HHS 201 Introduction to Human Services Wk5

Chapter 12 Program Planning

A human service worker who was conducting a workshop on planning for several managers of group care facilities started the day with this anecdote:

Years ago when I worked with after-school groups at a recreation center, I was cornered in the game room by an eight-year-old boy insisting that I try to guess the answer to his favorite riddle. Knowing when retreat was impossible, I graciously yielded.

“What is the most important fish in the ocean?” he asked me. After a few feeble guesses, I gave up. With a triumphant grin he announced, “The most important fish in the ocean is the porpoise, because no one goes anywhere without one!”

Out of the mouths of babes come words of wisdom! This silly riddle has stuck with me all these years because it is true for most things, and especially for the planning process. It gives us a good rule of thumb with which to begin this chapter. The human service interventions we plan and implement—all our words and actions—must have behind them a clear purpose. Planning is the process that helps us accomplish these purposes in a rational way. It is a systematic method of thinking through our words and actions so that they move clients and workers along in the direction of their goals.

Planning is an activity that is already very much a part of our daily lives. Think back to the last time you moved into a new apartment, looked for a summer job, or hosted a party. Before you started packing books into cartons or sending out resumes or invitations, chances are you had already decided on a plan of action. You might not have written down a step-by-step plan, but you must have had some overall map in your mind that would take you from point A to point B.

You probably gave some thought to which of the tasks needed to be done right away and which could be put off until later. You estimated how much time each task would take and figured out whom you could ask for help. If you are a good instinctive planner, you probably thought about what you would do if the apartment did not have enough closet space, if the job you were offered did not pay enough, or if the guest of honor could not make it to your party on the date you had chosen.

Without consciously realizing it, you probably evaluated your planning process after your goal was reached. Once you had settled into the apartment, you might have looked around your living room and said, “What a mistake I made stripping the floors before I painted the walls,” “I should have checked with the neighbors before I moved in; then I’d have known that this landlord really scrimps on the heat,” or “Next time I move into a new apartment, I’m going to start packing boxes two weeks in advance rather than leave everything to the night before.”

When urged to think back over a major planning endeavor in our lives, most of us will confess we have made some monumental blunders.

I can remember at least one hot summer day when, after reminding myself over and over again to fill up the gas tank, I realized I had neglected to do it when I stalled on a lonely highway miles from the nearest garage.

or

I designed and printed a great advertisement for the big concert of the year. Then I stuffed and sealed 600 envelopes and brought them to the post office. On the way home, I showed one to a friend. He noticed immediately that I’d left the date off my fancy flyer. What a disaster!

At a party it may sound winsome to say, “Oh, I never can remember anyone’s name!” But a human service worker cannot afford to forget. Behind each name left off a list stands a flesh-and-blood child left alone on a street corner, waiting for a bus that will never arrive to take him or her to an after-school program. Behind each forgotten name is a parent stung by your apparent indifference when you are not sure just which boy is her son Joshua, even though he has been coming to your recreation group for two weeks.

It is hard to imagine a human service job that does not require problem-solving skills and systematic planning. In his book on management in social agencies, Robert Weinbach (2002) asserts that even caseworkers, therapists, or social workers who spend most of their day in direct services still will be required to spend some time on management functions. Central to all those management functions is the skill of planning. He goes on to say that it is not true that managers manage, supervisors supervise, and caseworkers should be left alone to see clients. It is not “us” versus “them.”

problem-solving skills

Systematic techniques that aid in achieving a goal in the most efficient and effective manner.

Even in an agency that uses the one-on-one, direct-service model, a worker might be assigned to:

Compile a list of agencies that assist people with AIDS

Design an outreach campaign to recruit volunteers

Help clients put on a holiday celebration

Assist clients who are starting a support group for eating disorders

Organize an open house

Plan a staff retreat

Prepare a public information campaign

Set up a child care corner in the waiting room

Gather data to be used in an application for a grant to buy new computers

Although planning is a common act of daily life, a human service worker does it in a more disciplined fashion than the ordinary citizen is likely to. In this chapter we will start by describing the basic tools and attitudes of the program design process. Then we will describe some of its models, which can be adapted for use in an infinite number of situations.

program design

The thoughtful mapping out of a program so that it includes an analysis of tasks, strategies, resources, responsibilities, schedules, a budget, and an evaluation plan.

12.1 Basic Tools of the Planning Process

No plumber or carpenter would go to a job without a bag of tools. Program planners also have their essential tools of the trade. The major ones are:

Pencil and paper

Computer, scanner, photocopier, e-mail, and planning software

Directories, schedules, and other resource materials

Calendar or memo book and a clock

Large sheets of newsprint, a chalkboard, or an erasable board.

Pencil, Paper, and a Computer

Proposing that traditional writing instruments are the basic tools of the planning process seems like a very simplistic statement. Yet, surprisingly, many people do not approach planning tasks with these in hand. Lakien (1989), an organization development specialist, asserts that systematic planning is an act of writing, not simply one of thinking. We heartily concur.

When engrossed in planning an event, we think about it almost constantly. Before falling asleep at night or when waiting at a bus stop, the mind races, buzzing with details. But although our thoughts may be profound, they are often fleeting insights, half-forgotten when we wake up the next morning. Details of plans that are not committed to paper (or to a computer with a backup disc) and later double-checked for accuracy have a way of drifting out of our grasp. One supervisor we know lamented,

When I supervised graduate community organization students in a large public agency, I lost count of the number of times I had to stop a staff meeting in the middle of a sentence to point out that I was the only one in the group taking notes on the decisions we had just made. Knowing they lacked their own personal record of what happened at the meeting, I found myself constantly calling them during the week to make sure they remembered the details of the task they had been assigned.

In the course of our busy lives we cannot depend simply on our memories. Our heads are filled with the conflicting demands of home, school, and job. A worker who is careless about the details of tasks, names, times, dates, locations, or costs often fails to accomplish the overall goal of the helping encounter despite other excellent skills.

When conducting a meeting, even the most enthusiastic beginner can forget to circulate a lined pad or have a lap top computer at the ready, with the words: NAME, ADDRESS, PHONE NUMBER (work, home, and cell), E-MAIL, and FAX NUMBER written across the top of the page. Lacking an accurate list of who attended the meeting and where those people live or work, the organizer cannot send everyone the minutes of that meeting or the notice of the next event. Without accurate records, it can take several days of diligent detective work to track down the person at the meeting who volunteered to print the flyers or staff the food booth for the neighborhood fair. All the people who do not receive the next mailing or phone call confirming their assignment are left to wonder why they were neglected. A minor omission can snowball into a major problem.

Pencil, paper, and a computer actually accomplish much more than simply guaranteeing that we remember important names, addresses, or commitments; they are also analytical tools. By forcing ourselves to write out hunches about our problems and our proposed solutions, we visualize the planning process as it might unfold. Each time we write a list of tasks that must be done, the amount of time each should take, who will do what, and what help they will need, we fill in more details in the road map of our journey to a goal. Although the shortest distance between two points is a straight line, we often need to construct a visual image to see exactly where the straight line lies. The sorting and listing process also gives us some level of predictability, alerting us to potential roadblocks we might encounter along the way.

It is a good practice to keep a small notebook (or computerized organizer) in your pocket, purse, or knapsack. Into it you can list fleeting ideas that occur to you at unexpected times, and each time someone hands you a business card or tells you his or her phone number, you have a ready receptacle for it.

