HCA415 Community & Public Health-WK2-A1

5.1 Introduction

The previous chapters provided information on the basic concepts of community and public health; for example, history, definitions of terms, and epidemiology. Chapter 5 covers the broad topic of maternal, infant, and child health, including the health of teenagers. Infants, children, and teenagers are a demographically important group that forms a large percentage (nearly one-quarter of the total population) of the United States. In 2010, 74.2 million persons were under the age of 18 years (Howden & Mayer, 2011).

Healthy People 2020 states that

[t]he well-being of mothers, infants, and children determines the health of the next generation and can help predict future public health challenges for families, communities, and the medical care system. Moreover, healthy birth outcomes and early identification and treatment of health conditions among infants can prevent death or disability and enable children to reach their full potential. (HealthyPeople.gov, 2013b)

One of the crucial dimensions of maternal, infant, and child health is family planning and the empowerment of women regarding fertility and childbirth. This is the first topic discussed in the chapter. Significant community health issues associated with the unavailability of family planning services are high levels of infant mortality and mothers' inability to use prenatal health care services. Family planning services can help contribute to good birth outcomes as well as healthy babies and children. Unfortunately, limited availability of family planning services and low utilization of prenatal care can lead to infant mortality.

In comparison with many other developed countries, the United States ranks high with respect to infant mortality. In 2008, with respect to its infant mortality rate, this nation was in 28th position among a group of 31 of the world's developed nations (USDHHS, 2013). At that time, the U.S. infant mortality rate was more than twice the rate in Sweden, the country with the lowest rate. The respective figures were 6.6 per 1,000 (United States) versus 2.5 per 1,000 (Sweden).

What accounts for the low international standing of the United States with respect to infant mortality, and what are some of the causes of infant mortality? This chapter will point out that America faces many disparities in infant mortality across racial and economic divides. These disparities are reflected in the occurrence of adverse birth outcomes, such as preterm births, and infant deaths from causes such as sudden infant death syndrome.

Adverse birth outcomes are determinants of subsequent infant health. Factors associated with such outcomes are alcohol consumption, cigarette smoking, and prescription and nonprescription drug use during pregnancy. In addition to family planning, methods for reducing adverse birth outcomes include maternal health promotion through good nutrition, avoidance of smoking and alcohol consumption, breastfeeding during infancy, and provision of childcare to working mothers.

Photograph of a mother reading to her children.

Fotosearch/SuperStock

Mothers, infants, and children form the bedrock of community health. Their health ultimately determines what the future health of the community will look like.

Although the self-reported health of children in the United States tends to be at a high level—more than 80% of school-age children are in excellent or very good health—many children are afflicted with preventable infectious diseases, chronic diseases, and chronic conditions. Examples of chronic conditions that emerge during childhood are learning disabilities (e.g., Attention Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorders and Autism Spectrum Disorders). Also, a significant level of mortality from chronic diseases, preventable infectious diseases, and unintentional injuries occurs during childhood in the United States.

The teenage years are a time for new onset of chronic diseases and adoption of behaviorally linked disease risk conditions. Significant health issues for this group are teenage pregnancy, chronic diseases such as cancer, unintentional injuries, interpersonal violence, suicide, and conditions associated with an adverse lifestyle.

Healthy People 2020: Maternal, Infant, and Child Health—An Overview

Chapter 1 introduced Healthy People, which formulates a science-based strategy for improving our nation's health by the end of the 21st century. During the 3 decades since the beginning of Healthy People, three major publications (Healthy People 2000, Healthy People 2010, and Healthy People 2020) have presented goals for improving Americans' health. Healthy People 2020 objectives stress the importance of maternal and child health for the health of the nation (HealthyPeople.gov, 2012c). The goal of Healthy People 2020 in this arena is to: "Improve the health and well-being of women, infants, children, and families" (para. 2) The objectives of the maternal, infant, and child health topic area address a wide range of conditions, health behaviors, and health systems indicators that affect the health, wellness, and quality of life of women, children, and families. For more information, see Health Care in Action: Healthy People 2020: Summary of Objectives: Maternal, Infant, and Child Health.

Health Care in Action: Healthy People 2020: Summary of Objectives: Maternal, Infant, and Child Health

Number and Objective Short Title

Morbidity and Mortality

MICH–1 Fetal and infant deaths

MICH–2 Deaths among infants with Down syndrome

MICH–3 Child deaths

MICH–4 Adolescent and young adult deaths

MICH–5 Maternal deaths

MICH–6 Maternal illness and complications due to pregnancy

MICH–7 Cesarean births

MICH–8 Low birth weight and very low birth weight

MICH–9 Preterm births

Pregnancy Health and Behaviors

MICH–10 Prenatal care

MICH–11 Prenatal substance exposure

MICH–12 Childbirth classes

MICH–13 Weight gain during pregnancy

Preconception Health and Behaviors

MICH–14 Optimum folic acid levels

MICH–15 Low red blood-cell folate concentrations

MICH–16 Preconception care services and behaviors

MICH–17 Impaired fecundity

Postpartum Health and Behavior

MICH–18 Postpartum relapse of smoking

MICH–19 Postpartum care visit with a health worker

Infant Care

MICH–20 Infants put to sleep on their backs

MICH–21 Breastfeeding

MICH–22 Worksite lactation support programs

MICH–23 Formula supplementation in breastfed newborns

MICH–24 Lactation care in birthing facilities

Disability and Other Impairments

MICH–25 Fetal alcohol syndrome

MICH–26 Disorders diagnosed through newborn bloodspot screening

MICH–27 Birth weight of children with cerebral palsy

MICH–28 Neural tube defects

MICH–29 Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder and developmental delay screening

Health Services

MICH–30 Access to [a] medical home [a "home base" for medical care]

MICH–31 Care in family-centered, comprehensive, coordinated systems

MICH–32 Newborn bloodspot screening and follow-up testing

MICH–33 Very low birth weight infants born at level III hospitals

Source: Reprinted from HealthyPeople.gov. (2012d). Summary of objectives. Maternal, infant, and child health. Retrieved from http://www.HealthyPeople.gov/2020/topicsobjectives2020/pdfs/MaternalChildHealth.pdf

Maternal health refers to the health of women during pregnancy, childbirth, and the postpartum period (CDC, 2012l). The health of mothers is crucial to the overall health of the community and reflects the commitment of society to future generations. The key aspects of maternal health are family planning, the occurrence of maternal mortality and other adverse outcomes during pregnancy, and maternal health promotion. A trend in maternal health (perhaps in response to the growing number of births among older women) is an increasing number of cesarean births in the United States.

Family Planning

Healthy People 2020 states that "family planning is one of the 10 great public health achievements of the 20th century. The availability of family planning services allows individuals to achieve desired birth spacing and family size, and contributes to improved health outcomes for infants, children, women, and families." The goal of Healthy People 2020 with respect to family planning is to "[i]mprove pregnancy planning and spacing, and prevent unintended pregnancy" (HealthyPeople.gov, 2012b, para. 1 & 2). Healthy People 2020 lists the following activities as parts of family planning services:

Contraception and broader reproductive health services

Breast and pelvic examinations

Breast and cervical cancer screening

Sexually transmitted disease (STD) (more commonly known today as sexually transmitted infection [STI]) and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) counseling

Pregnancy diagnosis and counseling, and screening.

Photograph of a birth control pill container.

iStockphoto/Thinkstock

Family planning methods, such as providing education and access to birth control, seek to support individuals in creating the family they choose at a time that is best for them.

According to the World Health Organization, family planning is a method for helping people to have the desired number of children and for spacing births (WHO, 2012d). In less developed parts of the world, almost 250 million women who do not use any type of contraception would benefit from greater access to methods of family planning. The population growth of some developing countries exceeds the carrying capacity of the local area; more to the point, family planning can be helpful in bringing population in line with the Earth's carrying capacity, improving living conditions, and increasing economic development.

Family planning is essential to the health and autonomy of women, as well as for supporting the health and development of communities. From the world perspective, WHO cites the following advantages of family planning:

May help to prevent the transmission of sexually transmitted infections

Reduces the need for unsafe abortions

Contributes to the health and well-being of women

Aids in delaying pregnancies among very young women who are at risk of complications and death from childbearing

Helps to prevent pregnancies among older women, who are at high risk of complications.

Internationally, organizations such as the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation support access to family planning services. In the United States, Planned Parenthood and community-based organizations have been involved with family planning. Planned Parenthood provides reproductive health care to men, women, and teens (Planned Parenthood, 2013). A total of 73 Planned Parenthood affiliates are situated in local communities and are responsible for more than 750 health centers. Planned Parenthood indicates that "[t]hese health care centers provide a wide range of safe, reliable health care—and more than 90 percent is preventive, primary care, which helps prevent unintended pregnancies through contraception, reduce the spread of sexually transmitted infections, through testing and treatment, and screen for cervical and other cancers" (Planned Parenthood, 2013; Providing Trusted Community Health Care).

Additionally, The National Family Program was instituted in 1970 as part of Title X of the Public Health Service Act and is operated by the Office of Population Affairs (USDHHS, 2012). Funds from Title X support contraception (with the exception of abortion), family planning, and associated preventive health care. During 2011, Title X funding was awarded to 91 recipients (both public and private) located in the ten United States Department of Health and Human Services Areas. Examples of grantees were state and local health departments, nonprofit organizations, independent service providers, and agencies based in the community. The main grantees reallocated these funds to 1,142 subrecipients, creating a network of more than 4,000 family planning service sites. Programs funded under Title X served more than 5 million clients in 2011.

In order to provide health care services, public health programs utilize community health workers who are often on the front line of contact with members of the community. The Health Resources and Services administration reported that reproductive health concerns—sexually transmitted infections (such as HIV), prenatal care, and family planning—were among the issues covered most frequently by community health workers (Gold, 2010). Thus, community health workers are an important link in the chain of resources for family planning services, especially services for individuals from economically disadvantaged and immigrant communities.

Adverse Maternal Health Outcomes Associated With Pregnancy

Examples of adverse maternal health outcomes associated with pregnancy are maternal mortality and depression. Health promotion programs can aid in producing optimal health of pregnant women and their newborn infants. Healthy newborn children have an increased likelihood of progressing toward a healthy childhood and adolescence and becoming healthy adults. The definition of a pregnancy-related death is "the death of a woman while pregnant or within one year of pregnancy termination regardless of the duration or site of the pregnancy, from any cause related to or aggravated by the pregnancy or its management, but not from accidental or incidental causes" (CDC, 2012g, para. 1). Maternal mortality is considered a largely preventable condition and reflects the operation of environmental factors and the quality of health care. In less developed areas of the world, maternal mortality is many times higher than in wealthy countries.

Photograph of a pregnant Black woman sitting near a window.

Cusp/SuperStock

Marital status is just one of the factors linked to higher risk of maternal mortality among Black women. Statistically, single black women run a higher risk of maternal mortality than married white women.

