HCA415 Community & Public Health-WK2-A1

Chapter 9 Mental Health

9.1 Introduction

Mental disorders are common adverse health outcomes that affect almost half a billion persons on the globe, according to the World Health Organization (WHO). In the United States, more than one-quarter of the adult population is afflicted with mental illnesses during any given year. Mental disorders represent highly salient health issues for the community with respect to their associated burdens, economic costs, and adverse impacts upon families and society. Some of the observable concomitants of mental illness in the United States are homelessness, suicide among returning war veterans, and incarceration of persons who are mentally ill. Also, persons who have severe mental disorders may face stigmatization and ostracism, although these responses are lessening as society becomes more enlightened about the nature of mental illness.

Chapter 9 provides an overview of the global and national prevalence of mental disorders and gives alternative definitions of the terms mental health and mental illness. Data on the epidemiology of mental disorders reveal substantial variations according to age, sex, race, and socioeconomic status. Examples of mental disorders discussed in this chapter are anxiety disorder and its subtypes, bipolar disorders, depression, schizophrenia, and suicide. Although the causes of mental illness are not understood fully, some disorders are known to be associated with family, social, and environmental influences; various stressful situations and events; experience of trauma; and—in some instances—genetic predisposition. In the past, the treatment of people who had mental disorders was quite deplorable and involved such practices as long-term institutionalization, isolation in locked cells, and physical restraints. Ethical consideration of the mentally ill was also not a high priority in previous eras. Today, clinicians, public health and community health providers, and mental health researchers struggle with this issue.

Later advances in the treatment of the mentally ill included the use of psychotropic medications and small-scale treatment facilities (e.g., community mental health centers). During the 1950s, a movement to deinstitutionalize the mentally ill came into effect. The causes of this movement included crowding and poor conditions within institutions, and the hope that the introduction of psychotropic drugs would now allow patients to function in their communities. As a result, numerous large state mental institutions were closed. At present, many persons who have debilitating mental illness are unable to gain access to treatment. Some of these individuals exhibit inappropriate behaviors, or even commit crimes and become incarcerated—in this case, prisons become de facto treatment facilities for the mentally ill in America. At the same time, advances in the treatment of mental disorders have enabled many persons with mental illnesses to lead productive lives. In an optimal sense, clinical treatment combined with community-based measures for prevention and maintenance of mental health are most effective in reducing relapse of current cases as well as the occurrence of new cases in society.

Burden of Mental Illness

Mental illness is a prevalent condition globally, as well as in the United States, with severe economic impacts and adverse social consequences. Approximately 450 million cases of mental illness exist worldwide, according to WHO (2010). The National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) states that mental disorders are frequent health issues in the United States. "An estimated 26.2% of Americans ages 18 and older—about one in four adults—suffer from a diagnosable mental disorder in any given year" (n.d.p, para. 1). Given their prevalence, mental illnesses are among the most frequent sources of disability in the United States (USDHHS, 2013; CDC, 2011e). However, the burden of severe mental illness—6% of the population—is much smaller than the total of all diagnosable mental disorders (NIMH, n.d.p).

Economic Costs of Mental Illness

The economic costs of mental illness include direct expenses, such as those associated with treatment, and indirect costs, such as lost worker productivity and payments for government-funded disability benefits. The NIMH states that conservative estimates of these costs in 2002 were more the $300 billion per year for the 6% of the population with serious mental illnesses (n.d.o).

Design Pics/SuperStock

What may come across as erratic or strange behavior to the general public are commonly symptoms of mental illness among the homeless.

Impacts of Mental Illness

Mental disorders, particularly serious ones, are linked to disability, stigmatization, homelessness, and incarceration. In terms of homelessness, the National Alliance on Mental Illness (NAMI) estimates that nearly one-third of the U.S. homeless population has a mental illness (2004). Approximately 20% to 25% of the homeless population has a severe mental illness (National Coalition for the Homeless, 2009). Insufficient availability of treatment services for mental illness contributes to chronic homelessness. In addition, people with severe mental illnesses may be unable to perform the essential tasks of everyday life. The loss of functional capacity in concert with lessened ability to maintain gainful employment is among the causes of homelessness.

As a result of committing major or minor offenses, mentally ill persons come to the attention of law enforcement on some occasions and may be incarcerated. In other instances, incarceration may be the consequence of bizarre behavior that is perceived as threatening. The Department of Justice reports that two-thirds of jail inmates (64.2%) demonstrate mental health problems (NIMH, n.d.g). At present, in many areas of the country, the nation's jails provide more treatment than mental health treatment centers for mental disorders (NPR, 2011).

One of the groups that are impacted by mental disorders is composed of military veterans who are returning to the country with serious mental health issues such as post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), major depression, and anxiety, as well as substance abuse issues (United States National Library of Medicine, n.d.). One of the consequences of mental illnesses among returning veterans is an increased suicide rate (APA, n.d.). Many veterans are forced to cope with long-term unemployment, which can add to their sense of distress and hopelessness.

Mental disorders and how to care for those who suffer from them has long been a dilemma within the field of medical ethics. Even today, there is still the tendency for our society and its laws to discriminate against those with mental disorders in ways that those with physical disorders do not have to deal with. Historically, "many societies have regarded patients with mental illness as a threat to those around them rather than as people in need of support and care" (World Medical Association [WMA], 2013, para. 1). Currently, improvements in therapeutic treatment have increased the quality of care available to those suffering from mental illness. Modern treatments, including therapy and psychiatric drugs can "result in patient outcomes ranging from complete alleviation of symptoms to long remissions" (WMA, 2013, para. 2). Given this possibility of successful treatment, the WMA advises that "those with mental illness should be viewed, treated and granted the same access to care as any other medical patient (WMA, 2013, para. 3). Visit http://www.wma.net/en/30publications/10policies/e11/ for the WMA's list of ethical principles concerning patients with mental illness.

Definitions of Mental Health Terms

This section defines the following terms: mental health, mental illness, and serious mental illness. In addition, we present information on methods for the classification of mental disorders.

Mental Health

Mental health status is connected closely to physical health. Positive mental health status is crucial to the ability to lead a fulfilling life. The WHO defines mental health as

a state of well-being in which an individual realizes his or her own abilities, can cope with the normal stresses of life, can work productively and is able to make a contribution to his or her community. In this positive sense, mental health is the foundation for individual well-being and the effective functioning of the community. (WHO, 2010, para. 2)

Three hallmarks—emotional well-being, psychological well-being, and social well-being—characterize mental health. Refer to Spotlight: Mental Health Indicators for more information regarding these indicators.

Spotlight: Mental Health Indicators

Maslow's Hierarchy of Needs

Jupiterimages/Thinkstock

Individuals who volunteer can be seen demonstrating the three facets of well-being—a sense of purpose, a closeness to others, and a feeling of personal growth.

Maslow's hierarchy of needs is a psychological theory proposed by Abraham Maslow in his paper "A Theory of Human Motivation" (1943). His theories focused on describing the stages of growth and motivation in humans. The key stages, in ascending order, are basic needs, safety needs, social needs, esteem needs, and self-actualization. Maslow described a process wherein humans progress through these stages as one set of needs is satisfied and a new set becomes the motivating factor. Maslow's hierarchy of needs is usually portrayed as a pyramid with the largest, most basic levels of needs at the bottom and the need for self-actualization at the top. So mental health might be measured by an individual's ability to satisfy the needs on the bottom and middle of the pyramid and to work toward satisfying the needs at the top.

Other forms of psychological health are as follows:

Emotional well-being: Perceived life satisfaction, happiness, cheerfulness, peacefulness

Psychological well-being: Self-acceptance, personal growth including openness to new experiences, optimism, hopefulness, purpose in life, control of one’s environment, spirituality, self-direction, and positive relationships

Social well-being: Social acceptance, beliefs in the potential of people in society as a whole, personal self-worth and usefulness to society, sense of community

Source: Adapted from Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Mental health. Mental health basics. http://www.cdc.gov/mentalhealth/basics.htm

Mental Illness

The definition of mental illness is "collectively . . . all diagnosable mental disorders. Mental disorders are health conditions that are characterized by alterations in thinking, mood, behavior (or some combination thereof) associated with distress, and/or impaired functioning" (USDHHS, 1999, p. 5). NAMI states that "mental illnesses are medical conditions that disrupt a person's thinking, feeling, mood, ability to relate to others and daily functioning" (n.d.b, para. 1). Therefore, a mental illness is a condition that affects one's thoughts and emotions and interferes with the ability to function normally and enjoy daily life. As with many diseases, mental illness can be identified on a continuum in which some cases are mild and others are more severe. Many individuals with mental disorders show no outward signs of their symptoms. Others may show more obvious outward symptoms, such as agitation or confusion.

Serious mental illness (SMI) is defined as "having at some time in the past year a diagnosable mental, behavioral, or emotional disorder . . . that resulted in functional impairment that substantially interfered with or limited one or more major activities" (Epstein, Barker, Vorburger, & Murtha, 2002, p. 5). Mental illness and mental health can be thought of as points that fall on a continuum, rather than as exact opposites:

Somewhere in the middle of that continuum are "mental health problems," which most people have experienced at some point in their lives. The experience of feeling low and dispirited in the face of a stressful job is a familiar example. The boundaries between mental health problems and milder forms of mental illness are often indistinct, just as they are in many other areas of health. Yet at the far end of the continuum lie disabling mental illnesses such as major depression, schizophrenia, and bipolar disorder. Left untreated, these disorders erase any doubt as to their devastating potential. (USDHHS, 2001, p. 5)

Healthy People 2020 Goals and Objectives for Mental Health

Healthy People 2020 acknowledges the significance of mental illness for America in terms of the associated burden from all types of disorders, as well as serious disorders among adults and children in this country. The document also expresses the essential contribution that positive mental health status makes to optimal family dynamics, satisfying interpersonal relationships, and a generally rewarding life. The Healthy People 2020 goal with respect to mental health and mental disorders is to "improve mental health through prevention and by ensuring access to appropriate, quality mental health services" (USDHHS, n.d.b, para. 1). Health Care in Action: Healthy People 2020 Topic Area: Mental Health and Mental Disorders states the Healthy People 2020 objectives in these topic areas.