Computer, Internet, and Planning Software

Although some of us still rely on the old-fashioned pen and pencil to help us remember bright ideas, commitments, and bits of information we have collected as we go about our work, computers, Internet, and several types of planning software are also becoming vital tools in the planning process. In fact, it is difficult to remember how we managed to go about our jobs before these modern aids became widely available.

The computer should be the trusty repository for the jottings you made in your pocket notebook when the machine was not available. If notes are transferred at the end of each day to your computer, placed in the proper file folder on the hard drive, and, of course, backed up on discs, they guard against the loss of the notes you have taken. They also change your scribblings into solid bits of data that can be used now or in a future project and easily shared with other planners.

We do not need highly sophisticated computer equipment to order our notes into logical categories and help us build a database of people, agencies, suppliers, and so forth. Even in the most resource-poor agency or group, at least one person is bound to have access to a computer, if not in his or her home, then perhaps at a workplace or public library. In many towns, there are stores that sell time on a computer, and most public libraries have computers that can be used by local people.

Later in the chapter we will describe several charts that assist us in moving through each step of the planning process. These charts are also available on several software programs.

When available, e-mail and the Internet are invaluable tools for networking with others who are working in similar areas of the human services to generate ideas, secure resources, and build support. Through the Internet we can cast our net wide, bringing in ideas from diverse communities. E-mail (and the fax machine as well) is a marvelous tool for keeping members in touch with the progress of each piece of the plan and for sending out a request for assistance when a planner has hit a roadblock.

Directories, Schedules, and Other Resource Materials

The telephone book for your town and specialized directories of services and brochures are the planner’s trusty companions. In the words of the advertising department of the phone company:

Let your fingers do the walking!

Perhaps you are working with a group of teenagers at a mental health center. They are trying to decide whether to go on a camping trip or to a country music concert in the next town. You suspect that both activities are too expensive. Before they get too deep into planning the details of either outing, you suggest they pick up the phone (or go to an appropriate website) and obtain answers to some key questions:

How much will each of the activities cost?

Are camping sites or tickets available?

How can they get there?

How long will it take to get there?

Armed with facts rather than speculations, they can then go on to discuss whether they will be able to obtain the time, money, transportation, and permissions they will need. Then you can help them weigh the trade-offs of each option—what they might have to give up in order to get something they want.

One worker described how she used this technique of matching facts with wishes with a group of teenagers she worked with on a summer work camp:

Several years ago I took a group of twenty older teenagers to Mexico on an eight-week work project. The members were very mature but they often pushed against the limits of their independence and my sense of caution. During the first few weeks several of them made requests that frankly overwhelmed me. “We’ve been invited to a wedding next weekend three towns away. Please can’t we go? Some people have asked us to join them in an expedition to climb a mountain. Is that okay?” Although many of their requests seemed risky, I didn’t want to arbitrarily say “no.” After a while we arrived at a program planning technique that worked wonderfully for the rest of the trip. At a group meeting we hammered out a set of basic questions: how, what, where, when, and what if? They were not to come to me with a request until they had the facts to back up their answers to those questions.

If, for example, they planned to travel by bus, I wanted to know the exact schedule and the exact cost, where it left from, and how they would get there. Many grandiose schemes were quickly put to rest after a call to the bus station made it clear that in this country you simply couldn’t get from point A to point B in two days on a shoestring budget. By the time a request actually came to me, it was quite feasible and I was likely to agree to it.

Another worker reported using this same kind of reality-testing technique with a much younger age group:

When I ran a day camp in an inner-city housing project, the telephone was my best friend. On cold and rainy mornings the littlest children would crowd around me begging to go swimming even though I knew it probably wasn’t going to be warm enough. Finally, one of the camp counselors taught her group members the phone number for the local weather report and how to look up the weather on the office computer. If WE6-1212 or checking the computer screen—said it was above 70 degrees and it wasn’t going to rain, they went swimming. If it was going to rain and was below 60 degrees, we went to a movie, to the bowling alley, or planned an indoor crafts activity. It wasn’t me making the decision. It was the objective fact of the weather forecast.

In each of these experiences, clients practiced systematic problem-solving skills that helped them to formulate current plans and equipped them to plan in the future. If the worker had access to the Internet, this would be a wonderful opportunity to show the children a practical way in which information retrieval can be done easily and used wisely. Yaffe and Gotthuffer, in their book Quick Guide to the Internet for Social Work (2000), describe a multitude of ways in which the Internet can help us in every intervention we make.

Calendar/Memo Book and Clock

Watch a group of human service workers at a case conference trying to arrange a date for their next meeting. All of them will dig into a briefcase, handbag, or back pocket and produce a well-thumbed appointment book or PDA. In it will be listed daily meetings and all the details surrounding them: who is to be seen, where the encounter will take place, and any driving or public transportation directions needed. Human service workers often list the home and work phone numbers of the people with whom they have made appointments. Then if they must cancel a meeting because of an emergency, even from home at 6:00 a.m., they are prepared (another opportunity to demonstrate our caring for clients and colleagues!).

A calendar book right at hand also helps a worker visualize what needs to be done, define priorities, and fit them in. Thus, “Stop by and see me sometime about those new regulations” and “We’ll have to get together and talk about the Kramer child some day soon” become definite half hours on a specific day. If a worker cannot make an appointment with the foster parent who mentioned she was having a hard time with the Medicaid office, a note in the calendar book is a reminder to phone her the next day and arrange a time to talk.

Most human service encounters require some type of follow-up activity. The calendar book is a logical place to list the many small tasks that will need to be done before the next interview with a client or before a deadline expires on an application for an entitlement.

Finally, a calendar book can be a device to set self-limits, guarding against burnout. It should help workers to space out their tasks at realistic intervals, with times in between for reflection or paperwork.

A watch or an unobtrusive desk clock can also help set a realistic pace. Although sensitive workers do not mechanically follow arbitrary time limits, they rarely have the luxury of unlimited time. Other clients are waiting for them, groups must begin on time, forms have to be submitted by deadline dates, or clients must be reminded to get to their jobs or interviews on time. Because every method of intervention has its own rhythm and flow, we need to establish and confirm with the clock an adequate time for a beginning, middle, and end to each encounter. Endings of meetings and interviews often sneak up on us, robbing us of the time we need to decide on subsequent steps, evaluate, or wind down emotionally. Setting a comfortable pace for our interventions is both an art and a skill.

Large Sheets of Newsprint, a Chalkboard, and Markers

To prod our memories or map out our ideas about a project, a pocket or desk pad or computer will do quite well. But when we are planning in concert with colleagues or clients, it is more helpful to use a large writing surface. A chalkboard, an erasable board, or large sheets of newsprint propped up on an easel work well. As members suggest an idea or take on an assignment, these can be written large enough to be seen by everyone. If there are disagreements about specific points, they can be quickly noticed and clarified.

An erasable surface communicates the message that ideas are to be played with. They can be listed, rubbed out as the members reject them, and raised to the top or dropped to the bottom of a list of priorities. This encourages experimentation and the free flow of ideas. Newsprint sheets lack that kind of flexibility, but they can be kept intact after a meeting ends. When a group is involved in a planning process over a protracted period, members can save the sheets with their initial ideas. Looking back at the sheets, they can analyze how far they have progressed or notice initial ideas that were forgotten in the flurry of activity.

