age of creative monopoly Since Google leapt ahead of Microsoft and Yahoo in internet search in the early 2000s, it has maintained a near monopoly position. In 2013, Google owned 67% of the global search market followed by Microsoft at 18% and Yahoo at 11%. Google owns less than 3% of the global advertising market and less than 0.24% of the global consumer tech market. Instead of defining itself as a search company, Google has framed itself as "just another tech company," which according to Peter Thiel, the founder of PayPal, has allowed it to sidestep scrutiny. Theil refers Google as a creative monopoly one that is “so good at what it does that no other firm can offer a close substitute.” In contrast with “illegal bullies or government favorites,” he observes, “creative monopolies give customers more choices by adding entirely new categories of abundance to the world.” Google’s motto "Don't be evil" is a characteristic of new Internet era monopolies that take ethics seriously, so that a monopoly status does not jeopardize their existence, but allows them to play a positive transformative role. It has become a monopoly by inventing something many times better than any peer product. Such creative monopolies drive progress, such as when Microsoft displaced IBM, and Apple challenged Microsoft’s decades-old operating system dominance. Being a monopoly then helps these firms focus on caring for the employees and for the society, unlike the firms who need to be focused on today’s survival that they can’t possibly plan for a long-term future. Thiel therefore claims that “monopoly is the condition of every successful business”. Many hold that the uncreative kind of monopolies is created not by markets, but by governments. In the US, government granted a monopoly status to AT&T in the late 1940s. Even though AT&T scientists made several great inventions—automatic dialing, new switchboards, executives make decisions as a monopolist decided not to use these inventions. Eventually, government had to force AT7T to license its technologies to other firms, including a device called the electronic transistor—which, in the hands of Texas Instruments, became the basis for the computer. More recently, Uber and Lyft have given choices to consumers by challenging the protection of taxis by cities. Others cite the efforts of the U.S. President Roosevelt whose government went after many big-time players like Alcoa, General Motors and the American Medical Association, in support of its efforts to revive the economy after the Great Depression of the 1930s. Source: Adapted from Foer (2014) and Theil (2014) |

Oligopoly: Oligopoly comprises of a few large firms that perceive one another as mutually inter-dependent. Success requires firms to consider the effects of their actions on the competitors’ behavior. There is an intense rivalry along several dimensions, such as price, quality, brand image, and market share. The actions of one firm influence the performance of other firms, and require counter-actions from the rivals if they wish to neutralize or balance the competitive effects on their performance. Rival firms seek to better understand the capabilities of the competitor’s along with their strategic priorities in order to better anticipate the behavior, and thereby focusing on those specific actions that would prevent detrimental responses and generating added value instead. Some actions such as upgrading the product or service quality and/or reducing the cost using technological breakthroughs that yield first-mover advantage are difficult to replicate quickly and cost-effectively – unless firms anticipate and plan for the actions of their rivals. Therefore, competitive games in an oligopoly become highly interactive.

According to Porter (1985) a firm in an oligopoly often faces a dilemma. It can pursue the interests of the industry as a whole and avoid price based competition, or it can behave in its own self-interest at the risk of sparking retaliation and escalating industry competition to a battle. Thereby, it is best for a firm to strike a balance between industry level cooperation (to avoid profit eroding warfare) and firm level competition (to avoid giving up potential revenues and profits). One way for the firms to do so is to merge with or acquire their rivals. In fact, Lynn (2011) mentions in his book, “Cornered,” showing the rising concentration and consolidation of nearly every American industry since the 1980s. Dominance by two or three firms “is not the exception in the United States, but increasingly the rule.” For example, while drugstores seem to offer unlimited choices in toothpaste, just two firms, Procter & Gamble and Colgate-Palmolive, control more than eighty per cent of the market share. Six movie studios receive almost 87% of American film revenues. Four wireless providers (AT&T Mobility, Verizon Wireless, T-Mobile, Sprint Nextel) control about 89% of the cellular telephone service market. In many industries, all the oligopoly firms collectively engage in the practice of “parallel exclusion,” i.e. efforts to keep out new entrants. In the 1980s and 1990s, established airlines like American and United kept the startup rivals out through their collective control of the landing ‘slots’ at major airports. Until they were stopped by the antitrust rules, Visa and MasterCard created parallel exclusionary policies trying to prevent the new entrant American Express from succeeding in the credit-card industry, including blacklisting banks that sought to deal with American Express.