Maternal Mortality (Pregnancy Associated Mortality)

Maternal mortality in the United States has been increasing during recent years. Although the reasons for this increase are not entirely clear, researchers have hypothesized that it may be associated with a number of factors. These are improved reporting systems for maternal mortality, the influence of a greater number of chronic conditions among pregnant women, adverse social conditions, lack of utilization of prenatal and postnatal care, and quality of care rendered during the birth process. For example, chronic diseases such as diabetes and hypertension can increase the risks of maternal mortality. In addition, pregnant women who do not receive any prenatal care or limited prenatal care have greater risks for undetected diseases and conditions that can also result in maternal mortality. A total of more than 70% of cases of maternal mortality can be attributed to the following seven causes: hemorrhage, thrombotic pulmonary embolism, infection, hypertensive disorders, cardiomyopathy, cardiovascular conditions, and noncardiovascular medical conditions (Berg et al., 2010). Figure 5.1 presents 10 leading causes of pregnancy-related death in the United States, for 2006–2008. The four leading causes shown in the figure were cardiovascular diseases, cardiomyopathy, noncardiovascular diseases, and hemorrhage.

The maternal mortality rate is defined as the number of deaths per 100,000 live births that are assigned to causes related to pregnancy. A total of 548 women died in the United States in 2007 from pregnancy-related causes (USDHHS, 2011); the highest rate (34.8 per 100,000) occurred among Black women. This rate has tended to increase in the United States during the past 2 decades. In 2007, the maternal mortality rate was 12.7 per 100,000 live births. This number represented approximately a twofold increase in comparison with 1987, when the rate was 6.6 per 100,000. The maternal mortality rate in California, the most populous state in this country, also showed an increasing trend. The rate for California (12.2 per 100,000 live births) between 2007 and 2009 was similar to the national rate for 2007 (California Department of Public Health, 2012). The Center for Family Health, Maternal, Child, and Adolescent Health located in the California Department of Public Health gives several possible explanations for this increase. These include "improved vital statistics data reporting, increasing prevalence of chronic conditions among pregnant women, worsening negative impact of social determinants of health, and quality of care issues in the prenatal period, at the time of labor and delivery, or in the postpartum period" (California Department of Public Health, 2012, p.1). The findings from the California Department of Public Health raise concerns about racial and social differences in maternal mortality.

There are substantial racial disparities in pregnancy-related mortality. The rate for Black women tends to be about three times the rate for White women (CDC, 2012g). The rates for the years 2006 and 2007 were as follows:

11.0 deaths per 100,000 live births for White women

34.8 deaths per 100,000 live births for Black women

15.7 deaths per 100,000 live births for women of other races.

In addition to race, factors associated with maternal mortality are older age of the mother, marital status, and not having access to prenatal care. Between 1998 and 2005, unmarried White women had a 40% higher level of maternal mortality than married White women (Berg et al., 2010).

Figure 5.1: Causes of pregnancy-related death in the United States, 2006–2008

A bar graph showing the percentage of pregnancy-related deaths caused by conditions such as cardiovascular disease, hemorrhage, and anesthesia complications, amongst other causes. Cardiovascular diseases and cardiomyopathy are the top causes of death, with 13.5 and 12.6% of the deaths, respectively. Hemorrhages, noncardiovascular disease, hypertension and other pregnancy disorders, infection, and thrombotic pulmonary embolisms each are responsible for about 11% of pregnancy-related deaths. Anesthesia complications rank the lowest, with 0.6% of the reported deaths.

Source: Adapted from CDC. Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/reproductivehealth/MaternalInfantHealth/Pregnancy-relatedMortality.htm

It is important for pregnant women to maintain a healthy lifestyle while pregnant, as well as seek consistent prenatal care, to prevent pregnancy-related conditions.

Depression During and After Pregnancy

Another health event that sometimes occurs during and after pregnancy is depression. This is a fairly common phenomenon that affects about one-twelfth of pregnant women (USDHHS, 2009a). A symptom of depression is feeling sadness and hopelessness during pregnancy. Possible causes of depression are a family history of depression, changes in brain chemistry, stress, and hormonal influences during pregnancy. Postpartum depression, a serious form of depression that occurs after childbirth, is believed to be associated with the rapid return of hormones to normal levels; treatment is imperative for postpartum depression. "Baby blues" are a milder and self-limited form of mood disturbance than postpartum depression. Affected women who do not seek treatment for serious depression can increase the risk of adverse effects upon their own health and the health and development of their fetus and newborn infant. Among the examples of harm to children linked to postpartum depression was the 2010 case of a South Carolina woman, Shaquan Duley, who confessed to drowning her two children in a river and was believed possibly to have been afflicted with postpartum depression.

Cesarean Births

Cesarean delivery (c-section) is "the delivery of the fetus by surgical incision through the abdominal wall and uterus (from the belief that Julius Caesar was delivered in this manner)" (The Free Dictionary, 2013). This method of delivery is regarded as major surgery. Some of the medical indications for cesarean delivery are "[r]epeat cesarean delivery, . . . [o]bstructive lesions in the lower genital tract, . . . [and p]elvic abnormalities" (Medscape Reference, 2011). Nonmedically indicated or elective cesarean delivery is a controversial topic with respect to its risks and benefits. A nonmedically indicated procedure in this instance is one that is not required for maintaining the health and safety of the mother or her fetus. The disadvantages of nonmedically indicated cesarean delivery are higher rates of complications, more frequent rehospitalization of mothers, and neonatal complications. Also, cesarean delivery is more costly than vaginal delivery.

Between 1996 and 2007, the rates of cesarean delivery increased by 53% from 21 per 100 to 32 per 100 births, or about one-third of all births in the United States (Menacker & Hamilton, 2010). The percentage in 2007 was the highest ever recorded up to that time. From 1996 to 2007, the rates of cesarean deliveries tended to increase with increasing age group. In 2007, the highest rates (48% of all births) occurred among women aged 40 to 54 years.

Often, there are specific medical indications for cesarean delivery. However, the increasing trend also is associated with nonmedical factors that include convenience in scheduling a birth (which is normally unpredictable), fear regarding the childbirth process, worry about possible physical damage caused by a vaginal delivery, and legal considerations (e.g., concerns about legal liability). For example, litigation could occur when a cesarean delivery might have prevented an adverse birth outcome.

Maternal Health Promotion and Prenatal Health Care

Health System Indicators

Dr. Novotny discusses infant and maternal health, and their importance in assessing the overall community health.

Critical Thinking Question:

How can assessing the public health help with chronic diseases, such as Diabetes or obesity? Research the maternal or infant health in your community — what do they indicate about the health of the area?

One of the highest priorities for maternal health promotion is the provision of prenatal care to all pregnant women. Prenatal care affords an opportunity to reduce the risks associated with pregnancy. Healthy People points out that

[t]he risk of maternal and infant mortality and pregnancy-related complications can be reduced by increasing access to quality preconception (before pregnancy), prenatal, and interconception (between pregnancies) care. Moreover, healthy birth outcomes and early identification and treatment of health conditions among infants can prevent death or disability and enable children to reach their full potential. (HealthyPeople.gov, 2012c, para. 5)

Healthy People states that "Pregnancy can provide an opportunity to identify existing health risks in women and to prevent future health problems for women and their children" (healthypeople.gov, 2012c, para. 3). The possible health risks to the pregnant woman and her fetus include a range of conditions such as high blood pressure and heart disease, diabetes, depression, genetically associated diseases, sexually transmitted infections (STIs), smoking, alcohol abuse, prescription and illicit drug use, poor nutrition, and unhealthy weight (HealthyPeople.gov, 2012c). One of the reasons for monitoring prescription and other drug use during pregnancy is the drugs' potential teratogenic effects. A teratogen is a substance that can cause abnormalities in the fetus.

Photograph of prebirth checkups at the Family Health and Birthing Center in Weslaco, Texas.

Karen Kasmauski/Science Faction/SuperStock

Regular prenatal checkups help to ensure the healthy growth of the fetus and continued health of the mother through pregnancy. This photo depicts volunteer midwives from the Family Health and Birthing Center in Weslaco, Texas who commit to about a year of work providing prenatal care to clients from lower income communities.

Prenatal Care

Prenatal care is the health care a woman receives while she is pregnant (USDHHS, 2009b). Important components of prenatal care are periodic visits to health care providers beginning with early pregnancy and maintenance of a healthy diet that provides adequate amounts of folic acid. Such care should begin early during pregnancy and continue on a regular basis in order to provide the greatest benefit. Prenatal care optimizes the health of the pregnant woman and that of her developing fetus. The former Surgeon General of the United States, C. Everett Koop, wrote about the need "to increase the public's understanding of health risks to pregnancy and to motivate pregnant women and women planning a pregnancy to take action to protect their health, obtain regular prenatal care, and seek other assistance when needed" (Koop, 1982).

Postpartum (Postnatal) Care

The term postpartum care refers to care given to new mothers after delivery of a child. Another term for postpartum care is postpregnancy health (United States National Library of Medicine, 2012). The postnatal period denotes the time interval that begins after birth and extends until about the first 6 weeks after birth. This time span is critical to the health and survival of a mother and her newborn. WHO notes that postnatal care is an effective means of preventing newborn deaths (WHO, 2012b). Nevertheless, worldwide, many babies are born outside of a hospital, and 70% of them do not receive any postnatal care.

Maternal and Child Nutrition

Maternal nutrition contributes to the development of healthy infants. During pregnancy, positive aspects of nutritional practices involve folic acid supplementation to prevent birth defects, avoidance of fish that contains mercury, and avoidance of exposures to environmental hazards. Exclusive breastfeeding of infants is a desirable practice that helps to protect the health of babies and benefits the health of mothers and society (USDHHS, 2010).

To reinforce optimal nutrition of infants, WIC encourages breastfeeding of infants. Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) is a special supplemental nutrition program designed for low-income women. The WIC program targets "low-income pregnant, postpartum and breastfeeding women, and infants and children up to age 5 who are found at nutrition risk" (United States Department of Agriculture [USDA], 2011, para. 1). Eligibility requirements vary according to family size and income. In order to be eligible for the program, an applicant's gross income must be at or below 185% of the U.S. poverty level. For example, during 2012 through 2013, that income level was $42,643 for a family of four persons (USDA, 2013).

Annually, federal grants to support the WIC program are awarded to states:

WIC is a Federal grant program for which Congress authorizes a specific amount of funding each year for program operations. The Food and Nutrition Service, which administers the program at the Federal level, provides these funds to WIC State agencies (State health departments or comparable agencies) to pay for WIC foods, nutrition education, breastfeeding promotion and support, and administrative costs. (USDA, 2012)

5.3 Health of Infants

Infant mortality has declined in the United States during much of the past half-century, but more recently has plateaued. The United States has relatively high infant mortality rates in comparison with other developed countries and needs to improve this unfortunate situation. Possible methods for reducing infant mortality are through the application of public health interventions that are known to be effective, and by focusing on racial and ethnic disparities. Many of these interventions need to be directed at improving health-related behaviors among pregnant women and increasing their utilization of prenatal care.