Health Care in Action: Healthy People 2020 Topic Area: Mental Health and Mental Disorders

Mental Health Status Improvement

MHMD–1: Reduce the suicide rate.

Target: 10.2 suicides per 100,000 population.

Baseline: 11.3 suicides per 100,000 population occurred in 2007.

Target setting method: 10 percent improvement.

Data source: National Vital Statistics System–Mortality (NVSS–M), CDC, NCHS.

MHMD–2: Reduce suicide attempts by adolescents.

Target: 1.7 suicide attempts per 100 population.

Baseline: 1.9 suicide attempts per 100 population occurred in 2009.

Target setting method: 10 percent improvement.

Data source: Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance System (YRBSS), CDC, NCCHPHP.

MHMD–3: Reduce the proportion of adolescents who engage in disordered eating behaviors in an attempt to control their weight.

Target: 12.9 percent.

Baseline: 14.3 percent of adolescents engaged in disordered eating behaviors in an attempt to control their weight in 2009.

Target setting method: 10 percent improvement.

Data source: Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance System (YRBSS), CDC, NCCDPHP.

MHMD–4: Reduce the proportion of persons who experience major depressive episodes (MDEs).

MHMD–4.1 Reduce the proportion of adolescents aged 12 to 17 years who experience major depressive episodes (MDEs).

Target: 7.4 percent.

Baseline: 8.3 percent of adolescents aged 12 to 17 years experienced a major depressive episode in 2008.

Target setting method: 10 percent improvement.

Data source: National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH), SAMHSA.

MHMD–4.2 Reduce the proportion of adults aged 18 years and older who experience major depressive episodes (MDEs).

Target: 6.1 percent.

Baseline: 6.8 percent of adults aged 18 years and older experienced a major depressive episode in 2008.

Target setting method: 10 percent improvement.

Data source: National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH), SAMHSA.

Treatment Expansion

MHMD–5: Increase the proportion of primary care facilities that provide mental health treatment onsite or by paid referral.

Target: 87 percent.

Baseline: 79 percent of primary care facilities provided mental health treatment onsite or by paid referral in 2006.

Target setting method: 10 percent improvement.

Data source: Uniform Data System (UDS), HRSA.

MHMD–6: Increase the proportion of children with mental health problems who receive treatment.

Target: 75.8 percent.

Baseline: 68.9 percent of children with mental health problems received treatment in 2008.

Target setting method: 10 percent improvement.

Data source: National Health Interview Survey (NHIS), CDC, NCHS.

MHMD–7: Increase the proportion of juvenile residential facilities that screen admissions for mental health problems.

Target: 64 percent.

Baseline: 58 percent of juvenile residential facilities screened admissions for mental health problems in 2006.

Target setting method: 10 percent improvement.

Data source: Juvenile Residential Facilities Census (JFRC), DOJ, OJJDP.

Source: Healthy People 2020

9.2 Epidemiology of Mental Disorders

Mental disorders vary systematically in the population of the United States according to demographic and geographic characteristics such as sex, age, race, and state of residence. Disparities in availability of treatment services for mental disorders are noteworthy for community health. For example, some racial and ethnic groups, as well as persons with low-income levels, have less access to mental health services than other groups.

Disparities in Mental Health Care

Current data shows that there are disparities in access to mental health care, and in the quality of care, across racial and ethnic groups. As documented in "Mental Health: A Report of the Surgeon General" (USDHHS, 1999) and its supplement, "Mental Health: Culture, Race, and Ethnicity" (USDHHS, 2001):

Members of racial and ethnic minority groups have less access to mental health services than do their white counterparts, are less likely to receive needed care, and are more likely to receive poor quality of care when treated. Minorities in the United States are more likely than white Americans to delay or fail to seek mental health treatment. Two studies examining trends in mental health care, using the Institute of Medicine definition of disparities found no progress toward eliminating disparities in mental health care provided in either primary care or psychiatric settings. (USDHHS, 2001)

The causes of such disparities are multifaceted. Part of the differential may lie in differences in access in minority communities, and also lower rates of health insurance coverage in these communities. In addition, more minorities live in inner cities, and in some cases these areas are served by lower-quality facilities and services.

Prevalence of Any Disorder

Two common methods for stating the prevalence of mental disorders are lifetime prevalence (ever having a disorder during one's lifetime) and 12-month prevalence (experiencing a disorder during the past year). Each type of prevalence estimate gives a somewhat different view of a mental disorder. The lifetime prevalence is greater than the 12-month prevalence for those conditions for which recovery is possible. Individuals who were afflicted with the disorder at some previous time in their lives may no longer have the disorder when they are assessed by an annual prevalence survey.

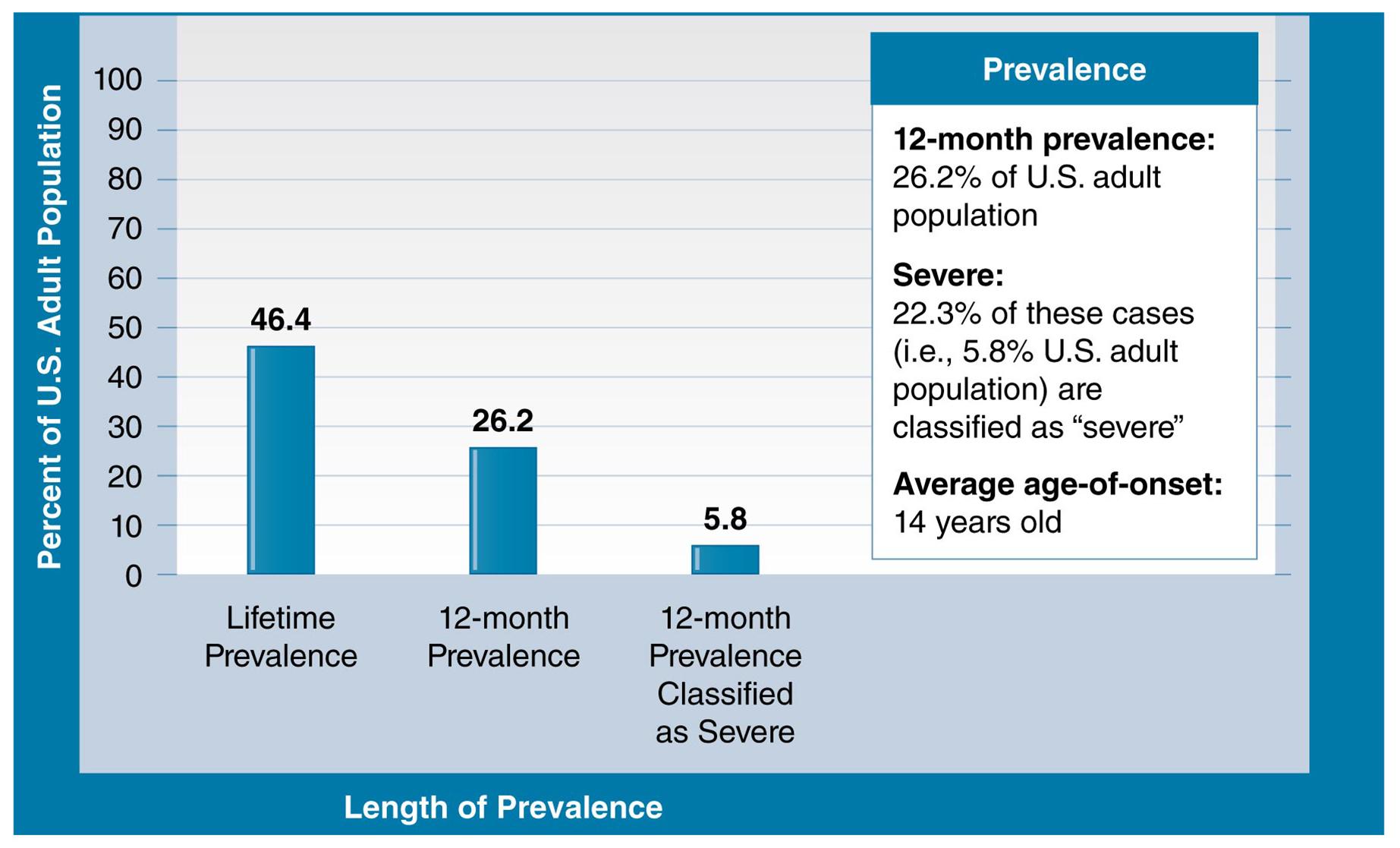

One noteworthy estimate is the 12-month prevalence of individuals who are affected by any DSM-IV (now DSM-5) disorder surveyed in the United States National Comorbidity Survey Replication (NCS-R) (Kessler, Chiu, Demler, & Walters, 2005). The NCS-R studied the prevalence of four categories of disorders: anxiety disorders, mood disorders, impulse-control disorders, and substance disorders. Persons with "any disorder" describes persons who had any one of the aforementioned DSM-IV disorders. The NCS-R found that more than one-quarter of the U.S. population had any disorder during a 12-month period; the 12-month prevalence of any DSM-IV disorder in the study was 26.2% of adults, as determined by a representative survey conducted between February 2001 and April 2003. See Figure 9.1.

Figure 9.1: Prevalence of any disorder among adults, United States, February 2001– April 2003

Source: NIMH. Statistics: Any disorder among adults. (n.d.i). Retrieved from http://www.nimh.nih.gov/statistics/1ANYDIS_ADULT.shtml

Mental disorders are common in the United States, and in a given year approximately one-quarter of adults are diagnosable for one or more disorders. However, only 5.8% of those are classified as "severe."

