Final paper

American Lives: Sitting Bull and the American West

Sitting Bull was born on the northern Great Plains (in present-day South Dakota) in about 1831. He distinguished himself as an accomplished buffalo hunter and warrior among the Hunkpapa, part of the seven-tribe confederacy that made up the Western Sioux, or Lakota, and his brave record and high rank among his people led to his designation as a war chief. Also a holy man responsible for his people’s spiritual well-being, Sitting Bull initially encouraged the Lakota to interact with White Americans who sought to trade and barter with Native Americans at various trading posts established along the Missouri River.

However, as increasingly more White traders, and the U.S. Army, moved into the region, relations between the Lakota and the Americans worsened. Discovery of gold in the Dakota Territory and western Montana in 1874, and the gold rush that followed, led to a series of battles that resulted in the cession of many Native American lands and the confinement of Native Americans onto designated reservations on the Great Plains. Sitting Bull emerged as the leader of all the tribes and bands who refused to sign treaties with the U.S. government. He became a symbol of Native Americans’ final resistance to the encroachment of White settlement.

Sitting Bull and his followers adopted a defensive strategy and experienced significant victories in keeping the army at bay. In June 1876 he oversaw the warriors who decimated Lt. Col. George Armstrong Custer and his cavalry regiment at the Battle of Little Big Horn, in eastern Montana territory, in which Custer and 262 of his men died. In the aftermath, however, the army gained the upper hand in the conflict. Sitting Bull fled to Canada with many of his followers, but when he returned to the United States, he was arrested and jailed for 2 years.

Upon his release, Sitting Bull tried to comply with the government’s assimilation program by briefly becoming a farmer. The arid plains environment made farming without irrigation nearly impossible, however, and his crops failed. Despondent that the traditional Native American lifestyle was no longer an option, Sitting Bull grasped for any opportunity to earn a living. He traveled for a season as a performer in Buffalo Bill Cody’s Wild West Show, reenacting his peoples’ defeat for White audiences in the eastern United States and Europe. Although the experience proved painful and humiliating, he endured multiple performances before crowds who came to see an authentic Native American.

When a new religious movement known as the Ghost Dance gained popularity among the Lakota, Sitting Bull once again became a target of government concern. Officials saw him as an apostle of the movement, which envisioned Native American sovereignty and prosperity and strove for the decline of White control, and they issued orders for his arrest. On December 15, 1890, a conflict erupted between police and Sitting Bull’s supporters, resulting in the death of one of the arresting officers and Sitting Bull himself (Anderson, 1996).

Sitting Bull’s death signaled that Native American resistance was near its end. The lands that Sitting Bull and other Native American tribes sought to defend embodied “the West,” that vast space in which industrialization, adventurism, discrimination, and technology coalesced to forever change the United States.

1.1 Western Settlement

When European settlement began on the Atlantic coast in the 17th and 18th centuries, the western frontier was Ohio and the Old Northwest. For the Spanish explorers arriving in the South and West, the frontier was not the west but the northern region of Native American cultures and French and English settlement. Beyond the colonial period, as American settlement moved to fill up the land beyond the Atlantic coast, the West moved as well. The Old Northwest became the Midwest and the frontier pushed on to the Great Plains, to the lands that Sitting Bull and other Native Americans called home.

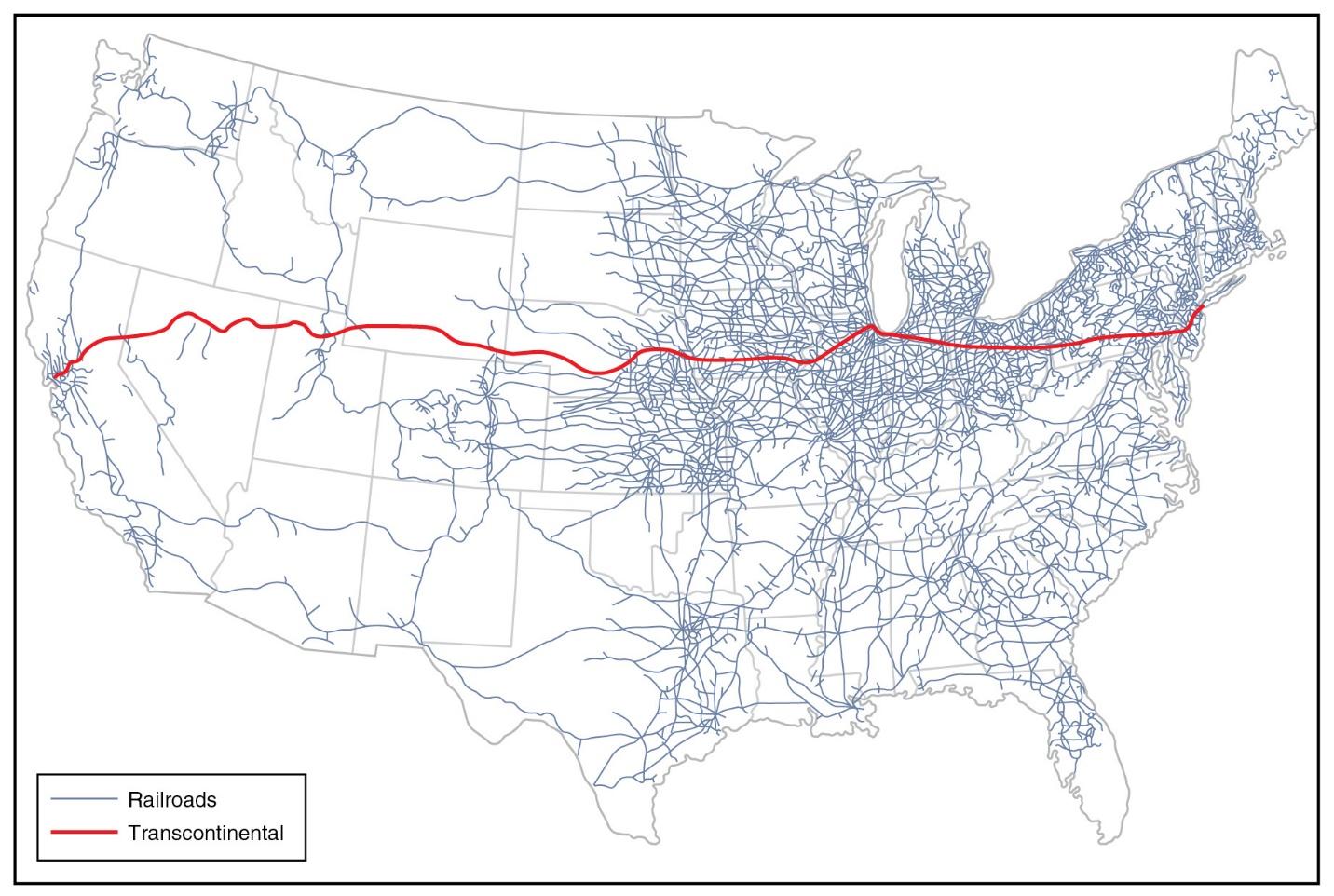

Urged forward by new technologies such as the railroad, mechanized farming equipment, and barbed wire, and supported by entrepreneurs and industrialists, Americans filled in the frontier, that region of territory stretching west of the Mississippi River to the Pacific Ocean, by the end of the 19th century. The Lakota and other Plains tribes had first encountered American settlers as they pushed west in wagons on overland trails, but after the Civil War a rapid boom in railroad construction accelerated the process that exchanged Native American villages and hunting grounds for American farms, ranches, and towns.

The Railroad

The rapid western population growth that filled in the frontier could not have happened without the railroad. Only about 50,000 Americans migrated to the Southwest after westward trails were opened in the 1840s, but the floodgates opened when a westward railroad connection was completed in 1869 and migrants could ride the railroad westward (Hine & Faragher, 2007). In the 19th century the railroad symbolized American commercial and technological development. It was an icon of a new way of life and became a focus of some of the most eloquent writers of the day. In 1855 Walt Whitman, in Leaves of Grass, made this observation about the railroad in America:

I see over my own continent the Pacific railroad surmounting every barrier. I see continual trains of cars winding along the Platte carrying freight and passengers. I hear locomotives rushing and roaring, the shrill steam-whistle. I hear the echoes reverberate through the grandest scenery in the world. (Whitman, 2012)

The railroad also symbolized the new connectedness in America, since it united various parts of the nation like never before. The Transcontinental Railroad, constructed between 1863 and 1869, linked two major railroad construction projects, finally connecting the nation from east to west. Newly arrived immigrants, Chinese workers moving out of the mining fields, and large numbers of Mormons provided the bulk of the arduous labor required to clear land, lay track, and tunnel through mountains. By 1900 there were 200,000 miles of railroad track in the United States (White, 2012).

Railroad construction was difficult and exhausting, but many immigrant workers found it provided an opportunity to earn enough money to return to their homeland and live richly. Chinese railroad laborer We Wen Tan helped construct the railroad that moved eastward from California to Utah. He was present at the symbolic moment on May 10, 1869, when the Union Pacific and the Central Pacific Railroads met at Promontory Point in Utah. Upon its completion, he returned to his home village in China with the equivalent of $10,000, considered a fortune at the time. He built a large home and eventually sent his son to the United States (Chinese Railroad Workers in North America Project, 2014).