Infant Mortality

Infant mortality is defined as "the death of a baby before his or her first birthday" (CDC, 2012k). The death of an infant is a tragic event for parents and family members and a great loss for the community. This rare occurrence happens in about 6 out of 1,000 births in the United States. Nevertheless, given the large population of this country, approximately 25,000 infants die annually; the total number of infant deaths in 2009 was 26,412. Often, infant mortality is used as an indicator of the health status and social conditions prevailing in a country and for making international comparisons of the quality of health services.

Hemis.fr/SuperStock

Due, in part, to economic disparities among these groups, infant mortality rates in the United States are highest among American Indians/Alaska Natives and non-Hispanic Blacks.

Infant Mortality Rate

Data from the National Center for Health Statistics indicate that the infant mortality rate in the United States in 2011 was 6.05 infant deaths per 1,000 live births (MacDorman, Hoyert, & Mathews, 2013). Since 1940, the infant mortality rate has declined greatly, from almost 50 per 1,000 to slightly more than 6 per 1,000. Infant mortality rates have declined steadily since 1960 when there were 26.0 deaths per 1,000 live births to 6.9 per 1,000 live births in 2000. However, the infant mortality rate showed no decrement between 2000 and 2005 (MacDorman & Mathews, 2008). From 2005 to 2006 the rate again declined, leveled off between 2006 and 2007, and then continued to decline until 2011 (the year for which the latest data are available). As noted previously, the United States has a higher infant mortality rate than most other developed countries. Demographers theorize that among the factors related to the low ranking of the United States are social and economic disparities among ethnic and racial groups, especially among Blacks.

Infant Mortality Disparities and Sociodemographic Variations

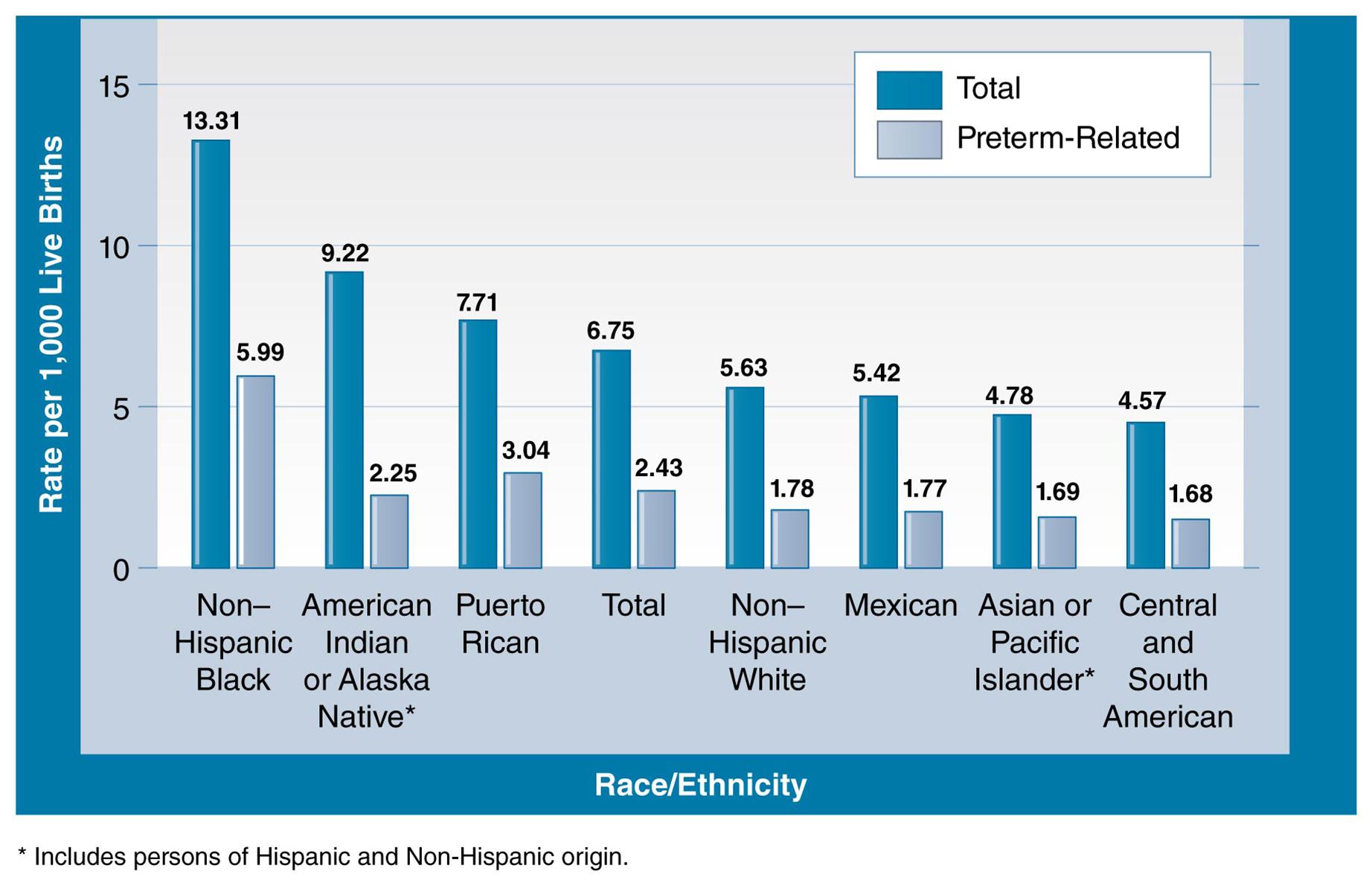

In the United States, marked disparities in infant mortality exist among racial and ethnic groups. Refer to Figure 5.2 for 2007 data on infant mortality rates by race and ethnicity of the mother. The figure shows that the rates were highest among non-Hispanic Blacks and American Indians/Alaska Natives and lowest among Asians/Pacific Islanders and persons of Central and South American origin (CDC, 2012n).

Figure 5.2: Total and preterm-related infant mortality rates by race and ethnicity of mother, United States, 2007

Source: Adapted from CDC. Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/reproductivehealth/MaternalInfantHealth/PretermBirth.htm

What might mothers in Central and South America be doing different that lowers their chances of preterm or total infant mortality? What might be affecting the rates of non-Hispanic Black infant mortality?

Data from the Office of Minority Health (OMH) indicate that infant mortality among Blacks is more than two times the rate among non-Hispanic Whites (USDHHS, 2012). In 2008, the infant mortality rate for non-Hispanic Whites was 5.6 per 1,000 live births; for non-Hispanic Blacks, the rate was 13.1 per 1,000 live births. The following facts regarding infant mortality in 2008 among Blacks are from the OMH:

Blacks had twice the sudden infant death syndrome mortality rate as non-Hispanic Whites.

Black mothers were 2.3 times more likely than non-Hispanic White mothers to begin prenatal care in the third trimester, or not receive prenatal care at all.

The infant mortality rate for Black mothers with over 13 years of education was almost 3 times that of non-Hispanic White mothers in 2005.

Other factors related to infant mortality in the United States include the state where the infant was born and maternal education and income (Heisler, 2012). In 2008, the four states with the highest infant mortality rates were Louisiana (9.1 per 1,000), Alabama (9.5 per 1,000), Mississippi (10.0 per 1,000), and South Dakota (8.4 per 1,000). The District of Columbia had a rate of 10.8 per 1,000. The states with the four lowest rates were New Hampshire (4.0 per 1,000), Vermont (4.6 per 1,000), Utah (4.8 per 1,000), and California and Massachusetts (both tied in fourth place with 5.1 per 1,000).

Higher levels of parental education and income are related to lower rates of infant mortality (Heisler, 2012). For example, rates of infant mortality are lower among mothers who have completed at least a high school education in comparison with those who have not completed high school. More educated women are more likely to attain higher income levels and engage in positive health behaviors such as avoidance of smoking during pregnancy. Also, women who have higher income levels usually have more access to health care services than those who have lower incomes.

According to the Office of Minority Health, promising strategies for reducing disparities in infant mortality include encouraging pregnant women to adopt healthful behaviors and lifestyles, to seek prenatal care, and to avoid practices that can affect birth outcomes adversely. For example, interventions might strive to improve pregnant women's nutritional status, increase their access to prenatal care early in pregnancy, and treat their chronic illnesses (CDC, 2012e). Other interventions might include programs for smoking cessation and avoidance of alcohol during pregnancy. As noted previously, cigarette smoking and alcohol consumption increase the risk of adverse birth outcomes.

Causes of Infant Mortality

The 10 leading causes of infant deaths in 2009 are shown in Table 5.1. About 20% of infant deaths were caused by congenital malformations and related conditions. The next highest percentage (about 17%) were associated with disorders related to short gestation and low birth weight. Sudden infant death syndrome caused 8.4% of infant mortality. Maternal complications of pregnancy and unintentional injuries caused 6.1% and 4.5% of infant deaths, respectively. The following sections will cover these five causes in more detail.

| Table 5.1: Number of infant deaths, percentage of total infant deaths, and infant mortality rates for 2009, United States | ||||

| Rank | Cause of death (based on ICD–10, 2004) | Number | Percent of total deaths | Rate |

| . . . | All causes | 26,412 | 100.0 | 639.4 |

| Congenital malformations, deformations, and chromosomal abnormalities | 5,319 | 20.1 | 128.8 | |

| Disorders related to short gestation and low birth weight, not elsewhere classified | 4,538 | 17.2 | 109.9 | |

| Sudden infant death syndrome | 2,226 | 8.4 | 53.9 | |

| Newborn affected by maternal complications of pregnancy | 1,608 | 6.1 | 38.9 | |

| Accidents (unintentional injuries) | 1,181 | 4.5 | 28.6 | |

| Newborn affected by complications of placenta, cord, and membranes | 1,064 | 4.0 | 25.8 | |

| Bacterial sepsis of newborn | 652 | 2.5 | 15.8 | |

| Respiratory distress of newborn | 595 | 2.3 | 14.4 | |

| Diseases of the circulatory system | 581 | 2.2 | 14.1 | |

| 10 | Neonatal hemorrhage | 517 | 2.0 | 12.5 |

| . . . | All other causes | 8,131 | 30.8 | 196.8 |

| Rates are infant deaths per 100,000 live births. | ||||

Design Pics/SuperStock

Down syndrome is one of the congenital malformations leading the causes of infant mortality in the United States.

Congenital Malformations

In 2009, congenital malformations were the leading cause of infant mortality in the nation. A congenital malformation is

[a] physical defect present in a baby at birth but can involve many different parts of the body, including the brain, heart, lungs, liver, bones, and intestinaltract. [A] [c]ongenital malformation can be genetic, it can result from exposure of the fetus to a malforming agent (such as alcohol), or it can be of unknown origin. (MedicineNet.com, 2012)

Among the types of congenital malformations are Down syndrome, heart defects, limb deformities, cleft palate, and neural tube defects. Infectious diseases (e.g., German measles) and environmental exposures can cause congenital malformations. Serious congenital malformations can produce long-term disabilities and devastating impacts upon the affected person, families, and society.