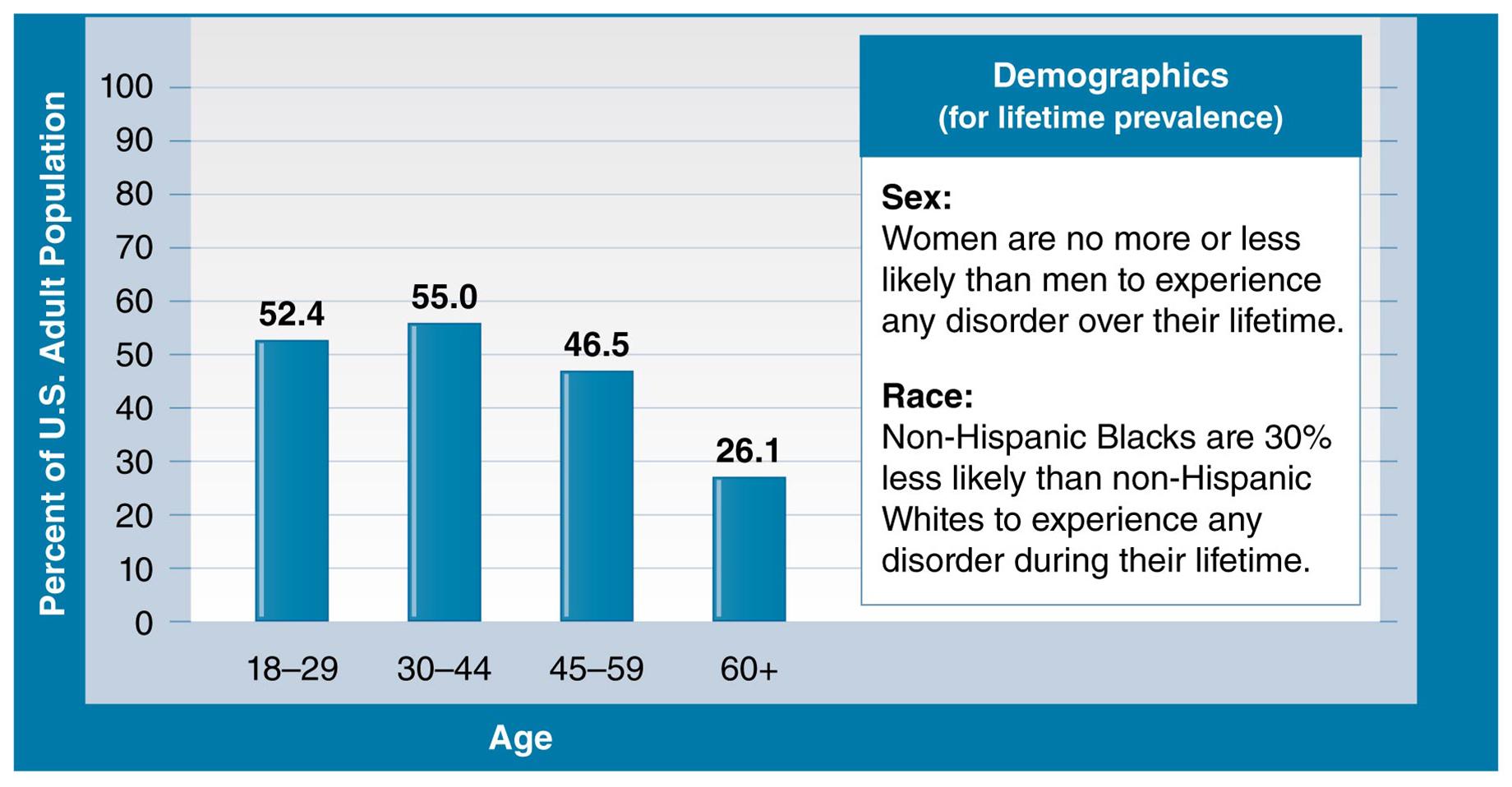

With respect to lifetime prevalence of any disorder, prevalence tends to be similar for men and women but differs among age groups (NIMH, n.d.l). The NCS-R (February 2001 through April 2003) found that among four age groups (18 to 29 years, 30 to 44 years, 45 to 59 years, and 60 years and older), the lifetime prevalence of any disorder was highest among persons aged 30 through 44 years—55.0%. See Figure 9.2. Based on data current as of 2007, the prevalence among this age group was 63.7 % (Harvard School of Medicine, n.d.).

Figure 9.2: Lifetime prevalence of any disorder by age group, United States, February 2001–April 2003

Source: NIMH. (n.d.i). Statistics: Any disorder among adults. Retrieved from http://www.nimh.nih.gov/statistics/1ANYDIS_ADULT.shtml

Lifetime prevalence of a disorder is highest for those in the 30–44 age group. Why might this group be more vulnerable than others?

Prevalence of Serious Mental Disorders

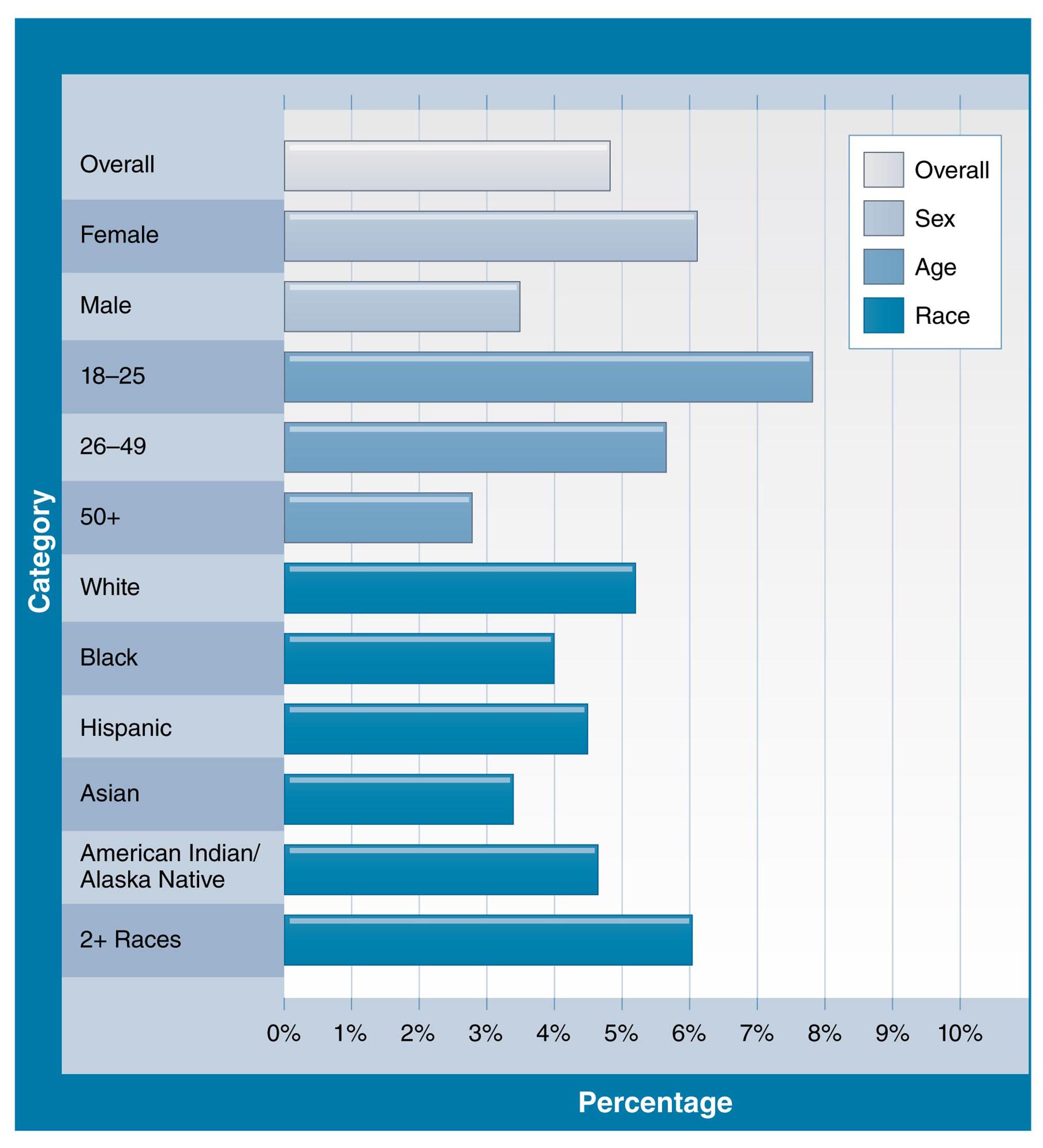

As indicated previously, the NCS-R reported a 12-month prevalence of 26.2% for any disorder. Of this total, about one-fifth of cases were classified by the researchers as serious; the 12-month prevalence of SMIs (according to the NCS-R data, 2001 through 2003) was about 5.8% among the adult population of the United States (NIMH, n.d.i). In 2008, according to data from the National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH), the prevalence of SMIs was higher among females than males (NIMH, n.d.l). Also, the prevalence of SMIs was highest among persons from two or more racial backgrounds in comparison with other racial/ethnic groups, and among persons aged 18 to 25 years in comparison with other age groups. See Figure 9.3.

Figure 9.3: Prevalence of serious mental illness among U.S. adults by sex, age, and race, 2008

Source: NIMH. (n.d.l). Statistics: Prevalence of serious mental illness among U.S. adults by age, sex, and race. Retrieved from http://www.nimh.nih.gov/statistics/SMI_AASR.shtml

Some demographics of Americans seem to be more vulnerable to mental illness than others. Or could certain groups, such as women, simply be more willing to come forward and discuss their symptoms than men?

Age and Variation Across the Life Span

Mental illnesses can affect persons of all ages: children and adolescents, adults, and older adults. The specific types of mental disorders tend to vary according to life stage (USDHHS, n.d.a). Some examples of these variations are provided in Spotlight: Mental Health Across Life Stages.

Spotlight: Mental Health Across Life Stages

Children and Adolescents

Approximately 20% of U.S. children and adolescents are affected by mental health disorders during their lifetime. Often, symptoms of anxiety disorders emerge by age 6, behavior disorders by age 11, mood disorders by age 13, and substance use disorders by age 15.

Up to 15% of high school students have seriously considered suicide, and 7% have attempted to take their own life.

Mental health disorders among children and adolescents can lead to school failure, alcohol or other drug abuse, family discord, violence, and suicide.

Adults

It is estimated that only about 17% of U.S. adults are considered to be in a state of optimal mental health. The remainder are either living with a mental health disorder in any given year or will have a mental health disorder over the course of their lifetime.

Almost 15% of women who recently gave birth reported symptoms of postpartum depression.