Homesteaders and Immigrant Farmers on the Great Plains

Another factor contributing to westward expansion was the Homestead Act. Passed by Congress in 1862 in the midst of the Civil War, the Homestead Act granted 160 acres of land in the public domain to any settler who lived on it for 5 years and improved it by building a house and plowing. The law reinforced the 19th-century belief in free labor (the notion that one could make free employment choice), and that the ownership of land defined American success. Proponents of the free labor ideology linked property ownership and hard work to independence and the rights of citizenship, and the terms of the Homestead Act enabled thousands of Americans to pursue these values.

The first settlers to take advantage of the Homestead Act had settled in the central and upper Midwest, where soil was rich and farming relatively easy. But by the late 1870s and 1880s, those seeking land were forced to look to the Great Plains, where arid soil, native grasses, and a harsh climate made earning a living off the land more difficult. In the short term the struggles of homesteading the Plains were eased by a multiyear wet cycle in the climate during these years. Above-average rainfall attracted thousands of farmers to settle in the region that had been called “The Great American Desert” just a generation before. In 1886, though, the cycle suddenly reversed. Drought lasted through the mid-1890s, driving half the populations of western Kansas and Nebraska to abandon their farms and move back east (Hine & Faragher, 2007).

Some homesteaders did succeed on the Plains, however. John Bakken, the son of Norwegian immigrants, moved with his family to Milton, North Dakota, to claim a plot of land. There he met and married Marget Axvig, a Norwegian immigrant, who helped him settle a homestead in Silvesta Township, North Dakota. Indeed, although western settlement and farming is often described as a male activity, women were essential to the success of homesteads and ranches. In addition to domestic work, western women often became entrepreneurs or worked for wages, providing capital needed for their own and their families’ survival. Women also played key roles in community building in the West, founding schools and other public institutions (Moynihan, Armitage, & Dichamp, 1998). John and Marget constructed a sod house, where they raised their two children, Tilda and Eddie. A colorized photograph of the family later became the basis of a postage stamp commemorating the Homestead Act.

Although taking advantage of the government land program was one way to populate the frontier, it was the railroads that were most active in the settlement of the Great Plains. Thanks to government grants issued to encourage their growth, western railroad lines controlled large tracts of land. Some settlers purchased land from the railroad in addition to claiming land under the federal homestead program. Railroad executives were eager to build settlement along their lines, and in doing so they increased the diversity of the region’s population.

Agents for some of the railroads enticed easterners and even European immigrants with offers of cheap land on credit and free transportation on the railroad line. Other railroads sponsored or organized settlements. One railroad company sent agents to Germany, where they recruited as many as 60,000 people to settle along the Santa Fe Railway line. Another railroad organized a company that established 16 settlements in Kansas and Colorado. The largest numbers of immigrants were of German extraction, but significant populations also came from Sweden, Norway, Finland, and Denmark. Other immigrants came on their own or in patterns of chain migration following family or other contacts. More than 2 million European immigrants located in the Great Plains between 1870 and 1900 (Hudson, 1985).

Farming on the Great Plains was hard work and required the cooperative effort of all family members. Fathers and sons did the heavy fieldwork of plowing, planting, and harvesting. Women grew vegetables, tended chickens, made butter and cheese, and preserved food for the winter months. Children were also expected to contribute to the household economy by participating in farming chores such as milking the cows or baling hay. As the farming economy grew more competitive, and farm size reduced due to repeated division among heirs, older children often left the farm to seek wage labor in urban areas, with the expectation that part of their wages would be used to help with family expenses. By the late 1880s American farmers had to respond to a multitude of changes in order to compete in the emerging national and global marketplace for agricultural products.

The Southwestern Frontier

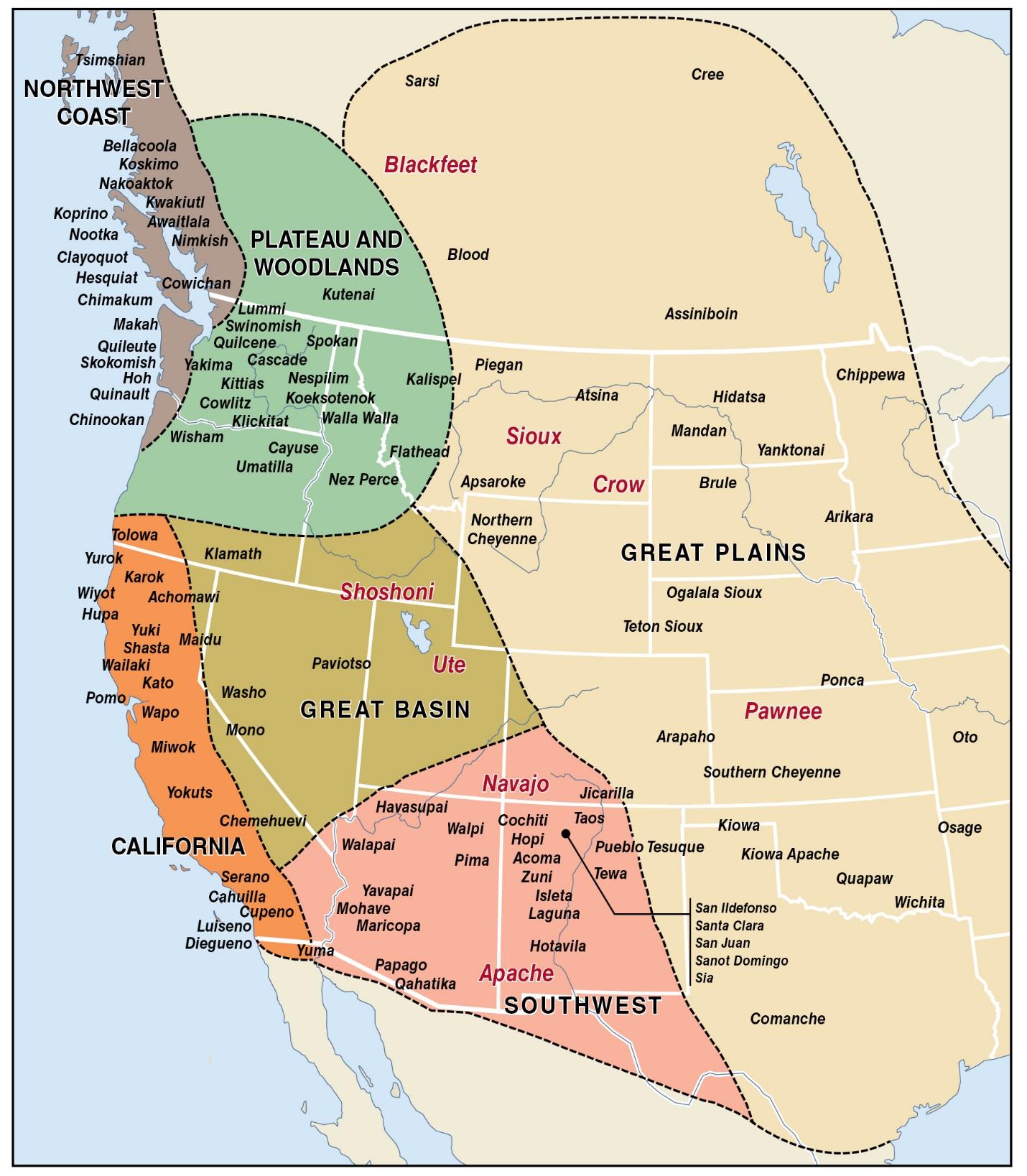

The southwestern frontier encompassed the states and territories that stretched along the 1,500-mile border with Mexico, including California, Arizona, New Mexico, and Texas, as well as Nevada, Utah, Wyoming, and Colorado (see Figure 1.1). Much of the territory had once been part of Spain’s colonial empire. Texas became part of the United States in 1845, and the United States annexed the rest of the region as part of the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, which ended the Mexican War of 1846 to 1848.

Figure 1.1: Map of the Southwest

American settlement encroached on the lands of the Native Americans of the Great Plains, Southwest, and Far West. Once the American frontier was officially closed in 1890, these native peoples lost their lands and strove to preserve their cultural traditions.

A map shows the boundaries of western expansion, along with Native American tribe names. There were six geographical areas of expansion: the Great Plains, the plateau and woodlands, the Northwest coast, California, the Great Basin, and the Southwest.

American expansionism encountered a mix of existing Latino and Native American cultures and societies in the Southwest. The Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo had transferred more than half of Mexico to the United States, and the Southwest remained a region that connected people and communities; migrants and trade moved fluidly between the two nations, establishing a pattern that persists well into the 21st century.

In Texas, ranching and staple crops such as cotton formed the economic base, and like residents of other former slave states, Texans struggled with the economic and social problems of the Reconstruction era. A highly stratified society elevated Americans and descendants of Spaniards, especially those with large landholdings, above the bulk of farm laborers, cowboys, and craft workers.

