HCA415 Community & Public Health-WK2-A1

Chapter 7 Community Health and the Environment

7.1 Introduction

The field of environmental health has a broad scope, as noted in the following definition from the World Health Organization (WHO). According to the WHO, environmental health

addresses all the physical, chemical, and biological factors external to a person, and all the related factors impacting behaviours. It encompasses the assessment and control of those environmental factors that can potentially affect health. It is targeted towards preventing disease and creating health-supportive environments. (WHO, 2012, para. 1)

The physical environment is one of the most crucial dimensions of the health of communities globally and in the United States. As we discussed in Chapter 2, ecology is a field science that specializes in the relationships between organisms and their environment. The late Barry Commoner, who was a noted ecologist, stressed the interrelationships among environmental influences and their connection with living organisms (Commoner, 1974). His four laws of ecology (see Spotlight: The Four Laws of Ecology) will help frame this chapter.

Spotlight: The Four Laws of Ecology

Everything Is Connected to Everything Else.

"[T]he system is stabilized by its dynamic self-compensating properties; these same properties, if overstressed, can lead to a dramatic collapse" (p. 35).Everything Must Go Somewhere.

"[I]n nature there is no such thing as 'waste.' In every natural system, what is excreted by one organism as waste is taken up by another as food" (p. 36).Nature Knows Best.

"One of the most pervasive features of modern technology is the notion that it is intended to 'improve on nature'—to provide food, clothing, shelter, and means of communication and expression which are superior to those available to man in nature. Stated baldly, the third law of ecology holds that any major man-made change in a natural system is likely to be detrimental to that system" (p. 37).There Is No Such Thing as a Free Lunch.

"Because the global ecosystem is a connected whole, in which nothing can be gained or lost and which is not subject to over-all improvement, anything extracted from it by human effort must be replaced. Payment of this price cannot be avoided; it can only be delayed. The present environmental crisis is a warning that we have delayed nearly too long" (p. 42).

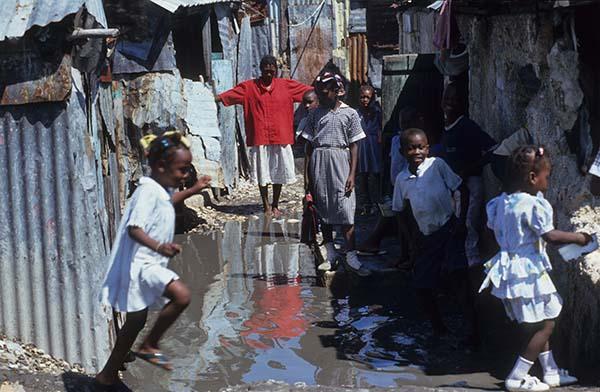

Universal Images Group/SuperStock

Among the slums of Haiti, Cite Soleil Shanty Town stands as an example of the poor living conditions common to other such disadvantaged areas. Residents here face challenges implementing effective sanitation and obtaining clean water. As a result, the environment is ripe for the spread of infectious disease.

Environmental hazards associated with work, the home setting, recreation, or commuting to work affect the health of almost all human beings and demonstrate ecological principles in operation. This chapter explores environmental determinants of human morbidity and mortality. The topics covered include types of environmentally associated health hazards; heightened risk of adverse environmental effects among vulnerable populations; methods for protecting the community from environmental hazards; and techniques for structuring the built environment for creation of optimal community health.

The WHO notes that during the beginning of the present century, changeable environmental factors accounted for about one-quarter of the global burden of disease (Prüss-Üstün & Corvalán, 2006). Among the world's children, the burden of environmentally associated disease was even higher—approximately one-third. WHO reported that almost 10% of the world's deaths and disease burden were related to five environmental factors (WHO, 2009):

indoor air pollution from smoke generated by solid fuels

unsafe water in combination with poor sanitation and hygiene

outdoor air pollution in cities

global climate change

lead exposure.

Although health effects caused by the environment are particularly acute in developing countries, many of the same environmental factors also contribute to adverse health outcomes in the United States. High air pollution levels in some of America's cities have been linked to asthma attacks, lung diseases, heart disease, cancer, and exacerbation of other chronic diseases. In addition, urban air pollution has been shown to have a direct association with mortality. Toxic wastes, pesticides used in agriculture and in people's homes, and urban runoff have permanently contaminated water supplies in some regions of the nation. Finally, children and adults who live near industrial facilities may be exposed to unsafe levels of toxic pollutants. These are only a few examples of environmental hazards that are affecting communities in some parts of the country. The next few sections discuss the various types of environmental hazards.

7.2 Environmental Hazards: Toxic Chemicals

Centers for Disease Control

Toxic chemicals leak from a 50-gallon drum, endangering those who might come into contact with the liquid. Many chemicals are potential health and environmental hazards and thus must be properly stored and disposed of.

The negative consequences of exposure to toxic chemicals such as pesticides (e.g., DDT [dichlorodiphenyl- trichloroethylene]) and other chemicals (e.g., dioxins and PCBs [polychlorinated biphenyls]) are a major concern of environmental professionals. Because toxic chemicals are essential to many vital industrial processes and are used commonly in the home, humans have many occasions for exposure to them. Toxic chemicals can be used with appropriate safeguards in order to prevent adverse effects for human health and the environment.

A few examples (by no means an exhaustive list) of chemicals that represent potential health and environmental hazards are solvents, PCBs, dioxins, and chemicals used for the manufacture of plastics. Across the United States, chemicals that are leaking from inadequate storage sites endanger the environment.

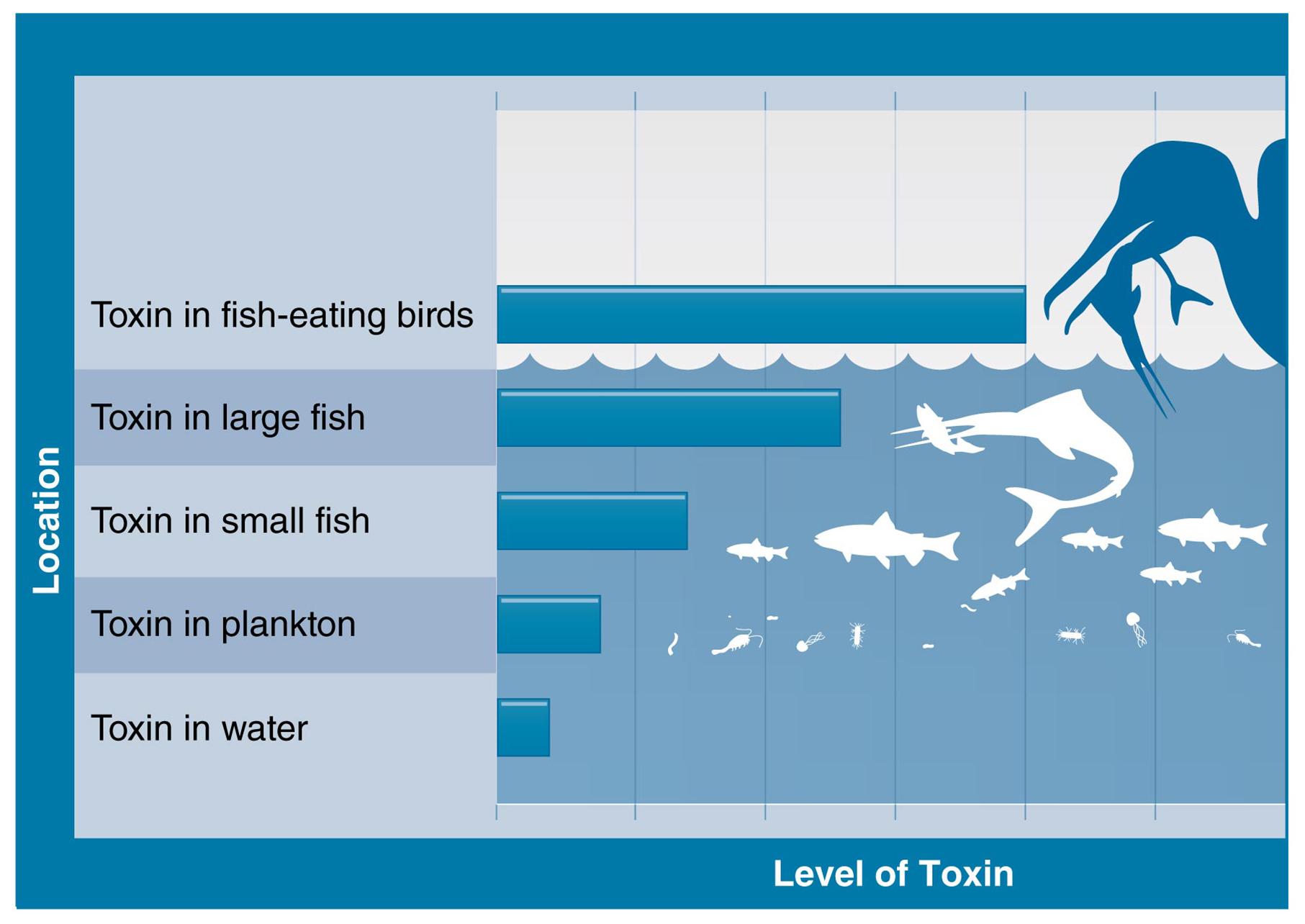

Among the hazards associated with some toxic chemicals are biological accumulation, biological amplification, carcinogenicity, persistence in the environment, and ability to mimic sex hormones. These terms are explained in Table 7.1. Figure 7.1 illustrates the process of biological amplification.