Others hold that oligopolistic markets may encourage fierce competition among firms, allowing consumers to benefit from low prices and high production. The carbonated soft drink industry, for instance, has long been dominated by two giants - Coca-Cola since 1886 and Pepsi Cola since 1899. They sell cola drinks with similar taste and color, and controlled 70% of the market in 2012 – with Coke at 42% and Pepsi at 28% (Walston, 2014). Both have the most advanced technology for lower costs and have well-managed distribution channels, suppliers and bottlers. They exclude new entrants by keeping prices low, so that the entry is not profitable for the new entrants. They consider the reaction of each other closely, and when one reduces its price, the other follows to avoid customers switching. Knowing that the other will match price-based competition, they strive to compete on factors other than price. They invest in extensive advertising to differentiate on positioning: Coke represents happiness and moments of joy, while it protects culture and maintains the status quo. Pepsi is associated with capturing the excitement of life now, for youth who are energetic, fun loving and daring. Both firms also invest in research and development to advance their competitive advantage. Coke has about 500 brands, including Coke, Diet Coke, Fanta, Sprite, Dasani, and Powerade. Although it leads Pepsi in most market segments, Pepsi has been quite successful in developing new segments.

Overall new evidence suggests that most oligopolistic markets tend to become ineffective, and ripe for creative destruction by new firms. This is elaborated in Exhibit 6.7.

| Exhibit 6.7 The Malaise of Oligopolies The 2014 Nobel Prize winner for Economics, Jean Tirole, has conducted an extensive research on market power and regulation of oligopolies. He studied the break-up of state monopolies in various industries such as railways, telecom, and healthcare, into a small group of large firms – i.e. oligopolies. He found that these private oligopolies colluded to set prices, quantity and quality of goods, so that the privatization did not yield anticipated benefits for the society. They engaged in overinvestment to preempt entry of new firms, because overinvestment allowed them to increase supply and lower price to drive out new firms. The regulators had insufficient information about cost structures and production function of individual firms. He showed that the regulators who tried to force oligopolists to lower prices and to accept lower margins on public contracts created negative incentives for investing in cost-reducing innovations. Economic progress in several emerging markets is constrained because of the presence of oligopolistic entities. In Pakistan, after its founding in 1947, a cartel of 20 families – referred to as Bees Gharanay – controlled markets and prices. While many new families have joined this cartel since then, a small group of very influential entities continue to exert oligopolistic control over the nation’s agro-industrial production and commercial/ retail estate business. They all collude to set prices, deprive innovations, and create barriers to market entry. Consumer prices in Pakistan are about 12 percent higher than in India, and restaurants are 40 percent more expensive. Overall, the local purchasing power in Pakistan is 48 percent lower than in India. In July 2014, a McDonald’s burger in Pakistan cost US$3.04, 74 per cent more expensive than in India (Haider, 2014). Similarly, progress in several industries has been found to stall when they are taken over by a few oligopoly firms. Toporowski (2014) for instance reflects on the state of the media industry in the US: “The media has become an oligopoly. From movies to television to newspapers, a few companies own most outlets. There is less competition because there is less to choose. A person who reads The Wall Street Journal and watches Fox News can say that he is a well-versed person who understands both sides of an issue. But, Rupert Murdoch owns both outlets, and both outlets are known to host mainly right-wing conservative editorialists. Comcast owns not only NBC, which airs NBC Nightly News, but also AT&T, MSNBC and Time Warner Cable.” New technology and globalization is allowing new firms to challenge the lucrative oligopolies. For instance, many players –Apple, Google, Microsoft, Netflix, HBO, Hulu, CBS and Amazon — are entering the online media space. Online media is fast becoming a powerful substitute for traditional media, and is destroying the profits of cable, satellite and telco distributors. |

Niche Markets: consist of market segments within the larger marketplace that emphasize a particular need, or geographic, demographic or product segment but that differ along some key dimensions from other market segments in the marketplace (Teplensky et al., 1993). Nichemanship is a method of carving out a small part of the market whose needs are not fulfilled, and matching these unique needs by specializing along market, customer, product, or marketing mix lines (Shani and Chalasani, 1992). This allows each competing firm to dominate their market niche; therefore such market structures are also referred to as “monopolistic competition.” For instance, in the food market, there are several alternative niche markets, such as organics, local products, heritage varieties, biodynamics, and humanely treated livestock. To develop and sustain competitive advantage in its niche market segment, each firm invests into co-specialized set of complementary assets, including brand name, human capital, vendor relationships, and organizational culture. These assets allow firms to take actions that do not materially affect competing firms, thereby mitigating the risks of customers switching to the firms in other segments. Niche markets require firms to support their niches through continuous value differentiation. Repeated, targeted actions allow the firms to stretch their core competencies to enter into the niches occupied by their rivals. Similarly, shifts in technology and demand open opportunities in new niches. For instance, the organic food market niche is sub-divided into two niches: one where customers purchase organic food for environmental reasons and the other where customers purchase organic food for nutritional reasons.