New Mexico’s inhabitants were more likely to be mestizo, a mix of Native American and Latino descent, who spoke Spanish and worshipped in the Roman Catholic Church. New Mexico, and to a certain degree Arizona, represented an area of the frontier where American and Native American cultures faced less direct conflict, and Native Americans there were not subjected to the federal land allotment policies that severely reduced the landholdings of Native Americans elsewhere in the West. Although the Pueblo tribes persisted in the Southwest, surviving as craft workers and sheep herders, in the spring of 1864 bands of the Navajo people endured what became known as the Long Walk, a forced deportation from their reservation in Arizona territory to Bosque Redondo in New Mexico. Forced to march up to 13 miles a day over an 18-day period, as many as 200 perished during the trek. The Native Americans of California did not fare well either; many had already lost their landholdings to Latinos during the territory’s years as part of New Spain and Mexico.

Latinos in the West

The Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo had granted Mexicans who chose to stay north of the new border U.S. citizenship. However, some people had difficulty adjusting. The Mexicans were originally farmers and herders, but soon the Americans—or Anglos, as they were called—began encroaching on their settlements in much the same way they had encroached on the lands of the Plains tribes. Federal policy at the end of the Mexican War guaranteed Latino residents’ land and property rights, but in practice Americans ignored these.

Unable to hold on to family lands, Latinos found it difficult to compete with Americans and were often relegated to unskilled manual labor. Significant numbers of Mexicans turned to migrant or seasonal farm labor for the first time. Many more, including women, moved to growing towns and cities, where they labored as seamsters or launderers (Daniel, 1981).

Some Mexicans organized to protest the new economic order that took away their lands and reduced employment opportunities, and sought to limit the damage to their communities and families. A New Mexico group ripped up railroad ties and other symbols of the new industrial farming order. Others protested more peacefully, calling for political action to protect their rights. Despite the cultural and economic changes, Latinos in the Southwest managed to preserve and extend their culture. Like the mestizos, most Latinos put their faith in the Catholic Church, but they worshipped with a distinct flair. Special religious days, including those celebrating Our Lady of Guadalupe and the Day of the Dead, remained important reminders of their traditional culture. Other Mexican national holidays, such as Cinco de Mayo (May 5) marking Mexico’s 1862 victory over the French, later expanded to become ubiquitous holidays celebrated across the United States.

Mormon Settlement

Another group of southwestern settlers that would clash with federal authorities, the Mormons, began settling in the Great Basin territory in the 1840s. The Mormons, members of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints, initiated settlements throughout what would become Utah, Idaho, western Colorado, and northern Arizona. The group formed in western New York in the 1830s but fled to Illinois and Missouri in an effort to escape persecution for their religious beliefs, which included polygamy (plural wives). After their founder and leader, Joseph Smith, was murdered, new leader Brigham Young led a large migration westward. In the Great Basin, the Mormons founded the state of Deseret, which eventually included 500 settlements.

Once Congress established Utah Territory in 1850, however, the Mormons clashed with federal authorities over their way of life. Newspaper accounts condemned them as sexual deviants for supporting plural marriage, even though only about 15% of Mormons actually practiced polygamy. A series of federal laws restricted the practice, and in 1879 the Supreme Court ruled against polygamy in the case of Reynolds v. United States. Upholding the Bill of Rights’ guarantee of religious freedom, the court ruled that the Mormons were free to believe in the principle of plural marriage, but it denied the legality of the actual practice.

Two additional laws further restricted their religion. The 1882 Edmunds Act restricted the voting rights of those practicing polygamy and imposed possible fines and jail penalties. The Edmunds–Tucker Act, passed in 1887, confiscated the major financial assets of the Mormon Church and also established a special federal election commission to oversee all elections in Utah Territory. With the frontier rapidly closing, the Mormons had nowhere else to flee. In the early 1890s the church officially renounced the practice of polygamy, and many prominent Mormon communities continued in Utah and other parts of the Great Basin (Eliason, 2001).

Asians in the West

In addition to Native Americans, Latinos, and Mormons, yet another group contributed to the rich social tapestry of the developing Southwest: immigrants from Asia, particularly China. This group was among the thousands of adventurous workers attracted to discoveries of gold and silver in the Southwest, particularly in California. Many citizens and immigrants traversed difficult overland trails to seek their fortune, attracted by the state’s explosive economic development. Between 1860 and 1890 approximately one third of California’s population was foreign born, making it one of the most diverse states in the nation. Immigrants hailing from the German states, Ireland, and Great Britain were common throughout the United States, but the Far West particularly attracted Chinese and other immigrants from Asia.

First arriving in the years surrounding the gold rush of 1849, more than 200,000 Chinese immigrants came to California in succeeding decades, where they soon accounted for almost 10% of the state’s population. The presence of the Chinese in America was part of a worldwide Asian migration driven by economic distress in their homelands caused by overpopulation and lack of employment opportunities.

Their anguish coincided with a desperate need for labor in the West, especially for railroad construction. Merchants and brokers in the United States arranged passage for the immigrants, almost always single men, who agreed to repay the debt they incurred from travel once they secured employment. Many men were recruited by a San Francisco–based confederation of Chinese merchants called the Chinese Six Companies, which acted as an employment agency and helped immigrants acclimate to the state’s social and economic systems. The few female immigrants worked as domestic servants or prostitutes (Takaki, 1990).

Chinese immigrants worked in the gold fields as laborers, cooks, and launderers until the fields played out, meaning no more gold could be extracted from them. Few were prosperous enough to stake a gold mining claim on their own. Unlike owning the land outright, a mining claim only gave the holder rights to extract the minerals below the surface. When railroad construction began in earnest, Chinese workers dominated crews on the Central Pacific, eventually accounting for the majority of the company’s employees. Many were specifically recruited to provide backbreaking pick and shovel labor constructing the railroad across the Sierra Nevada.

After 1869, when the Transcontinental Railroad was completed, the Chinese spread into the larger general labor pool. There they fell into competition with Latino and White laborers and faced considerable nativism and racism. White labor organizations campaigned against the use of Chinese labor, arguing that they drove down wages for American citizens. Violent clashes between American and Chinese workers became common, leading to anti-Chinese mobs in San Francisco in the late 1870s. A growing movement led by an Irish-born labor organizer named Denis Kearney lashed out with the slogan “The Chinese Must Go!” (as cited in Hagaman, 2004, p. 61).

Kearney’s followers formed the backbone of the anti-Chinese movement among White workers in Northern California. Kearney helped organize the Workingmen’s Party of California, the goal of which was to protect the place of White workers in American society. By 1878 Kearney was leading the charge against competition from inexpensive immigrant labor, and the Chinese specifically. He traveled as far as Boston to warn audiences about the potential competitive threat that inexpensive Asian labor posed to American workers.

The workers’ cries against Chinese competition developed a political component, and soon both the Democratic and Republican Parties in California demanded that Congress act to protect American workers against what some employers dubbed the “indispensable enemy” because of the key roles the Chinese immigrants played in western development (Saxton, 1995). The government responded in 1882 with the Chinese Exclusion Act, which banned the entrance of Chinese laborers for a span of 10 years. Renewed in 1892 and eventually made permanent in 1902, it effectively cut off the flow of Asian immigration into the United States until the middle of the 20th century.

1.2 The Western Economy

Agriculture drove the economic expansion of the trans-Mississippi West after 1865. Although gold rushes and mining booms initially attracted rushes of settlement, farming was the most common economic pursuit among westerners. The number of farms in the United States doubled between 1865 and 1900, with most of this growth coming from the expanding West. Homesteaders used the newly invented steel plow to break the tough grasslands of the Great Plains, shifting the nation’s breadbasket from New York’s Hudson River valley to the emerging settlements in the Midwest. In the Southwest and Far West, ranchers invested in herds of cattle to graze on natural grasslands and provide meat and dairy products to the nation. The railroads enabled these important changes, hauling cattle and grains to faraway markets and making it possible for farmers to produce more and compete in national and even global markets.

Ranching on the Open Range

Cattle ranching on the open range characterized parts of the Southwest, and especially the Great Plains. Ranchers purchased large herds of cattle, including the popular Texas longhorns, and set them to graze across vast expanses of open and largely unoccupied land. A mix of English and Spanish stock, the hearty longhorns’ numbers had increased exponentially during the Civil War. Armed with their namesake horns, they also required little protection against predators, making them easy to manage. Massive herds of cattle flourished, making the industry one of the most profitable in the West.

Ranching grew rapidly once railroads reached into the West. Way stations in Abilene, Kansas, shipped out 35,000 head of cattle after workers completed the Kansas Pacific Railway in 1867, and over the next 5 years ranchers shipped more than 1.5 million head of Texas longhorns from Abilene. Wichita and Dodge City, Kansas, grew up as market towns in competition with Abilene, and ranchers in the region increased the volume of western cattle transported by rail to distribution centers and slaughterhouses in faraway St. Louis and Chicago. Serving as the nation’s leading meatpacking city, as well as a central hub for east–west railroad lines, Chicago contained the massive Union Stock Yards, where workers could slaughter and process up to 21,000 cattle daily (Hine & Faragher, 2007).

Diversity characterized the ranching frontier. Cowboys, as seasonal migrant workers, were critical to the open range. They drove the herds of cattle as far as 1,500 miles for grazing and rounded them up for sale in the market towns. In return for a monthly salary of $25 to $40, payable at the end of the drive, cowboys worked from sunup to sundown and spent much of their time out in the open range with little in the way of shelter or other comforts. A diverse lot, White American cowboys were likely to work side by side with Native Americans, African Americans, and Latinos. Regardless of their ethnic background, cowboys tended to share camaraderie made necessary by a job that brought them together in the desolate conditions of the open cattle drive.