Low Birth Weight

Low birth weight is the term used to describe a birth weight of less than 2,500 grams (about 5.5 pounds) (CDC, 2009). In 2009, low birth weight was among the second leading causes of infant mortality. Low birth weight is a risk factor for several types of health problems including neurodevelopmental disabilities and inspiratory illnesses. Variables associated with low birth weight are described later in the chapter.

Preterm (Premature Births)

The definition of preterm (premature) birth "is the birth of an infant prior to 37 weeks gestation" (CDC, 2012n). Fetuses born before the full gestation period have a greater risk of complications than full-term infants. Slightly more than 12% of births (500,000 births) in the United States are preterm births. They are significant for community health because of their association with infant death and long-term neurological disabilities including cerebral palsy among children. The risk of adverse health outcomes associated with preterm births increases with shorter gestation periods; such outcomes can occur even among infants who are slightly preterm. Another aspect of preterm births is racial and ethnic disparities in their occurrence. The highest rates occur among Black women and the lowest among Asian or Pacific Islander women (Institute of Medicine, 2006).

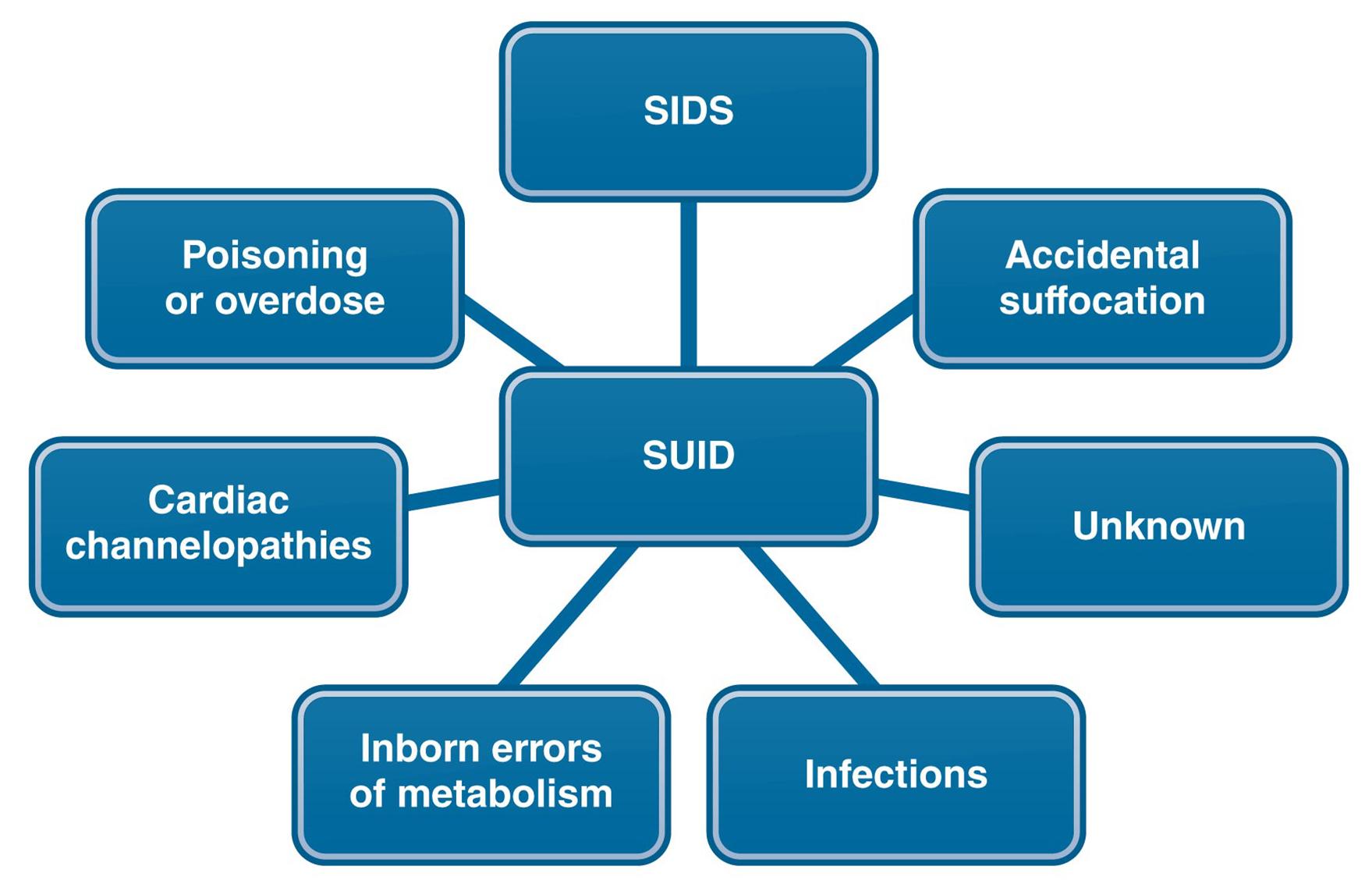

Sudden Unexpected Infant Death/Sudden Infant Death Syndrome

Sudden unexpected infant deaths (SUIDs) are defined as "deaths in infants less than one year of age that occur suddenly and unexpectedly, and whose cause of death are not immediately obvious prior to investigation" (2012q). Figure 5.3 shows six causes plus a category of unknown causes of SUID in the United States. Sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS) is one of the component causes of SUID and is responsible for about half of cases of SUID. Other causes of SUID shown in the figure include poisoning, suffocation, and infections.

Figure 5.3: Sudden unexpected infant death syndrome (SUID)

Many of the known causes of SUID can be prevented. How can public health professionals help protect infants?

Sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS) refers to "the sudden death of an infant less than 1 year of age that cannot be explained after a thorough investigation is conducted, including a complete autopsy, examination of the death scene, and review of the clinical history" (CDC, 2012q). Thus, a distinguishing characteristic of a death from SIDS is that no cause can be found even after an autopsy has been performed. SIDS is the third leading cause of infant mortality in the United States.

Maternal Risk Factors for Adverse Birth Outcomes

Healthy mothers tend to produce healthy infants. However, a mother's health, when unsatisfactory, is associated with adverse birth outcomes such as fetal and infant mortality. The mother's health is a determinant of her infant's morbidity, disability, impairments, and congenital malformations. In advance of becoming pregnant, women can improve the health of their infants through maintaining good nutrition, control of chronic diseases, and establishment of a healthy lifestyle that includes avoidance of risk factors for pregnancy complications. Older women have an increased risk of giving birth to an infant with Down syndrome. Other examples of maternal risk factors are provided in Table 5.2.

| Table 5.2: Examples of selected maternal risk factors for adverse birth outcomes | |

| Diabetes | Alcohol consumption |

| Hypertension | Cigarette smoking |

| Heart disease | Sexually transmitted diseases |

| Older maternal age | Prescription and nonprescription drugs |

| Poor maternal nutrition | Infectious diseases |

| Maternal obesity | Exposures to environmental toxins |

Diabetes

A form of diabetes known as gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) is associated with pregnancy. GDM, an impairment of the body's capability for processing carbohydrates, causes an increase in blood glucose levels. GDM affects from 2% to 10% of pregnant women (CDC, 2012d). In most cases, the condition resolves after delivery, but GDM is associated with the onset of diabetes among some women following pregnancy. Persistently high blood sugar among women with GDM increases the likelihood of preeclampsia, which is characterized by hypertension, protein in urine, and edema. Other outcomes of GDM are preterm births and the need for cesarean births. Pregnant women who have preexisting diabetes (type I or type II) can experience the triggering or exacerbation of health issues including hypertension, heart disease, and blindness. Pregnant diabetic women whose blood sugar continues to be elevated have increased risks of miscarriage, stillbirths, and other adverse birth outcomes.

Hypertension/Cardiovascular Disease

Potential effects of maternal hypertension upon the fetus are infant death, preterm delivery, and small size for gestational age. For the pregnant woman, hypertension is related to risk of maternal complications from preeclampsia and gestational diabetes, and placental abruption (CDC, 2011d). During a normal birth, the baby is born first, and then a few minutes later the placenta separates from the uterus and is expelled from the body; when placental abruption occurs during delivery, the placenta separates from the wall of the uterus before a baby is born. Severe maternal hemorrhaging can result.

Maternal Obesity

As the prevalence of obesity has increased in this country, obesity among pregnant women also has become increasingly common. Obesity during pregnancy occurs among approximately 20% of pregnant women (CDC, 2012m). Obesity increases the risk of several important complications during pregnancy, including:

Gestational diabetes

Hypertension

Preeclampsia

Need for cesarean section.

Alcohol Consumption During Pregnancy

Pregnant women and sexually active women who are not using contraception should not consume alcohol. The CDC states that "there is no known safe amount of alcohol to drink while pregnant. There is also no safe time during pregnancy to drink and no safe kind of alcohol. CDC urges pregnant women not to drink alcohol any time during their pregnancy" (CDC, 2010b). Refer to Health Care in Action: Pregnancy and Alcohol Consumption for the U.S. Surgeon General's statement on alcohol.

Health Care in Action: Pregnancy and Alcohol Consumption

Based on the current, best science available, we now know the following:

Alcohol consumed during pregnancy increases the risk of alcohol-related birth defects, including growth deficiencies, facial abnormalities, central nervous system impairment, behavioral disorders, and impaired intellectual development.

No amount of alcohol consumption can be considered safe during pregnancy.

Alcohol can damage a fetus at any stage of pregnancy. Damage can occur in the earliest weeks of pregnancy, even before a woman knows she is pregnant.

The cognitive deficits and behavioral problems resulting from prenatal alcohol exposure are lifelong.

Alcohol-related birth defects are completely preventable.

Source: CDC. (2005). Advisory on Alcohol Use in Pregnancy. A 2005 message to women from the U.S. Surgeon General. Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/fasd/documents/sg-advisory.pdf

Fetal alcohol spectrum disorders (FASDs) are an example of a condition that can affect children born to mothers who consumed alcohol during pregnancy. FASDs cause abnormalities of the face and body structure, low body weight, and behavioral and intellectual deficits.

CARDOSO/BSIP/SuperStock

According to the CDC, no amount of alcohol is safe to drink while pregnant.

Maternal Tobacco Use During Pregnancy

Cigarette smoking during pregnancy increases the risk for a group of severe health problems among fetuses and newborn infants. Among the risks that pregnant women incur when they smoke are lowered fertility, miscarriage, placental abruption, preterm birth, SIDS, certain birth defects (e.g., cleft lip or cleft palate deformity), and infant death (CDC, 2012o). Despite these adverse consequences, about 13% of women in the United States smoke during the last 3 months of pregnancy. In addition to cigarette smoking, a pregnant woman's exposure to secondhand cigarette smoke is also harmful. One of the possible adverse effects of secondhand cigarette exposure is low birth weight.

Sexually Transmitted Infections

Sexually transmitted infections can cause serious consequences for the developing fetus and newborn (CDC, 2011e). Spread of infections from mother to fetus or newborn is called vertical transmission. Among pregnant women, the four most common STIs and their approximate numbers of cases, respectively, are bacterial vaginosis (1,080,000), genital herpes simplex virus 2 (880,000), trichomoniasis (124,000), and chlamydia (100,000). Some of the risks of STIs during pregnancy are infection of the fetus while in utero, transmission of the STI to the newborn during delivery, stillbirths, low birth weight, and neonatal sepsis.