| Table 7.1: Terms related to chemical hazards in the environment | |

| Term | Definition |

| Biological accumulation (bioaccumulation) | The uptake and storage of chemicals (e.g., DDT, PCBs) from the environment by animals and plants. Uptake can occur through feeding or direct absorption from water or sediments. |

| Biological amplification (also called bioamplification, biomagnification, or bioconcentration) | The concentration of a substance as it "moves up" the food chain from one consumer to another. The concentration of chemical contaminants (e.g., DDT, PCBs, methyl mercury) progressively increases from the bottom of the food chain (e.g., phytoplankton, zooplankton) to the top of the food chain (e.g., fish-eating birds such as cormorants). |

| Carcinogenic chemical | Chemical that causes cancer |

| Dioxin—TCDD (2, 3, 7, 8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin) | Toxic chemical produced as a byproduct of industrial processes |

| DDT (dichloro-diphenyl-trichloroethylene) | Synthetic pesticide developed in the 1940s |

| Endocrine disruptors | Chemicals that mimic sex hormones and thereby interfere with reproductive processes; they have the potential to impair development, the immune system, reproduction, and neurological functioning in both humans and animals. When present in lakes and rivers, endocrine disruptors could affect aquatic animals. In addition to being persistent organic pollutants (POPs), DDT, dioxins, and PCBs are also regarded as endocrine disruptors. |

| Persistent organic pollutants (POPs) | Chemicals that remain in the environment for long periods; examples are DDT, dioxins, and PCBs. |

| Polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) | Toxic synthetic chemicals with many applications (e.g., in electrical devices and coatings) |

| Solvent | A liquid that has the ability to dissolve other substances |

| Toxic chemical | Poisonous chemical; examples are synthetic organic chemicals such as PCBs and DDT. |

| Source: The definitions of biological accumulation and biological amplification are adapted and reprinted from United States Environmental Protection Agency. (2006). Volunteer estuary monitoring manual, a methods manual (2nd ed.; p. 12-3). EPA- 842-B-06-003. | |

Figure 7.1: Biological amplification

Source: Adapted from Environmental Protection Agency. (2006, March). Volunteer estuary monitoring manual, a methods manual (2nd ed.; p. 12-3). EPA-842-B-06-003.

One hazard associated with toxic chemicals is biological amplification, in which the chemical concentration increases at successive levels of the food chain. A small amount of a chemical in the water has a much greater effect on a fish-eating bird than a large fish, for example, because of the amount of the chemical the bird ingests and stores when it eats the large fish.

Solvents

Because of their ability to dissolve other substances, solvents are used as constituents of paints, paint thinners, and grease removers. They are employed widely for industrial and manufacturing applications. Also, the dry cleaning industry is a familiar venue for the use of solvents. Examples of solvents are shown in Table 7.2.

| Table 7.2: Examples of solvents | |

| Name | Uses |

| Benzene | In drugs and chemicals; in gasoline |

| Carbon tetrachloride | As a cleaning fluid; propellant for aerosol cans (uses for most purposes are now banned) |

| Methylene chloride (dichloromethane) | In paint removers |

| Tetrachloroethylene | As a dry cleaning chemical |

| Trichloroethylene | Cleaning agents, paint removers |

A number of solvents (for example, those shown in Table 7.2), are known or suspected causes of cancer in experimental animals, but their role as human carcinogens is only suggestive (NCI & NIEHS, 2003). However, benzene has been demonstrated conclusively to be a cause of cancer in humans. Benzene is a colorless, flammable liquid used in a wide range of manufacturing applications and also occurs in automobile exhaust. Refer to Spotlight: Benzene for more information about benzene.

Spotlight: Benzene

iStockphoto/Thinkstock

Because gasoline contains benzene, which permeates the air around service stations, gas station employees face increased exposure to this cancer-causing agent.

According to the NCI and NIEHS,

Benzene is known to cause leukemia in humans. It has widespread use as a solvent in the chemical and drug industries and as a gasoline component. After 1997, its use as an ingredient in pesticides was banned. Workers employed in the petrochemical industry, pharmaceutical industry, leather industry, rubber industry, gas stations, and in the transportation industry are exposed to benzene. Inhaling contaminated air is the primary method of exposure. Because benzene is present in gasoline, air contamination occurs around gas stations and in congested areas with automobile exhaust. It is also present in cigarette smoke. It is estimated that half of the exposure to benzene in the United States is from cigarette smoking. About half of the U.S. population is exposed to benzene from industrial sources, and virtually everyone in the country is exposed to benzene in gasoline.

Source: National Cancer Institute and National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences. (2003). Cancer and the environment, pp. 12–13.

Polychlorinated Biphenyls (PCBs)

Polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) are a group of man-made chemicals that ceased production in the United States in 1977. Formerly, they were used for insulating, cooling, and lubricating transformers and other electrical devices. They were also used in numerous other products such as paints and plastics. PCBs are regarded as persistent organic pollutants (POPs) because they remain in the environment for very long periods of time. They have the ability to bioaccumulate and bioamplify in fish and other aquatic animals. People who consume sport fish from lakes and rivers can be exposed to PCBs. Researchers have demonstrated that PCBs can cause cancer in animals (USEPA, 2012b). The United States Environmental Protection Agency has concluded that PCBs are probable human carcinogens.

AFP/Getty Images

Members of an environmental group, shown here, work to raise awareness of the number of local toys containing phthalates in Manila. Six of seven toys tested were shown to contain the toxic chemicals.

Dioxins

The common chemical name for dioxin is TCDD (2, 3, 7, 8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin). Dioxins are hazardous to the environment because of their high level of toxicity, persistence in the environment, and ability to bioamplify. (Refer to Table 7.1 for more information on these terms.) Toxicity is "[t]he degree to which a substance (a toxin or poison) can harm humans or animals" (MedicineNet.com, 2012, para. 1). Industrial processes can produce dioxins as a byproduct. Naturally occurring dioxins are the result of volcanic eruptions and forest fires (WHO, 2010). Because exposure to dioxins is fairly common, most people have small amounts of dioxin in their bodies. One of the main sources of exposure of most persons to dioxin is via consumption of dioxin-contaminated foods, particularly those derived from animal fats: for example, from beef and pork, milk and dairy products, poultry, and fish (USEPA, 2013f). The form of dioxin called TCDD is a human carcinogen linked with several forms of cancer, including lung cancer and non-Hodgkin's lymphoma. Dioxin exposure also is associated with a range of other adverse health effects, including reproductive and developmental problems, heart disease, diabetes, and suppression of the immune system.

Plastics/Phthalates

Plastics are remarkable for their universality and multitude of applications in modern society. Two ingredients in plastics, bisphenol A (BPA), and phthalates, have raised concerns about their potential adverse health effects. BPA is a chemical used in the production of polycarbonate plastics and resins. A frequent use for plastics that contain BPA is for the manufacture of food and beverage containers. BPA can leach out from containers into foods kept in them. As a result, the main source of exposure to BPAs is some foods and beverages that people consume. For much of its history, BPA was considered to be safe. However, recent animal studies that showed reproductive and developmental defects associated with exposure to BPA have raised concerns about its safety (Halden, 2010).

Used as plasticizers to increase the flexibility of plastics, phthalates are added to children's toys, medical equipment, personal care products, and packaging for food stuffs. Phthalates in toys can be ingested when children chew on them. Phthalates are able to leach out of plastic containers and contaminate foods and beverages. Phthalates might contaminate intravenous fluids and blood products stored in plastic bags made with this plasticizer. Although the health risks of exposure to phthalates are a matter of debate, one of their potential health effects is hypothesized to be endocrine disruption (Halden, 2010).

Pesticides

A pesticide is defined as

any substance or mixture of substances intended for: preventing, destroying, repelling, or mitigating any pest. . . . Pests are living organisms that occur where they are not wanted or that cause damage to crops or humans or other animals. Examples include . . . insects, mites and other animals, unwanted plants (weeds), fungi, [and] microorganisms such as bacteria and viruses. (USEPA, 2013a)

Among the numerous products available for household and industrial uses are insect baits, rat poisons, pesticides (e.g., flea and tick sprays) applied to pets, and aerosol pesticides used inside and outside the home.

Pesticides have both risks and benefits for society. Their benefits include control of harmful or unwanted insects, organisms, and plants (e.g., through the use of defoliants to control weeds). Agricultural pesticides are essential for the control of harmful insects that attack crops and cause huge monetary losses. At the same time, pesticides have the potential to injure human beings and animals and to remain in the environment for long periods. Consequently, organic farming methods have gained popularity in recent years. Rachel Carson's groundbreaking work Silent Spring, published in 1962, helped to focus the public's attention on the harmful effects of pesticides and encouraged improved controls over pesticide use (Carson, 1962).

Many pesticides decompose shortly after they are used. However, this is not always the case. Among the concerns associated with some pesticides are their persistence and potential to bioaccumulate and biomagnify in the environment. The first of the modern synthetic pesticides, developed in the 1940s, was DDT (dichloro-diphenyl-trichloroethylene). At first, farmers found DDT to be extremely effective for controlling insects such as those that carried human and animal diseases (for example, malaria and typhus), damaged crops, and invaded homes and institutions. However, The United States ended its use in 1972 after it became linked with adverse environmental effects including harm to wildlife and long-term environmental persistence—especially its tendency to build up in fatty tissues of the body. Although no longer in use in this country, DDT can now be sprayed indoors in some countries or regions (for example, sub-Saharan Africa) that have malaria outbreaks or where endemic transmission of malaria is taking place. In 2006, the World Health Organization stated that indoor spraying of DDT could quickly reduce malaria infections and that DDT, if used properly, did not present a health risk (WHO, 2013b). See Spotlight: DDT—A Brief History and Status for more information.