African American cowboys found opportunities in the West not available to them in the East. One of these men was Daniel W. Wallace, who began driving cattle as a teenager and ultimately purchased a 1,200-acre ranch in Texas that grazed 500 to 600 head of cattle. For more than 30 years, he remained a member of the White-dominated Texas and Southwestern Cattle Raisers Association. One of the most respected African American ranchers in the state, when he died in 1939, his estate was valued at more than $1 million (Earnest & Sance, 2010).

Closing of the Range

Cattle ranching grew more lucrative in the late 1870s and early 1880s, attracting eastern and even European investors, but the westward migration of settlers onto the Great Plains ultimately interfered with its expansive use of the open range. Settlers laid claim to or bought the land once open to all for grazing. Farmers raised fences to keep cattle out of their fields and tilled increasing swathes of the region’s grasslands on which ranchers depended to feed their growing herds.

Overstocking of cattle glutted the market, and weather-related disasters such as blizzards took a devastating toll on the industry in the mid-1880s. The massive herds depleted the native grasses as well, causing many cattle to die of starvation. The free-for-all of open range grazing fell by the wayside as more business-oriented techniques came into favor. Instead of cattle drives across hundreds of miles by lonesome cowboys, the industry concentrated herds on fixed ranches contained in fenced pastures and fed them a diet that consisted largely of grain (Kantor, 1998).

Mining the Frontier

California and the rest of the desert Southwest proved to be rich in mineral resources. The discovery of California gold in 1848 drew prospectors from the other parts of the United States, Europe, and Asia, all seeking to strike it rich. Between 1848 and 1852 the population of California grew from 14,000 to nearly a quarter million.

Mineral richness was not limited to California. Arizona held important deposits of copper, and Nevada was home to a massive silver deposit known as the Comstock Lode. The massive vein of silver Henry Comstock discovered along the Carson River sparked an influx of more than 10,000 miners seeking to make a fortune. Most were disappointed when they discovered that the silver lay deep underground, requiring a capital investment of $900,000 and the skill of engineers to drill some 3,000 feet underground to manage its extraction (James, 1998). Investors and mining corporations encouraged settlement of frontier towns, and when the railroad made transportation of goods and passengers possible, the shipping trade grew into its own important industry.

Mining Boomtowns

Mining towns blossomed overnight, employing ancillary agents as merchants and grocers. Saloons, dance halls, newspapers, and theaters were established to provide services and entertainment to miners and prospectors. In these boomtowns men outnumbered women, sometimes by as much as 10 to 1, and few arrived with their families in tow. Boardinghouses filled with single men, and theaters and amateur sporting events occupied the miners’ spare time. It was the saloon, however, that featured most famously in the leisure culture of the Far West. There miners mingled with ranch hands and gamblers to relax and socialize. Saloons served beer and whiskey, but they also provided food and limited lodging for travelers. Many saloons offered entertainment such as poker or other games of chance and also featured dancing women who sometimes doubled as prostitutes (Dixon, 2005).

The Mining Economy

By the 1870s control of the western mining industry was concentrated into the hands of a few wealthy men. Among them was George Hearst, who became rich through his investment in the Comstock Lode. Hearst later invested in the Homestake Mine located on former Lakota land in South Dakota’s Black Hills. It turned out to be the most productive gold mine of the era. Although some individuals continued to prospect on their own, the majority of miners worked for corporations.

Mining of gold and silver turned out to be short lived, and base minerals such as copper, ore, lead, and other heavy metals came to dominate the industry. Mining work was dangerous and difficult, and miners began organizing unions to demand better pay and safer working conditions. In 1893 the Western Federation of Miners organized, initially to prevent employers from using violence during workplace disputes. It eventually called for radical changes in the economic and social order. Within a few years the organization claimed more than 50,000 members and was the strongest labor organization in the West (Hine & Faragher, 2007).

The effects of the growing mining industry were felt beyond the fast urbanization of boomtowns. Cattle ranches in Southern California shipped meat to miners in the state’s northern counties. Inland valley farmers increased their production of wheat and other staple crops to feed the growing population. Easterners and immigrants began to take advantage of cheap land and earn their fortunes in agriculture. Irish immigrant James Irvine came to California with the gold rush, invested in land and merchandising, and eventually controlled the massive 120,000 acre Irvine Ranch, now the city of Irvine (Kyle, 1990). Concentration of land, mining, and industry quickly came to replace the free-for-all culture of the mining booms.

1.3 The Defeat of the Plains Tribes

The conquest of the West is as much a story of miners exploring and exposing gold and silver mines, or of cattle ranchers settling the western grasslands with their large herds, as it is of Whites displacing and conquering Native Americans.

At the end of the Civil War, nearly 250,000 Native Americans resided in the West. Southern tribes, including the Cherokee, Choctaw, and Chickasaw, had been forcibly moved to the Indian Territory (today’s state of Oklahoma) in the 1830s. Tribes like the Apache, Hopi, and Navajo, native to the Southwest, were destroyed or pushed into submission by the 1870s. By that time the largest segment of Native Americans (about two thirds of the population) resided on the Great Plains. Among them were Sitting Bull’s Lakota, the Cheyenne, the Arapaho, and the Comanche. Their defeat ensured American control of western territory, opening final areas of the frontier to American settlement and industrial expansion.

Plains Culture

Since acquiring the horse from the Spanish in the 17th century, the Plains tribes had lived a nomadic existence, traveling along with the buffalo herds on which they depended for food and other basic necessities of life. Using the horse to excel at hunting and warfare, Plains people were skilled fighters who proved to be formidable opponents of the U.S. Cavalry units sent to secure the West for American development.

Though they formed tribes with several thousand members, Plains tribes’ nomadic existence made division into smaller bands necessary. Within the Lakota tribe, for example, Sitting Bull’s band of Hunkpapa operated as an independent group with a chief and tribal council. Conflict among tribes was common, especially as the numbers of buffalo declined and bands competed for a scarce food supply.

Decline of the American Buffalo

The once numerous American buffalo herds were rapidly depleted by travelers and settlers, who often shot them for sport. This illustration shows White settlers shooting buffalo while riding on a train.

Before Europeans came to the eastern shores of North America, the continent swarmed with great dark herds of buffalo. By some estimates 30 million roamed the land. Once they began to use horses for hunting, which allowed the easy slaughter of more of the massive beasts, the Plains tribes depended on the buffalo for almost every element of their survival: food for eating, hides for clothing and shelter, bones for weapons and tools. According to one scholar, the buffalo not only was Native Americans’ chief source of food, it also “contributed vitally to the shape of their political and social institutions and spiritual beliefs” (Utley, 2003).

Several forces contributed to the decimation of the buffalo. In the late 1860s the Union Pacific Railroad split the great herd into a northern and southern half. To passengers on these trains, bored with the long journey, the herds of slow-moving buffalo became an entertaining diversion. Passengers with rifles often shot at the buffalo for sport, and the buffalo hunt and excursion was born.

In the early 1870s those working in tanneries on the East Coast realized that buffalo hides made excellent leather products. This sparked a wave of “hide hunters,” who were responsible for killing up to 3 million American buffalo a year. White hunters were not solely responsible for the destruction of the expansive herds. Once the market for buffalo hides grew, Native Americans accelerated their hunting with an aim to make a profit. They grew eager to participate in the national economy and engaged in a wide trade in buffalo hides. Within a short time the southern herd of American buffalo was almost completely extinct. Remarkably, in 1883 the United States sent a scientific expedition to the frontier; when the expedition returned home, its members reported that they could only find 200 buffalo in the entire western half of the United States. Some Americans spoke out against the killing of the buffalo, but their voices were in the minority.

Federal Native American Policy

The movement of American settlement into the West was accompanied by a continually changing relationship between the U.S. government and the Native Americans. Despite major cessions of tribal lands and multiple treaties guaranteeing their landholdings, pressure from White settlers prompted the federal government to renegotiate agreements and sometimes to take Native American lands by force.

The last 3 decades of the 19th century witnessed a final push to remove Native Americans from desirable land, concentrate their existence onto increasingly smaller plots, and urge their assimilation into the dominant White culture. While some tribes readily bowed to government pressure, others took up arms in a final effort to maintain cultural and political autonomy. Their resistance stood at odds with the federal government’s desire to extinguish tribal society through education, land policies, and federal law.

Expanding the Reservation System

A permanent policy of creating small reservations onto which individual tribes could be isolated and controlled gained prominence among federal policy makers. At a meeting in 1851, the U.S. government gave the leaders of the Plains tribes gifts and bounties in return for accepting these tribal limitations. The government gave the Dakota region north of the Platte River to the Lakota, the area west of the Powder River to the Crow, and the foothills of Colorado to the Cheyenne and Arapaho (Billington & Ridge, 2001). Advocates of the reservations hoped that the policy would help Native Americans assimilate into the larger mainstream culture of the United States.