Older Adults

Alzheimer's disease is among the 10 leading causes of death in the United States. It is the sixth leading cause of death among American adults and the fifth leading cause of death for adults age 65 years and older.

Among nursing home residents, 18.7% of people age 65 to 74, and 23.5% of people age 85 and older have reported mental illness.

Source: Adapted from HealthyPeople.gov. Mental health. Retrieved from http://healthypeople.gov/2020/about/

Mental Health and Racial/Ethnic Disparities

The groundbreaking 2001 report from the Surgeon General on the influence of culture, race, and ethnicity on mental health concluded that racial and ethnic minorities in comparison with Whites have striking disparities with respect to access to mental health services. (USDHHS, 2001). An example of this is the disproportionate number of minority individuals in the homeless and prison populations with untreated mental health conditions. The report states that "racial and ethnic minorities bear a greater burden from unmet mental health needs and thus suffer greater loss to their overall health and productivity" (USDHHS, 2001, p. 3). Also, the report asserted that in comparison with Whites, racial and ethnic minorities:

have reduced access to mental health services,

are less likely to receive care,

are afforded lower-quality care,

do not benefit fully from advances in mental health treatment, and

have unmet needs for mental health services that are linked to reduced opportunities to contribute to society and lead a fulfilling lives.

9.3 Types of Mental Disorders

This section provides information about the disorders shown in Table 9.1. The discussion of anxiety disorders will cover five subtypes of anxiety disorders.

| Table 9.1: Examples of mental health disorders and conditions discussed in this section | |

| Anxiety disorders (five types) | Suicide |

| Bipolar disorder (manic-depressive disorder) | Eating disorders |

| Depression/major depression | Schizophrenia |

Anxiety Disorders

Anxiety disorders affect about 40 million American adults aged 18 years and older (about 18%) on an annual basis (NIMH, n.d.a). They include the following conditions:

Generalized anxiety disorder (GAD)

Obsessive–compulsive disorder (OCD)

Panic disorder

Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD)

Social phobia (also called social anxiety disorder).

Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD)

The NIMH characterizes persons with generalized anxiety disorder (GAD) as experiencing

excessive worry about a variety of everyday problems for at least six months. For example, people with GAD excessively worry about and anticipate problems with their finances, health, employment, and relationships. They typically have difficulty calming their concerns, even though they realize that their anxiety is more intense than the situation warrants. (NIMH, n.d.,a)

The National Comorbidity Survey reported that the 12-month prevalence of GAD was about 3%, according to data from 2007 (Harvard School of Medicine, n.d.). About one-third of GAD cases were serious (Kessler et al., 2005). Both the lifetime and 12-month prevalence were higher among women than men; for example, the 12-month prevalence was 3.4% among women and 1.9% among men, based on data available as of 2007. The 12-month prevalence of GAD was 2.0% among persons aged 18 to 29 years, increased to 3.5% among persons aged 30 to 44 years, remained about the same (3.4%) among persons aged 45 to 59 years, and then declined to 1.5% among persons aged 60 years and older.

Obsessive–Compulsive Disorder (OCD)

Garo/Phanie/SuperStock

Those who suffer from obsessive–compulsive disorder often fixate on certain ritualized actions, such as organizing everyday objects in specific ways for no apparent reason.

Classified as a type of anxiety disorder, obsessive–compulsive disorder (OCD) "is characterized by distressing repetitive thoughts, impulses or images that are intense, frightening, absurd, or unusual" (Farlex, Inc., n.d., para. 2). These thoughts are followed by ritualized actions that are usually bizarre and irrational. These ritual actions, known as compulsions, help reduce anxiety caused by the individual's obsessive thoughts. Often described as the "'disease of doubt,' the sufferer usually knows the obsessive thoughts and compulsions are irrational but, on another level, fears they may be true" (Farlex, Inc., n.d, para. 1.). Themes of obsessions can involve cleanliness, rechecking things, and counting; symptoms can be frequent hand washing that causes skin abrasions, organizing objects in the home in set patterns, and rechecking the stove after it has been shut off and the door after it has been locked. If these obsessions absorb too much of a person's time, ultimately they can be disabling (Mayo Clinic, 2010). The prevalence of OCD is similar for men and women and affects 2.2 million U.S. adults (NIMH, n.d.a).

Panic Disorder

One of the anxiety disorders, panic disorder, is

characterized by sudden attacks of terror, usually accompanied by a pounding heart, sweatiness, weakness, faintness, or dizziness. During these attacks, people with panic disorder may flush or feel chilled; their hands may tingle or feel numb; and they may experience nausea, chest pain, or smothering sensations. Panic attacks usually produce a sense of unreality, a fear of impending doom, or a fear of losing control. (NIMH, n.d.a, para. 9)

As estimated by data current as of 2007, the 12-month prevalence of panic disorder is 2.7% of the adult population, with women more frequently affected than men (3.8% versus 1.6%) (Harvard School of Medicine, n.d.). Onset of the disorder tends to occur during the age range of late adolescence to early adulthood.

Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD)

Symptoms of psychological distress among military personnel and veterans returning from theaters of battle led to popular awareness of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). The NIMH indicates that

post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is an anxiety disorder that can develop after exposure to a terrifying event or ordeal in which there was the potential for or actual occurrence of grave physical harm. Traumatic events that may trigger PTSD include violent personal assaults, natural or human-caused disasters, accidents, and military combat. People with PTSD have persistent frightening thoughts and memories of their ordeal, may experience sleep problems, feel detached or numb, or be easily startled. (NIMH, n.d.e)

© Neville Elder/Corbis Historical/Getty Images

Veterans are frequent victims of post-traumatic stress disorder as they struggle to reintegrate into society following combat.

Anyone who has experienced a traumatic event such as a vehicle crash, a natural disaster, or some other violent event can develop PTSD (NIMH, n.d.k). However, people differ in their vulnerability to PTSD, and not all those exposed to a traumatic situation will develop the condition. Following the occurrence of a disaster (for example, a bioterrorism event or a natural disaster such as an earthquake), affected individuals and clinicians can together develop coping strategies to deal with the mental health consequences of these tragic happenings (CDC, 2012). Clinicians should be aware of the special needs of persons who have experienced traumatic events. As an example of a method for helping victims cope with a traumatic event, clinicians could reassure traumatized persons that it is normal to have symptoms of distress following a disaster.

The 12-month prevalence of PTSD is slightly less than 4% of the adult population. The prevalence of PTSD among females is almost three times higher than among males (Harvard School of Medicine, n.d.). In comparison with adults, children have different PTSD symptoms, which can include the return of bedwetting and development of extreme attachment to a parent or other adult (NIMH, n.d.e).

Post-traumatic stress disorder can harm relationships with family and the community. Feelings of anger and depression, and not wanting to deal with people, can make it hard to connect with others. Family and community support for sufferers of PTSD is very significant. Meaningful relationships can make a big difference in recovery from PTSD.

Social Phobia (Social Anxiety Disorder)

Social phobia (also referred to as social anxiety disorder) is characterized by severe fear of being around people (NIMH, n.d.a). The NIMH states that social phobia

is diagnosed when people become overwhelmingly anxious and excessively self-conscious in everyday social situations. People with social phobia have an intense, persistent, and chronic fear of being watched and judged by others and of doing things that will embarrass them. They can worry for days or weeks before a dreaded [social] situation. This fear may become so severe that it interferes with work, school, and other ordinary activities, and can make it hard to make and keep friends. (NIMH, n.d.a, para. 39)

The NIMH estimates that about 15 million U.S. adults are affected by social phobias and that their occurrence is approximately equal in men and women. Onset occurs most often during childhood and the early teenage years.

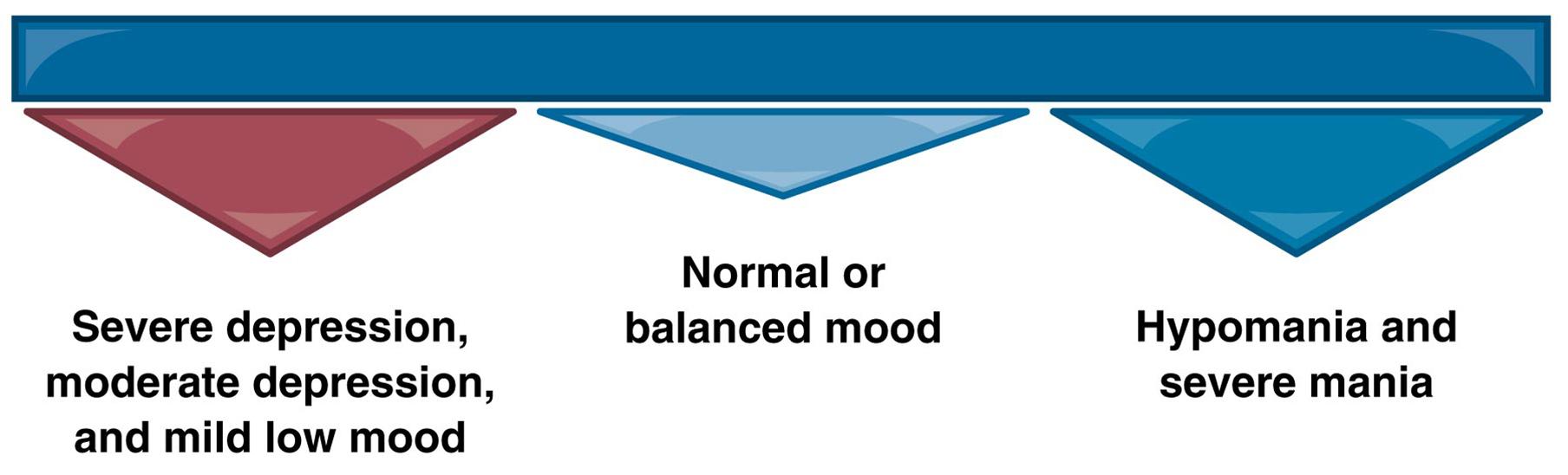

Bipolar Disorder

Bipolar disorder (also called manic-depressive disorder) has a 12-month prevalence of slightly less than 3% of the adult population. More than four-fifths of cases of bipolar disorder are serious (NIMH, n.d.b; Kessler et al., 2005). The lifetime prevalence (around 6%) is highest among persons between the ages of 18 and 29 years. Most often, the onset of bipolar disorder is before age 25, during the later teenage and early adult years. Figure 9.4 shows the pattern of moods associated with bipolar disorder. See Spotlight: Symptoms of Bipolar Disorder for information on the symptoms of bipolar disorder.