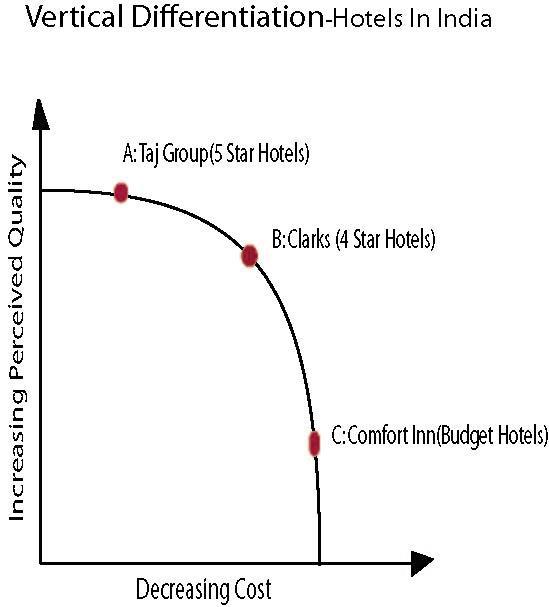

Firms have two options for value differentiation in niche markets. The first option, ‘vertical differentiation’, involves adding high performance or quality features to the complementary assets. As shown in Exhibit 6.8, vertical differentiation strategies can be displayed using a cost quality frontier. In the Indian hotel market for example, the Taj Group – a five star hotel chain – is perceived by everybody to be higher in quality and has a higher cost structure. In contrast, Comfort Inn is a budget hotel, and is perceived by everybody to be lower in quality and has thereby a lower cost structure; whereas, Clark Hotels lies somewhere in between as a budget option.

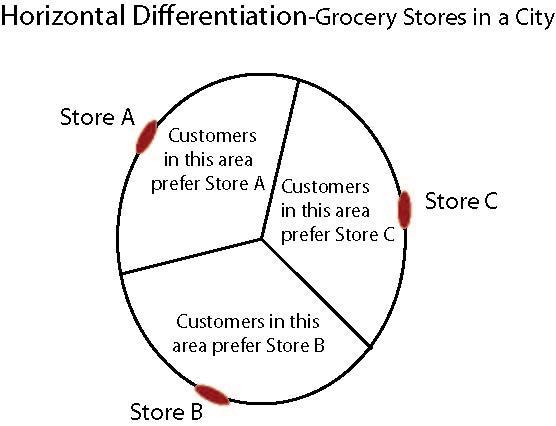

The second option, ‘horizontal differentiation’, involves creating a distinctive niche by discovering a unique way of combining and applying a common set of complementary assets, and/or by appealing to a distinct customer group. As shown in Exhibit 6.8, horizontal differentiation strategies can be displayed using a circular mapping. Consider a city that has three equally well-stocked grocery stores. The consumers tend to prefer the one that is closest to their home, and thus consumers vary in their preferences about the grocery store.

Exhibit 6.8 Horizontally and Vertically Differentiated Niche Markets

|

|

|

From a strategy perspective, niche markets are attractive when they have the following characteristics (Cuthbert, 2011: 4):

The niche is of sufficient size and has the purchasing power to be profitable.

The niche has growth potential.

The competitors have put low priority or attention to that niche.

The firm has the required skills and resources to exploit the niche.

The customers in the niche have a distinct set of needs.

The customers prefer the firm that best satisfies their needs.

The firm gains certain economies through specialization.

The firm is able to defend its niche by constructing some barriers to entry.