The reservation areas included land that had limited agricultural use and was therefore of little interest to White settlers. The Bureau of Indian Affairs, the federal agency created in 1824 to oversee policies related to Native Americans, designated agents to tend to tribal needs (though agents had varying degrees of competence) and keep a watchful eye for any sign of hostility from the tribes. The agents promised the tribal chiefs that concentration onto these reservations was the best strategy because the lands would be theirs “forever.” Most agents were political appointees with little long-term interest in the Native Americans’ well-being, however. Corruption was rampant; some officials, for example, conspired with local ranchers to provide tribes with substandard rations and pocketed the profits.

The reservation policy ended the long history of treaties negotiated (and often ignored) between the federal government and individual tribes. Tribes were designated as “domestic dependent nations” instead of separate nations, subjecting members to federal and territorial laws. As a result, the tribes continued to be subject to federal regulation and oversight.

Diplomacy and the Wars on the Plains

The Plains tribes did not accept the evolving federal policies without objection; from the 1850s to the 1880s there was almost continual fighting. Often this would take the form of small raids, with 30 to 40 Native Americans attacking groups of settlers traveling west. Following the Civil War, the U.S. Army massed its forces in the West and attempted to subdue the Native American threat. Among these troops were four regiments of African American soldiers, nicknamed “Buffalo Soldiers” by their Native American adversaries.

However, despite the conflict, both sides also sought reconciliation. Red Cloud, another leader of the Lakota Sioux and one of the most fearsome foes the U.S. Army had faced, was one leader who pursued diplomacy (though he had doubts of its success). In 1870 the New York Times described Red Cloud as the “most celebrated warrior now living on the American Continent” (as cited in Lehman, 2010, p. 59) as he traveled to Washington, D.C., to give an eloquent speech before government officials. Red Cloud told the officials:

Look at me. . . . Whose voice was first sounded on this land—the red people with bows and arrows. The Great Father says he is good and kind to us. I can’t see it. I am good to his white people. From the word sent me I have come all the way to his house. My face is red, yours is white. The Great Spirit taught you to read and write but not me. . . . The white children have surrounded me and have left me nothing but an island. When we first had this land we were strong, now we are melting like snow on the hillside while you are growing like spring grass. (as cited in Lehman, 2010, p. 59)

Red Cloud had realized that the tribal traditional way of life could not continue among the growing numbers of Whites; thus, he urged his people to transition peacefully into the reservation system. His Washington trip underscored his willingness to work toward the reservation transition but also gave him the opportunity to seek resources such as badly needed farm implements and equipment. His outreach to the government angered Sitting Bull and other leaders of the Native American resistance and led to divisions that further weakened the tribes’ ability to resist.

Little Big Horn

Many Native Americans found life on their isolated reservations unfamiliar and longed for a return to traditional life. Diplomacy one moment led to violence the next, as demonstrated by the Battle of Little Big Horn in 1876. The conflict was sparked by the discovery of gold in the Black Hills of South Dakota, an area the Lakota and other tribes regarded as sacred. The lure of gold made Native American lands much more valuable to Whites, and President Ulysses S. Grant moved to declare the Black Hills region outside the Great Sioux Reservation. The U.S. Army established a presence of several thousand troops to check the increasingly hostile Native American tribes. Meanwhile, thousands of White prospectors, unwilling to wait for government action, swarmed the Native Americans’ land.

At the Battle of Little Big Horn in June 1875, warriors from the Lakota, Cheyenne, and Arapaho tribes defeated the Seventh Cavalry regiment and killed Lt. Col. George Armstrong Custer.

In 1876 Civil War hero Lt. Col. George Armstrong Custer and the Seventh Cavalry arrived to quell the uprising. One of the most skilled military men in the West, Custer had engaged in multiple conflicts with Native Americans beginning in 1866. His most notorious engagement occurred in November 1868 at the Washita River encampment of a group of Cheyenne. The location near present-day Cheyenne, Oklahoma, served as a winter camp for multiple Native American bands. Custer’s troops surrounded the camp and attacked at dawn, massacring dozens of men, women, and children. Hailed as an important victory in the Indian Wars, the attack enhanced Custer’s reputation but also established his reckless habit of charging into tribal encampments without fully assessing their numbers.

Applying similar logic at Little Big Horn, Custer found himself outnumbered and surrounded. In less than an hour, Native American warriors surrounded Custer and his men and killed more than 200 of them, including Custer. News of the event sparked fear and outrage in the American public. Within weeks army troops spread across the region, forcing the remaining Native Americans to surrender. Congress also attached a “sell or starve” provision to a pending Indian Appropriations Act. This stopped the shipment of much-needed food rations to the Sioux until they ceased hostilities and ceded the Black Hills to the U.S. government. The following year another agreement took the remaining Sioux lands and forced their relocation to reservations (Bruun & Crosby, 1999).

Chief Joseph and the Nez Percé Resistance

The forced confinement of Native Americans on faraway land in Indian Territory or on cramped reservation spaces sparked anger and terror among some tribal members. The Nez Percé, for example, occupied 17 million acres of valuable land in Montana, Idaho, Oregon, and Washington and had generally enjoyed cordial relations with settlers and federal officials. Interactions turned sour in the fall of 1877, however, when the U.S. government ordered the Nez Percé to move to a small reservation in Idaho Territory (Hine & Faragher, 2007). One of their leaders, Chief Joseph, refused to comply with this demand and decided the time had come not to fight, but simply to leave. He led 750 tribe members from their ancestral home in western Idaho toward potential safety in Canada. The journey lasted 4 months and covered more than 1,500 miles. The tribe members successfully evaded pursuit from the American frontier military, though not without some intense periods of fighting. Just 40 miles from the Canadian border, as the group prepared for its final leg from its camp in north-central Montana, the U.S. Army surrounded them and killed most of their leaders (Hampton, 2002). To prevent further death, Chief Joseph surrendered, saying:

I am tired of fighting. Our chiefs are killed; Looking Glass is dead. . . . The old men are all dead. It is the young men who say yes or no. He who led the young men is dead. It is cold and we have no blankets; the little children are freezing to death. My people, some of them, have run away to the hills and have no blankets, no food. No one knows where they are—perhaps freezing to death. I want to have time to look for my children and see how many I can find. Maybe I shall find them among the dead. Hear me, my chiefs! I am tired; my heart is sick and sad. From where the sun now stands, I will fight no more forever. (as cited in Cozzens, 2002)

In many ways Chief Joseph is representative of the larger cultural clash between the United States and the Native Americans. The advancing industrial technologies available to Americans, including the railroad and the telegraph, gave them an immediate advantage in pushing the tribes to the margins. Rapid industrialization and increasing White settlement could not be stopped by the declining numbers of Native Americans, no matter how hard they were willing to fight to preserve their land and traditions.

Geronimo and the End of War in the Southwest

Although the most dramatic conflicts between Native Americans and Whites occurred on the Great Plains, tribes in other western areas mounted strong resistance to the encroachment of American industrial society. The Apache wars were the culminating conflict that took place in the Southwest between 1878 and 1886. Geronimo, a former medicine man, was the leader of the Chiricahua tribe and one of the fiercest opponents of the Native American reservation policy. He made it his mission to resist the forced migration of his people to increasingly remote and inhospitable lands and waged his war throughout Arizona and New Mexico. The United States sent hundreds of soldiers to hunt him down. With each raid Geronimo’s forces dwindled, until he had just a handful left. In 1886 he surrendered, and the American government forced him to live the rest of his life on one of the reservations that he so detested (Kraft, 2000).

Assimilation and the Ghost Dance

While the military clashed with tribes in the Southwest and on the Great Plains, some reformers sought another path to appease Native American hostility and better integrate them into U.S. society. In an early push toward Americanization that would later characterize policies aimed at European immigrants, Congress passed the Dawes Severalty Act of 1887.

The law resulted in the complete “reorganization of Indian space and culture” (Greenwald, 2002). It divided tribal lands that were formerly held in common by the entire community into 160-acre plots for families and smaller plots for individuals. The Dawes Act also offered U.S. citizenship to Native Americans who accepted this so-called severalty and did not object to the division of tribal lands. Americans believed that dividing tribal land into privately owned parcels would transform Native Americans into citizens and farmers who shared White Americans’ values of free labor and capitalism.

The Lakota Sioux were among the first to be affected by the Dawes Act. Although many Sioux tried to engage in farming, they faced often insurmountable barriers. The severalties were located on arid lands where lack of rainfall made it difficult to produce marketable crops without expensive irrigation systems. Lacking the capital for even the most basic tools, many left their lands fallow, and the government reclaimed unplanted acreage. Arguing that the Sioux had consented to the severalty policy, the federal government opened “unused” portions of their lands to White settlement under the Homestead Act or simply sold the land to speculators. Sitting Bull and his followers stood by as their ancestral lands passed from their control with no arrangements for Native American families residing in the ceded areas (Hine & Faragher, 2007).

Many believed that in order to completely assimilate Native Americans into White American culture, their belief in communal ownership had to end—and that the Dawes Act could achieve this (Hauptman, 1995). As was the result of so many American policies directed toward Native Americans, however, the Dawes Act ended in failure. Instead of empowering tribal families as citizens, it established a new layer of governmental control in their lives and further limited freedoms on the reservations. Only a small percentage of Native Americans actually became farmers, while many more became dependent on the U.S. government for rations to survive.