Figure 9.4: Range of moods associated with bipolar disorder

Source: United States Department of Health and Human Services. National Institutes of Health. Bipolar Disorder. NIH Publication No. 09-3679, Revised 2008, Reprinted 2009.

Those with bipolar disorder typically cycle through depressive episodes, periods where mood is normal, and periods of frenzy and mania—making for extreme highs and lows and great levels of unpredictability.

Spotlight: Symptoms of Bipolar Disorder

| Symptoms of mania or a manic episode include: | Symptoms of depression or a depressive episode include: |

| Mood Changes | Mood Changes |

|

|

| Behavioral Changes | Behavioral Changes |

|

|

| Source: United States Department of Health and Human Services. National Institutes of Health. Bipolar Disorder. NIH Publication No. 09-3679, Revised 2008, Reprinted 2009. | |

Description of Bipolar Disorder

Image Source/SuperStock

Those who suffer from bipolar disorder experience extreme bouts of emotion. A bipolar depressive episode goes beyond simply feeling down; it inhibits the ability to function normally.

Bipolar disorder, also known as manic-depressive illness, is a brain disorder that causes unusual shifts in mood, energy, activity levels, and the ability to carry out day-to-day tasks. Symptoms of bipolar disorder are severe. They are different from the normal ups and downs that everyone goes through from time to time. People with bipolar disorder experience unusually intense emotional states that occur in distinct periods called "mood episodes." An overly joyful or overexcited state is called a manic episode, and an extremely sad or hopeless state is called a depressive episode. Sometimes, a mood episode includes symptoms of both mania and depression. This is called a mixed state (USDHHS, 2009).

For the U.S. adult population, the 12-month prevalence of bipolar disorder is 2.6% of the adult population, with 2.2% of the population classified as severe (Kessler et al., 2005). However, health care utilization is sorely lacking for this population with the disorder. For example, while 48.8% of those diagnosed are receiving treatment, only 18.8% of them are receiving minimally adequate care (Wang et al., 2005).

Source: Reprinted from United States Department of Health and Human Services. (2009). National Institutes of Health. NIH Publication No. 09-3679, p. 1. Revised 2008, Reprinted 2009.

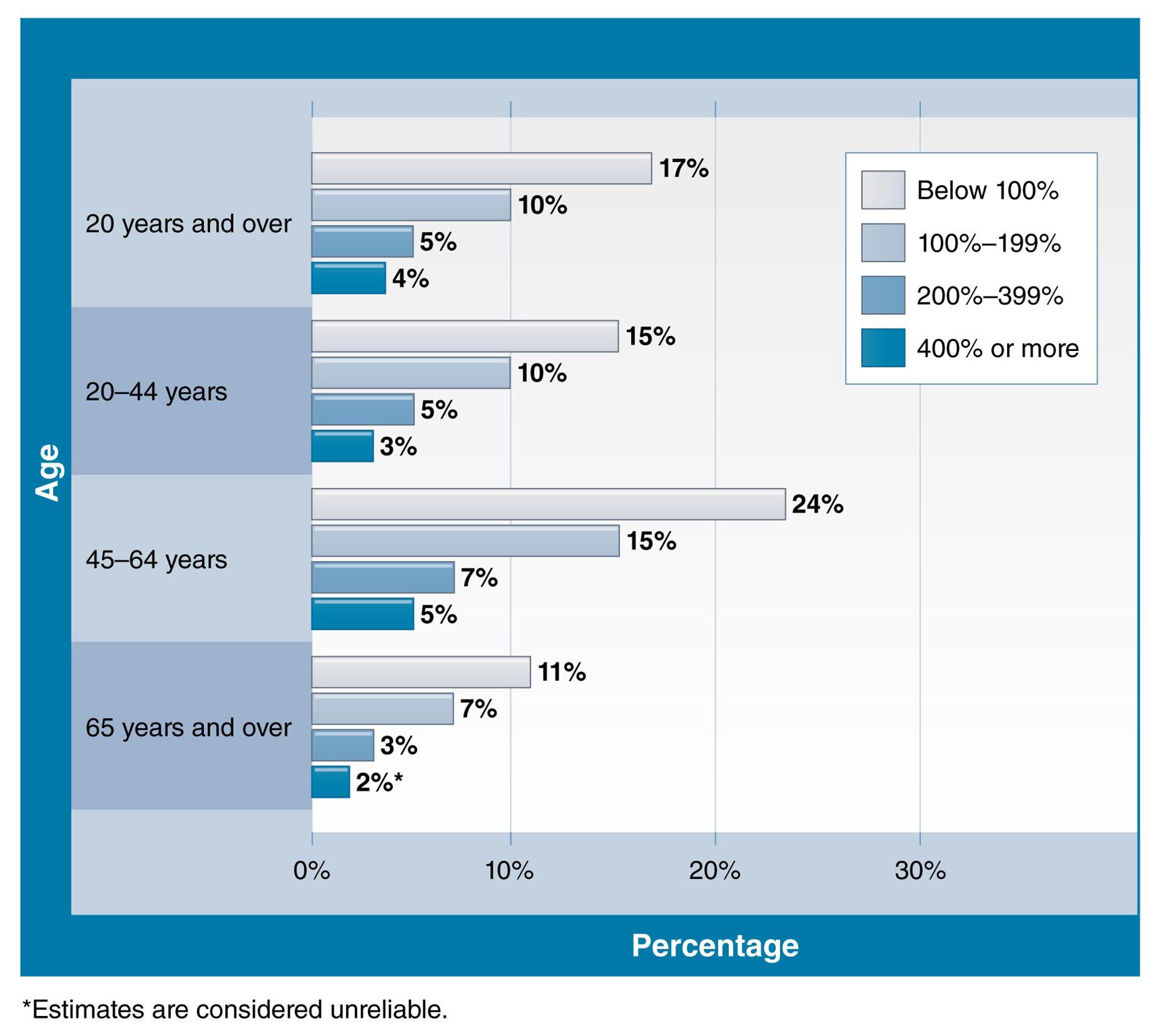

Depression

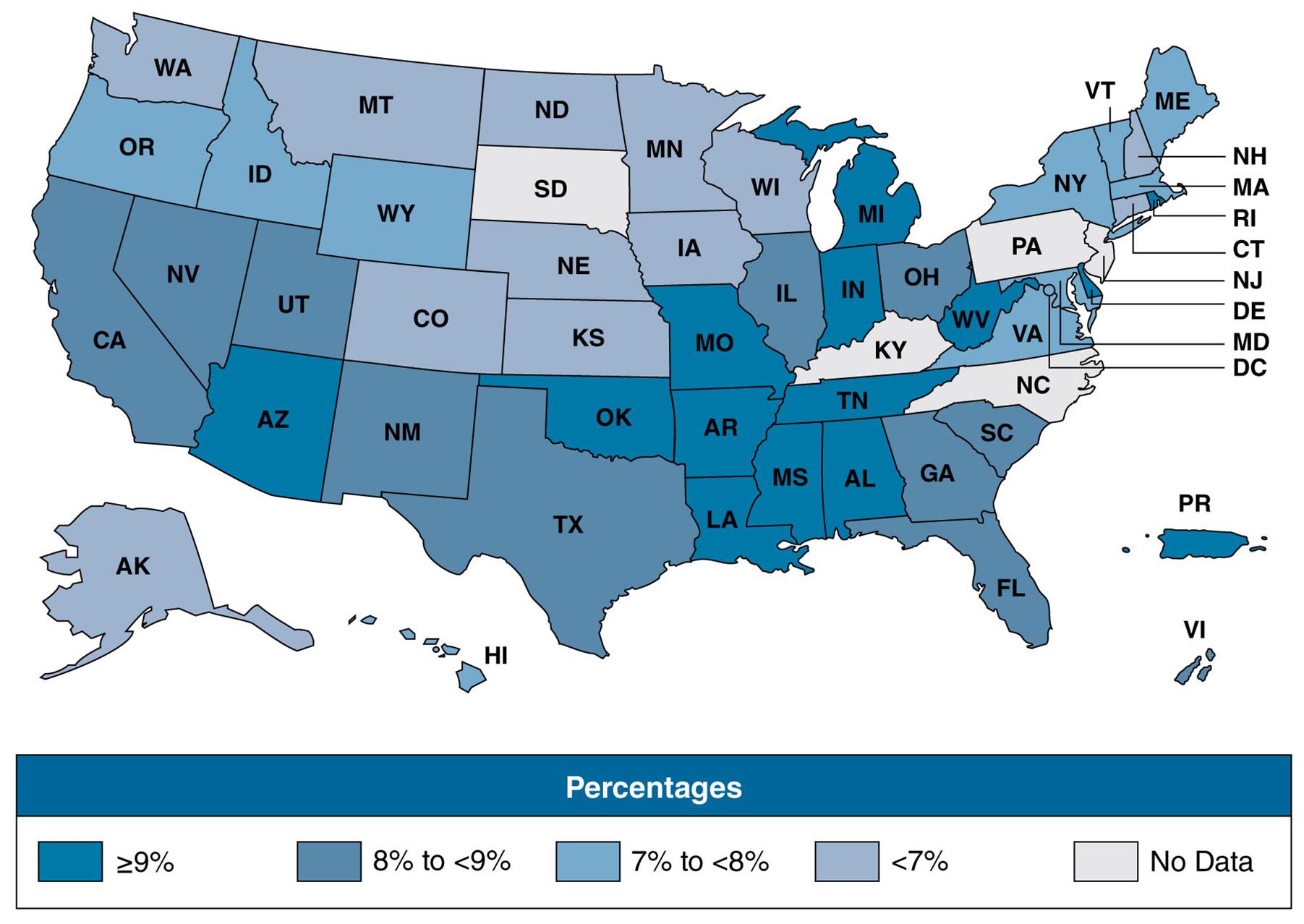

Depression is characterized by a "depressed or sad mood, diminished interest in activities, which used to be pleasurable, weight gain or loss, psychomotor agitation or retardation, fatigue, inappropriate guilt, difficulties concentrating, as well as recurrent thoughts of death" (CDC, 2011b, para. 1). Also called a mood disorder, depression is among the most frequently occurring forms of mental illness in the United States (CDC, 2011d). Depression has the highest concentration in the southeastern states (CDC, 2011c, 2011a). (Refer to Figure 9.5.) The prevalence of depression is highest among persons who are below the poverty level (CDC, 2011g). (Refer to Figure 9.6.) Table 9.2 provides data on the epidemiologic characteristics of depression in the United States. The National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES), 2005–2008, found that a total of 6.8% of adults had current depression (i.e., depression that had occurred during the previous 2 weeks before they were interviewed). The prevalence of depression was almost twice as high among females as among males.