Spotlight: DDT—A Brief History and Status

7.3 Environmental Hazards: Air Pollution

Air pollution—a stew of chemicals, gases, and particles—can be a potentially deadly threat to the health of the residents of cities and other geographic areas where the pollution drifts. In the developed world, progress has been made in controlling sources of air pollution. In the United States, the Clean Air Act was instrumental in addressing the causes of air pollution and helping to abate them. However, many of the rapidly growing and industrializing cities of the developing world urgently need to come to grips with the causes of highly polluted air that has become increasingly threatening. The People's Republic of China is an example of a rapidly industrializing country that has experienced continuing air pollution disasters.

Aerial shot of a city covered in smog.

CDC/Dr. Edwin P. Ewing, Jr.

Smog over the city of Chongqing, China. Air pollution has been a noticeable result of China's rapid industrialization.

Polluted air has been researched extensively as a risk factor for heart disease and related cardiovascular conditions, cancer, stroke, respiratory diseases, and mortality. Air pollution is associated with increased risk of heart attacks. Fine particles (i.e., invisible particles in air pollution), are able to bypass the body's filtering mechanisms and penetrate deeply. Some types of fine particles are able to circulate in the bloodstream and even gain access to the human brain.

Air Pollution Episodes in History

During the early 1930s through the late 1950s, cities in England, continental Europe, and the United States suffered from notorious and deadly episodes of extreme air pollution. At one time, many American cities were faced with disastrous levels of air contamination. These incidents increased the public's awareness of the harmful effects of air pollution and stimulated efforts to reduce air pollution levels. Among the notorious air pollution episodes were those in the Meuse Valley in Belgium; Donora, Pennsylvania; and London, England.

Meuse Valley, Belgium (December 1930): The Meuse Valley air pollution episode occurred in a highly industrialized region near Liege, Belgium. Levels of sulfuric acid mists, sulfur dioxide, and fluoride rose to toxic levels during the first week of December 1930. The deaths of more than 60 persons were believed to be related to the high pollution levels.

Donora, Pennsylvania (October 1948): Emissions from various sources that used fossil fuels (e.g., steel mills and home heating stoves), in this small town near Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, caused very severe air pollution. The event caused illnesses among half of the town's 14,000 residents, and 20 deaths were associated with it.

London (December 1952): A thick "pea-souper" fog enveloped London from December 5 through December 9, 1952. Following this lethal occurrence of air pollution, authorities reported an excess of 3,000 deaths above normal.

Black-and-white photo of people crossing the street in what looks like heavy fog.

CDC/ Barbara Jenkins, NIOSH

This photo was taken during an extreme air pollution event in 1950 in Salt Lake City, Utah.

Sources of Air Pollution

Air pollution is generated from outdoor and indoor sources and from anthropogenic activities and natural events. Examples of naturally occurring events that cause air pollution are volcanic eruptions and forest fires, both of which can inject huge amounts of pollutants into the upper atmosphere and can even be observed from outer space. Air pollution from anthropogenic activities comes from stationary and mobile sources. Stationary sources of air pollution include electric-generating plants that burn fossil fuels, factories, industrial complexes, wood- and coal-burning home fireplaces, fire rings at beaches, and backyard barbecues. Mobile sources of air pollution include on-road and off-road motor vehicles (e.g., automobiles, diesel trucks, and snowmobiles) and non-road vehicles (e.g., trains, aircraft, and ships).

Examples of sources of indoor pollution include smoke from biomass fuels used for cooking in developing countries, cigarette smoke, chemicals in household cleaning materials, dust mites and cockroaches, and chemical emissions from home construction materials and furniture. Biomass fuels are wood, animal dung, peat, and similar organic materials. We use the term building-related illness to describe diagnosable illnesses associated with indoor air pollutants.

Components of Outdoor Air Pollution

The components of outdoor air pollution include particles and toxic or dangerous gases such as carbon monoxide, sulfur dioxide, and ozone. These components can be either visible or invisible, as in the case of gases and very fine particles. Some air pollutants interact with one another, especially during high ambient temperatures, and produce visible clouds of pollutants known as smog. The term criteria air pollutants refers to six common air pollutants regulated by the EPA: ozone, nitrogen oxides, carbon monoxide, sulfur dioxide, particulate matter, and lead. The six criteria air pollutants, their sources, and health effects are shown in Table 7.3.

Table 7.3: Criteria air pollutants

Name of pollutant Source (examples) Potential health effects

Ozone (one of the molecular forms of oxygen) Combustion of fossil fuels, in combination with chemicals such as solvents Respiratory difficulties; eye irritation

Nitrogen oxides Combustion of fossil fuels (e.g., gasoline) Harm to respiratory system

Carbon monoxide (a poisonous gas) Produced by incomplete burning of fuels Aggravation of circulatory and respiratory diseases; causes death in high concentrations

Particulate matter Diesel exhaust; smoke from combustion Fine particles (smaller than 2.5 micrometers) can be inhaled deeply into the lungs, causing damage to the lungs and other parts of the body.

Sulfur dioxide Combustion of fossil fuels contaminated with sulfur; can form sulfuric acid Lung irritation; exacerbation of asthma

Lead Refining of metal ores that contain lead Neurological deficits

Acid Rain

The term acid rain refers to "a mixture of wet and dry deposition (deposited material) from the atmosphere containing higher than normal amounts of nitric and sulfuric acid" (USEPA, 2013r, para. 1). Most acid rain in the United States results from electric power plants that burn fossil fuels. The mild acidic solutions in acid rain can travel over long distances. When it settles on the ground and in bodies of water, acid rain can disrupt aquatic life and plants by increasing the acidity of the environment.

Air Quality Standards

The topics of air quality standards and control of air pollution are extensive and have evolved over many decades. Internationally and domestically, public health workers, government officials, and members of the community have been involved with the development of policies and other initiatives to improve air quality. For the United States, two exemplars of methods for protection of the public against the hazards of air pollution are the Clean Air Act and the air quality index. In the past few years, a policy known as cap and trade has been introduced as a means of controlling emissions of air pollution.

The Clean Air Act

Several laws, which have evolved over time, have made control of air pollution in the United States possible. The first was the Air Pollution Control Act of 1955. Subsequently, the Clean Air Act of 1963 and the Air Quality Act of 1967 were introduced. One of the most important legislative acts for control of air pollution was the Clean Air Act of 1970, which empowered the federal government to take steps to control air pollution through various regulatory policies and agencies. The United States Environmental Protection Agency was established around the same time to implement the new requirements.

The Clean Air Act of 1970 was revised in 1990. Congress reauthorized the Clean Air Act as part of the Clean Air Act Amendments (CAAA) of 1990. An important feature of the CAAA was the U.S. SO2 (sulfur dioxide) Allowance Trading Program (also known as the Acid Rain Program). This program is an example of cap and trade, a policy tool for reducing the levels of greenhouse gases such as sulfur dioxide. A limit, or cap, on total emissions is set for a group of sources, which are given "allowances" that they must surrender to cover their emissions. A financial incentive is offered for reducing emissions, and sources with low emissions are allowed to sell their allowances to others (USEPA, 2003).

Beginning in 1995, as part of its Acid Rain Program, the EPA limited (capped) emissions of SO2 from the highest polluting electric power plants in the Midwest, Appalachia, and Northeast states (USEPA, 2007). EPA distributed SO2 emissions allowances to each power plant; each allowance was valued at one ton of SO2. Each facility was required to release no more emissions than permitted by EPA's allowances and would be fined for exceeding emission limits. However, power plants that released more emissions than allowed could trade (purchase) allowances with more efficient plants (that is, plants that had achieved reductions in emissions and had more allowances than needed). In order to document compliance with the program, power plants were required to monitor emissions on a continuous basis.

According to environmental assessments, the SO2 Allowance Trading Program was effective in reducing total SO2 emissions by 33% between 1990 and 2001. The levels of SO2 concentrations in the air in the eastern United States have declined since 1988. Sulfate levels in precipitation also have declined since 1995 (USEPA, 2003).

Cap and trade programs such as the EPA's Acid Rain Program have been controversial because of their potential costs and adverse economic impacts. For example, the National Federation of Independent Business notes that the Congressional Budget Office (a nonpartisan group) projects costs of $821 billion for the federal government's cap and trade program and $846 in new energy taxes over a 10-year period (NFIB, 2009). The program would cause one million jobs to be lost each year and energy costs to rise substantially for individuals and small businesses.

Opposition to cap and trade programs has generated a myriad of lawsuits. One noteworthy case is a lawsuit to block California's cap and trade system, which went into effect in early 2012. A suit filed by the California Chamber of Commerce challenged the authority of the California Air Resources Board to establish allowances for greenhouse gas emissions, alleging that such allowances constituted an illegal tax (Dearen, 2012). So far, California's cap and trade law is destined for implementation despite numerous legal challenges.