HIV, another STI, can be passed from mother to fetus during pregnancy, from mother to newborn during delivery, and from mother to infant during breastfeeding. Risk factors for vertical transmission of HIV include exposure of the fetus to HIV while in utero and to mother's blood and bodily secretions during birth. Also, breast milk from mothers infected with the HIV virus can transmit the virus to breastfed infants (Buchanan & Cunningham, 2009). At present, the possibility of vertical transmission of HIV is increased among pregnant women who are not tested for HIV. Often, pregnant women are not tested on a timely basis because they do not receive prenatal care.

Infectious Diseases

When a pregnant woman has acquired an infectious disease and this disease crosses the placental barrier to infect the fetus, it is called a congenital infection. The common types of these infections are described by the acronym TORCH (About.com, 2009), which stands for:

Toxoplasmosis

Other infections (e.g., chickenpox)

Rubella

Cytomegalovirus

Herpes simplex virus

For example, chickenpox and rubella (German measles) are vaccine preventable diseases that can cause birth defects when they infect the fetus.

Environmental Toxins

Environmental chemicals and toxins are linked to adverse birth outcomes. Examples of potentially hazardous substances and exposures are prescription and nonprescription drugs, heavy metals (e.g., lead and mercury) present in the residential environment and food, pesticides, industrial chemicals, and ionizing radiation from x-rays and naturally occurring sources. More information on this topic is presented in Chapter 7.

5.4 Children

This section

information on the health status of children in the age ranges of early childhood (1 to 4 years—toddler and preschool ages) and school age (5 to 11 years—middle childhood). According to the CDC, a total of 82.2% of school-age children have excellent or very good health status.

Fancy Collection/SuperStock

Individuals begin to develop the skills they need to live healthfully early in life. The development of healthy habits, like exercise, starts during childhood.

The period of early childhood is important because it is during this time that children develop habits and behaviors that impact their health throughout their lifespan (CDC, 2011c; CDC, 2012f; CDC, 2011b). Desirable lifestyle practices such as consumption of healthful foods, participation in vigorous exercise, and avoidance of substances (tobacco, drugs, and alcohol) are established and reinforced during the school-age years. Much work needs to be done to encourage children to consume a healthy diet, as 20% of school-age children during 2007 and 2008 were obese.

The discourse on the health of children should include the role of fathers in addition to the importance of mothers in promoting the health of children. Fathers who have positive relationships with the mothers of their children are likely to contribute to the development of children who are psychologically healthy, emotionally secure, and who perform well in school (Rosenberg and Wilcox, 2006). Effective fatherhood involves devoting time to children, making sure that their material needs are met, and being a good role model.

The next sections assess trends in child mortality and morbidity. From the international perspective, child mortality continues to be at unacceptably high levels as a result of the impact of malnutrition and infectious diseases. In this country, unintentional injuries are the leading cause of child mortality. Among the most frequent causes of morbidity in America are infectious diseases, asthma, and developmental disabilities.

Mortality Among Children

Stressing the global point of view, WHO indicates that levels of child mortality continue to be unacceptably high, especially in less developed areas. Developed countries have a somewhat more favorable child mortality profile. In the United States, mortality reaches its lowest level among children, and then increases as persons grow older. Child mortality is highly preventable and can be reduced greatly through improvement of environmental conditions and hygiene levels, as well as increased parental compliance with immunizations for vaccine preventable diseases.

International Trends in Child Mortality

The number of deaths among children remains high even though progress in reducing child mortality has been made since 1990. WHO provides worldwide information on the leading causes of death and the percentage of deaths among children younger than 5 years of age. In 2011, globally, there were a total of 6.9 million deaths among children under the age of 5. Many of these deaths were caused by preventable or easily treatable conditions or by malnutrition (WHO, 2012c; WHO, 2012a). The leading causes of death were pneumonia (18%), preterm birth complications (14%), diarrhea (11%), birth asphyxia (9%), malaria (7%), and all other causes (41%). Almost three-quarters of the child deaths happened in Africa and Southeast Asia.

Approximately 20 million of the world's children were afflicted with severe malnutrition in 2010. WHO advocates exclusive breastfeeding of infants as a method for improving the nutritional status of children and preventing childhood diarrhea and respiratory infections.

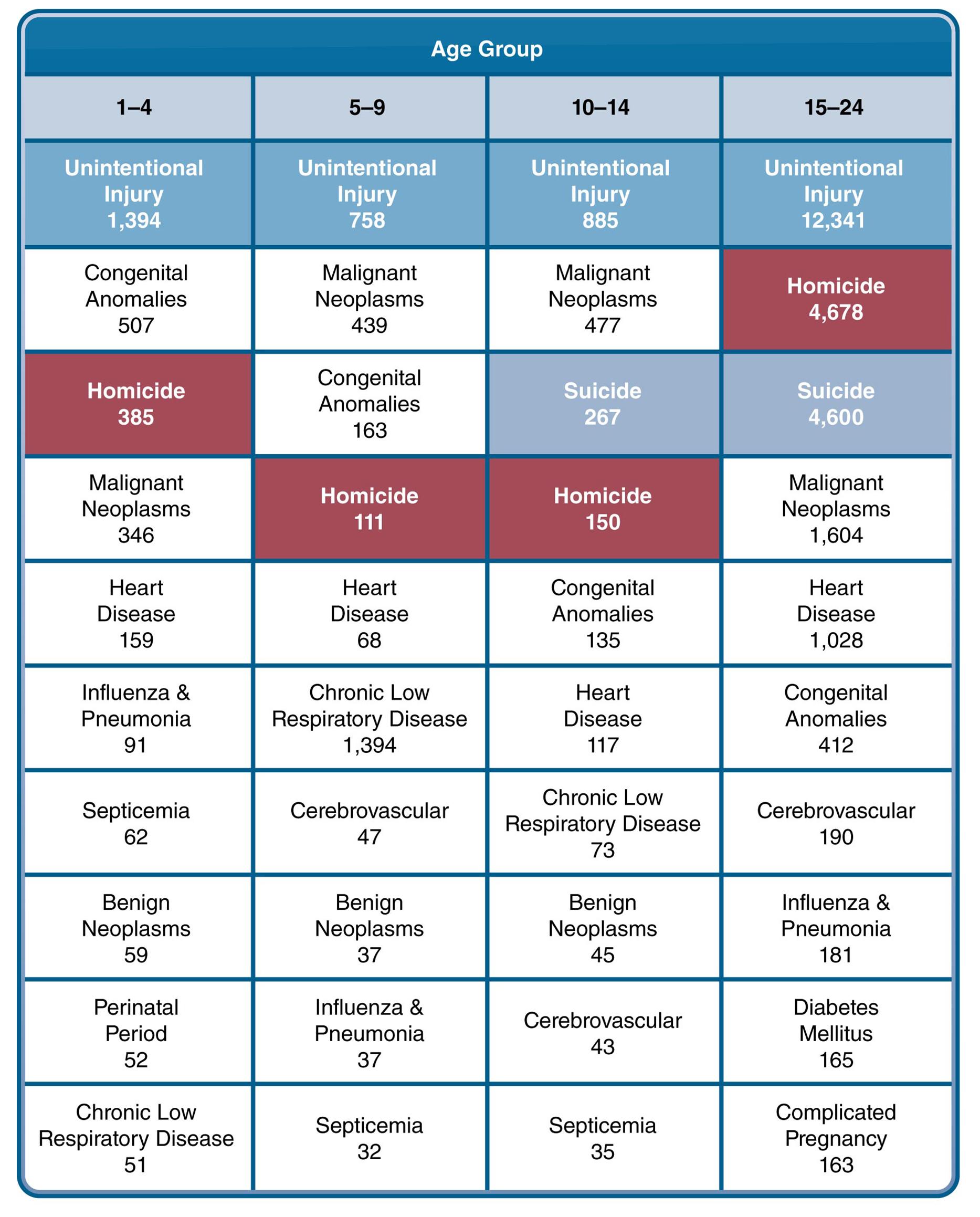

Leading Causes of Children's Deaths in the United States

With respect to the United States in 2010, Figure 5.4 shows the leading causes of children's death for three age groups of children: 1 through 4, 5 through 9, and 10 through 14. In all three age groups, unintentional injuries were the leading cause of death (CDC, 2012t). Among toddlers, the second most frequent cause of death was congenital anomalies. Cancer was the second leading cause of death among school-age children. The third leading cause of death for school-age children was suicide. Chronic diseases (e.g., heart disease, chronic lower respiratory disease, and cerebrovascular diseases) also were among the leading causes of death for children. Note that the death rate among school-age children was lower than that among children aged 1 to 4 years. Overall statistics regarding mortality among children in 2011 are shown in Table 5.3.

| Table 5.3: Mortality among children in 2011 (United States) | ||||||||

| Age | 1–4 years | 5–14 years | ||||||

| Number of deaths | 4,450 | 5,651 | ||||||

| Deaths per 100,000 population | 26.1 | 13.9 | ||||||

| Leading causes of death |

|

| ||||||

| Source: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2012). FastStats. Child health. Mortality. Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/fastats/children.htm | ||||||||

Figure 5.4: Leading causes of death in 2010 for four age groups: 1–4, 5–9, 10–14, and 15–24

Source: Data adapted from CDC. Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/injury/wisqars/leading_causes_death.html

Many public health issues can lead to deaths in younger populations. How can unintentional injuries, homicide, and suicide be prevented in these groups?

National Geographic/SuperStock

The greatest causes of child death throughout the world, such as malnutrition, tend to be preventable.

Morbidity Patterns Among Children

This section covers illness due to a range of conditions: infectious diseases, asthma, and developmental disabilities. Although infectious diseases can occur at any age, some often appear during childhood, when children have not yet developed immunity against them. Also, childhood is a stage of life when developmental disabilities that can last a lifetime begin to appear.

Infectious Diseases and Conditions

Children are susceptible to numerous infectious diseases, which include the common cold and influenza, foodborne illness, diarrheal illnesses, pneumonia, and streptococcal and staphylococcal infections. Chapter 4 presented information on this topic.

One group of infectious diseases, for which vaccines are available, is called vaccine preventable diseases. These are diseases such as hepatitis, diphtheria, polio, influenza, chickenpox, and meningitis. Recommended immunization schedules are somewhat different for children aged 0 to 6 years and 7 through 18 years (CDC, 2012i). Among younger children, the recommended immunization schedule covers 11 diseases (e.g., hepatitis B, rotavirus, and Haemophilus influenzae type b). Recommendations for older children include vaccinations for 10 diseases, including the human papilloma virus (HPV), for which a relatively new vaccination is now available. High levels of children's compliance with recommended immunization schedules are vital to controlling unnecessary outbreaks of infectious diseases and protecting the health of the community.

Asthma

Asthma is one of the most common chronic diseases among children in this country and also a major cause of school absenteeism (CDC, 2012b). The symptoms of asthma include breathing difficulties such as wheezing, chest tightness, and coughing; fatal attacks can occur. Triggers for asthma attacks are tobacco smoke and dust mites.