Figure 9.5: Prevalence of current depression among adults aged 18 years and older, by state quartile—Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System, United States, 2006

Source: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2011). Mental illness surveillance among adults in the United States. MMWR, 60(Suppl), 13.

Rates of depression can vary by geographical region. What factors might account for such variance?

Figure 9.6: Depression among adults 20 years of age and older, by age and percent of poverty level, United States, 2005–2010

Source: National Center for Health Statistics. (2012). Health, United States, 2011: With special feature on socioeconomic status and health. Hyattsville, MD. 2012.

For each age group, depression rates rise with increased poverty levels.

| Table 9.2: Prevalence of depression among adults aged 18 years and older, by sociodemographic characteristics—National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, United States, 2005—2008 | |||

| Characteristic | Number | Percent | (95% CI) |

| Total | 10,279 | 6.8 | (5.8–7.8) |

| Sex |

|

|

|

| Male | 6,240 | 4.9 | (3.9–5.9) |

| Female | 6,397 | 8.4 | (7.4–9.4) |

| Age group (years) |

|

|

|

| 18–39 | 4,093 | 6.2 | (5.2–7.2) |

| 40–59 | 2,992 | 8.4 | (6.8–10.0) |

| ≥60 | 3,194 | 5.2 | (4.0–6.4) |

| Race/Ethnicity |

|

|

|

| Mexican American | 1,983 | 7.2 | (5.6–8.8) |

| Black, non-Hispanic | 2,273 | 9.7 | (7.9–11.5) |

| White, non-Hispanic | 4,882 | 6.2 | (5.0–7.4) |

| Abbreviation: CI = confidence interval, which is statistical range with a specified probability that a given parameter lies within the range. | |||

| Source: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2011). Mental illness surveillance among adults in the United States. MMWR, 60(suppl), 23. | |||

In addition to depressed mood, sleep disturbance is another common symptom of depression. The condition is also associated with risk behaviors that include smoking, drinking, and physical inactivity. When depressed individuals do not receive treatment, they can lapse into a chronically depressed state. Also, previous episodes of depression increase the risk of future episodes.

As noted, depression can result in impaired interpersonal relationships and dysfunctional behavior. Thus, it is a difficult mental health issue for the family members who live with the depressed person. Severe depression is a risk factor for suicide. As a result, friends and family members need to be aware of the risk of suicide when a person is severely depressed. Sometimes depression is a comorbid feature of chronic diseases and may be a risk factor for their occurrence as well as a component of their natural history (Chapman, Perry, & Strine, 2005). In addition, people who have serious chronic diseases may become depressed as a result of their afflictions.

A severe form of depression is known as major depressive disorder, which is "a severely depressed mood and activity level that persists two weeks or more. [A person with major depressions has] symptoms [that] interfere with their daily function, and cause distress for both the person with the disorder and those who care about him or her" (NIMH, n.d.j., para. 1). A very common disorder in the United States, major depression (based on data as of 2007) has a lifetime prevalence of 16.9% (Harvard School of Medicine, n.d.). The lifetime prevalence of major depression among adult females is 20.2% in comparison with 13.2% among adult males.

Suicide

As an introduction to the topic of suicide, refer to Spotlight: Key Facts About Suicide.

Spotlight: Key Facts About Suicide

Burger/Phanie/SuperStock

Clinics such as this medico-psychiatric unit in France specialize in treating or monitoring young adults suffering from mental illness.

Suicide claims more than twice as many lives each year as homicide does.

On average, between 2001 and 2009, more than 33,000 Americans died each year as a result of suicide, which is more than 1 person every 15 minutes.

More than 8 million adults report having serious thoughts of suicide in the past year, 2.5 million [persons] report making a suicide plan in the past year, and 1.1 million report a suicide attempt in the past year.

Almost 16 percent of students in grades 9 to 12 report having seriously considered suicide, and 7.8 percent report having attempted suicide one or more times in the past 12 months.

Source: Adapted from United States Department of Health and Human Services. (2012, September). Office of the Surgeon General and National Action Alliance for Suicide Prevention. 2012 National Strategy for Suicide Prevention: Goals and objectives for action. Washington, DC: USHHS.

The Office of the Surgeon General and the National Alliance for Suicide Prevention state that "suicide is a serious public health problem that causes immeasurable pain, suffering, and a loss to individuals, families, and communities nationwide" (USDHHS, 2012, p. 10). Even though suicide is the 10th leading cause of death in the United States, these deaths, according to the Office of the Surgeon General, represent the "tip of the iceberg" because suicide attempts are 30 times more frequent than deaths from suicide.

Among teenagers, there is a strong link between bullying and suicide. In recent years, this link has been illustrated by the number of prominently covered cases of bullying-related suicides in the United States (and across the globe). This suggests that community-based programs to prevent bullying, where effective, may help to lower the risk of teen suicide.

The Terminology of Suicide

A suicide is a "death caused by self-directed injurious behavior with any intent to die as a result of the behavior" (USDHHS, 2012, p. 14). The term "intentional self-harm" is used in mortality statistics as a synonym for suicide. Table 9.3 gives definitions of terms related to suicide.

| Table 9.3: Terms related to suicide and their definitions | |

| Term | Definition |

| Affected by suicide | All those who may feel the effect of suicidal behaviors, including those bereaved by suicide, community members, and others. |

| Behavioral health | A state of mental and emotional being and/or choices and actions that affect wellness. Behavioral health problems include mental [disorders] and substance use disorders and suicide. |

| Bereaved by suicide | Family members, friends, and others affected by the suicide of a loved one (also referred to as survivors of suicide loss). |

| Means | The instrument or object used to carry out a self-destructive act (e.g., chemicals, medications, illicit drugs). |

| Methods | Actions or techniques that result in an individual inflicting self-directed injurious behavior (e.g., overdose). |

| Suicidal behaviors | Behaviors related to suicide, including preparatory acts, suicide attempts, and deaths. |

| Suicidal ideation | Thoughts of engaging in suicide-related behavior. |

| Suicide | Death caused by self-directed injurious behavior with any intent to die as a result of the behavior. |

| Suicide attempt | A nonfatal, self-directed, potentially injurious behavior with any intent to die as a result of the behavior. A suicide attempt may or may not result in injury. |

| Source: Data from United States Department of Health and Human Services (2012, September). Office of the Surgeon General and National Action Alliance for Suicide Prevention. 2012 National Strategy for Suicide Prevention: Goals and objectives for action (p. 14). Washington, DC: USDHHS. | |

Epidemiology of Suicide

In 2009, intentional self-harm (suicide) was the 10th leading cause of death in the United States and was associated with 36,909 deaths—a total of 1.5% of all deaths (CDC, 2013; NIMH, n.d.h). Geographic data for 2000 to 2006 indicate that counties in the western United States, Appalachian counties in Kentucky and West Virginia, and counties in southern Oklahoma and northern Florida had higher suicide rates than other areas of the United States.

There is no unanimous agreement on the factors that can account for regional differences in suicide rates. Regional differences in demographic patterns might account for part of the variance. Such factors might include regional differences in factors such as the level of firearm ownership and availability, the education levels of the populations, the percentage of the population that is married, and the unemployment levels of the population. However, none of these variables alone account for the differences in suicide rates, as it is more likely that there is a whole spectrum of social and environmental factors that contribute to suicide rates.

Several states in the West have initiated multipronged strategies for suicide prevention. For example, in Washington, the suicide prevention plan includes "multiple interventions such as improving suicide surveillance efforts, public education campaigns, crisis intervention services, and family support programs" (CDC, 1997). See Spotlight: Risk Factors of Suicide for additional risk factors researchers have identified for suicide.