Air Quality Index

The United States Environmental Protection Agency developed the air quality index (AQI) for reporting the quality of air in specific geographic areas of the United States (USEPA, 2009). It indicates whether air quality is good, moderate, or unhealthy. The AQI (which can range from 0 to 500) takes into account four major air pollutants regulated by the Clean Air Act; these are ozone, particles, carbon monoxide, and sulfur dioxide. Low index values suggest that air quality is good; as index values increase, air quality decreases (i.e., it becomes less and less healthy). For example, the maximum index range (301 to 500) denotes hazardous air quality. Refer to Figure 7.2 for more information about the AQI.

Figure 7.2: The air quality index

Figure that shows the levels of health concern given certain AQI values and their corresponding color. When the AQI is between 0 to 50, air quality conditions are good, as symbolized by the color green. When the AQI is between 51 to 100, the air quality is moderate, as symbolized by the color yellow. When the AQI is between 101 to 150, the air quality is unhealthy for sensitive groups, as symbolized by the color orange. When the AQI is between 151 to 200, the air quality is unhealthy, as symbolized by the color red. When the AQI is between 201 to 300, the air quality is very unhealthy, as symbolized by the color purple. When the AQI is between 301 to 500, the air quality is hazardous, as symbolized by the color maroon.

Source: United States Environmental Protection Agency. Office of Air Quality Planning and Standards. Outreach and Information Division. (2009, August). Air quality index. Research Triangle Park, NC. EPA-456/F-09-002, p. 2.

The AQI provides an easily accessible measure and analysis of air quality for the consumer.

Robert Huberman/SuperStock

DDT first gained popularity as a pesticide. Now, in addition to becoming less effective through insect-developed resistance, DDT is also a suspected carcinogen.

DDT was developed as the first of the modern synthetic insecticides in the 1940s. It was initially used with great effect to combat malaria, typhus, and the other insect-borne human diseases among both military and civilian populations, and for insect control in crop and livestock production, institutions, homes, and gardens. DDT's quick success as a pesticide in broad use in the United States and other countries led to the development of resistance by many insect pest species.

In 1972, the EPA issued a cancellation order for DDT based on adverse environmental effects of its use, such as those to wildlife, as well as DDT's potential human health risks. Since then, studies have continued, and a causal relationship between DDT and reproductive effects is suspected. Today, both U.S. and international authorities classify DDT as a probable human carcinogen. This classification is based on animal studies in which some animals developed liver tumors.

DDT is known to be very persistent in the environment, will accumulate in fatty tissues, and can travel long distances in the upper atmosphere. Since the use of DDT was discontinued in the United States, its concentration in the environment and animals has decreased, but because of its persistence, residues of concern from historical use still remain.

Source: Reprinted and adapted from United States Environmental Protection Agency. (2013e). DDT—A brief history and status. Retrieved from http://www.epa.gov/pesticides/factsheets/chemicals/ddt-brief-history-status.htm

The Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry states that

[m]any other countries [outside the United States] still use DDT; therefore food brought into the United States from these countries may contain DDT. The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) analyzes a wide variety of imported food items (coffee, tropical fruits, etc.) as well as domestic products to ensure the pesticide residues are below FDA tolerances. (Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry [ATSDR], 2002)

We can reduce the levels of pesticides that have been deposited on fruits and vegetables by washing these products before consuming them. Foods that are certified as organic are grown without synthetic pesticides and, according to some advocates, are safer than crops raised with synthetic pesticides; nevertheless, the safety of organic versus nonorganic produce is open to debate.

7.4 Environmental Hazards: Toxic Heavy Metals and Related Materials

Among the metals designated as toxic heavy metals are lead, mercury, cadmium, and chromium. Arsenic and asbestos (not heavy metals) also are elements that are hazardous to human health. Among the adverse health effects associated with heavy metals are birth defects, neurologic deficits, and potential for carcinogenicity.

Lead

A naturally occurring metallic element, lead is toxic to humans and animals (USEPA, 2013k). Before its phase-out was completed in 1996, lead from gasoline was disseminated widely into the environment by the combustion of motor fuels. Other lead exposure sources are lead-based paints, colorful painted ceramics and pottery, plumbing fixtures, lead-acid batteries, solder, and candy wrappers used in some countries. In addition, lead can be released into the air from metal smelters and can be present in air, water, and soil near metal refineries.

Woman with goggles, dust mask, and gloves, wiping a window from the inside with a sponge.

Cade Martin/CDC/Dawn Arlotta

A woman takes several precautions to protect against hazardous lead dust. Paint in homes constructed before 1978 may contain lead.

Today, human exposure from lead-based paints can occur in homes that were constructed before the 1978 ban on use of lead in household paints was adopted. Young children in older homes may risk exposure to lead when they eat paint chips peeling from walls.

Not only can lead in paint pose risks for home occupants and their children, but also lead-contaminated chipping and peeling paint in older homes can endanger house cleaners and remodelers. The use of personal protective equipment reduces dust inhalation; a damp sponge during cleaning reduces dust creation.

The health effects of lead exposure can be severe for children, pregnant women, and adults. Among children, lead ingestion can cause permanent brain damage, learning and behavior problems, growth retardation, and anemia. As a result of lead exposure, pregnant women can experience miscarriages and fetal growth retardation. Adults who are exposed to lead may experience adverse effects to the nervous system and cardiovascular system. For example, one of the adverse cardiovascular effects of lead exposure is increased blood pressure.

Mercury

Mercury is a naturally occurring element found in air, water, and soil. This heavy metal has several forms: elemental/metallic mercury, inorganic mercury compounds, and organic mercury compounds. At one time, medicines that contained mercury were used for treatment of syphilis and other diseases. Coal burning is the largest human-caused source of mercury emissions in the United States (USEPA, 2013m).

Health effects associated with exposure to elemental mercury include tremors, emotional changes, insomnia, and neurologic effects. Exposure can occur when vapors from elemental mercury are inhaled during occupational exposures that involve the use of mercury.

The organic form of mercury is methylmercury, which is created by the action of microorganisms that convert airborne mercury compounds deposited in water and on land into methylmercury (United States Geological Survey, 2013). Fish that consume these contaminated microorganisms develop elevated mercury levels. Birds and mammals that eat the fish further concentrate levels of methylmercury. In turn, top predators that eat these animals can develop high mercury levels. Most human exposure to methylmercury is through consumption of fish and shellfish. The levels of methylmercury are higher in some species of fish than in others, such as shark, swordfish, king mackerel, or tilefish (EPA, 2004); adults should minimize consumption of these species, and pregnant women and children should avoid them.

The human health effects of methylmercury can be severe. Among pregnant women, consumption of high levels of methylmercury endangers the developing nervous systems of their fetuses. Infants and children exposed to methylmercury can experience neurological impairment (USEPA, 2013n). Although methylmercury exposure among persons of all ages (including adults) can be deleterious, the developing nervous system of the fetus is at greater risk of harmful effects than is the nervous system of an adult.

Cadmium

Cadmium is a soft, silvery-white metal that exists in the Earth's crust. Usually, most types of cadmium in the environment are found in combination with oxygen, chlorine, and sulfur (ATSDR, n.d.). Typically, cadmium producers obtain the metal as a byproduct of smelting zinc, lead, and copper. Cadmium is used in the manufacture of plastics, pigments for paints, and parts for batteries. Metal plating operations also use cadmium.

Among the adverse health effects of high levels of exposure to cadmium are gastric upsets and lung irritation and lung injuries. Long-term, low-level doses of cadmium can damage the kidneys and cause kidney stones. Human exposures to cadmium result from ingestion of water and foods (e.g., shellfish and organ meats such as liver and kidneys) that contain cadmium and inhalation of airborne cadmium (e.g., from factories, in the workplace, and in cigarette smoke).

Chromium

Chromium is a gray, shiny, hard metal used in the manufacture of metal alloys and steel. Chromium occurs most commonly in the environment in two states (called valence states): trivalent chromium (Cr III), which exists naturally in the environment, and hexavalent chromium (Cr VI), which originates most typically from industrial processes (USEPA, 2013d). Trivalent chromium is a somewhat toxic substance that is an essential dietary element needed for metabolism. Sources of exposure to chromium (usually Cr III) are chromium-containing food, water, and air. Occupational exposure to chromium can come from industrial processes such as chrome plating and leather tanning. Some types of factories (e.g., cement manufacturing plants) can disseminate chromium into the atmosphere.

The toxicity of Cr VI is much higher than the toxicity of Cr III. The major target for Cr VI is the respiratory tract. Exposure can cause pneumonia, asthma, ulcerations in the nose, and other serious respiratory effects. When inhaled, hexavalent chromium is a human carcinogen associated with risk of lung cancer. Ingestion of large amounts of Cr VI may affect the liver, kidneys, and gastrointestinal system. A limited body of research suggests that exposure to Cr VI may have adverse reproductive effects, including complications of pregnancy and childbirth.

Photograph of a family eating takeout containing rice.

UpperCut Images/SuperStock

Although the FDA did not find evidence to warn against consumption, Consumer Reports reported rice samples to contain unsafe amounts of arsenic in a 2012 study.

Arsenic

Arsenic, which is an odorless and tasteless element, is called a semi-metal (Environmental Programs Directorate, n.d.). Typically, arsenic is found in combination with other elements in the form of either inorganic or organic arsenic, which is the less harmful of the two types. Sources of environmental arsenic are combustion of fossil fuels, the manufacture of chemicals, application of pesticides, releases from wood that has been treated with arseniccontaining preservatives, and cigarette smoke. In some areas of the world, contamination of drinking water with arsenic is the result of leaching from natural arsenic deposits and pollution from agriculture and industry.