Black felt-tip markers, as opposed to regular pencils or pens, are part of the standard tools of the planner. They can be easily read from a distance. Thus, members of the planning group are not excluded from considering an idea simply because they cannot read it. Markers used for attendance lists, name tags, and meeting notes have the additional advantage of being easy to photocopy, avoiding excessive clerical work.

Clearly Focused Questions

When planning an intervention, you might be able to manage without a pad and pencil, a computer, a calendar, a directory, a clock, newsprint, a chalkboard, markers, and a phone, but you could not function without these questions:

Who?

Where?

How?

Why?

Why not?

How else?

What if?

Planning is first and foremost a process of asking and answering questions. Sometimes the questions workers ask have definite answers. Often the questions are more speculative and have several alternative answers. Workers anticipate an interview with a client or a meeting with a budget committee by asking themselves and everyone else logical, hard questions about the topic under consideration.

Keith, a staff worker at the Larkin School, which provides services for children who are deaf, blind, and have emotional problems, has designed an expanded summer camp program. Now he is preparing himself for the much anticipated but equally dreaded moment when he must appear before the annual meeting of the board of directors to justify his plan. To prepare his answers to the questions the board members are likely to ask, he puts himself in their shoes (he uses his capacity for anticipatory empathy). Then he rehearses his answers to the questions that he would ask if he were a member of the board. He makes sure that he has the data to back up his answers. Most board members receiving a proposal for a new program are likely to ask the following questions:

Why isn’t our existing summer program adequate?

What did you find the problems to be in last summer’s program?

How do you know that the parents want a more extensive camp program?

What have you done to make sure there will be sufficient enrollment to cover most of the costs?

What makes you think that this new program can fill in some of the GAPs (necessary services or programs that are lacking) in the last one?

How safe and adaptive is the facility you plan to use for the program?

How much will the whole program cost the agency?

Keith knows there will be many more questions. The board of directors has a right to ask these questions, and he must be prepared to answer the questions well. The meeting will be like a tennis or fencing match with questions flying at him from all quarters.

Asking questions is like shining a flashlight in a dark cellar instead of simply stumbling around looking for the fuse box. Questions direct our thinking and protect us from jumping to wrong or incomplete conclusions. Even after he has designed his action plan, this process of asking, finding answers, acting, and then raising more questions continues. It creates an information loop that looks something like Figure 12.1.

Before we look at the specific techniques for moving a plan into action, we present the following interview with a young human service worker who has a great deal of experience in using these tools and techniques. Raquel Fenning is the program coordinator of the Volunteer Services Office at a large urban university.

Figure 12.1

The information loop

Interview Raquel Fenning, University Volunteer Coordinator

I have worked at the university doing volunteer placement for five years now. The first three years I was a student on work-study stipend and then for two more years after graduation, I was hired as a full-time employee to lead the office of Volunteer Placements. When I worked at the Fenway Project, I found volunteer jobs for students. I was responsible for making contact with neighborhood social service agencies and finding out what their volunteer needs were. Then I would draft a paper outlining the agency, its mission, its funding, and so on and finally write a job description for the prospective volunteer. I would check it out with the agency and begin to recruit students who were able and willing to fill it. Most of the volunteers were human service or criminal justice majors or were from some of the more socially conscious fraternities and sororities on campus.

The university put a low priority on student involvement in the neighborhood, so the Fenway Project was sort of an “add on” to the Human Service Program. We placed a few dozen volunteers each semester but mostly we involved classes and clubs in one-shot events in local agencies. We hosted bus trips for senior citizens, a friendly visitor program for seniors who were not able to leave their rooms, after-school recreation clubs for youngsters and teen dances. I couldn’t imagine a better way to learn planning skills than this job. When I worked as the senior citizen coordinator, I met with a senior advisory committee composed of representatives from the seven senior residences in the town. The members suggested trips and activities. Then I would recruit the sororities, fraternities, and other clubs on campus to run them. I’d get the nursing or physical therapy students to conduct exercise classes. I’d try to find a political science or government major to run a current-events discussion group or maybe a seminar. The Fenway Project still exists and is run by students but now they pretty much stick to hosting special events for kids and senior citizens, leaving the regular volunteer placements to our office.

Now that I am a full-time employee, reporting to the Provost’s office, I have a regular budget and a staff of six paid interns and a full-time secretary. The number of students using the program has gone from dozens each term to hundreds. And the students now are from all the majors on campus. Working as a volunteer in a community group for a certain number of hours each year is now a graduation requirement. Many faculty members facilitate the volunteerism by including appropriate community work as an integral part of their courses. So the student not only does the fieldwork but also has to analyze it for a research or concept paper. I still visit agencies, put out recruitment materials, screen students, and ultimately make sure they are evaluated. I also troubleshoot if something goes wrong on the placements either from the student’s point of view or from the supervisor’s point of view. But my staff does a lot of the legwork that permits me to get involved in other mental health issues on campus.

An important part of my job description is to participate in a variety of faculty/staff committees that grapple with “hot button issues” that affect the mental health and well-being of the student population. Since I had been a student here just two years ago and am now a trained human service worker, they place a lot of value on my input. I work on committees that deal with issues facing gay, lesbian, and transgendered students, the uses and abuses of alcohol and drugs on campus and on the committee that oversees political demonstrations and the like.

transgendered

Appearing, acting, or actually becoming (by means of medical procedures) the opposite gender from that which a person is born.

I have just been handed a challenging assignment! I will participate in a newly formed committee which is charged with creating programs, guidelines, and policies to deal with the hottest button issue of recent times: Recently there has been a lot of media coverage of cyberbullying in high schools. Newspapers have carried stories about high school kids (and even some younger children) posting nasty things about each other on websites or in widely distributed text messages. Some high school students have hosted on-line contests to choose the “ugliest girl in school”; they’ve posted messages about who hates whom, which person cheated on an exam, and other really hateful messages. They’ve tricked people into revealing their passwords and have posted photos of victims taken on cell phones without their permission. (See Harris Interactive Research Report on Cyberbullying, commissioned by the National Crime Prevention Council, 2006). This isn’t just kids harmlessly fooling around. Serious consistent teasing, whether in person, or more likely through the anonymity of the web, has resulted in several teenage suicides and nervous breakdowns. In one high school district in Ohio, four students committed suicide in a year; each had undergone serious harassment.

cyberbullying

The use of cyber communication technology to spread information about a person or group, which spreads deliberate, repeated, and hostile opinions or other data intended to harass a targeted victim.

To everyone’s horror, this has moved from high school students—who one can assume are rather immature and might not know better—to college students. In one horrific incident, Tyler Clementi, a Rutgers University freshman, jumped to his death off the George Washington Bridge after a sexual encounter he had in his dorm room was secretly filmed by his roommate. After violating his rights by filming the encounter, the roommate then posted the video on the web (Foderato, 2010; McKinley, 2010). Several of these suicides, like Clementi’s, were of persons who were or were assumed by others to be gay.