Consider the case of Household Insecticides sector in India, in Exhibit 6.9. Godrej has identified several niches in this Household Insecticide market, to capture an overall 50% share across categories during the 2000s:

| Exhibit 6.9 Godrej in India’s Household Insecticide Industry The Household Insecticide industry of India in early 2000s was about Rs. 10 billion (~$225 million). It was a market with huge potential, attracting a large number of multinationals and local firms. While 95% of households in India had an insect problem, only 18% of rural households and 80% of urban households used insecticides. Most of the players in the sector sourced products from the smaller local firms to gain cost efficiencies and to be able to expand market further into the rural areas through alliances with the rapidly growing organized retail sector. The oldest player in the market was Balsara Hygiene, who introduced Odomos brand in early 1960s as a personal application cream for protection against the mosquitoes, but did not expand its early franchise much. In 1984, Godrej launched household insecticide in a new “electrical mat” category with its brand Goodknight. Godrej became world’s largest producer of household insecticide electrical mats, which by early 2000s constitute 40% of the Indian household insecticide market, and captured 70% share of the mat category. In 1980s, Bombay Chemicals entered the market with “tortoise” brand by inventing the “coil” category, which constituted 25% of the Indian household insecticide market by the early 2000s. However, Bombay Chemicals was slow to seize the opportunities offered by the liberalization of Indian economy. In 1994, the British MNC, Reckitt & Colman, wrested the initiative, and became the leader in coil category with its Mortein brand. Godrej also saw the opportunity; it extended the Goodknight brand into the coil category, which displaced Mortein brand to gain leadership in the coils with a 34% market share by late 2000. Similarly, Karamchand Appliances pioneered the “electrical vaporizer” category with its All-Out brand, gaining 70% share of the fastest growing segment of the market; however, Godrej extended Goodknight into the vaporizer category also, gaining a 25% share. In 1992, Godrej entered the “aerosol spray” category with a new brand “Hit”, gaining around 25% share. It also sought to enter into the stagnant personal application category, based on a new “gel” form developed through internal R&D. These niche strategies allowed the household insecticide market to grow rapidly, reaching about Rs. 40 billion by 2013. Godrej decided to sustain its growth by going global. In 2010, it acquired the Indonesia based Megasari group, a leader in household insecticides, air fresheners and baby care. Indonesia now contributes 40% to its household insecticides global sales. It has plans to grow to other emerging markets in Asia, Africa and Latin America, and to succeed by offering value products to middle and low-income customers. Adapted from Equitymaster (2000) and Chatterjee (2002) |

A key success factor in the niche markets is the establishment of close relationships with customers. An effective strategy is usually based on the principles of differentiation and customer service. Niche markets offer an opportunity to firms having limited resources to establish a more stable long term market position through relationship marketing, and the development and maintenance of barriers to entry through product, organizational and market innovations. Parrish (2003), studying large firms in the textile business, found that these firms developed niche domestic markets as a means of competing against multinational lower cost producers. Exhibit 6.10 illustrates the strategies for identifying opportunities and competing in a niche market.

| Exhibit 6.10 Thinking Niche Markets Niche markets are excellent platforms for startups to launch their business successfully, and to grow into major players in a larger market. They defy the logic that the probability of success is directly correlated with the size of a target market. They have been the basis for the rise of several niche players, some of who have gone to become household names. To succeed in niche markets, firms need a deep understanding of their customers and their customers' needs and the ability to stay engaged with those customers. They also need to consistently produce quality, innovative products and possess a genuine regard for the well-being of their employees. They need to focus on meeting the needs of a smaller group of customers without compromising their chance to increase the appeal to a broader market. Household iron and luxury resorts are examples of niche markets. Household iron is a commodity product that generally retails for less than $30. Since 1990, Switzerland-based Laurastar has approached the household iron industry as a niche market, and targeted a specific niche where irons can be priced from $900 to $2,500. This is a niche of customers interested in pressing their clothing professionally at home. Over a period of two decades, from 1990-2009, it sold more than 2 million ultra high-end irons to households in 40 countries. It has responded to competition by hiring a team of high-caliber engineers to create the world's smartest iron. Its new home pressing system is lighter, easy to handle and features sensors which produce steam automatically as the iron is pushed forward and stops immediately as the iron is halted or moved backward. An active board assists with pressing the garment as soon as the iron moves, thereby reducing ironing time and effort by half and saving energy. Further, it has sustained its growth by deciding to become global, after its reached 25% penetration in Switzerland. Luxury resorts are a premium product that generally caters to sophisticated, wealthier travelers. Aman Resorts has approached the luxury resort industry as a niche market, by thinking small, intimate, and involving. Each of its resorts in Asia, Europe and the Americas are quite different in location, look, mood and guest experience. Yet they share the value of environmentally friendly and aesthetically pleasing. They are all romantic places in beautiful envrions, to offer a contemporary lifestyle experience of the world around that excites, shapes and nourishes. The strategy is anchored around its staff - chambermaids, drivers, cooks, cleaners, gardeners and guides – who perform invaluable small roles, pleasing the customers and offering cultural authenticity in faraway places. Instead of the over-the-top pretentions associated with other luxury brands (think marble reception areas), it favors small, distinct establishments that are designed to be in harmony with their surroundings and the prevailing local architecture. Source: Adapted from Bellisario (2009). |