The Environment, A Crucial Factor in Health

The environment is a crucial factor in a community's health.

Critical Thinking Question:

What types of environmental challenges are present in your area? What types of health concerns might these challenges translate to in the population?

One of the routes of human exposure to arsenic is ingestion of water and foods that contain arsenic. For example, in 2012, Consumer Reports magazine stated that samples of rice (organic rice baby cereal, rice breakfast cereals, brown rice, and white rice) intended for consumption in the United States contained arsenic—"many at worrisome levels" ("Arsenic in Your Food," 2012, p. 22). However, following this report, the FDA administration issued a statement to the effect that available data and scientific information did not warrant consumers' changes in their amounts of rice consumption (USFDA, 2012).

Arsenic exposure is associated with cancer of the bladder, lungs, skin, and other bodily sites (USEPA, 2012a). Other examples of the health effects of arsenic exposure are thickening and discoloration of the skin, gastric effects, and numbness of the extremities. Heavy exposure can result in paralysis and blindness.

Asbestos

A natural mineral fiber, asbestos was used in building construction, building materials, insulation, as a fire retardant, and in brake linings (USEPA, 2013l). Given its carcinogenic properties, most uses of asbestos are banned at present. However, asbestos may still be found in materials such as asbestos cement shingles and floor tiles that contained asbestos before its use was prohibited. Human exposure to asbestos can happen during home maintenance repair, remodeling, unsafe asbestos abatement procedures, and during demolition of older buildings.

Adverse pulmonary effects are one of the main consequences of asbestos exposure. The health effects of asbestos include lung disease (for example, asbestosis, a noncancerous lung disease), lung cancer, and mesothelioma, a rare type of cancer that can affect the lining of the chest and parts of the interior of the body such as the abdomen. In combination, asbestos and cigarette smoking work synergistically, meaning that smoking amplifies the adverse effects of asbestos exposure.

7.5 Environmental Hazards: Radiation

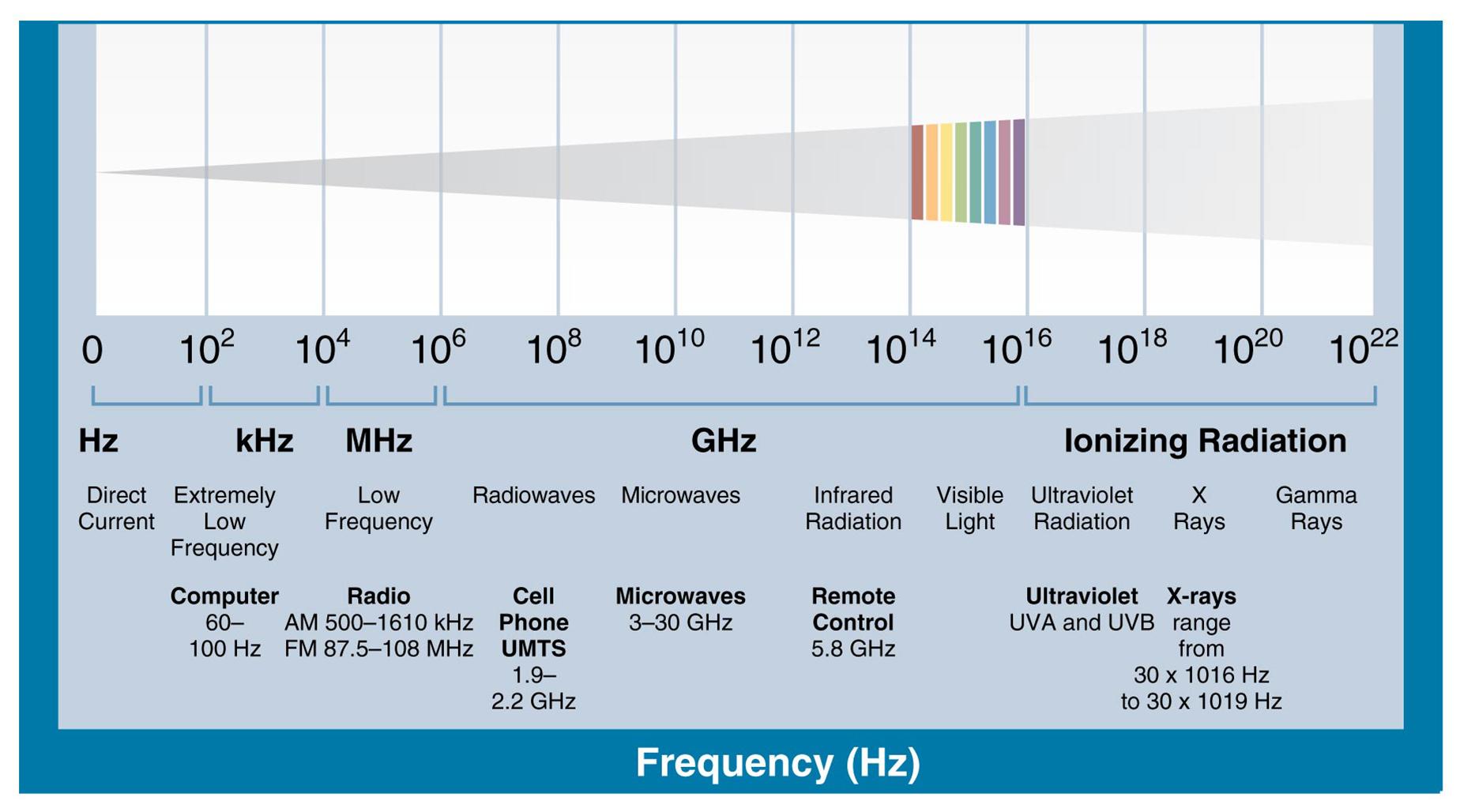

Generally speaking, radiation is subdivided into ionizing and nonionizing forms. Ionizing radiation has high levels of energy that are capable of damaging cells and DNA. Nonionizing radiation has lower levels of energy and is considered to be less harmful to human health, although it can cause some types of injuries such as burns, eye injuries, and, possibly, some types of cancer. The various types of nonionizing radiation, as well as ionizing radiation in the form of gamma rays and X-rays, make up the electromagnetic spectrum and can be arranged along the continuum of the spectrum, from low end to high end, depending on their energy levels. Figure 7.3 illustrates the electromagnetic spectrum with the location of various types of radiation on the spectrum.

Figure 7.3: The electromagnetic spectrum

Source: National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences. Electric and magnetic fields. Retrieved from http://www.niehs.nih.gov /health/topics/agents/emf/index.cfm

Not all levels of radiation are harmful—ionizing radiation is capable of damaging cells and DNA, while nonionizing radiation, though it can cause some types of injuries, is generally less harmful.

Ionizing Radiation

Ionizing radiation consists of either electromagnetic energy (e.g., gamma rays and X-rays) or particulate energy (e.g., alpha particles and beta particles). Alpha and beta particles and gamma rays are the products of decaying nuclear materials. Of these three forms of radiation, gamma rays are the most penetrating. X-rays are another highly penetrating form of ionizing radiation used in medical diagnostic procedures. Sources of human exposure to ionizing radiation include the following.

Nuclear Installations

Nuclear installations are current or decommissioned sites used for the manufacture of nuclear weapons and related devices, as well as electricity-generating plants fueled by nuclear materials. In the United States, weapons production facilities have been located in Oak Ridge, Tennessee; Hanford, Washington; and Rocky Flats, Colorado.

Several power plants fueled by nuclear materials have released ionizing radiation into the environment, and, in some cases, have caused widespread exposure of human populations. On March 26, 1979, a partial meltdown of a reactor core at the Three Mile Island plant in Pennsylvania caused the release of small amounts of radioactivity into the surrounding community. Less than a decade later, during April 1986, a nuclear meltdown at the power plant in Chernobyl, Ukraine, caused a massive dispersal of radioactive materials over the former Soviet Union and much of northern Europe. Since the Chernobyl disaster, the largest release of radioactivity was from the Fukushima nuclear power plant in Japan. This release followed reactor meltdowns and explosions at the generating installation subsequent to a severe earthquake and tsunami on March 11, 2011.

Karen Kasmauski/Science Faction/SuperStock

A resident of the Funari Old People's Home. This is one of two institutions in Hiroshima treating aging atomic bomb survivors. The other is the Atom Bomb Hospital.

Nuclear Weapons

Widely dispersed exposures of human populations to radioactivity occurred as a result of aboveground atmospheric testing of nuclear devices in the United States during the 1950s. Other countries that have performed aboveground tests have similarly exposed large populations to ionizing radiation. Toward the end of World War II, the United States detonated nuclear bombs over two Japanese cities, Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Among the adverse health effects of these exposures were their association with increased risk of breast cancer, particularly among women exposed between the ages of 10 and 19 years. The bombing of the two Japanese cities ushered in the Cold War and was followed by a 40-year nuclear arms race between the United States and the former Soviet Union.

Medical Exposures

Medical exposures account for one of the largest amounts of exposure of populations to ionizing radiation. Sources of exposure from medical procedures include X-ray machines, nuclear medicine, and radiation therapy.