The committee has been told by the president of the university to develop programs to deal with all forms of the misuse of technology to harass members of the student body and staff. We are exploring the use of computer software that documents and stores offensive messages, that immediately notifies prespecified recipients of an online threat, and so forth. This way messages can be documented so that perpetrators can be located. We are also planning to hold dorm talks on the misuse of texting, social network sites, videos, and so on. In the spring we will hold a campuswide teach-in aimed at educating students on ways to protect themselves and most importantly, on the serious nature of what might be seen as harmless teasing, especially when done anonymously. We hope to build a community spirit that will make such behavior unacceptable. Of course, the first line of defense is always education but we will also have to draft a set of penalties for abuse when education is not enough. This is a particularly tricky issue since we will have to struggle to find the line where free speech ends and bullying begins.

So my position is very challenging but satisfying. I am so glad I took a course that helped me learn the steps in mounting a program. I will probably stay in this position for a few more years but then I hope to take a degree in public health. I like the idea of being a health educator; it builds on many of the skills I am practicing.

12.2 Phases and Steps in the Planning Process

Planners wear many hats, a different one for each phase of the planning process. In the first phase, donning the peaked cap of a Sherlock Holmes detective, the planner is a gadfly, or troubleshooter. He or she runs around finding problems and noticing when the emperor has no clothes on. In the second phase, the planner replaces the peaked cap with a cowboy-style, ten-gallon hat and takes a giant step back from the problem, looking at the big picture. In the last phase, the peaked cap and ten-gallon hat are put aside for the green visor of the accountant. Now, the planner looks at each part of the plan in depth, figuring out exactly what must be done. Now he or she is a nitpicker, a list maker, and a rule maker and keeper.

troubleshooter

A person who is alert for signs or symptoms that indicate the existence of an actual or potential problem.

In the following section we will look more closely at each of these three phases of the planning process: troubleshooting, magnifying, and microscoping.*

*To read more about the steps involved in the three phases, see American Association of University Women (1978); Dale, Magnani, and Miller (1979); Dale and Mitiguy (1978); Frame (1995); Kettner, Moroney, and Martin (2007); and Schram (1997).

Phase 1: Troubleshooting

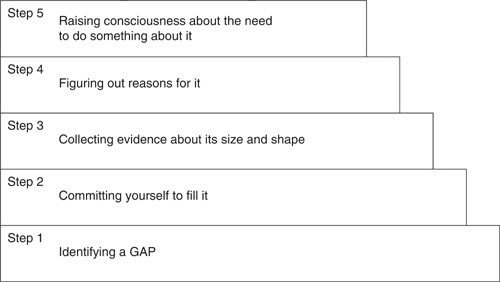

Step 1: Identifying a Gap

As shown in Figure 12.2, the planning process begins as soon as Raquel or another Fenway Project staff member says:

Something is wrong with how that is done!

or

Something is missing from…!

or

Wouldn’t it be wonderful if…!

or

There oughta be a law about…!

Often we identify a GAP, without realizing we are doing so, when we are having a good gripe session. Listen in as Lowell, a human service student, complains about the difficulty he had finding the appropriate social services for his elderly aunt:

GAP

A necessary service or resource that is lacking in a program or in services that might help solve a problem.

Over Easter break I spent a lot of time with my Aunt Elsie, who is 82 years old. She’s in the hospital with a broken hip. I knew she would need some homemaking help and maybe some emotional support when she returned home. She lives alone in a small house. I don’t know my way around this city. The social worker at the hospital was either too busy with more serious cases or really didn’t know much about the resources for elderly people. Boy, was that frustrating! There really ought to be a place where elderly people or their relatives could go to get current information on home-care services. Even more important, I could use someone to steer me to the good programs and warn me about the ones to avoid.

Figure 12.2

The process of trouble shooting a problem

Lowell was describing what now exists and then visualizing what ought to happen. In between the two, “the what is” and the “what ought to be,” there is a yawning cavern that a person is likely to fall into. We call that hole a GAP.

Sometimes a GAP is identified by a person who has a desperate need for a resource that he or she cannot locate, that does not exist, or that is functioning poorly. At other times a professional human service worker notices an unmet need and brings it to the attention of his or her supervisor or board.

In Figure 12.3 we have listed a few examples of people describing “what is” and visions of “what ought to be.” In between the “is” and the “ought” lies a GAP that needs to be bridged by social service planning.

Example: A Professional Identifies a GAP

A doctor working in rural Alabama was surprised at how few patients came into the hospital to be treated for AIDS or HIV. Although AIDS is often thought of as an urban phenomenon, she knew that was not accurate. She had a hunch that people in southern rural towns, where everyone knows everyone else’s business, were afraid to even ask for AIDS testing. The strong fundamentalist religious values of the region attach an especially noxious stigma to AIDS, with its implications of homosexual behavior. So, dipping into her own wallet for start-up funds, she began a public education program called ASK, which stood for AIDS Support through Knowledge. These are some of the outreach strategies she used:

Figure 12.3

Examples of social service GAPs

WHAT IS This Is What Exists Now THE GAP WHAT OUGHT TO BE This Is What Ought to Happen

“Every Sunday as I sit in church, I notice this group of people who are obviously retarded sitting in the last few rows. They don’t bother anyone, and they leave right after the service. But they seem so lonely and out of it.” GAP “These people are newcomers to our church and ought to be welcomed by the congregation. It would be nice if they could stay for the hospitality hour so members and their children could get to know them. That’s what our church is supposed to be all about.”

“Every week the hospital in our town releases people who have emotional disturbances to live on their own in the community. A lot of them have lost contact with old friends or relatives. They’re just drifting. They live in cheap boarding houses, often on skid row, where they have nothing to do and little to look forward to” GAP “There ought to be some place they could go during the day if they are not working or on weekends if they are. They need to be with other people, especially ones who can understand what they’ve been through and know how hard it is to adjust after years spent in and out of an institution.”

“Every year the YMCA has a junior olympics for the kids who attend gym classes. This year, because they’ve removed a lot of the architectural barriers, my son who is wheelchair-bound attends the sports program. He’s going to feel very left out if he’s not included in the big event, but everyone seems too worried about problems of safety and insurance to include the kids with handicaps.” GAP “We ought to offer the kids with physical handicaps a chance to have the same type of activities all the others e

She set up an anonymous information telephone hot line.

She convinced a popular disc jockey to play a rap song about AIDS over the local radio station.

She placed ads in newspapers.

She sponsored a group of high school students, who performed a play about AIDS at schools and churches.

Eventually, many people who worried they might have contracted AIDS found the courage to come to the hospital for testing and care.

In Designing and Managing Programs: An Effectiveness Based Approach, Kettner et al. (2007) point out that many people who might need services seek them out only when the possibility of actually receiving them exists. Because people have such low expectations, they often do not even perceive that their GAP is a legitimate one or that they deserve to have it filled.

After a rape crisis center opens in a town, instead of seeing a reduction in the rape statistics, we are likely to see them increase. It looks as if the situation is getting worse, but what might actually be happening is that victims, especially of date rape, who used to feel that there was no possibility of getting justice and who endured their pain in silence, are finding the courage to come forward and report the crime. Now there is a chance that they might be protected and that the abuser might be punished.

Step 2: Committing Ourselves to Filling the Gap

Once it has been stated that a GAP exists, someone has to commit himself or herself to the long, painstaking, often thankless planning tasks that can fill it. Unfortunately, gripe sessions too often end with little to show for them but shared frustration. Often people will say:

What can I do? I don’t know anything about starting up a program.

or

But it has always been that way!