Spotlight: Risk Factors of Suicide

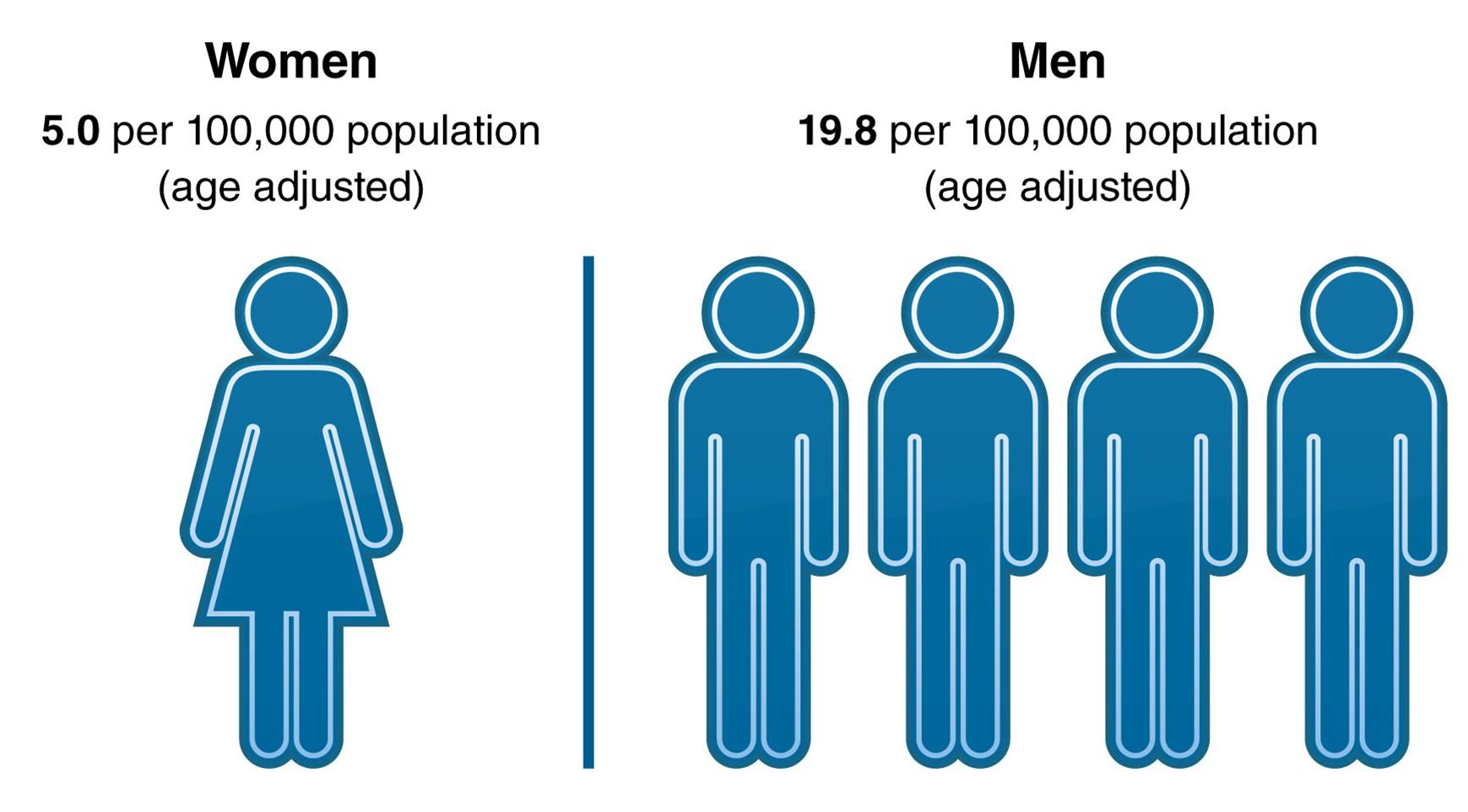

Gender Differences

Suicide, which is consistently more frequent among males than females, was the seventh leading cause of death among males in 2009 but was not among the 10 leading causes of death for females. In 2011, the suicide rate among males was about four times higher than the rate among females. Refer to Figure 9.7.

Figure 9.7: Suicide rate by sex, 2011

Source: HealthyPeople.gov. Mental health. Available at http://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/LHI/mentalHealth.aspx?tab=data

The suicide rate is four times higher among men than women. What contributing factors might make men more susceptible to suicide than women?

Time Trends

From 1991 to 2000, the suicide rate declined slightly for both males and females who were 10 years of age and older (CDC, 2013b). Since 2000, suicide rates have increased gradually among both sexes.

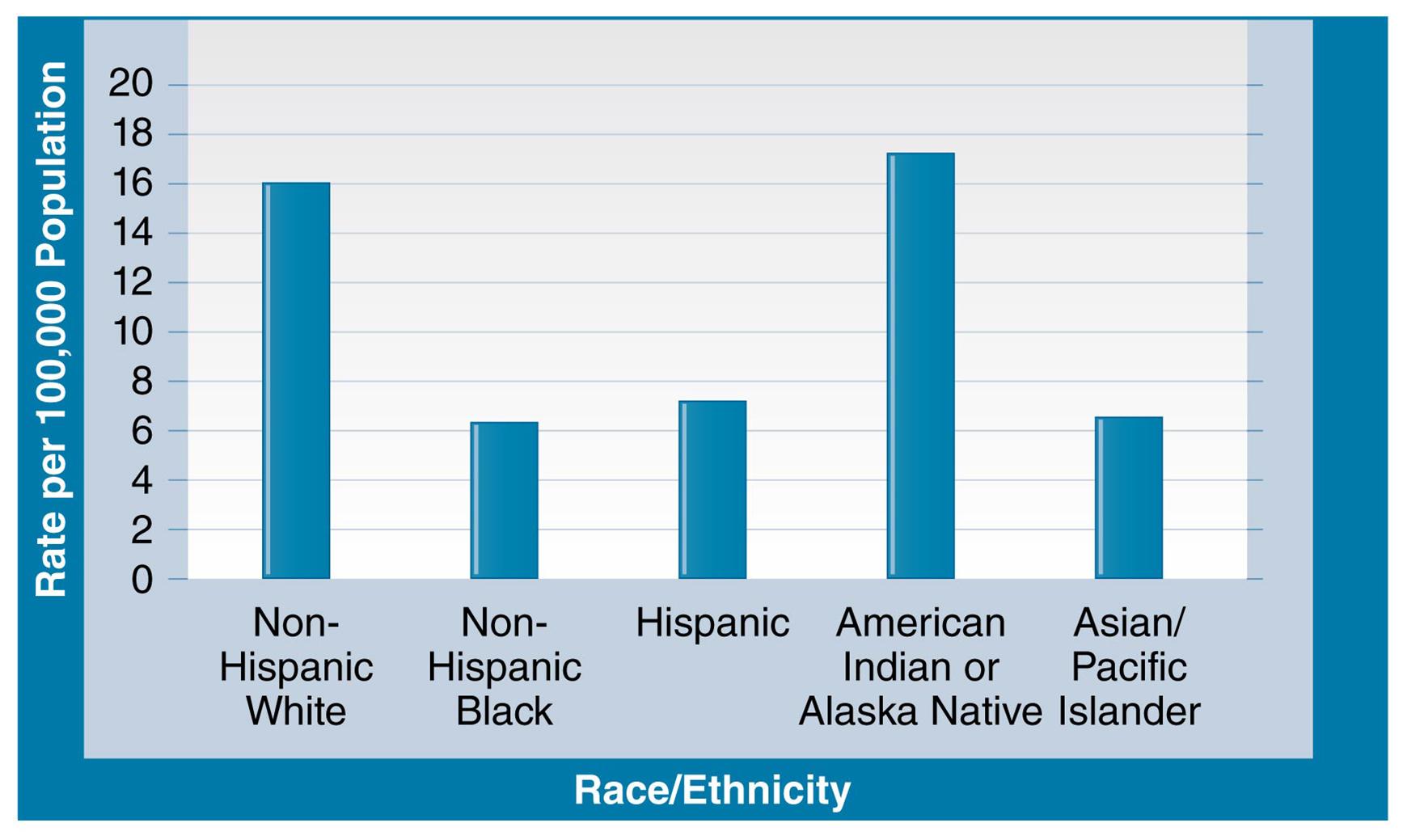

Racial and Ethnic Differences

Suicide rates vary according to race and ethnicity. The CDC reported that during the period of 2005 through 2009, American Indians/Alaska Natives had the highest suicide rates of five racial/ethnic groups (17.48 suicides per 100,000) (2013c). The second highest rate was among non-Hispanic Whites (15.99 suicides per 100,000). Refer to Figure 9.8 for more information.

Figure 9.8: Racial/ethnic variations in suicide

Source: CDC. (2013c). Suicide rates by race ethnicity. Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/ViolencePrevention/suicide/statistics/rates01.html

Suicide rates vary by race and ethnicity. Non-Hispanic Blacks, Asians/Pacific Islanders, and Hispanics have the lowest rates, at around 6–7 suicides for every 100,000 people. What might account for higher rates of suicide among Non-Hispanic White and American Indian/Alaskan Native groups?

Mechanisms of Suicide

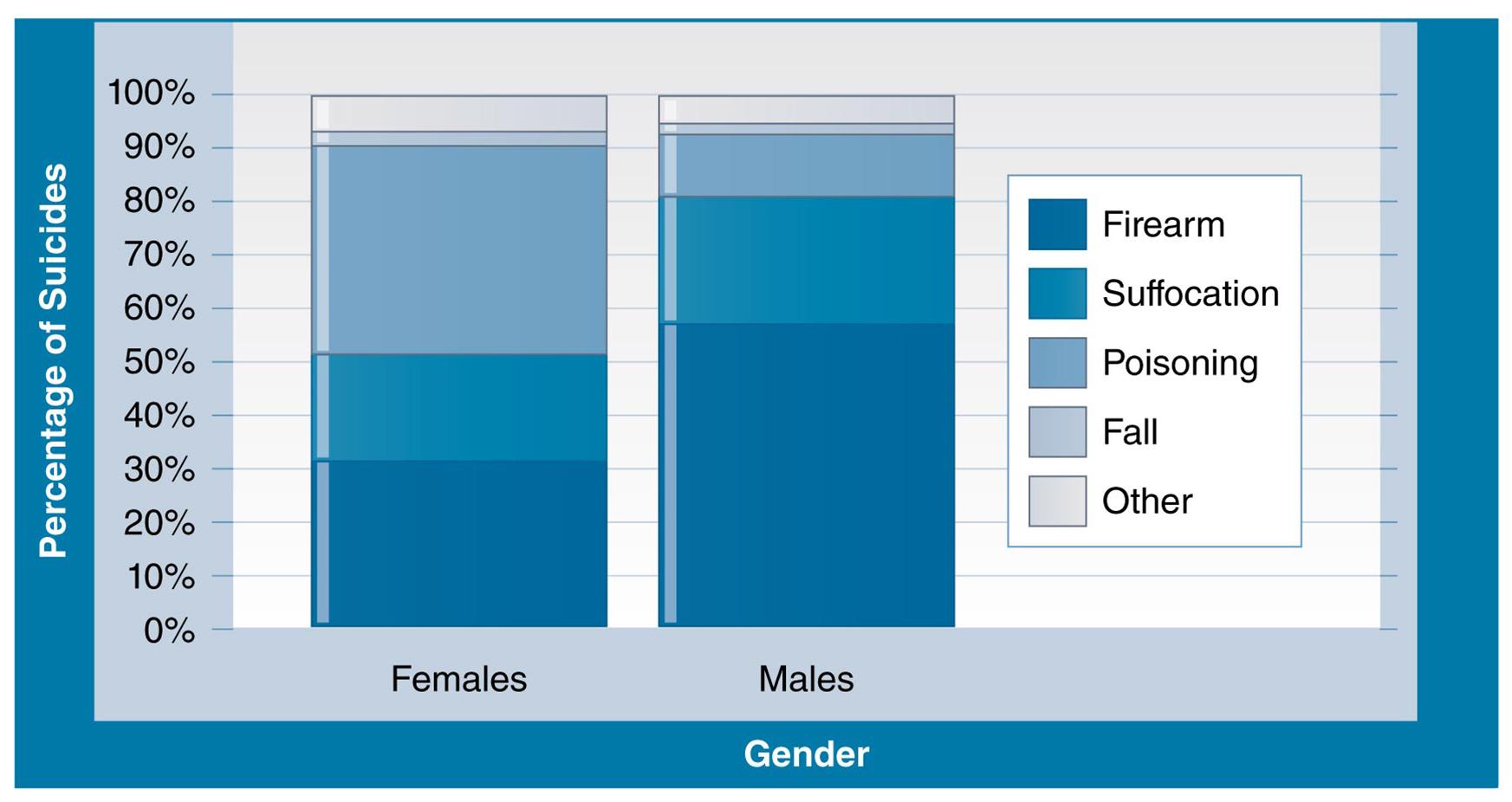

Common means and methods (mechanisms) for committing suicide are firearm use, falls, suffocation, and poisoning. Almost two-thirds of suicides in the United States among males involved the use of firearms (2005–2009 data), which was the most frequent method (CDC, 2013d). Among females, the most frequent method was poisoning, which accounted for about four-fifths of female suicides. Figure 9.9 presents information on mechanisms of suicide.