Occupational Exposures

Individuals who may be occupationally exposed to ionizing radiation include certain medical personnel (e.g., radiation technologists and dental hygienists). Other occupationally exposed persons are research workers who use radioactive materials, employees of nuclear electricity-generating plants, and workers involved with the manufacture of nuclear devices. Their amount of exposure should be monitored carefully to ensure that they are not receiving excessive levels of radiation. The field of public health has a role in occupational settings with respect to assessment of health hazards among populations of workers, development of policies for worker protection, and provision of assurances that policies and assurances are effective. One of the leading federal regulatory agencies involved with assessment, policy development, and assurance for workers is the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA).

The Occupational Safety and Health Act (OSH Act) of 1970 was designed to protect employees in the work environment (OSHA, 2011). The intent of the OSH Act was

[t]o assure safe and healthful working conditions for working men and women; by authorizing enforcement of the standards developed under the Act; by assisting and encouraging the States in their efforts to assure safe and healthful working conditions; by providing for research, information, education, and training in the field of occupational safety and health; and for other purposes. (OSHA, n.d., para 1)

As part of the OSH Act, OSHA was created. OSHA is a federal regulatory agency that oversees worker health and safety and establishes and enforces protective standards for workers in diverse occupations in the United States.

Radon

According to the World Health Organization, "[r]adon gas is by far the most important source of ionizing radiation among those that are of natural origin" (Zeeb & Shannoun, 2009, p. 1). A product of the decay of uranium, radon is a radioactive gas that can accumulate in homes. Some geographic locations in the United States have high levels of naturally occurring radon gas, although the USEPA states that homes with high radon levels have been identified in every U.S. state, and adjacent homes can have radon levels that are very different (USEPA, 2013b).

The EPA has determined that some areas of the United States "have the potential to produce elevated levels of radon" and "recommends that all homes be tested for radon, regardless of geographic location or the zone designation of the county in which they are located" (USEPA, 1993, p. I-1). View the EPA Map of Radon Zones at http://www.epa.gov/radon/zonemap.html.

Review the Spotlight: Sources of Indoor Radon for sources of radon in homes. Homeowners can obtain assistance from qualified radon mitigators who are trained to modify homes and in most situations can abate excessive levels of radon gas. One method is to use a device that sucks out radon from beneath the foundations of homes and vents it above the house before the gas can enter the home.

Spotlight: Sources of Indoor Radon

The main source of indoor radon is radon gas infiltration from soil into buildings.

Rock and soil produce radon gas.

Building materials, the water supply, and natural gas can all be sources of radon in the home.

Basements allow more opportunity for soil gas entry than slab-on-grade foundations.

Showering and cooking can release radon into the air by aerosolizing household water (from a well) and burning natural gas.

Currently, testing is the only way to determine indoor radon concentration.

Source: Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry. (2010). ATSDR case studies in environmental medicine. Radon toxicity. Retrieved from http://www.atsdr.cdc.gov/csem/radon/radon.pdf

Radon is an extremely dangerous gas that is thought to be associated with about 20% of lung cancer cases in this country. It is the leading cause of lung cancer death among nonsmokers and the second most important cause of lung cancer in general (USEPA, 2013p). Smoking increases the risk of lung cancer among persons who have had radon exposure.

Other Forms of Exposure to Ionizing Radiation

Human exposures to ionizing radiation arise from cosmic rays that impinge upon the Earth from outer space. The Earth's atmosphere helps to filter cosmic rays and reduce their intensity. Also, in some parts of the world, geologic formations contain uranium and other radioactive elements that decay and emit radioactivity. These exposures are all from naturally occurring sources of ionizing radiation.

Nonionizing Radiation

Many electrical and electronic devices in our environment generate nonionizing radiation. Extremely low-frequency radiation in the range of 50 to 60 hertz (cycles per second) comes from electrical power lines, electrical substations, and appliances. These sources can produce low-frequency electromagnetic fields (EMFs). Concerns about exposure to low-frequency EMFs include a possible connection with leukemia risk (especially among children) reported in some studies, although the association was weak. Most communities require that homes be constructed away from high-tension overhead power lines in order to reduce exposures to electromagnetic fields. Among the other sources of nonionizing radiation are radio transmitters, microwave ovens, radar installations, and cellular phones. Refer back to Figure 7.3 for more examples of nonionizing radiation.

7.6 Examples of Environmentally Associated Diseases

Exposures to potentially hazardous agents such as toxic chemicals and metals, pesticides, and ionizing radiation are believed to be important for the etiology of many of the forms of environmentally associated morbidity (acute and chronic conditions, allergic responses, and disability) and mortality that occur in today's world. In the United States, environmental factors are implicated in many of the leading causes of death, including the five leading causes, which are diseases of the heart (heart disease), malignant neoplasms (cancer), cerebrovascular diseases (stroke), chronic lower respiratory diseases, and accidents (unintentional injuries). Similar trends for the causes of death associated with environmental risk factors are evident in many other developed countries. Examples of specific health outcomes studied in relationship to the environment are various forms of cancer (e.g., breast cancer and lung cancer), asthma and other lung diseases, cardiovascular disease, Parkinson's disease, and adverse reproductive effects.

Cancer

Cultura Limited/SuperStock

Environmental risk factors linked to cancer include excessive sun exposure.

Carcinogens present in the environment are suspected links to many forms of cancer in humans. The term carcinogen is used to describe a chemical or physical agent that causes cancer (USEPA, 2013i). Some of the potentially toxic chemicals and elements identified as possible human carcinogens include organic pesticides, solvents, cadmium, and arsenic, as well as other chemicals that may be present in the air, foods, and water supply.

The National Cancer Institute (NCI) and the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (NIEHS) state that

[e]xposure to a wide variety of natural and man-made substances in the environment accounts for at least two thirds of all the cases of cancer in the United States. These environmental factors include lifestyle choices like cigarette smoking, excessive alcohol consumption, poor diet, lack of exercise, excessive sunlight exposure, and sexual behavior that increases exposure to certain viruses. Other factors include exposure to certain medical drugs, hormones, radiation, viruses, bacteria, and environmental chemicals that may be present in the air, water, food, and workplace. (National Cancer Institute and NIEHS, 2003, p. 1)

Respiratory Diseases

Respiratory diseases include asthma, pneumonia, influenza, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), and impaired lung function. Associated environmental exposures are air pollution, secondhand tobacco smoke, allergens, and molds.

Asthma is "a chronic (long-term) disease that inflames and narrows the airways. Asthma causes recurring periods of wheezing (a whistling sound when you breathe), chest tightness, shortness of breath, and coughing. The coughing often occurs at night or early in the morning" (National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute [NHLBI], 2012). Asthma triggers are factors that can cause asthma symptoms to appear or to worsen. Examples of asthma triggers are allergens (for example, dust and dust mites, animal fur, and cockroaches), cigarette smoke, air pollution, certain medicines, colds, and physical activity. Asthma is a prevalent lung disease that affects children and adults. An estimated 25 million people (1 in 12 people) in the United States in 2009 had asthma (CDC, 2011a). During the same year, the prevalence of asthma was approximately 8% among adults and 10% among children.

Reproductive Health Effects

The scope of reproductive health includes health outcomes (e.g., diseases and conditions) related to the functioning of the reproductive systems of males and females during all life stages. Exposures to exogenous environmental factors such as chemicals, heavy metals, and other toxins have been linked to reproductive impairments and adverse birth outcomes. According to the NIEHS, these

include birth defects, developmental disorders, low birth weight, preterm birth, reduced fertility, impotence, and menstrual disorders. Research has shown that exposure to environmental pollutants [such as lead and mercury] may pose the greatest threat to reproductive health. Exposure to lead is associated with reduced fertility in both men and women, while mercury exposure has been linked to birth defects and neurological disorders. A growing body of evidence suggests that exposure to endocrine disruptors, chemicals that appear to disrupt hormonal activity in humans and animals, may contribute to problems with fertility, pregnancy, and other aspects of reproduction. (NIEHS, 2012, para. 1)

As noted earlier in the chapter, one of the most common sources of exposure of the population to mercury is ingestion of certain species of fish and shellfish that contain methylmercury. Pregnant women who consume seafood that contains methylmercury can increase the risk of birth defects in their developing fetuses.

Brain Impairments

Brain impairments that may be related to environmental factors include autism and impaired cognitive development. Although the causes of autism are not well understood, research points to a possible relationship between genetic factors and environmental exposures, particularly during pregnancy. Impaired cognitive development is related to children's exposure to heavy metals such as lead. Environmental lead exposure is linked to reduced cognitive performance and other neurologic deficits among children.

Parkinson's Disease

The NIEHS defines Parkinson's disease as "a chronic neurodegenerative disease, the second most prevalent such disorder after Alzheimer's disease" (NIEHS, 2005, p. 1). The condition is characterized by loss of motor coordination—for example, difficulty in moving one's limbs and hands. Parkinson's disease, which is an age-related condition, affects approximately one million people in North America; the annual incidence is about 50,000 cases. Some of the environmental factors hypothesized to be associated with Parkinson's disease are pesticide use, herbicide exposure, consumption of well water, and residence near industrial facilities. Research has demonstrated such associations only; their causal mechanisms, if any, are largely unknown at this time:

Scientists generally agree that most cases of Parkinson's disease (PD) result from some combination of nature and nurture—interaction between a person's underlying genetic make-up, and his or her life activities and environmental exposures. A simple way to describe this is that "genetics loads the gun and environment pulls the trigger." In this formulation, "environment" has a very broad meaning—that is, it refers to any and all possible causes other than those that are genetic in origin. (Tanner, 2013, para 1)

7.7 Public and Community Environmental Protection

From the early 1900s to the present, life expectancy in the United States has almost doubled. This improvement in life expectancy has come about, in part, as a result of positive environmental changes that occurred during the past century. Among these positive changes are better sanitation, cleaner water, improved air quality, attention to the safe use of chemicals, and prevention of unsafe behaviors. For example, in recent years, lead has been taken out of gasoline, some potential carcinogens have been removed from pharmaceuticals, a number of toxic chemicals have been eliminated from products used in the home and workplace, and pregnant women and other consumers have been advised not to consume fish that might contain high levels of mercury. In the United States, the Healthy People 2020 program (see Spotlight: Healthy People 2020) reflects a government focus on public health, outlining national goals and objectives established by the United States Department of Health and Human Services.