These statements express widespread feelings of powerlessness, but they do not reflect reality. Many programs have grown out of an informal discussion in someone’s living room. Park benches in schoolyards where parents gather to talk about their children, their families, and their hopes for the future are often fertile fields for new program ideas. For example, the widely translated, best-selling book Our Bodies, Ourselves (Boston Women’s Health Book Collective, 2006) grew out of a small women’s consciousness-raising group that met informally in the 1970s. The women began asking each other questions about their special issues of health and sexuality. Discovering how little any of them knew, they started doing research. Finding the books limited and written mostly from a male perspective, the women decided to write their own book. That first book (revised many times) was followed by Ourselves and Our Children (1981) and The New Ourselves, Growing Older (1994), among many others, and translated into several languages.

consciousness raising

The process in which people are provoked into giving an issue serious thought, perhaps through suggestion of new points of view to be considered.

Programs designed to fill GAPs do not necessarily need vast sums of money and expertise. They grow out of someone’s capacity to keep plugging away, aided by a fertile imagination, self-confidence, and a good support network.

support network

The people and places in our lives that offer ongoing practical as well as emotional help.

Example: Members of a Church Commit Themselves to Filling a GAP

Several years ago, one of the authors of this text was visiting a friend who had just returned from delivering a paper on “supervised visitation” at a professional conference (Speigel, 1992). Surprised that she had never heard that term, because she thought she “knew everything about social programs,” the author admitted that she had no idea what supervised visitation was. Her friend explained that the supervised visitation program she directed was the brainchild of a member of a local church. Her minister had told the congregation of the problems that families face when an incident of abuse or neglect made it impossible for one of the parents to be left alone with his or her child. But, hoping that the abuser would have the incentive to change his or her behavior, so the family unit could eventually be preserved, the court did not want to sever their relationships. Judges mandate that the abusing parent can visit with the child only if a neutral, trained observer is present to guarantee safety during the visit. However, this arrangement is almost impossible to manage for most noncustodial parents. State social workers are overburdened, and private therapists charge high fees.

So this woman had the idea of using the church as a place for supervised family visits. By having several families come at one time in groups, more people could be served for a low cost. Also, families would realize that there were others who grappled with similar problems.

No event, no matter how often it is repeated, is ever taken for granted. Getting a message out to the public takes great imagination and attention to detail. These students are sponsoring a recruitment drive for volunteers.

The following is the program she designed:

Each Saturday, eighteen families gather at the church, nine in the morning and nine in the afternoon.

The custodial parents bring their children to the church, where they are met by volunteer facilitators and go off for a snack.

The custodial parents gather in another room for a support-group session.

The noncustodial parents then arrive, and the facilitators and children join them at a table in the social hall. The table is set with age-appropriate games and craft materials.

The noncustodial parents and children interact for an hour while a facilitator sits a few feet away, unobtrusively monitoring the contact. The observer intervenes only if a child is in immediate danger or an inappropriate question is being asked or comment is made.

The children and their custodial parents leave.

The noncustodial parents go into a mandatory support-group meeting.

The facilitators get together to review how things went and make suggestions.

In the afternoon, the program repeats with the second group of parents and facilitators.

The role of the professional social worker, the only paid staff member, is to keep all the balls in the air: training and recruiting the volunteers, most of whom are students, church members, and interested citizens. The worker keeps in contact with the courts and the Department of Social Services.

The program is overseen and the funds are raised by church members as a tangible expression of their convictions about the importance of family values. Because the space is free and all the facilitators are volunteers, the yearly cost of the program is primarily the professional’s half-time salary. So far, they have been able to raise this amount through a variety of fund-raising campaigns. Often it is easier to raise money for a very specific program such as this one than for a more amorphous general appeal.

Some people accurately define a problem and immediately propose solutions. But if they start to act too quickly, they run the risk of becoming a general without an army. Along with her commitment to act, this woman at the church did careful research before she proposed her idea. She understood that without solid data about the problem, she would never have been able to solicit the support of the congregation, the courts, the Department of Social Services, and the thirty-two volunteers who give up their Saturdays to help their neighbors.

Step 3: Collecting Evidence About a Gap

Remember the difficulties encountered by Lowell, the human service student, as he tried to find services for his elderly aunt? Although Raquel agreed with Lowell that there appeared to be an information GAP about services for the elderly in his hometown, she knew that they had to be sure it existed. Maybe Lowell simply couldn’t find the information he needed. She decided to help him collect evidence to support (or perhaps refute) his assertion that information about geriatric services is not readily available.

They begin their research by collecting data in the public library. They look through directories (both hard copy and online) to find social services for the elderly, especially those that help maintain elderly persons in their own homes during a recovery period. They plan to interview people at some of these agencies to get information straight from the source. Before they interview anyone, though, they write up a list of questions to ask, examples of which are shown in Figure 12.4. This way they can make sure that they get the same type of information from each interview. Of course, every GAP one is researching will need specially tailored questions. But these are samples of questions that might be asked.

Figure 12.4

Sample interview questions on services for the elderly

COLLECTING EVIDENCE ABOUT THE EXTENT OF A GAP Services to the Elderly in Aurora

I. Questions to ask organization staff workers:

How many senior citizens do you have contact with, either in person or through newsletters?

What strategies do you use to get information out about available services to the elderly population and to social agencies?

What written guides do you have on elderly programs? Which of them seem most useful? What obstacles stand in the way of reaching some of the elderly?

Which groups of elderly citizens and their families do you feel are not being reached?

How great a need do you think there is for some type of information service for geriatric programs? What are your suggestions?

II. Questions to ask individual senior citizens or their families:

How did you hear about this particular organization (housing project, nursing home, recreational center, or whatever) you attend?

If you needed home care, a senior shuttle bus, meals on wheels, day care, or a nursing home, to whom would you turn for that information?

How easy is it to get information when you need some kind of services? If it is difficult, why do you think that is so? What are your suggestions to increase knowledge of resources?

It is important that the people Raquel and Lowell interview represent a cross-section of elderly service workers and consumers. They need to know in whose eyes the GAP exists. The people (and their programs) they interviewed are listed in Figure 12.5. Notice that their hunt for evidence about the GAP also included census data and other library resources.

From their interviews and reading, Raquel and Lowell decide that their initial hunch was correct: Information about available services is not getting to everyone who needs it, especially when they are in crisis. Both consumers and professionals agree that some central source of updated information is sorely needed. Raquel and Lowell’s review of the census data reveals that the elderly population in this area has risen by 20 percent in the past ten years. The articles they read predicted that it will continue to grow.

Now Raquel and Lowell have evidence to show that outreach to the elderly and to the general public about the full range of elderly home care services is a legitimate GAP. Some agencies call this data-gathering process conducting a needs assessment. Once they are sure they have a legitimate GAP that needs to be filled, they must find out for what reasons it exists. To do this, they move on to the next step.*

*A useful resource Lowell could have used to generate ideas about agencies to look for is the book Making Aging in Place Work (Pastalan, 1999).

needs assessment

Methods used to find out precisely what one particular person, group, or community needs to solve its problems and expand opportunities.