Education was posited as another way to encourage Native people’s assimilation into White American society. Reformers established off-reservation boarding schools, especially for secondary education. Between 1880 and 1902, 25 such schools were established to educate between 20,000 and 30,000 Native American students. In addition to the basics, youth learned the English language, moral guidance, and vocational education. Although initially many families were coerced into placing their sons and daughters in the schools, over time some Native American families came to see these educational opportunities as a path to a viable future. For the poorest families, the schools were a means for their children to receive food and clothing and, hopefully, a chance at a better life (Stout, 2012).

After just 4 months at the Carlisle School, these Native American men were almost completely stripped of their heritage. Their hair and clothes were now styled like their White contemporaries, and they were taught to despise their culture.

The schools required a critical trade-off, however, because they suppressed or even denigrated traditional Native American practices and culture. Lone Wolf, a member of the Blackfoot tribe, recalled the initial shock of having his long braids, “the pride of all Indians” (as cited in Aitken, 2003, p. 98), snipped off and thrown on the floor upon his arrival at the Carlisle School. Typical Western-style pants and shirts replaced students’ native buckskin clothing. Merta Bercier, an Ojibwe student, recalled how she was taught to hate her culture: “Did I want to be an Indian? After looking at the pictures of Indians on the warpath—fighting, scalping women and children, and Oh! Such ugly faces. No! Indians were mean people—I’m glad I’m not an Indian, I thought” (as cited in Native American Public Telecommunications, 2006).

The Dawes Act and the assimilation movement spurred some Native Americans to engage in spiritual resistance. On New Year’s Day in 1889, for example, Wovoka, a Paiute prophet from Nevada, had a vision during a solar eclipse. He foresaw a time in the future when Native Americans would be reborn in freedom. He and his followers expressed joy through the performance of the Ghost Dance, a ceremony that lasted 5 days and included meditation and slow movements (Lesser, 1978).

The dancers yearned for the return of the buffalo and the retreat of the White settlers. The Ghost Dance celebrated traditional Native American culture and also promoted self-discipline, industriousness, and harmonious relations with Whites. However, government officials misunderstood it as a dangerous act of resistance. The ceremonies spread quickly through the tribal reservations, and, fearing a militant uprising, the U.S. government sought to squelch their messianic messages.

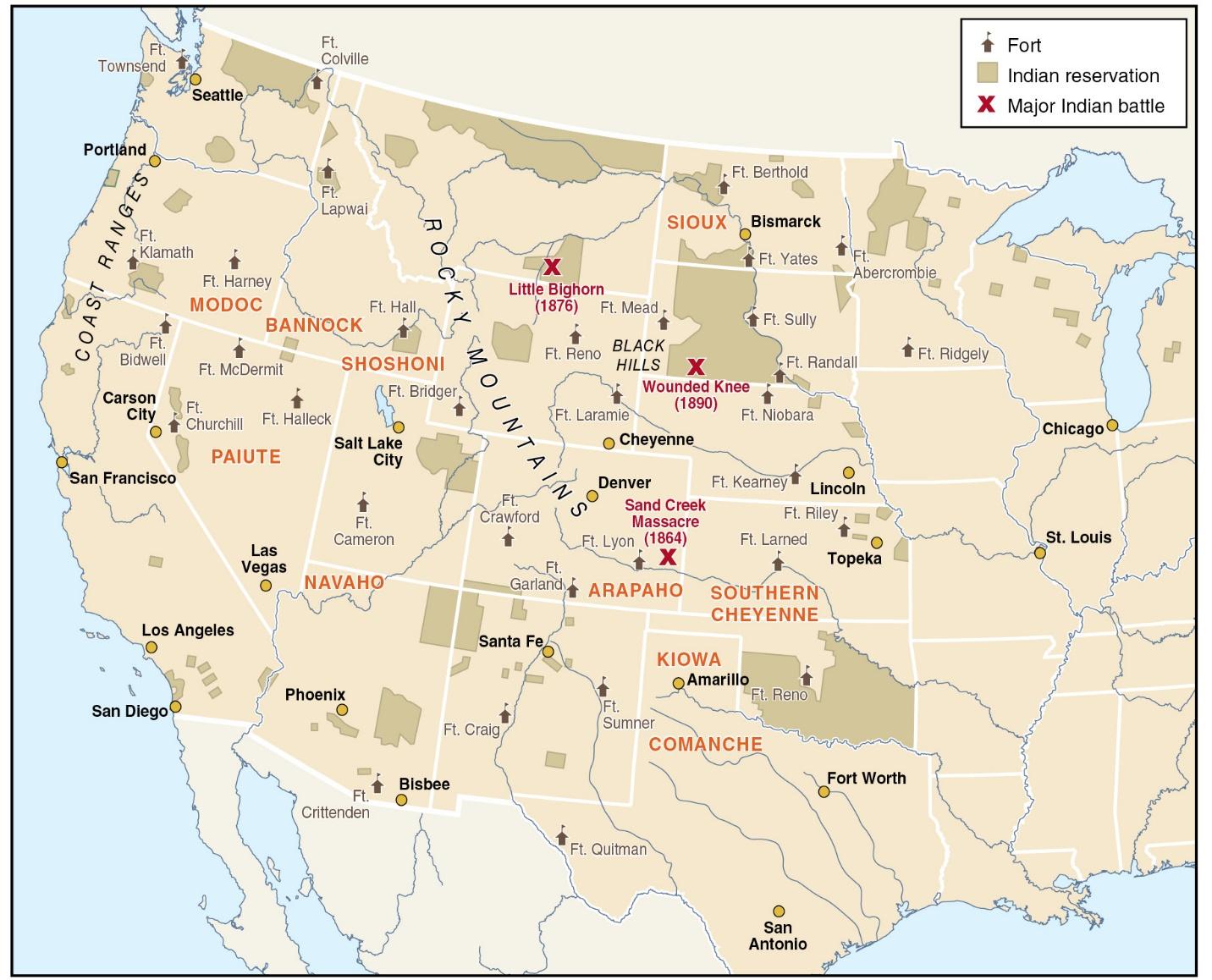

Two weeks after the death of Sitting Bull, the U.S. Army was called in to extinguish a particularly fervent Ghost Dance group that sparked alarm among nearby White residents, especially the reservation’s government agent. On the morning of December 29, 1890, at Wounded Knee Creek on the Lakota reservation in South Dakota, conflict between the Ghost Dancers and better armed military personnel resulted in a massacre of at least 250 Native Americans, many of whom were shot while fleeing. Native American bullets and crossfire from fellow military personnel felled more than two dozen U.S. soldiers. The Ghost Dances came to an end, and the Wounded Knee Massacre came to symbolize the end of frontier-era Native American resistance (see Figure 1.2) (Hittman & Lynch, 1998). The conflict that had stretched over more than 3 centuries lived on in cultural resistance, but the physical fighting ceased.

Figure 1.2: Native American Resistance

The original location of the various tribes of the Great Plains and Southwest appear here, along with major battles or conflicts between Native Americans and the U.S. Army.

A map of the major battles of the Native American resistance. The map also shows fort and reservation locations.

The “West” and the Frontier in American History

Exploring History through Film: Mythology of Buffalo Bill Cody

William "Buffalo Bill" Cody was a scout, buffalo hunter, and showman who is credited with popularizing the cowboy as an icon of the American West.

The death of Sitting Bull and the end of the Ghost Dance marked the cessation of Native American conflict and initiated a new chapter in the relationship between White Americans, Native Americans, and the ideal of the frontier and westward expansion. The idea of an exceptional and ever-expanding western frontier has long permeated American culture and was evident from the earliest European explorations of North America.

In 1890 the U.S. Census Bureau announced that because of the westward migration of Americans spanning more than 5 decades, it was no longer possible to find the “frontier” on a map of the United States because all land had been claimed or settled. This represented an important psychological and physical end to westward expansion. In his reflection on this startling pronouncement, in an article titled “The Significance of the Frontier in American History,” historian Frederick Jackson Turner (1893) declared the cultural significance of the American frontier to be its role as the “meeting point between civilization and savagery” (p. 3).

In his estimation the march of American settlement across the frontier was a triumph of national progress. In the late 19th century, most Americans agreed that conquering the frontier proved that their nation was exceptional and that the suppression of native cultures was natural and necessary to achieve that progress. Looking backward from the perspective of the 21st century, however, it is equally possible to identify the arrogance of a nation and the subjugation of native peoples that characterized colonial conquest.

By the late 19th century, the frontier continued to retain its mythic importance in American culture, largely because it represented the constant movement and changeability of the American spirit. According to prominent western historians, the West is about forward movement, about “getting there,” and the process of moving frontiers requires regular redefinition even today (Hine & Faragher, 2007).

American Lives: Andrew Carnegie

By the late 19th century, steel magnate and immigrant Andrew Carnegie was among the richest men in the world. His life story represents the ultimate rags-to-riches dream of success in America.

In March 1901 steel magnate Andrew Carnegie sold his vast business interests to industrialist and banker J. P. Morgan for a record $480 million. The sale made Carnegie, by some accounts, the richest man in the world, and it allowed Morgan to combine Carnegie’s holdings with his own to form U.S. Steel, the world’s first billion-dollar corporation.