The prevalence of asthma is on the rise and increased between 2001 and 2009 (CDC, 2011a). During 2007, a total of 185 children's deaths from asthma were reported in the United States. In 2009, the prevalence of asthma among children reached 10%; the condition was more common among boys than girls. The highest rate of childhood asthma (17%) in 2009 was among non-Hispanic Black children, though the reasons for this high rate are not clearly understood yet.

Developmental Disabilities

Developmental disabilities are "a group of conditions due to an impairment in physical, learning, language, or behavior areas" (CDC, 2012c). Often, developmental disabilities become apparent when a child is not meeting age-appropriate developmental milestones—for example, walking or talking. Developmental disabilities usually are permanent and continue throughout a person's life. The causes of developmental disabilities include genetic factors, smoking and drinking during pregnancy, infections during pregnancy, and exposures to environmental toxins. An example of a developmental disability is Down syndrome, which is a chromosomal abnormality. Table 5.4 shows other examples of developmental disabilities. The following sections provide more detail on some of the noteworthy developmental disabilities.

| Table 5.4: Examples of developmental disabilities | |

| Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) | Intellectual disability |

| Autism Spectrum Disorders (ASDs) | Kernicterus (brain damage caused by untreated jaundice among newborns) |

| Cerebral palsy (CP) | Muscular dystrophy |

| Fetal alcohol spectrum disorders | Tourette syndrome |

| Fragile X syndrome | Vision impairment |

| Hearing loss | Learning disability |

| Source: CDC. (2012). Developmental disabilities. Specific conditions. Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/developmentaldisabilities/specificconditions.html | |

Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) is a condition that is marked by difficulty in paying attention and lack of impulse control (CDC, 2010a). ADHD typically begins in childhood and continues into adulthood. Many children normally have difficulty concentrating on a specific task and misbehave from time to time. Eventually, normal children outgrow these behaviors; among children with ADHD, these symptoms persist into older childhood, causing adjustment difficulties. The etiology of ADHD remains unknown, although there may be a genetic linkage. Some of the symptoms of ADHD are:

Difficulty paying attention in class

Frequent daydreaming

Easily distracted

Keeping in constant motion

Not thinking before acting.

Autism Spectrum Disorders (ASDs) are a group of disorders that involve difficulties in social interaction and impairment of language, thinking, and feelings (National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences [NIEHS], 2012). A 2008 surveillance program of more than 300,000 children aged 8 years reported that the estimated prevalence of ASD was 11.34 per 1,000 children. The prevalence of ASD was higher among boys (18.4 per 1000 boys) than among girls (4.0 per 1000 girls). The condition was more prevalent among non-Hispanic White children than among either non-Hispanic Black children or Hispanic children (CDC, 2012h). The causes of ASD have not been fully elucidated, although some research points to the role of genetic background and interactions between genes and the environment. For example, a study of twins suggested that autism is an inherited disorder influenced by environmental factors (Hallmayer et al., 2011). Twins share genetic characteristics as well as common prenatal and early postnatal environments, suggesting that both genetic and environmental influences are implicated in autism. It is hypothesized that environmental factors play a role in triggering or suppressing genetic susceptibility to autism during crucial developmental stages of life.

Intellectual Disability, also called mental retardation, is characterized by delay in reaching developmental milestones such as sitting up and walking, difficulty in speaking, and impairment of memory (CDC, n.d.). Intellectual disability can range in severity from mild to severe. The potential causes of intellectual disability are injuries, infections, and diseases that affect the brain, Down syndrome, genetic conditions, and birth defects. According to data from the National Health Interview Survey for 1997 through 2008, the prevalence of intellectual disabilities is 0.71% (0.59% among children ages 3 through 10 and 0.84% among children ages 11 through 17). The condition is more prevalent among non-Hispanic Blacks, boys, children of mothers who have lower educational levels, and children from families who are below 200% of poverty level (Boyle et al., 2011).

5.5 Adolescents

Adolescence, a time of life when children initiate the transition into adulthood, has noteworthy patterns of morbidity and mortality, many of which are a reflection of lifestyle and behavior. Patterns observed in late adolescence predict many of those that occur among young adults. Consequently, mortality and morbidity data for older adolescents and young adults often are combined for statistical purposes. Chapter 6 will extend the coverage of the material presented on adolescent health in this section.

Healthy People 2020 prioritizes adolescent health, which is crucial for one's entire life. The goal of Healthy People with respect to this topic is to "[i]mprove the healthy development, health, safety, and well-being of young adolescents and young adults" (HealthyPeople.gov, 2012a, para. 1). Health-related behaviors that are established during adolescence tend to carry over into adulthood and affect individuals later in life. Health Care in Action: Healthy People 2020 Summary of Objectives provides the summary of Healthy People 2020's objectives in the domain of adolescent health.

Health Care in Action: Healthy People 2020 Summary of Objectives

Adolescent Health

Number and Objective Short Title

AH–1 Adolescent wellness checkup

AH–2 Afterschool activities

AH–3 Adolescent-adult connection

AH–4 Transition to self-sufficiency from foster care

AH–5 Educational achievement

AH–6 School breakfast program

AH–7 Illegal drugs on school property

AH–8 Student safety at school as perceived by parents

AH–9 Student harassment related to sexual orientation and gender identity

AH–10 Serious violent incidents in public schools

AH–11 Youth perpetration of, and victimization by, crimes

Source: HealthyPeople.gov. (n.d.). Healthy People 2020 summary of objectives. Adolescent health, p. AH-1. Retrieved from http://www.HealthyPeople.gov/2020/topicsobjectives2020/pdfs/HP2020objectives.pdf

Blue Jean Images/SuperStock

As teenagers begin to make their way into adulthood, their patterns of behavior change too. These new lifestyle behaviors affect adolescent mortality rates.

Causes of Death Among Adolescents

During both late and early adolescence, the leading cause of death is unintentional injuries. The other leading causes of mortality vary somewhat between younger adolescents and older adolescents, whose mortality patterns are similar to those of young adults. (Refer to Figure 5.4.)

In 2010, the three leading causes of death among 10- to 14-year-old children were unintentional injuries, malignant neoplasms, and suicide (CDC, 2012t). Other major causes were homicide, congenital anomalies, chronic lower respiratory disease, benign neoplasms, heart disease, cerebrovascular diseases, and septicemia. Among 15- to 24-year-olds, the three leading causes of death in 2010 also were unintentional injuries and suicide (rank 1 and 3), with homicide ranked in second place. Many of the remaining causes of death for this age group were similar to the patterns observed among 10- to 14-year-olds with the exception of the addition of malignant neoplasms, influenza and pneumonia, and complications of pregnancy. Septicemia, benign neoplasms, and chronic lower respiratory disease did not rank among the 10 leading causes for the older age group.

Table 5.5 gives 2009 data on the causes of death for older teenagers (15 to 19 years of age) and excludes young adults. Once again the leading cause of death was unintentional injuries. Chronic lower respiratory diseases were among the leading causes of death for older teenagers, as was also true of 10- to 14-year-old children.

| Table 5.5: Leading causes of death all races, both sexes, 15–19 years, 2009 | ||||||

| Rank | Cause of death | Number | Percent of total deaths | Death rate | ||

| . . . | All causes | 11,520 | 100.0 | 53.5 | ||

| Accidents (unintentional injuries) | 4,807 | 41.7 | 22.3 | |||

| Assault (homicide) | 1,919 | 16.7 | 8.9 | |||

| Intentional self-harm (suicide) | 1,669 | 14.5 | 7.7 | |||

| Malignant neoplasms | 644 | 5.6 | 3.0 | |||

| Diseases of heart | 335 | 2.9 | 1.6 | |||

| Congenital malformations, deformations, and chromosomal abnormalities | 230 | 2.0 | 1.1 | |||

| Influenza and pneumonia | 163 | 1.4 | 0.8 | |||

| Chronic lower respiratory diseases | 86 | 0.7 | 0.4 | |||

| Septicemia | 61 | 0.5 | 0.3 | |||

| 10 | Cerebrovascular diseases | 60 | 0.5 | 0.3 | ||

| . . . | All other causes (residual) | 1,546 | 13.4 | 7.2 | ||

| Source: Data from Heron, M. (2012). Deaths: Leading causes for 2009. National Vital Statistics Reports, 61(7), 17. | ||||||

In summary, injuries of all kinds rank among the leading causes of death for teenagers. In addition to injuries, many of the causes of death have behavioral determinants. The remainder of this section presents information on injuries and behaviorally related risk factors for adverse health outcomes.

Injuries: Unintentional and Intentional

Image Source/SuperStock

Car accidents are the leading cause of unintentional injury and death among adolescents.

The CDC defines an injury as "unintentional or intentional damage to the body resulting from acute exposure to thermal, mechanical, electrical, or chemical energy or from the absence of such essentials as heat or oxygen" (CDC, 2010c). As noted, unintentional injuries and intentional injuries (homicide, suicide, and poisoning) are the leading causes of adolescent deaths. Injury-related causes account for about 67% of all deaths among children and adolescents between the ages of 5 and 9 years (CDC, 2010c). Representative statistics from 2005 for injury deaths are as follows:

Motor vehicle injuries—48% of injury deaths

Homicide—16% of injury deaths, varies by race/ethnicity with highest rates among Blacks in comparison with non-Hispanic Whites.

Suicide—16% of injury deaths.

Violence is one of the major causes of injuries. Examples of violence-associated injuries include:

Youth violence at school and in the community

Dating violence—physical and sexual abuse of a dating partner

Violence against lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) youth—school-related violence takes the form of verbal harassment, physical harassment, and physical assaults (CDC, 2011f).