Spotlight: Healthy People 2020

Giving recognition to the importance of the environment, Healthy People 2020 specifies 24 objectives regarding environmental health. These objectives pertain to outdoor air quality, surface and groundwater quality, toxic substances and hazardous wastes, homes and communities, infrastructure and surveillance, and global environmental health.

Outdoor Air Quality

Reduce the number of days the Air Quality Index (AQI) exceeds 100, weighted by population and AQI

Increase use of alternative modes of transportation for work (for example, bicycling, walking, use of mass transit, and telecommuting)

Reduce air toxic emissions to decrease the risk of adverse health effects caused by mobile, area, and major sources of airborne toxics

Water Quality

Increase the proportion of persons served by community water systems who receive a supply of drinking water that meets the regulations of the Safe Drinking Water Act

Reduce waterborne disease outbreaks arising from water intended for drinking among persons served by community water systems

Reduce per capita domestic water withdrawals with respect to use and conservation

Increase the proportion of days that beaches are open and safe for swimming

Toxics and Waste

Reduce blood lead levels in children

Minimize the risks to human health and the environment posed by hazardous sites

Reduce pesticide exposures that result in visits to a health care facility

Reduce the amount of toxic pollutants released into the environment

Increase recycling of municipal solid waste

Healthy Homes and Healthy Communities

Reduce indoor allergen levels

Increase the proportion of homes with an operating radon mitigation system for persons living in homes at risk for radon exposure

Increase the proportion of new single-family homes (SFH) constructed with radon-reducing features, especially in high-radon-potential areas

Increase the proportion of the Nation's elementary, middle, and high schools that have official school policies and engage in practices that promote a healthy and safe physical school environment

(Developmental) Increase the proportion of persons living in pre-1978 housing that has been tested for the presence of lead-based paint or related hazards

Reduce the number of U.S. homes that are found to have lead-based paint or related hazards

Reduce the proportion of occupied housing units that have moderate or severe physical problems

Infrastructure and Surveillance

Reduce exposure to selected environmental chemicals in the population, as measured by blood and urine concentrations of the substances or their metabolites

Improve quality, utility, awareness, and use of existing information systems for environmental health

Increase the number of States, Territories, Tribes, and the District of Columbia that monitor diseases or conditions that can be caused by exposure to environmental hazards (for example, lead poisoning, pesticides, arsenic, and carbon monoxide)

Reduce the number of new schools sited within 500 feet of an interstate or Federal or State highway

Global Environmental Health

Reduce the global burden of disease due to poor water quality, sanitation, and insufficient hygiene

Source: Adapted from HealthyPeople.gov. (2013). Retrieved from http://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/topicsobjectives2020 /objectiveslist.aspx?topicId=12

Drinking Water

In the developed countries of Europe and North America, one of the greatest contributions to community health has been the availability of safe drinking water. During the 20th century, treatment of drinking water on these continents was responsible for drastic reductions in the numbers of cholera and typhoid cases (CDC, 2011f).

Presently, water-related diseases, the second leading cause of childhood mortality in the world, are associated with unsafe drinking water, poor sanitation, and lack of personal hygiene. Each year, worldwide, water-related diseases are responsible for the deaths of 1.5 million children under the age of 5. Estimates suggest that improvements in the quality of water and levels of sanitation and hygiene in less developed areas of the world could prevent almost 10% of the global burden of disease and about 6% of all deaths (CDC, 2012).

Sources of Freshwater

In the United States, the sources of most water for human consumption are underground aquifers or groundwater from lakes, rivers, and streams. Underground aquifers are subterranean formations that contain bodies of water that is pumped out for use by the community.

The Earth's supplies of freshwater for human consumption are finite. In many of the world's countries, the water supply is inadequate. For example, water sources in some Middle Eastern countries and in arid sections of the United States are under stress. Factors limiting the available water supply are population growth, climate change, and competition for resources by various users (USEPA, 2012d).

Safe Drinking Water Act

The goal of the Safe Drinking Water Act (SDWA) is to ensure the safety of potable water used by residents of the United States. In 1974, Congress passed the original SDWA, which was amended in 1986 and 1996 (USEPA, 2012c). The SDWA protects drinking water and its sources (e.g., rivers, lakes, reservoirs, springs, and wells). The EPA is charged with the responsibility of setting water quality standards and monitoring these standards. The responsibilities of EPA for water quality extend to states, localities, and water suppliers.

The EPA regulates the quality of water from public drinking water systems, which provide water to about 90% of the U.S. population. The EPA defines a public drinking water system as "a system for the provision to the public of water for human consumption through pipes or other constructed conveyances, if such a system has at least 15 service connections or regularly serves at least twenty-five individuals" (USEPA, 2013o).

Treatment of Potable Water

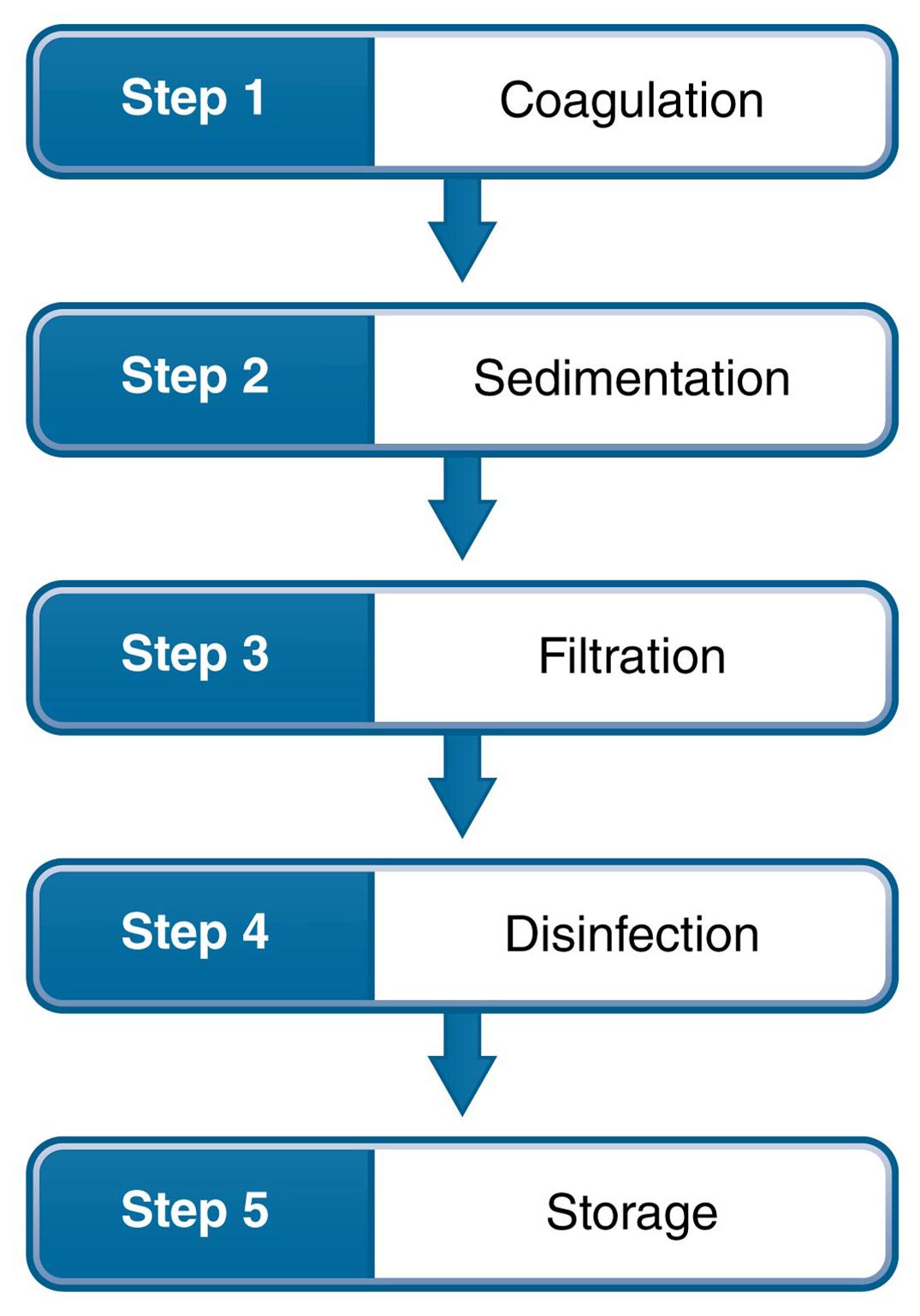

Before it can be distributed to the community, water must be treated to improve aesthetic and hygienic qualities. The stages involved in water treatment are shown in Figure 7.4. Initially, water treatment employs coagulation and sedimentation to remove solids and suspended materials. Then the water is further processed through filtration and disinfection with chlorine or other chemicals and stored for distribution to customers.