Perfect Competition: is characterized by the lack of significant fixed costs or investments, and running business largely on variable costs. Firms tightly monitor their variable costs, and compete on efficiency. A most efficient use of the resources – in particular the labor and effort of the entrepreneur implies that the firms that use their labor less productively are forced to exit the competitive game. The firms do not invest in developing new technologies in-house or in expensive outside technologies – instead they rely on affordable and accessible technology. This allows newer firms to enter and survive, with limited barriers to entry. A perfectly competitive industry is analogous to a fish market near a fishpond open for public fishing, where any person may catch and sell fish. With free entry, new firms find it easy to set up shop and start producing and selling. These firms also have the flexibility to shut shop at any time without making any losses. This often invites fly-by-night players to make a fast, extra buck by free riding on the public goods and social infrastructure. Such predatory economic conditions often challenge the ethics and the sense of social and ecological responsibility of the players. Though the basic economic theory considers perfect competition to be the ideal state for social welfare, it does not provide effective conditions for the growth of the firms or the industry. Exhibit 6.11 illustrates the challenge of a perfectly competitive market, and the need for regulating this market to ensure at least some level of commitment from the firms to build trust and success.

| Exhibit 6.11 Perfect competition in India’s capital markets In the 1990s, as the government of India embarked on liberalization and globalization, India’s capital market rapidly became more perfectly competitive. It became easy for all the firms to raise capital, and the differences in reputation based purely on accumulated family wealth became less salient. This perfectly competitive market also encouraged fly-by-night operators to access the capital market for making a fast buck for themselves, and then purposefully declaring bankruptcy to avoid all obligations for repayments of principal or interest and dividend. Consequently, the sentiment of the primary suppliers of capital was seriously hurt. In order "to keep fly-by-night operators at bay," the government had to introduce appropriate measures. It barred willful defaulters from making debt issues and introduced the concept of `net tangible asset' to ascertain a "minimum tangible existence of the company seeking to access the capital market". Source: The Hindu Business Line (2003) |

The costs of government regulation must eventually be borne by each of the players. Post the Enron corporate scandal for instance, the US government imposed several stringent regulations on financial and accounting firms in the US, which severely limited their flexibility to service the competitive needs of clients, and had added to their costs of due diligence and monitoring the transactions.

The utility of the perfect competition market is greater as a standard for promoting healthy competition. A major insight from this concept is that when the access to infrastructure, technology and knowledge is based on the pay per use model, then more firms are likely to enter the market with limited risks of huge losses if they fail. Such pay per use model can bring about several creative endeavors and promote innovation and growth. eBay and Amazon marketplaces are one of the closest examples of perfectly competitive markets. They allow any seller to offer their product without investing significantly in the fixed costs of technology or inventory. Yet, for success and growth on these marketplaces, individual sellers need to build a history of positive reviews, trust and reputation, which in turn enables them to charge a premium and have an edge as compared to their rivals that lack such history.

Market Structures based on Industry lifecycle and Strategic Behaviors

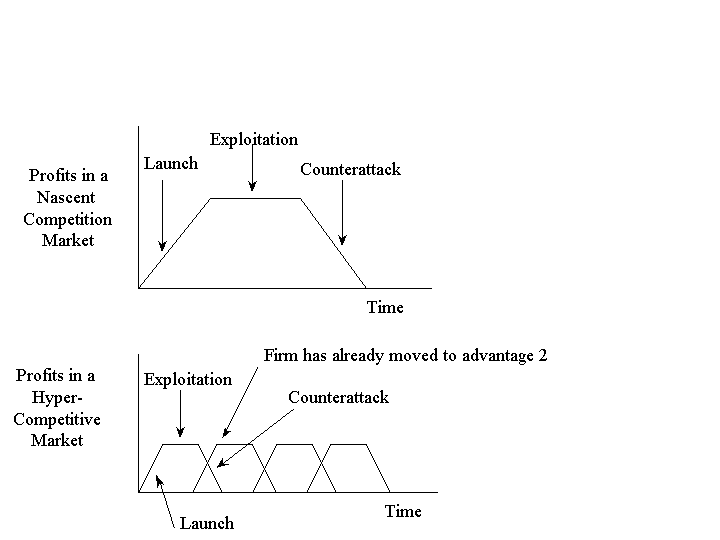

Based on the carrying capacity or industry lifecycle, market structures may be classified as nascent (emerging cycle), hypercompetitive (growth cycle), dominant (maturity cycle), and fragmented (decline cycle).