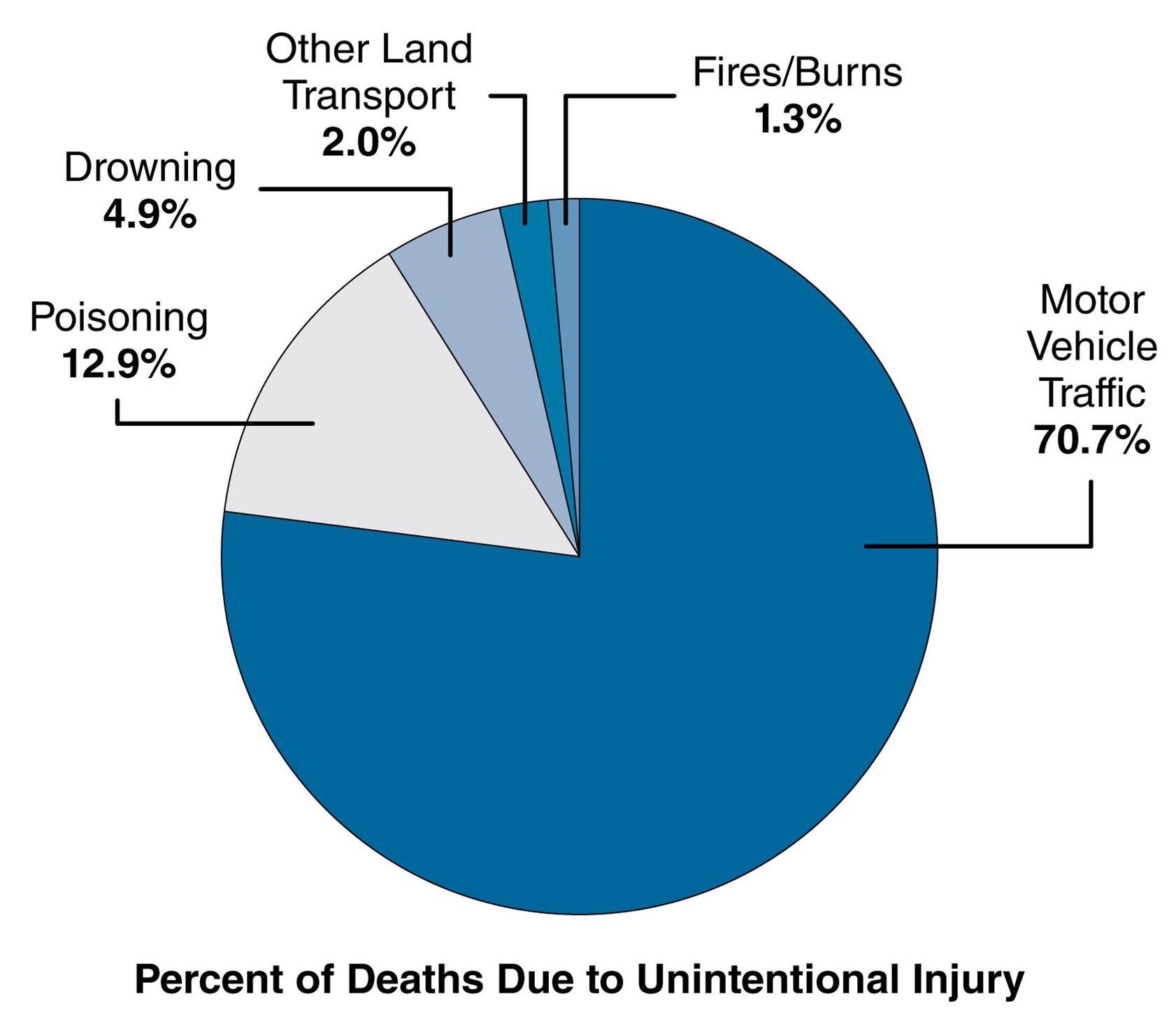

Unintentional Injuries

A common term for unintentional injuries is accidents (referring to a chance occurrence), but the use of this term is discouraged because most unintentional injuries are preventable. Figure 5.5 shows the distribution of deaths from unintentional injuries. Note the major contribution of motor vehicle injuries.

Figure 5.5: Deaths due to unintentional injury among adolescents aged 15 to 19 years, 2007

Source: Adapted from Child Health USA. (2011). p. 53. Retrieved from http://mchb.hrsa.gov/chusa11/

Motor vehicle deaths make up over 70% of youth deaths.

Prevention

Each type of injury-related death has a set of identifiable risk factors. For example, failure to wear a bicycle helmet increases the risk of serious injuries from bicycle mishaps. Other examples of risk factors for unintentional injuries and intentional injuries (from suicide and violence) are shown in Table 5.6.

| Table 5.6: Risk factors for unintentional injuries (bicycle- and motor vehicle-related) and intentional injuries (suicide and violence-related) | |||||||

| Unintentional Injuries | Suicide | Violence | |||||

| Rarely or never wore a bicycle helmet | Felt sad or hopeless | Carried a gun or other weapon | |||||

| Rarely or never wore a seat belt | Seriously considered attempting suicide | Carried a weapon on school property | |||||

| Rode with a driver who had been drinking alcohol | Made a suicide plan | Threatened or injured with a weapon on school property | |||||

| Drove when drinking alcohol | Attempted suicide | In a physical fight | |||||

| Texted or emailed while driving | Suicide attempt treated by a nurse or doctor | Bullied on school property or electronically bullied | |||||

| Source: Data from Eaton, D. K., Kann, L., Kinchen, S., Shanklin, S., Flint, K. H., Hawkins, J, . . . Wechsler, H. (2012). Youth risk behavior surveillance—United States, 2011. MMWR 61(4, pp. 4-12). | |||||||

Prevention of injuries can be accomplished through the implementation of appropriate, evidence-based, and readily available interventions. For example, many unintentional injuries connected with motor vehicle use are associated with drinking and driving; school-based interventions can discourage underage alcohol consumption. One of the risk factors for self-inflicted injuries (suicide) is severe depression, which has a high success rate for treatment when intervention is begun early.

Youth violence in America is a major public health issue (Hahn et al., 2007). Intentional injuries caused by homicide and school violence are increasingly notorious problems in America's schools and have been linked to carrying weapons and bringing a gun to school. School violence includes physical bullying and intimidation as well as the more recent phenomenon of cyberbullying. Preventive measures for reducing violence include increasing employment for youth, as well as mobilizing community residents and school officials to discourage violent behavior. In addition, sex education programs for students who are attending schools can help to prevent intimate partner violence.

Universal school-based violence prevention programs are directed toward all students regardless of their level of risk for violence (Hahn et al., 2007). An example of such a program is the Violence Prevention Curriculum for Adolescents, which focuses on the causes of violence and development of skills for resisting violent behavior (Hahn et al., 2007). A second example is the Second Step program—directed toward violence prevention skills development and role playing combined with feedback and reinforcement (Hahn et al., 2007). The Safe Dates Program is a 10-session curriculum for adolescents who are involved in abusive relationships (Hahn et al., 2007).

Risk Behaviors Among Adolescents

Obesity in Childhood

Dr. Barbara Korsch and a team of researchers explain the progression of overweight babies to overweight adults, and the challenges in preventing obesity.

Critical Thinking Question:

How can community and public health professionals make positive changes in childhood obesity rates? What might be the most approachable factor of obesity to target for change?

The Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance System (YRBSS) monitors health risk behaviors that are associated with the primary causes of death and disability among a representative sample of U.S. high school students in public and private schools (Eaton et al., 2012). Examples of risk behaviors are failure to wear a seat belt when riding in a car, drinking, smoking, and not using condoms during sexual intercourse. In addition, the YRBSS collects information of the prevalence of obesity, which is related to chronic diseases such as diabetes. From 1999 to 2011, the prevalence of obesity among school-aged youth increased from 10.6% to 13.0% in 2011. Data from the YRBSS and presented in Table 5.7 show time trends in 15 risk behaviors and obesity between the years 1991 and 2011. In 2011, approximately 40% of high school students had at least one drink of alcohol on at least one day during the 30 days before the survey. Slightly fewer than one-fifth of students reported smoking cigarettes on at least one day. Other prevalent risky behaviors included:

riding with a driver who had been drinking

using marijuana

not using any method to prevent pregnancy during sexual intercourse (among students who were sexually active).

Refer to Table 5.7 for more information on selected risk behaviors and obesity.

| Table 5.7: Trends in the prevalence of selected risk behaviors and obesity for all students (9th through 12th grades), National YRBS: 1991–2011 | ||||||||||

| 1991 | 1993 | 1995 | 1997 | 1999 | 2001 | 2003 | 2005 | 2007 | 2009 | 2011 |

| Rarely or never wore a seat belt (when riding in a car driven by someone else) | ||||||||||

| 25.9 | 19.1 | 21.7 | 19.3 | 16.4 | 14.1 | 18.2 | 10.2 | 11.1 | 9.7 | 7.7 |

| Rode with a driver who had been drinking alcohol one or more times (in a car or other vehicle during the 30 days before the survey) | ||||||||||

| 39.9 | 35.3 | 38.8 | 36.6 | 33.1 | 30.7 | 30.2 | 28.5 | 29.1 | 28.3 | 24.1 |

| Carried a weapon on at least 1 day (for example, a gun, knife, or club during the 30 days before the survey) | ||||||||||

| 26.1 | 22.1 | 20.0 | 18.3 | 17.3 | 17.4 | 17.1 | 18.5 | 18.0 | 17.5 | 16.6 |

| Did not go to school because they felt unsafe at school or on their way to work from school on at least 1 day (during the 30 days before the survey) | ||||||||||

| NA | 4.4 | 4.5 | 4.0 | 5.2 | 6.6 | 5.4 | 6.0 | 5.5 | 5.0 | 5.9 |

| Attempted suicide one or more times (during the 12 months before the survey) | ||||||||||

| 7.3 | 8.6 | 8.7 | 7.7 | 8.3 | 8.8 | 8.5 | 8.4 | 6.9 | 6.3 | 7.8 |

| Smoked cigarettes on at least 1 day (during the 30 days before the survey) | ||||||||||

| 27.5 | 30.5 | 34.8 | 36.4 | 34.8 | 28.5 | 21.9 | 23.0 | 20.0 | 19.5 | 18.1 |

| Had at least one drink of alcohol on at least 1 day (during the 30 days before the survey) | ||||||||||

| 50.8 | 48.0 | 51.6 | 50.8 | 50.0 | 47.1 | 44.9 | 43.3 | 44.7 | 41.8 | 38.7 |

| Used marijuana one or more times (during the 30 days before the survey) | ||||||||||

| 14.7 | 17.7 | 25.3 | 26.2 | 26.7 | 23.9 | 22.4 | 20.2 | 19.7 | 20.8 | 23.1 |

| Ever used methamphetamines one or more times (also called "speed," "crystal," or "ice," during their life) | ||||||||||

| NA | NA | NA | NA | 9.1 | 9.8 | 7.6 | 6.2 | 4.4 | 4.1 | 3.8 |

| Ever had sexual intercourse | ||||||||||

| 54.1 | 53.0 | 53.1 | 48.4 | 49.9 | 45.6 | 46.7 | 46.8 | 47.8 | 46.0 | 47.4 |

| Had sexual intercourse with four or more persons (during their life) | ||||||||||

| 18.7 | 18.7 | 17.8 | 16.0 | 16.2 | 14.2 | 14.4 | 14.3 | 14.9 | 13.8 | 15.3 |

| Used a condom during last sexual intercourse (among students who were currently sexually active) | ||||||||||

| 46.2 | 52.8 | 54.4 | 56.8 | 58.0 | 57.9 | 63.0 | 62.8 | 61.5 | 61.1 | 60.2 |

| Did not use any method to prevent pregnancy during last intercourse (among students who were currently sexually active) | ||||||||||

| 16.5 | 15.3 | 15.8 | 15.3 | 14.9 | 13.3 | 11.3 | 12.7 | 12.2 | 11.9 | 12.9 |

| Attended physical education daily | ||||||||||

| 41.6 | 34.3 | 25.4 | 27.4 | 29.1 | 32.2 | 28.4 | 33.0 | 30.3 | 33.3 | 31.5 |

| Obese | ||||||||||

| NA | NA | NA | NA | 10.6 | 10.5 | 12.0 | 13.0 | 12.8 | 11.8 | 13.0 |

| (Numbers shown are percentages and 95% confidence intervals.) | ||||||||||

Teenage Pregnancy

Teenage pregnancy can have unfortunate impacts upon the physical and social health of the teenaged mother, the father, and the community, which must incur substantial economic costs. One of these adverse outcomes is an increase in school dropout rates among teenage girls who become pregnant. Also, teenage pregnancy causes billions of dollars in direct costs for health care and other expenses related to the care of children born to teenagers. Often, children of teenage mothers have lowered school achievement and increased dropout rates; the sons of teenage mothers have higher frequencies of criminality and incarceration (CDC, 2012a). For example, one review reported that the sons of teenage mothers were more than twice as likely to be confined in prison than sons of women who waited to have children until they were in their early 20s (Hoffman, 2006).