Figure 12.5

Sources of information about services for the elderly

COLLECTING EVIDENCE ABOUT THE EXTENT OF A GAP Services for the Elderly

I. People we will need to talk to:

Citywide council on elderly affairs in the mayor’s office

Local chapter of AARP (American Association of Retired Persons), National Council of Older Americans, or OWL (Older Women’s League)

Nursing Home Director’s Group and some residents of local nursing homes

The Homecare Corporation

The Gray Panthers (a self-help elderly social action group)

Project manager and residents at the Susan B. Anthony Elderly Housing Project

The Methodist church’s friendly visitors program

II. Publications we will need to read:

Citywide and community newspapers (large-print version, if there is one)

Newsletters of any senior citizen clubs or groups

Directory of services for the elderly

Census data for the area

Step 4: Figuring Out Causality—the Reasons for the Gap

As Raquel and Lowell were collecting evidence about the size and shape of the GAP in referral services, they were constantly asking their informants “why” questions such as:

Why do you think the public has so little knowledge about your program?

Why do the booklets you publish seem to reach one group of professionals or elderly citizens more than another?

Why haven’t you tried using other media to inform them?

The answers to these questions begin the difficult process of estimating the reasons for the GAP. Reasons will suggest remedies. Although we can never be absolutely certain about the reasons for a problem, the process of identifying possible causes and then ranking them in importance is a vital one. It creates the foundation upon which the whole planning process is built.

Figure 12.6

Possible reasons for a GAP in referral services

POSSIBLE REASONS FOR A GAP Referral Services for the Elderly

Information about elderly services is not reaching enough people because:

The directories of services that do exist are all in the English language, and the print is often small and hard to read.

Directories of services for the elderly are not distributed widely enough. They are available only at social agencies or hospitals.

Directories of services for the elderly seem to be very specialized, concentrating on only one type of service. Often they don’t mention alternative services available at other agencies.

The elderly are often homebound and use television and radio more frequently than books and newspapers to get information.

Often the elderly and their families don’t prepare for emergencies and must do their planning when a crisis occurs, when they are least able to seek out resources rationally.

Many people assume that all service programs for the elderly are charity and resist exploring resources that might have a social stigma.

Programs change so often that staff are unaware of new ones or those which have been discontinued.

The best referrals are made by knowledgeable people, not directories; however, agencies are short of experienced staff.

Figure 12.6 shows the list of reasons Raquel and Lowell created after studying the interviews and reading journal articles on the subject. See how program ideas seem to flow logically from each of them! There is no way, of course, that they can design one program that deals with all the reasons. So they rank the listed items, giving some a higher priority than others. Finally, they will have to decide which reasons to deal with first.

Now the two young planners are ready to go public, looking to find others who will join them in filling this unmet need.

Step 5: Raising Consciousness About a Gap

Even after a GAP has been identified, evidence about its size, shape, and causes has been marshaled, and some possible reasons for it have been outlined, the demand that it be filled can fall on deaf ears. Lots of other people must agree that it is a problem before it can move up to the top of the agenda for the client, the agency, the bureaucrats, and the legislators.

Raquel and Lowell, enlisting the assistance of the students in a class on aging at their university, conduct the following consciousness-raising activities to spread concern about their GAP:

They write up a brief report, presenting their evidence that there is a lack of information about available resources and giving examples of the havoc it wreaks on the elderly homebound.

They meet with the president of a senior citizen center to solicit his or her group’s support.

They meet with the chairperson of the Council on Aging and get his or her enthusiastic support.

They get themselves invited to speak about the problem at two local churches, a temple, and a mosque.

They convince the editor of the local newspaper to write a feature story about the plight of elderly homebound people who cannot find support services.

They speak on the local cable TV station about the GAP.

Phase 2: Magnifying

Having gathered evidence and marshaled enthusiastic support, Raquel and Lowell are now ready to begin magnifying. During this phase, they will collect, sort, and then choose concrete program ideas—vital components of the program design process. Figure 12.7 shows the steps they follow.

magnifying

Looking at a program or problem within the larger context of the community, laws, professional field, and so forth.

Now, Raquel and Lowell’s imaginations can work overtime. Although looking for innovative ideas, they do not simply dismiss as old hat program ideas that already exist. Actually, few really new ideas are ever born. Most program concepts are variations on a few central themes. They borrow a technique from here, an approach from there. They recombine basic program interventions, giving them a new twist, one that is especially suited to this population, problem, and town.

Before they design their plan, Raquel and Lowell need to be reassured that although we strive for a perfect solution, in the real world, one will rarely be found. Program designs have to be flexible and responsive to constant feedback. As soon as they have planned the program, they will want to start redoing the design. Programs are organic, living creatures with unpredictable demands and personalities.

Figure 12.7

The process of magnifying the problem

Step 1: Conducting an Inventory of Other Programs

Throughout this book, we have stressed the critical importance of obtaining firsthand knowledge of program resources in the local community. But when designing an action plan, we look within and far beyond the boundaries of our own town because program ideas cross-fertilize from one region or country to another. For example, the concept of the ombudsperson—a red-tape cutter—now found in many U.S. city halls, universities, and hospitals—was borrowed from Scandinavia. The program design for the Samaritans, a volunteer suicide hot line, was imported from England. Creches—overnight shelters for young children whose parents have to leave them in emergencies—originated in France.

After visiting a poor developing country in Latin America, a social planning student observed:

On this trip I was impressed by the way in which ideas flow in all directions. When I visited the country’s only residential school for the blind, staff members told me how much they wanted to study in the United States. They wanted to learn about the newest Braille machines and mobility training techniques. Their country is very far behind us in special needs programming. I noted with regret that all their new public buildings are being constructed with complete disregard of the architectural barriers that exclude people who are physically disabled. In the future, when they become more conscious of integrating people with special needs, they’ll have to spend thousands of dollars replacing steps with ramps and modifying bathrooms.

Yet, surprisingly, they had some very innovative approaches that far outdistanced ours. For example, to meet the needs of urban, two-worker couples with elderly disabled relatives, they have constructed nursing and old-age homes. Yet, wanting to keep the traditional, extended family as intact as possible, they arrange to transport the elderly residents back to the homes of their relatives for weekends and holidays. I’ve not heard of many homes for the elderly doing that in the United States. Because we are concerned about the increasing isolation of the elderly, I suspect that idea will eventually catch on here.

This was a good lesson for me. Although we are advanced in some areas, we still have plenty to learn from a developing country.

Sometimes program approaches are transplanted whole from one place to another. At other times, however, new program ideas leapfrog off each other. For example, in the travel section of our newspaper several years ago there was an article about a travel agency that arranges for tourists to stay in elegant castles and manor houses when visiting foreign countries. A few years later, other tourist companies began arranging accommodations in more humble kinds of homes in both Europe and Latin America. Eventually this commercial travel idea reached the human services. It changed from a profit-making enterprise into a nonprofit support network for a special population. A senior citizen council in a Midwestern city set up a vacation home-exchange program for elderly citizens on limited incomes. In this plan, older people living in modest homes can arrange a low-cost holiday trip. For only the cost of transportation, they can explore the countryside or a big city by exchanging their apartment for that of another elderly person. Because improving the quality of life for our elderly is an increasingly important concern, this innovative idea is likely to spread. Perhaps as a logical extension there might be a home-exchange program for physically challenged people and so on.

Program ideas also leapfrog from one problem area to another. The GAP in referral services for the elderly that Raquel analyzed has been filled in one local community by a program called the Geriatric Resource Center. Two years before it was begun, a divorce resource and mediation center was started in a nearby town. Several years before that, a child care resource center was begun. We cannot be sure that each was the ancestor of the next, but the program format of specialized resource centers that help a specific population has certainly spread.