Carnegie was born in Dunfermline, Scotland, in 1835. There his father was displaced from his skilled occupation as a hand weaver when textile mills mechanized cloth production. He brought the family to America in 1848, and after reaching Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, the Carnegies—Andrew, his brother Tom, and his parents—squeezed into two rooms a relative provided them free of rent.

Since it was not possible to follow his father in the weaving trade, Carnegie took a messenger’s job at a Pittsburgh telegraph office. His earnest work and resourcefulness caught the attention of Thomas A. Scott, a superintendent of the Pennsylvania Railroad, who hired him as his personal telegrapher and private secretary at a salary of $35 a month, about $750 in today’s dollars.

Carnegie parlayed the connections he made through Scott into a series of business investments, little by little accumulating enough capital to strike out on his own. He eventually settled on steel manufacturing as his primary focus. Locating his first plant outside Pittsburgh, Carnegie contributed significantly to the shift from skilled to unskilled labor in the steel industry. In many ways he was responsible for creating a situation very like the mechanized textile mills that had pushed his father to leave their homeland in search of new ways to support the family.

Immigrant workers from southern and eastern Europe were drawn to Carnegie’s mills, where they hoped to realize their own success in America. In reality, though, the drive for profit and increased productivity meant that workers at Carnegie Steel faced low pay and increasingly difficult and dangerous working conditions. The average unskilled steel mill worker toiled 12 hours a day in hot and dangerous conditions for less than $2 a shift, about $45 in today’s dollars. When transitioning from day to night turns, which happened twice a month, workers endured a 24-hour shift, followed by a day off. Few experienced any of the upward mobility that characterized their employer’s immigrant experience. Instead, Carnegie fought against the workers’ unionization attempts and did little to assist workers injured on the job.

Carnegie became emblematic of a number of industrialists who grew rich at the expense of their workers around the turn of the 20th century. Somewhat ironically, later in life Carnegie turned toward philanthropy. He established the Carnegie Corporation of New York and endowed nearly 3,000 libraries across the United States, Great Britain, and Canada. Many were located in the same communities as his steel mills, but few of his workers could enjoy the leisure of visiting a library. Giving away almost all his fortune, Carnegie spent his last years in a quest for world peace and harmony. He died in 1919 (Rau, 2006).

2.1 The Immigrants

Between 1877 and 1900 industrialization, urbanization, and immigration reshaped American society. In that period 12 million immigrants flooded into the United States seeking jobs, opportunities, and a better life. Millions of rural Americans abandoned the countryside to seek employment in the cities as well, especially once the mechanization of agriculture reduced the need for farm labor. Arriving in New York, Chicago, Pittsburgh, Birmingham, and other industrial centers, they found themselves amid a sea of unfamiliar faces from around the world.

Coming to America

Unlike earlier waves of immigrants from Ireland, England, Germany, and Scandinavia, many of these “new immigrants” hailed from areas of eastern and southern Europe, as well as from Asian countries like China and Japan. There the forces of industrialization, unemployment, food shortages, and forced military service served as push factors that sent millions across the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans. Among the earliest to arrive were thousands of Italians fleeing an 1887 cholera epidemic. Russian and Polish Jews sought refuge from anti-Semitic pogroms in the 1880s. The majority left their homelands after industrial pressures left them few job opportunities. So many immigrants arrived that by 1890 nearly 15% of the American population was foreign born (see Table 2.1).

Table 2.1: Immigration to the United States, 1860–1900

| Year | Foreign born | Total population | Percentage of total population foreign born |

| 1860 | 4,138,697 | 31,443,321 | 13.16% |

| 1870 | 5,567,229 | 38,558,371 | 14.44% |

| 1880 | 6,679,943 | 50,155,783 | 13.32% |

| 1890 | 9,249,547 | 62,662,250 | 14.76% |

| 1900 | 10,341,276 | 75,994,575 | 13.61% |

Just as economic and political factors served to push immigrants from their European and Asian communities, pull factors in America attracted them. Better and cheaper transportation made the transoceanic passage affordable to many, but it was the lure of work that most often figured into the decision to emigrate. Although industrialization was a worldwide phenomenon, the United States was quickly growing to be the world’s largest industrial employer. A combination of new technology, capital investment, and especially abundant natural resources helped support the rise of natural resource extraction and manufacturing.

Transnationalism also serves to explain the flow of immigrants into the United States in the late 19th century. The global flow of capital, ideas, and resources among countries made the industrializing United States the natural temporary destination for immigrants hoping to take what they earned and skills learned in the United States and use it to increase their resources and possibilities back in their homeland. Many of the earliest immigrants were young, single men who possessed few job skills. Particularly among Greeks and Italians, some single men came with no intention of staying in America permanently. Called birds of passage, they arrived in the United States aiming to earn enough money to purchase land or make a start in a trade or business once they returned to Europe. They used connections in American ethnic communities to find employment and lodging but funneled resources home.

A Judge magazine cover shows two boats dumping immigrants at the base of the Statue of Liberty.

The Art Archive at Art Resource, NY

Not everyone supported the idea of an immigration center on Ellis Island. This 1890 cover of Judge magazine shows immigrants being dumped at the base of the Statue of Liberty. Lady Liberty responds by saying, “If you are going to make this island a garbage heap, I am going back to France!”

Ellis Island

Europeans initially arrived at East Coast port cities, including Boston, New York, and Philadelphia. The largest number landed at New York Harbor, where they were processed at Castle Garden at the Battery in Lower Manhattan. Before long, however, the rising numbers of immigrants made it useful to establish federal control over and unify the process. The Immigration Act of 1891 shifted immigration regulation from the states to the federal government and established the Office of Immigration (later the Bureau of Immigration) to oversee the process. With the increased influx of immigrants, Congress saw the measure as an important means to secure federal oversight and control. It also established an inspection process that aimed to exclude undesirable immigrants. Those who were seriously sick, mentally ill, or likely to come under the public charge were to be returned to their homelands.

In 1892, in order to accommodate the rising numbers of immigrants, the Office of Immigration opened a receiving center on Ellis Island, 1 mile south of New York City and virtually in the shadow of the Statue of Liberty. The statue became an important symbol of hope for the new arrivals (Kraut, 2001). On it were words by poet Emma Lazarus that inspired many who came to America with the hope of a better life:

Give me your tired, your poor,

Your huddled masses yearning to breathe free,

The wretched refuse of your teeming shore.

Send these, the homeless, tempest-tossed to me,

I lift my lamp beside the golden door! (as cited in Young, 1995)

At Ellis Island, new arrivals passed through a medical examination and were questioned about their destination and economic status. For the majority of immigrants, the entire process took no more than 7 hours, after which they were permitted to pass into the city. Less than 1% of immigrants were rejected, but for those separated from family and denied their dream of coming to America (most often those from southern and eastern Europe), the processing center became known as the “Island of Tears.” Nearly 12 million immigrants were processed at Ellis Island between its opening in 1892 and 1954, when it closed permanently.

The Immigrant Experience

Once they passed through Ellis Island, immigrants experienced a life very different from what many had imagined. One Italian immigrant famously observed:

I came to America because I heard the streets were paved with gold. When I got here I found out three things: First, the streets weren’t paved with gold; second, they weren’t paved at all; and third, I was expected to pave them. (as cited in Puleo, 2007)

As more and more people immigrated to the United States, ethnic neighborhoods became common. Shown here is Little Italy in New York City around 1900.

Italians and other immigrants provided the labor for the growing industries and city construction. They built the New York subway system and worked 12-hour shifts in the steel mills of Pittsburgh and other northeastern cities. Many also worked as day laborers, launderers, and domestic servants.

The Italians, Poles, Hungarians, Russians, Greeks, Czechs, and others who came brought with them their own languages, lifestyles, and cultural traditions. Jews were most likely to emigrate in family groups, whereas many Irish arriving in the late 19th century were single women seeking employment as domestic servants. Although historians once believed that immigration was an alienating experience, more careful study has found that the new immigrants transplanted many facets of their former lives to their new homeland.

Immigrants’ cultural and ethnic values and experiences often determined their work patterns. Greeks, often birds of passage who planned to return to the Old World, took itinerant jobs on the railroads or other transient positions. Italians, whose culture valued much family time, preferred more sedentary and stable industrial work. Jews often operated as shopkeepers and peddlers or in the needle trades—occupations they transplanted from the Old World, where anti-Semitic regulations restricted their work choices. Some ethnicities, such as the Irish and Slovaks, encouraged women to work in domestic service, whereas others, including the Italians and Greeks, barred women from working outside the home (Gabaccia, 1995). Women in those groups often took in laundry or sewing work, and many cared for single young male immigrants who paid to board with established families.

Thousands traveled in patterns of chain migration, arriving in Pittsburgh or Buffalo to the welcome greetings of family or friends in an established ethnic neighborhood. In these tightly knit communities, new arrivals found many of the comforts of home, including newspapers in their native language, grocers specializing in familiar foods, and churches where their religious traditions were practiced. Many ethnic groups established self-help and benevolent societies. In New York City the Hebrew Immigrant Aid Society assisted Jews, and the Polish National Alliance and the Bohemian–American National Council aided those groups in their transition to American life. In larger cities immigrant communities established their own theaters and concert halls, as well as schools to educate their children (Bodnar, 1985).