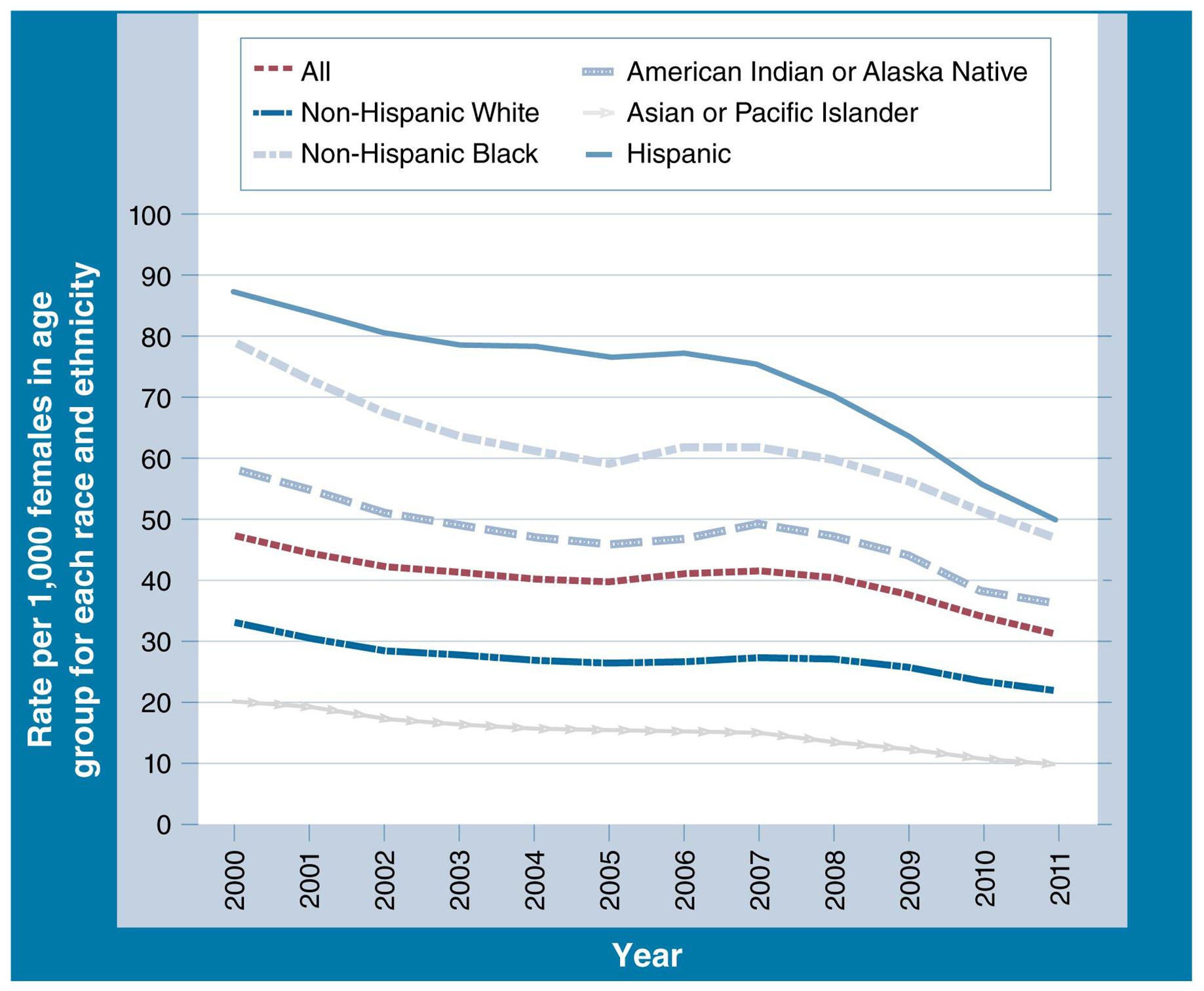

In the United States, the number of births among females between the ages of 15 and 19 years in 2011 was 329,797, which was a birth rate of 31.3 per 1,000 (Hamilton, Martin, & Ventura, 2012). In this age range, the number of births declined by 8% from the previous year (CDC, 2012a). Figure 5.6 shows trends in the birth rates among teenaged women aged 15–19 years between 2000 and 2011. The figure demonstrates that birth rates have declined over time among almost all racial and ethnic groups. An exception is the birth rate among 18- to 19-year-old Asian/Pacific Islanders (CDC, 2012a), which group is not shown in the figure.

Figure 5.6: Birth rates (live births) per 1,000 females aged 15 to 19 years by race and Hispanic ethnicity, 2000–2011

Source: Adapted from CDC.

What does this downward trend in teenage pregnancy and birth suggest about public programs aimed at these populations? What factors might contribute to the disparity between ethnicities?

Racial and Social Disparities in Teenage Birth Rates

Disparities occur among the teenage birth rates of racial and ethnic groups in the United States. The greatest disparities exist among the teenage birth rates of both Hispanic females and non-Hispanic Black females in comparison with other racial and ethnic groups. In 2011, the respective teenage birth rates for Hispanic females and non-Hispanic Black females were 49.4 per 1,000 and 47.4 per 1,000 (Hamilton et al., 2012). Non-Hispanic Black and Hispanic females accounted for about 57% of teen births in 2011 (CDC, 2012a). The rates for non-Hispanic Whites and Asian or Pacific Islanders were 21.8 per 1,000 and 10.2 per 1,000, respectively.

The causes of racial disparities in teenage birth rates are multifactorial. One of the variables associated with lower teenage birth rates is contraceptive use. A larger percentage of sexually active White adolescent females use effective methods of contraception than non-Hispanic Black and Hispanic females (USDHHS, 2013). Another related factor is frequency of sexual activity among different groups. A New York City study reported higher rates of sexual activity among non-Hispanic Black and Hispanic high school girls than among White girls (Waddell et al., 2010). Also, teenage motherhood tends to be transferred across generations, with the daughters of women who were teenagers themselves becoming teenage mothers (Gaudie et al., 2010). Lastly, the risk of teenage pregnancy is higher among families headed by a single parent as well as among dysfunctional families (Gaudie et al., 2010).

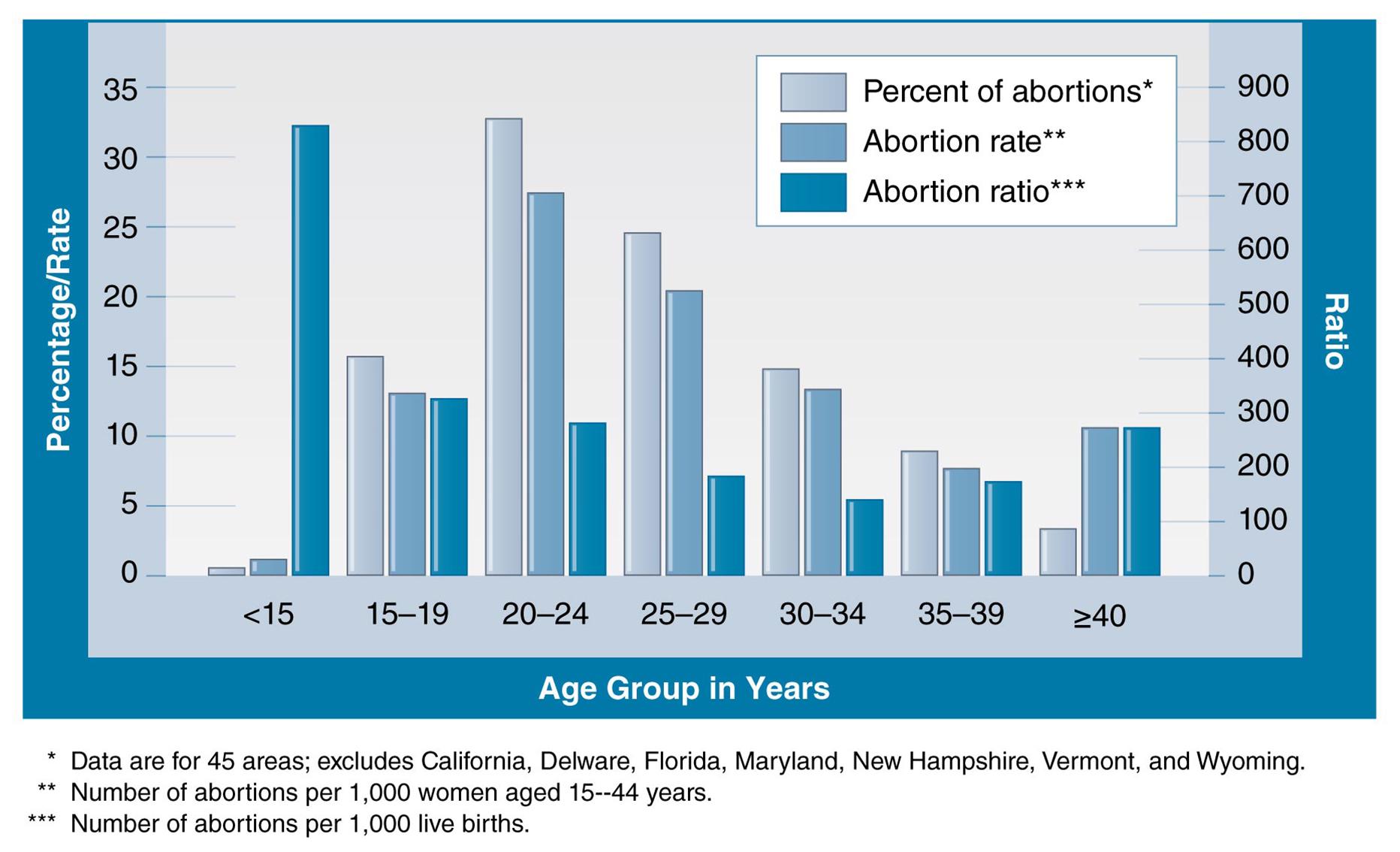

Unintended Pregnancies/Abortion

One of the objectives of Healthy People 2020 is to increase the proportion of pregnancies that are intended. About one half of all pregnancies in the United States are unintended, meaning that they are unplanned or unwanted. Among teenagers between the ages of 15 and 17 years, approximately 80% of pregnancies are unintended (CDC, 2012p). Unintended pregnancy is a major contributor to abortion.