Once you see yourself as a planner, you are likely to get new program ideas almost every time you read a newspaper, watch a television show, or attend a lecture or seminar. You will not be able to act on all of them, but you can store program designs away for future use.

Step 2: Brainstorming Ideas

Brainstorming is a very simple yet elegant planning technique that quickly produces a great many ideas, some mundane and impractical, a few marvelously creative (Michaiko, 2006, Osborn, 1963). It energizes the staff member of the Office of Volunteer Services, freeing them of their usual reserve by sweeping them into the contagion of shared problem solving. They do it at staff meetings in groups of three. Everyone can easily be heard and is encouraged to participate. A brainstorming assignment must be very clear. It begins with a question, for instance:

brainstorming

A technique in which people generate ideas under time pressure and without judgment so that their most innovative thoughts can flow.

If we had $1,000 more in our budget, what programs would we initiate?

If you were made dean of this college, what are the ten most important changes you’d make?

If we open up this program to persons who are blind, what parts of it would have to be changed? In what ways?

A time limit of five or ten minutes is set for each session. The time pressure encourages members to keep throwing out ideas. The group leader begins the creative juices flowing by suggesting a few ideas of his or her own—the more innovative the better. Participants are told that there is a premium placed on far-ranging thinking. There are a few simple rules for brainstorming (Coover, Deacon, Esser, & Moore, 1985; Dale & Mitiguy, 1978; Siegel, 1996):

Do not censor your ideas; let them flow. Even if they sound silly, impractical, or naive, they can be sorted out and discarded later.

Do not censor anyone else’s ideas by judging them or by communicating distaste, scorn, or ridicule.

Give encouragement and support to others and expect it from others.

Build on each other’s ideas, use them, and change them.

Move quickly and try to get as many ideas out as possible.

List ideas on paper so that they are not lost in the flow of talk.

Step 3: Collecting and Ranking Ideas

At the Fenway Project quarterly retreat, the student staff members were asked to brainstorm ways to spend the grant they were awarded by the Office of Student Affairs. The ideas they came up with were listed on a chalkboard and then divided into categories:

Senior citizen programs

Youth after-school programs

Programs for developmentally delayed adults

Teenager programs

Special one-time work projects

Community fairs

Then they divided the categories according to the following criteria:

Programs we can do ourselves

Programs we can try to get other groups to sponsor

and according to still another dimension:

Programs that do not cost money

Programs that do cost money

Then the student staff edited the lists, discarding ideas that seemed impractical or that evoked little interest. They put check marks next to those that excited almost everyone. These lists will be carried over from one quarter to the next. As new ideas come up, they will be added. If a human service major wants to do a special internship at the Fenway Project, he or she can look at this list to see what program ideas are waiting to be developed.

The Fenway Project also keeps a wish list. Staff members suggest equipment or funding they would like to obtain if there is any money left at the end of the fiscal year. Three weeks before the budget closes, they review the auditor’s printouts. They see how much money they were allocated and how much they have spent and then pick and choose what they can still afford to buy. If any individuals or organizations offer to make monetary donations, they refer to their wish list and suggest an item. The current wish list of the Fenway Project looks like this:

A laser printer, a scanner, and a digital camera

A paint job for the office

Slides to use for class presentations

A catcher’s mitt and a left-handed fielder’s mitt

A new coffee urn

Step 4: Doing a Force-Field Analysis

After a program idea has survived the sorting and ranking process, it is time to analyze its chances of success. To do this the students use a simple but effective technique called force-field analysis. They first look at the forces that might help the program get started and the barriers that are likely to stand in its way. They gain confidence by reviewing the positive factors but are also alerted to the barriers posed by the negatives. They look at how they balance out.

force-field analysis

A systematic way of looking at the negatives and positives of an idea or event in order to understand it fully, anticipate problems, and estimate chances of success.

Some Fenway Project youth staff are working with Hi-Teens, a club of adolescents who live in the local public housing project. The staff has decided that the group needs a really good activity to pull the members together into a cohesive unit. They brainstormed with the teenagers and analyzed their list of ideas, and everyone agreed that they wanted a weekend camping trip. Now they must think through how likely it is that they will be able to plan and successfully carry out the idea. Systematically, they list the positive and negative forces, as in Figure 12.8.

If the negative forces are too overwhelming, the youth staff will move on to the next idea. Many of these inner-city teenagers have already experienced too much frustration and failure in their lives. They need a program that is grounded in reality and success. Their force-field list looks reasonably balanced. It will take a lot of work to turn those negatives into positives, but they think they can do it. If ignored, the negatives might sabotage their best planning efforts.

Figure 12.8

A sample force-field analysis

FORCE-FIELD ANALYSIS Topic: Hi-Teens’ Weekend Camping Trip

The Positives + (What we have going for us)

We have been on several one-day trips, and they’ve worked out well.

It’s January now, so we have lots of time to make a reservation at a camp site for the spring.

We all get along very well.

Our group leader has a lot of camping experience.

Because most of the members voted for this idea, we should get good cooperation from them.

The Negatives – (What might get in our way)

We have no money in our treasury.

Some parents may refuse to give permission, especially if it’s boys and girls together.

The camping sites are pretty far away, and we don’t have any transportation.

Carlos, our group leader, has finals at college in the spring and may not have the time to take us.

Figure 12.9

A sample force-field analysis

FORCE-FIELD ANALYSIS STRATEGY PLANNING

The negative force Strategies to overcome the negative force

Some parents may refuse to give permission, especially if it’s boys and girls together.

Ask one or two parents to chaperone the trip.

Go in two separate groups of boys and girls; combine for some activities.

Have the overnight at the house of one of the members.

Have the parents who are likely to give permission talk to the ones who are against it.

Have the group leader meet with all the parents to discuss the trip.

After completing the force-field analysis, the teens brainstorm strategies that might overcome or neutralize those negative forces. Figure 12.9 lists the strategies to overcome one negative force listed in Figure 12.8, “parents’ resistance to a coed trip.” Now, they need to construct an action plan, making sure that potential obstacles to their plans are dealt with and that everything they have decided to do is clear to all the members.

Step 5: Creating a Program Proposal and Making a Work Plan

No matter how informal the group, it is imperative that the program plan the group hopes to implement be written down so that everyone can review it fully and those who become involved later on can be accurately oriented to it. The program proposal will be the road map. It keeps folks on course and invites others (especially funders) to come on board. Figure 12.10 lists what the proposal should include. A book the teens found useful was Proposals That Work (Locke, Spirduiso, & Silverman, 2007). As a first step in drafting the plan, we need to look back at our negative forces. How can we overcome the negative forces? In the minutes of the teenagers’ meeting (prepared by Carlos, the college student volunteer), you can see how they began that process:

We voted eight to one that we would have a two-day camping trip in the country in the late spring. We want the trip to include both boys and girls. We will schedule it for a weekend after Carlos’s finals. We will have a meeting with all the parents this month to try to convince them to let us go and see what help they can give us. Some of the boys worried that the parents would resist. So then we spent more time figuring out what to do to get the parents to say okay.

In Figure 12.9 you can see some of the strategies they came up with.

Figure 12.10

Writing a program proposal

* Many funding agencies will have their own special format to follow.