In some cities tight-knit neighborhoods formed familiar cultural homes for multiple ethnic groups. In Pittsburgh, for example, the more than 12,000 Polish immigrants in that city in 1900 lived primarily in the Strip District, a narrow slice of land along the Allegheny River. There they found stores that catered to their food tastes and ethnic newspapers that reported news from Europe as well as from the local community. From this vantage point they could easily learn about job opportunities in many industrial shops, including Carnegie Steel. By the 1880s Pittsburgh’s Poles had established their own churches and begun to expand their neighborhood to the nearby hill district, still known by some as Polish Hill (Bodnar, Simon, & Weber, 1983).

Nativism and Anti-immigrant Sentiment

As ethnic communities grew and immigrants continued to transplant their cultures in America, a growing number of native-born Americans, especially White Protestants, grew concerned. Describing the new immigrants as distinct “races” from inferior civilizations, these nativists pointed to the newcomers’ cultural differences and willingness to work for low wages as causes for alarm. Some argued that they had inborn tendencies toward criminal behavior, and others claimed that the presence of so many foreigners threatened to make fundamental (and undesirable) changes in American society. As feelings of anti-immigrant sentiment increased, the “golden doorway of admission to the United States began to narrow” (Daniels, 2004).

The Chinese faced the most dramatic reaction. From the 1850s through 1870, thousands of Chinese entered the United States to work in western gold fields, on railroad construction, and in West Coast factories. Like their European counterparts in the East, Chinese immigrants built tightly knit ethnic communities to insulate themselves from personal and often violent attacks by nativists and to perpetuate their distinct culture. San Francisco’s growing Chinese quarter stretched six long blocks, from California Street to Broadway (Takaki, 1990).

In response to anti-Chinese concerns, in 1875 Congress passed legislation barring the entrance of Chinese women, and a total exclusion policy began to gain supporters. In the West a growing Workingmen’s Party movement, led by Denis Kearney, lashed out at Chinese laborers, claiming they unfairly competed with White American labor. Kearney delivered a series of impassioned anti-Chinese speeches, sparking violent attacks on San Francisco’s Asian citizens. Kearney was arrested in November 1877 for inciting a riot, but charges against him were subsequently dropped, and he continued his xenophobic campaign (Soennichsen, 2011).

As explained in Chapter 1, protests by Kearney and others led Congress to pass the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, which established a 10-year ban on all Chinese labor immigration. Although law already barred non-Whites from becoming naturalized citizens, this marked the first time that race was used to exclude an entire group’s entrance into the United States. Congress renewed the restriction after 10 years and made the exclusion permanent in 1902. It remained in effect until 1943.

Despite the ban, some Chinese did still enter the United States. Merchants, diplomats, and the sons of U.S. citizens were permitted to immigrate. A trade in falsified citizenship records also allowed many so-called paper sons to pass through the system. Jim Fong, who arrived in San Francisco in 1929 with forged documents, recalled enduring 3 weeks of interrogation by immigration officials before eventually being admitted as a U.S. citizen, despite the fact that he spoke no English. After working as a fruit picker and dishwasher, Fong studied English at night and eventually succeeded as a restaurant manager. Under an amnesty agreement, he relinquished his fraudulent citizenship in 1966 and eventually became a naturalized citizen (Kwok, 2014).

Other nativist groups waged less successful attempts at restriction during the 1890s. The Immigration Restriction League, formed in Boston in 1894, sought to bar illiterate people from entering America. Congress adopted a measure doing so in 1897, but President Grover Cleveland vetoed it. Another guise to restrict immigrant rights came in the form of the secret or “Australian” ballot widely adopted in the 1890s. It ostensibly aimed to protect voter privacy, but it also served to bar the illiterate from receiving help at polling places.

At the Angel Island immigration processing center, Chinese and Japanese immigrants were often detained for weeks or months and were subjected to interrogations like the one shown here.

As steam ships carrying immigrants entered New York Harbor, passengers leaned over the rails to stare at the Statue of Liberty standing tall and proud. When they rounded Liberty Island, the immigrants beheld another marvelous spectacle: the grandiose buildings that made up the Ellis Island processing station.

Welcoming its first immigrants in 1892, Ellis Island served as the nation’s busiest processing station until 1924, when immigration laws reduced the tide of European immigrants to a trickle. Before it closed in 1954, 12 million immigrants passed through its buildings into the United States. For the vast majority, the immigrant processing center was a quick stop on their way to building a new life in America.

After stepping off their ships, men, women, and children, most of them from Europe, stored their luggage in the baggage room and lined up for processing. When it was their turn, they entered the Great Hall with its massive vaulted ceiling and mosaic tiled walls and floor. Although a daunting experience, the overall atmosphere was one of welcome.

Exploring History through Film: Chinese Immigrants and Angel Island

Most Asian immigrants entered the U.S. through California's Angel Island. Unlike immigrants arriving at Ellis Island, those arriving at Angel Island met with severe restrictions and prejudice.

Asian immigrants arriving on the Pacific coast found a very different experience. The Chinese Exclusion Act greatly slowed but did not completely stop Chinese nationals from entering the United States. Beginning in the 1880s a significant number of Japanese also crossed the Pacific.

An immigrant station opened in 1910 on Angel Island in San Francisco Bay to process those arriving from Asia. In sharp contrast to the Great Hall and opulent buildings of Ellis Island, Asian immigrants arrived at a series of wooden barracks, where furnishings consisted of wooden tables and benches and metal bunks for sleeping. The Chinese faced the most intense nativism of any immigrant groups; officials determined to isolate Chinese newcomers, whom they feared might conspire with residents of San Francisco’s growing Chinatown to slip into the city illegally.

Instead of mere hours, immigrants landing at Angel Island were often detained for weeks or even months, and a higher number—between 11% and 30%—were returned to Asia (compared to fewer than 1% at Ellis Island). Some were questioned at length about their backgrounds and asked about subjects of which they had no knowledge. While confined under adverse conditions, many Chinese immigrants scrawled words and poems on the walls reflecting their experience. One immigrant wrote: “Everyone says travelling to North America is a pleasure, I suffered misery on the ship and sadness in the wooden building. After several interrogations, still I am not done. I sigh because my compatriots are being forcibly detained” (Kraut, 2001). After processing several hundred thousand immigrants, the Angel Island processing center closed in 1940.

2.2 The City

Before the Civil War, America’s total urban population stood at 6.2 million, and most American cities, with the exception of a handful of large urban areas, boasted populations only in the tens of thousands. Luring residents from small towns, farms, and foreign countries, American cities increasingly became home to individuals and families seeking employment in the growing numbers of factories and mills. By the turn of the 20th century, the United States counted 30 million urban residents, and six cities had populations reaching half a million. Three cities—New York, Chicago, and Philadelphia—were home to more than a million residents. By 1920 more Americans lived in urban areas than on farms, and the city was established as a dominant force in economic, social, and cultural life.

City Dwellers and Changing Demographics

The exponential growth of cities came largely from migration and immigration, with almost half of the influx originating from the American countryside. Falling farm prices and increased mechanization meant fewer rural opportunities. These largely working-class Americans joined millions of European immigrants seeking to better their lives in the cities.

Social class differentiated residential areas within the cities. In New York, with its central Wall Street financial center, middle- and upper-middle-class men and women traded and shopped at fancy retail stores and worked in newly constructed office buildings. Most middle-class residents moved their homes outside the city center to the fringes to avoid the growing number of ethnic and working-class neighborhoods that straddled the new industrial zones. Surrounding Wall Street were rings of tenements and apartment buildings where rural migrants, immigrants and the city’s poorest residents sometimes packed their entire families into a single room (Shrock, 2004).

The Changing Shape of the City

The city was a place of contrasts in the era that became known as the Gilded Age. This satirical term was coined by Mark Twain to describe the period of rapid urban and industrial change from 1877 to about 1900. In his 1873 novel, The Gilded Age: A Tale of Today, Twain described a glittering society with serious problems beneath the surface. A city skyline itself was evoked as a breathtaking symbol of progress, featuring new buildings that crept ever higher toward the heavens. In New York, for example, the Manhattan Life Insurance building towered over the city at nearly 350 feet. The city’s second largest building, the American Surety Building, stood 21 stories tall and 312 feet upon its completion in 1894 (Korom, 2013). It appeared that the technological wonders of these new places knew no bounds.

But for all the examples of progress in the American city, the tragic realities of poor living conditions, ethnic prejudice, and unfair working environments significantly tainted the urban experience for many. The American city was a paradox, a place that exemplified hope for the future while at the same time demonstrating the worst that life had to offer.

The Tenement

In addition to stunning new skyscrapers, Gilded Age builders tried new construction techniques to enable cities to house more workers and their families. Construction of the dumbbell tenement house, so named because of its distinctive shape, dominated between 1879 and 1901. Typically, these were very tightly packed structures with only a couple of feet between them. The entrance hallway was a long passage, sometimes less than 3 feet wide, that reached 60 feet to the back of the structure. Each floor was divided, with seven rooms on each side (see see Navigating History: Tenement Housing feature). Only four of these rooms on each floor had ventilation or were reached by sunlight.