Nascent Competition Market: are usually spurred by technological innovation, newly emerging customer needs, along with economic and sociological shifts. A distinguishing characteristic of the nascent competition market is the lack of any “rules of the game.” These markets are characterized by a competitive race among the firms to establish their own technologies, and to create a dominant market paradigm centered at the use of their technologies by all the players. The firms tend to make huge upfront investments for rapidly commercializing their technologies. It is however, difficult for most firms to make profits as technological, operational and other logistics are not fully functional. This in turn jeopardizes the entire cycle involving, vendors, stakeholders, customers and investors alike. Thus, for a new entrant tasting success would mandate it to right on top on several fronts: improved technology, forging advantageous relationships with channel partners, acquiring a core group of loyal customers, accessing patient venture capitalists and entrepreneurial human capital A firm first to introduce a commercial technology, gains a lead, and might develop a “first mover advantage”. However, a failure to cement the early lead may cede the window of opportunity to the competitors. Exhibit 6.12 illustrates the vast opportunities for the nascent commercial drone industry, made possible because of rapid advancements in technology and reduction in component costs.

| Exhibit 6.12 Unmanned Aircrafts On a Commercial Flight Drones are the unmanned aircrafts. The nascent lightweight commercial drone industry is poised to transform industries from exploration and farming to film and photography and even online retailing. AeroVironment in the US has been a leader in the small military drones, and is gearing up for first-mover advantage in the commercial arena. It won an agreement with BP to offer its military drone Puma AE to conduct day-to-day operations like 3-D mapping of oil reserves in Alaska’s harsh environment, in order to improve safety and efficiency. Puma AE has a relatively long range, and was designed for surveillance. Conoco Phillips oil company has also flown two kinds of unmanned aircraft in unpopulated areas of Alaska and over the Arctic Ocean. Aviation leaders like Lockheed Martin and Northrop Grumman are watching the nascent drone market. Boeing even acquired drone maker Insitu for $400 million in 2008, but decided to focus on making larger drones with law enforcement and search and rescue applications. The development in the commercial drone industry is driven by the rapid improvements in sensor technology, and the pressures from excited potential clients. The cost of the components, technologies as well as the platforms that drones run on is dropping dramatically to make development of commercial drones feasible. In September 2014, the US government gave permits to seven movie and television production companies to fly drones, yielding to the multi-year lobbying by these companies. The government is still trying to spell out what is legal and what is not. For use by the film studies, the US government has mandated that the unmanned aircraft be used only on closed sets and be operated by a three-person team, including a trained drone operator. Globally, several experiments are underway for using commercial drones. The oldest commercial use was by Japan’s Yamaha Motor Company. Its radio-controlled helicopter drones weighing 140 pounds have been used since 1990s to more precisely apply fertilizers and pesticides. Flying closer to the ground, their spray is able to reach the underside of leaves. In 2010, these drones were introduced in South Korea, and in 2013, in Australia. In Australia, television networks have started using drones to cover cricket matches. Zookal, a Sydney company that rents textbooks to college students, began delivering books via drones in 2014. The United Arab Emirates is working to deliver government documents like driver's licenses, identity cards and permits using small drones. The British energy companies are using drones to check the undersides of oil platforms for corrosion and repairs. British real estate agents are using them to shoot videos of pricey properties. As a public relations stunt, a Domino's Pizza franchise in the U.K. posted a YouTube video of a "DomiCopter" drone flying over fields, trees and homes to deliver two pizzas in June 2013. In the US, Amazon and Google want to use drones to deliver packages. In 2014, the California-based Matternet began selling a package of one drone and two landing pads to government and aid organizations. It sees tremendous potential of drones in emerging markets with limited infrastructure, to deliver medicines and other critical, small packaged goods, and to bring blood samples bound for labs on return. It also believes that urban drones will replace truck deliveries of single express packages. Germany's express delivery company Deutsche Post DHL is testing a "Paketkopter" drone to deliver small, urgently needed goods in hard-to-reach places. Facebook is looking to acquire Titan Aerospace, a maker of solar-powered drone-like satellites, to provide Internet access to remote parts of the world. Because of all this, the drone industry is expected to reach about $89 billion in 2020s, and commercial drones are expected to capture 12 percent share of that. Source: Adapted from Lowy (2014) |