** For a sample program proposal, see Schram (1997, pp. 220–226).

The proposal should include:*

Title page—with name of program, who it is being presented to and by whom.

Abstract—a brief overview of the agency, problem (GAP) program activities, funding request, and planners. No more than one scant page, the abstract should be very tight and clear. It may be all that is ever looked at if many proposals are in a pile in a funder’s in-box.

Table of contents—each part of the proposal should be numbered for each reference when the program is being discussed.

Problem statement—What (GAP) is this program trying to fill? How did the problem get identified, how long has it been going on, what are its consequences? This part would include backup data, surveys, professional articles, anecdotal evidence.

Background to the problem—brief information about the agency or persons making the proposal, who does it serve, how, when did it begin, staff, funding, facility, and geographic area.

Goals of the program—this includes hopeful outcomes spelled out very operationally and in very specific terms.

Proposed activities—Exactly what are you planning to do, when, and how? What staff will be needed, what facility, what equipment? This should also include a work plan or time line in this section or a separate one.

Budget—How much money will be needed for exactly what, and how much will need to be raised for the new program, and what in-kind donations are expected?

Evaluation—What methods will you use to assess how successfully your program activities have met your goals or hoped-for outcomes, over what period of time?

Additional supporting documents—this section would include bibliography if applicable, charts, and letters of support or concern.**

They ended their meeting by deciding that they would raise the money through a car wash. It would be held on Saturday from 11:00 a.m. to 4:00 p.m. in front of the local housing project. Tiger and Arnie agreed to be in charge of it.

That plan may sound pretty clear, but it needs to be spelled out in greater detail, and it needs an alternative. “The best-laid plans of mice and men (and women) often go astray.” Every planner knows Murphy’s Law:

IF ANYTHING CAN GO WRONG, IT WILL!

Whether you are asking for extra funding or have the funds but need permission from the director or staff to embark on a new program, it is critically important that all the details of the proposed plan be set down on paper. In the process of doing this, the planners themselves will become much clearer and ultimately more persuasive. The proposal shows that you have done your homework and that you have a feasible plan and credible planners.

If Murphy’s law is correct, the young people better plan the camping trip and car wash with some fallback arrangements. There must always be plans A, B, C, and D. Perhaps they cannot get a majority of the parents to approve the co-ed overnight trip, which is plan A, and, therefore, plan B might be that they will try to get the parents to agree to a one-day coed trip. Plan C could be separate overnight trips, one for the girls and one for the boys.

Because it might rain on the weekend they choose, they will book an alternate date for the next weekend. If Carlos cannot go because of his schoolwork, they will ask Mr. Devon, the gym coach, if he would be willing to go.

Of course, we can never anticipate all the twists of fate, but good planners try to cover as many bases as they can. Clients do not need workers to protect them from all possible failures. Rather, they need workers who encourage them to plan realistically.

Creating a sensible contingency plan is a problem-solving skill that is valuable in every phase of work, school, and social life. Parades are often rained on, but good planners bring umbrellas!

A vital part of the process of drafting a plan is estimating how much money it will take and how much money the group has or can raise. Although all of us resist making a budget, it is surprising how much clearer every part of a plan becomes when we have finished the budget-making process. Finances are always the bottom line. That does not mean that everything must cost a lot of money. As we get more skillful, we find many ways to get donations and make do with very little.

Phase 3: Microscoping

For the microscoping phase of the planning process, we take off our creative, think-big hat and put on the green visor of the accountant. Now we must focus all our attention on the minute details of our specific plan. We must make sure that it will work as smoothly as possible. The steps we follow are listed in Figure 12.11.

Figure 12.11

The process of microscoping a problem

microscoping

Looking at a program or problem and seeing within it all the component parts and steps of action needed.

In this phase, we must nail down vague ideas. Using pad and paper, computers, date-books, clocks, and web sites and directories of resources, the teenagers make checklists (and double-checklists). The mindset of the microscoper is neat and orderly, leaving little to chance.

Many experienced workers have adopted the anxious stance of the microscoper after failing several classes in the “school of hard knocks.” A student intern at the Fenway Project wrote the following about his fieldwork:

I still carry with me the vivid memory of facing sixty disappointed, angry adults and children on a hot street corner. Although I had booked the buses for their annual family picnic at Riverside Amusement Park, I had neglected to double-check the bus company’s arrangements. The buses never showed! Many of these folks had planned their vacations around this yearly outing. Few have the cars or money to take their own trips to the country. They counted on my planning ability, and I hadn’t come through for them. Now I’ve learned to double- (or even triple-) check every time I lease a bus.

Every human service worker can recount a story of a catastrophe that destroyed a program. Perhaps the DVD for the cartoon show for little kids did not work, or the CD player for a dance was broken, or the staff member in charge of food bought only half the number of frankfurters needed for the barbecue.

Mistakes creep into our work in subtle and not-so-subtle ways. Chances are you will find in your own mail at least one advertisement for a conference, a meeting, or an open house that has the wrong date on it or fails to note that baby-sitting is provided or that there are special rates for students and senior citizens. Perhaps you have encountered the frustration of receiving an invitation mailed so late that the event has already passed.

With charts, graphs, checklists, and yellow stick-on papers on the refrigerator door, the microscoper tries to minimize small errors that can destroy months of hard work. Although there are no guarantees against errors, if we share the work of planning with others, we tap a large reservoir of energy and skills. This offers some protection.

The following anonymous poem hangs on the wall of the Fenway Project as a reminder of Murphy’s Law:

I have a spelling checker

It came with my PC.

It plainly marks four my revue

Miss stakes I cannot sea

I’ve run this poem threw it,

I’m sure your please to no.

It’s letter perfect in its weigh,

My checker toll me sew.

Now we will look at each of the steps in microscoping that can turn proposed programs into solid realities.

Step 1: Building a Resource Bank

Every action plan must draw on its own resource bank. Planners need to figure out what is needed and what resources are readily available. Each of us is an integral part of a network of friends, family, peers, and work associates. They share many of their resources with us, and we reciprocate. We turn first to them when looking for resources. No person or group, no matter how poor or troubled, is totally devoid of resources. By asking questions, we stimulate people to think about their own and others’ resources.

resource bank

People, places, services, or written materials that help people meet needs and reach goals.

After exploring all their contacts, the members of the teen group did a resource analysis so that they could see what they were still missing and how they might fill any GAPs (see Figure 12.12 for a chart of some of the resources they needed). All the ideas about where to find resources had to be carefully checked out—some materialized and some fell through. The creative hustling continued. The teens were surprised to find that most of the people they asked to help them said “yes.” Generally people are very willing to lend a hand if asked to donate a specific resource or service that suits their capacity and time schedule. They are more likely to continue helping if their contribution is acknowledged (Ries & Leakfield, 1998; Shore, 1995). We can never say “thank you” too often.

Sitting at a computer is much less glamorous than other parts of the planning process, but when a file or report is missing, the cost in human energy and pain can be great.

Figure 12.12

A sample resource analysis

Step 2: Specifying and Assigning Tasks

Most of us feel totally overwhelmed at the beginning of any new action plan—perhaps we are anticipating putting on a carnival, forming a tenant committee, or returning to school after twenty years of homemaking. New staff members or volunteers inevitably experience that initial panicky question:

Can I speak in front of a room full of faculty members?

Can I take fifty screaming kids to the circus?

Can I walk through that neighborhood?