Figure 7.4: Steps involved in treatment of water for use by consumers

Innovations in Water Reuse

Given the increasing stresses on limited water supplies, reuse of water is one approach for increasing the amount available for various uses. Not all water (e.g., water used for landscape irrigation, flushing toilets, and some industrial processes) needs to be of drinking water quality. Treated wastewater can be reused for landscape irrigation and other less demanding purposes such as flushing toilets.

Artificial aquifer recharge is a method for injection of treated water, surface water, and storm water into aquifers to increase available drinking water. Desalination—treatment of seawater and brackish water to remove salts and other contaminants—can make these nonpotable waters suitable for human consumption. Desalination holds promise for increasing water supplies but is costly and can have adverse environmental impacts such as the disposal of salts removed from the water. Still another method for increasing water availability is storing storm water for future use in depleted aquifers and cisterns.

Raymond Forbes/age fotostock/SuperStock

Deer Island Water Treatment facility, the second largest treatment plant in the United States, protects against sewage pollution in Boston, Massachusetts.

Wastewater Treatment

Wastewater, also called sewage, requires treatment in order to protect surface water for drinking and human contact during water sports. The consequences of discharging untreated sewage into waterways can include microbial contamination, reductions in levels of dissolved oxygen, proliferation of algae, and fish kills (USEPA, 2004).

Making wastewater safe for discharge into the environment involves primary and secondary treatment, and in some instances, advanced treatment. Primary treatment involves removal of large solids. During secondary treatment, elimination of as much as 90% of organic material is achieved. Chlorine and ultraviolet radiation may be used to deactivate microorganisms in the sewage. Advanced treatment removes contaminants such as nitrogen and phosphorous, which can cause the overgrowth of algae when wastewater is discharged into lakes and streams.

Water Quality and Impervious Surfaces

Impervious surfaces, which cover much of the built environment, are human-created barriers to rainwater. These barriers prevent rainwater from being absorbed naturally by the soil and, instead, cause the water to flow into the streams, lakes, and oceans. There it can raise pollution levels and have other harmful consequences. "Impervious surfaces can be concrete or asphalt, they can be roofs or parking lots, but they all have at least one thing in common—water runs off of them. And with that runoff comes a host of problems" (Frazer, 2005, p. A457).

Estimates indicate that in this country, impervious surfaces cover a total area that is almost the size of Ohio. On impervious surfaces such as parking lots, a variety of pollutants and debris can accumulate. For example, substances from cars (tire and brake dust, metal particles, and oil and chemicals) build up over time. In addition, a wide variety of materials including carelessly discarded used motor oil and toxic chemicals, animal feces, and garbage collects on many urban streets and sidewalks. Also, airborne pollutants have the capacity to accumulate on rooftops. All of these materials are prone to be washed into bodies of water such as coastal oceans during a storm. Urban runoff into the ocean, which is a problem of great concern for Southern California and other U.S. regions near the coasts, can raise levels of harmful bacteria, release toxic chemicals, and introduce nitrogen-containing fertilizers that cause overgrowth of algae. This runoff can make the marine environment unsafe for swimmers and surfers and harm aquatic life. Moreover, impervious surfaces increase the likelihood of flooding during heavy rainfalls.

Hazardous Waste Disposal

Disposal of municipal solid wastes (garbage) is another essential feature of maintaining a sanitary and healthful environment. In addition to being offensive, garbage that is allowed to accumulate on city streets attracts rodents, insects, and other disease vectors. During 2010, about a quarter billion tons of trash was generated in the United States. On average, each person in the United States produces about 4½ pounds of trash daily. More than a quarter of this trash is paper and paperboard.

Available disposal sites for municipal solid wastes are becoming ever more limited and are being filled to capacity. Three methods for addressing the solid waste problem and sending smaller amounts to disposal sites are source reduction (use of more efficient packaging), recycling useful materials in trash, and composting organic materials in waste. Currently, about one-third of municipal wastes are recycled or composted.

Some wastes are hazardous, meaning that they can injure human beings and wildlife. They can also seep into aquifers and groundwater, endangering the water supply and harming aquatic life. Manufacturing processes and products for home use (e.g., paints, batteries, compact fluorescent light bulbs, and used containers of insecticides) can generate hazardous wastes. Careful recycling and disposal in specially designed disposal sites are required in order to protect the community from hazardous wastes.

Hazardous Waste Sites: Superfund

Concerns about the health and environmental effects of abandoned hazardous waste sites led to the Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation and Liability Act (CERCLA) of 1980. For example, one of the most notorious hazardous waste sites in the United States was Love Canal in Niagara Falls, New York. The Hooker Chemical & Plastics Corporation had buried numerous drums filled with chemicals in the site, which was later covered over and used as land for homes. Residents of the new homes complained of various adverse health effects including miscarriages and birth defects. The CERCLA law was a response to the potential dangers posed by Love Canal and other hazardous waste sites. Superfund refers to the fund established by CERCLA as well as the environmental program that deals with hazardous waste sites. CERCLA "allows the EPA to clean up such sites and to compel responsible parties to perform cleanups or reimburse the government for EPA-lead [sic] cleanups" (USEPA, 2013q).

The term brownfield is a designation related to hazardous waste sites that are planned for rehabilitation. Brownfields are defined as

real property, the expansion, redevelopment, or reuse of which may be complicated by the presence or potential presence of a hazardous substance, pollutant, or contaminant. Cleaning up and reinvesting in these properties protects the environment, reduces blight, and takes development pressures off green spaces and working lands. (USEPA, 2013c, para. 3)

In contrast with brownfields are greenfield sites, which are "an area of [uncontaminated] agricultural or forest land, or some other undeveloped site earmarked for commercial development or industrial projects" (BusinessDictionary.com, 2010, para. 1).

Environmental Emergencies and Hazardous Materials

Hazardous materials include toxic chemicals, radioactive substances, and biohazards. They may be found in a wide variety of settings (for example, school laboratories, hospitals, factories, chemical plants, and military bases). They may even be associated with home labs involved in the illegal production of drugs such as methamphetamine. Hazmat is a shortened term for "hazardous plus materials" that is used to refer to these types of materials (eHow, 2013).

Hazardous materials can endanger communities and the environment as a result of explosions in installations where they are being used, unintentional chemical spills, and mishaps during transportation. Personnel who arrive first on the scene—called first responders— require special training and equipment to deal with hazardous agents. Many communities in the United States have formed hazmat teams that protect the public, limit the effects of a toxic release, and cope with the immediate causes and effects of a hazardous waste emergency. The hazmat team may arrive in a special truck that has been equipped for containing a variety of hazardous materials. When facing unusual events such as a terrorism event, a local hazmat team might request assistance from outside agencies.

Food Safety

Each year about one out of six persons in the United States is sickened by foodborne illness, which also causes 128,000 hospitalizations and 3,000 deaths (CDC, 2013).

Sometimes national or international in scope, foodborne illness incidents can rivet the attention of the public and the media and result in widespread deaths and illnesses. A hepatitis A outbreak in late 2003 at Chi-Chi's Mexican restaurant northwest of Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, resulted in three deaths and almost 600 cases of illness. The hepatitis A virus was linked to green onions, believed to have been imported from Mexico (USATODAY.com, 2003). In August and September 2006, a multistate outbreak of foodborne illness caused by the bacterium Escherichia coli infected 183 persons in 26 states and was associated with several deaths. The infection was traced to raw spinach from California (CDC, 2006).

Protection of food safety, one of the cornerstones of community health, encompasses the food production chain, surveillance of foodborne outbreaks, investigation and control of outbreaks, and inspection of retail food establishments. At any point during the production of foodstuffs, contamination can occur. The food production chain involves food "production, processing, or preparation" (CDC, 2011d, para 1).

When a foodborne outbreak occurs, any of several levels of government may become involved: federal, state, and local (CDC, 2011c). Federal agencies include the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the Food and Drug Administration, and the Food Safety and Inspection Service (FSIS), which is a branch of the United States Department of Agriculture. The CDC investigates large, severe, or unusual outbreaks. The CDC also operates a surveillance system known as the Foodborne Disease Active Surveillance Network (FoodNet) for monitoring the occurrence of foodborne disease (CDC, 2011b).

A landmark act passed by Congress and designed to assure the safety of foods, beverages, and drugs in this country was the 1906 Pure Food and Drugs Act. This act prohibited "interstate commerce of misbranded and adulterated foods, drinks, and drugs" and "was spurred by shocking disclosures of the use of poisonous preservatives and dyes in foods, documented in the press and featured in Upton Sinclair's novel The Jungle" (USFDA, 2013b, para 5). The formation of the present-day Food and Drug Administration coincided with the 1906 act, although the agency did not use the name "Food and Drug Administration" until 1930 (FDA, 2013a). In 1938, Congress passed the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act, which superseded the 1906 act.

Another agency responsible for food safety is the 150-year-old United States Department of Agriculture (USDA). The USDA was created by an act of Congress and signed into law by President Lincoln (USDA, 2012a). The USDA has a wide scope that includes assuring the safety, wholesomeness, and labeling of meat, poultry, and eggs from commercial sources (USDA, 2012b).