Figure 9.9: Percentage of suicides among persons ages 10 years and older, by sex and mechanism, United States, 2005–2009

Source: CDC. (2013d). Suicide rates by sex and mechanism. Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/ViolencePrevention/suicide/statistics/mechanism01.html

Methods of suicide vary by gender. Men are almost twice as likely to commit suicide with a firearm than women are.

Eating Disorders

Eating disorders present serious health issues that can cause significant morbidity and can be life threatening. Consequently, it is imperative for persons with these conditions to receive treatment. Although the prevalence of eating disorders is uncertain, studies show that they usually have onset during the teenage years (NIMH, n.d.c). Eating disorders affect both genders, but females have a higher probability than males of developing an eating disorder (USDHHS, 2010). One possible influence that contributes to eating disorders is the desire of young women to emulate female models and actresses who are slim. Other possible factors related to eating disorders are responses to feelings of helplessness, experiences of life stresses, biological influences, and co-occurrence of mental disorders such as anxiety and depression. Three examples of eating disorders are anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa, and binge-eating disorder. The definitions of these conditions are as follows:

Anorexia nervosa is a condition described as "extreme thinness (emaciation), . . . [d]istorted body image, . . . [and] extremely restricted eating" (NIMH, n.d.c, p. 2). Persons who have this disorder are very thin.

Bulimia nervosa is a disorder characterized by

recurrent and frequent episodes of eating unusually large amounts of food and feeling lack of control over these episodes. This binge-eating is followed by behavior that compensates for the overeating such as forced vomiting, excessive use of laxatives or diuretics, fasting, excessive exercise, or a combination of these behaviors (NIMH, n.d.c, p.3).

Persons with bulimia nervosa typically have normal weight or are slightly overweight.

Binge-eating disorder is described as a state in which "a person loses control over his or her eating. Unlike bulimia nervosa, periods of binge-eating are not followed by purging, excessive exercise, or fasting" (NIMH, n.d.c, p. 4). Persons with this condition are frequently overweight.

Eating disorders and their complications account for a significant portion of public and community health services consumed. Some estimates indicate that as many as 8 million Americans suffer from some kind of eating disorder, including 7 million women and 1 million men. In addition, the mortality rate due to mental illness is higher for eating disorders than for any other type of mental disorder. According to a study conducted by the National Association of Anorexia Nervosa and Associated Disorders,

5–10% of anorexics die within 10 years after contracting the disease;

18–20% of anorexics will be dead after 20 years and only 30–40% ever fully recover.

The mortality rate associated with anorexia nervosa is 12 times higher than the death rate of all other causes of death for females 15–24 years old.

20% of people suffering from anorexia will prematurely die from complications related to their eating disorder, including suicide and heart problems. (http://www.state.sc.us/dmh/anorexia/statistics.htm, para. 2).

Schizophrenia

The NIMH defines schizophrenia as "a chronic, severe, and disabling mental disorder characterized by deficits in thought processes, perceptions, and emotional responsiveness" (n.d.f, para. 1). Schizophrenia is a complex mental disorder with the potential for severe negative consequences for the affected person and family members. Persons with schizophrenia are at risk for other adverse conditions such as suicide. Fortunately, treatments involving the use of medications and rehabilitation can be effective for individuals who have this disorder. Three types of symptoms characterize schizophrenia: positive, negative, and cognitive (NAMI, n.d.a). Some examples of these symptoms are as follows:

Positive (out of touch with reality):

? Hallucinations (e.g., hearing voices)

? Delusions (e.g., thinking that one is a famous person)

? Thought disorders (e.g., thinking illogically)

? Movement disorders (e.g., making repetitive motions)

Negative (loss of normal emotions and behaviors):

? Flat affect, which means reduced or no emotional responsiveness

? Inability to complete tasks

? Loss of the capacity to enjoy life

Cognitive

? Difficulty in focusing on activities

? Reduced decision-making ability

? Reduced "working memory," which involves use of information soon after it is learned.

Yuri Arcurs Media/SuperStock

Schizophrenic hallucinations can begin to manifest starting in early adulthood.

The 12-month prevalence of schizophrenia is slightly more than 1% (2.4 million Americans over age 18), with variations in prevalence by sex, race, and age not determined (NIMH, n.d.m). The age of onset for both males and females is during early adulthood—from the late teenage years to early adult years among males, and from the late 20s to early 30s among females (NAMI, 2013). The etiology of schizophrenia suggests an interaction between inherited factors and environmental influences (NAMI, n.d.c). Studies of identical twins show that if one twin has schizophrenia, the other twin has an increased (50%) likelihood of being affected. The role of family environment in the development of schizophrenia is not clear-cut. Children who have a biological parent with schizophrenia but live in adoptive families are more likely to develop schizophrenia than children in general—a finding that tends to support an inherited rather than an environmental basis for schizophrenia.

9.4 Etiology of Mental Disorders

The etiology of mental disorders in most cases has not been delineated clearly (USDHHS, 1999). Most likely, mental disorders stem from a combination of human biological and psychological influences that are impacted by environmental influences—for example, from the physical environment, society, and culture. Mental illness is hypothesized to result from an interaction among inherited characteristics, in utero environmental influences, adverse life events, and chemicals in the brain (Mayo Clinic, 2012). Also, chronic diseases and mental disorders frequently co-occur (CDC, 2011f). Refer to Spotlight: Overview of Etiology of Mental Disorders for a statement on the causes of mental illness from the Surgeon General.

Spotlight: Overview of Etiology of Mental Disorders

The precise causes (etiology) of most mental disorders are not known. But the key word in this statement is precise. The precise causes of most mental disorders—or, indeed, of mental health—may not be known, but the broad forces that shape them are known; these are biological, psychological, and social/cultural factors. What is most important to reiterate is that the causes of health and disease are generally viewed as the product of the interplay or interaction between [sic] biological, psychological, and sociocultural factors. This is true for all health and illness, including mental health and mental illness. For instance, diabetes and schizophrenia alike are viewed as a result of interactions between [sic] biological, psychological, and sociocultural influences. With these disorders, a biological predisposition is necessary but not sufficient to explain their occurrence. . . . For other disorders, a psychological or sociocultural cause may be necessary, but again not sufficient.

Source: Reprinted from United States Department of Health and Human Services. (1999). Mental health: A report of the Surgeon General, p. 49. Rockville, MD: USDHHS, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Center for Mental Health Services, National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Mental Health.

Inherited/Genetic Predisposition

Some mental disorders (for example, bipolar disorder and schizophrenia), appear to have an inherited basis. Consequently, family history is a potential indicator for the occurrence of these two disorders. The NIMH reports that "if you have a close relative with bipolar disorder, you have about a 10 percent chance of getting a mood disorder, such as bipolar disorder or depression" (n.d.d, para. 36). However, at present, no genetic test is available for predicting whether a person will develop a mental disorder. Geneticists do not know which genes or combinations thereof are linked to mental illness or to what extent other factors contribute. "The concept of the causative gene has been replaced by that of genetic complexity, in which multiple genes act in concert with non-genetic factors to produce a risk of mental disorder" (Hyman, 2000, p. 455).

Environmental Toxins and Mental Disorders

Photograph of a sign warning of mercury-containing fish.

Universal Images Group/SuperStock

A sign posted near a Wisconsin lake warns of mercury-containing fish.

The role of exposures to environmental toxins in the etiology of mental disorders is an extremely complex issue. With respect to physical health, a number of toxic chemicals and substances are associated with adverse physical outcomes. However, in comparison with research on physical health effects of exposure to toxins, the relationships between environmental exposures and mental health outcomes are not as well understood (Collaborative on Health and the Environment, n.d.).

Some toxic heavy metals (e.g., lead and mercury), can affect the human nervous system. Exposure to lead has the potential to affect every organ and system of the human body including the brain and nervous system. Lead exposure, particularly during childhood, can cause permanent brain damage and is related to children's behavior problems. Another potentially dangerous heavy metal is mercury, which can impede development of the human nervous system and impair cognitive skills among exposed fetuses, infants, and children.

Toxic chemicals, pesticides, and infectious disease agents can disturb the human brain. Examples of toxic environmental chemicals that may produce neurological effects are some types of industrial chemicals, which are called selective neurotoxic agents and are capable of disrupting the neurological system and causing behavioral disturbances. Acute exposures to some types of pesticides can impact the human nervous system and produce short-lived mental illness symptoms such as depression. Finally, infections caused by some viruses, parasitic agents, and bacteria can damage the human brain and increase the potential for mental disorders.

Stress and Mental Disorders

The Oxford College Dictionary defines stress as "a state of mental or emotional strain or tension resulting from adverse or very demanding circumstances" (para. 2). Stress can arise from a variety of sources including the structure and organization of communities, sociocultural factors, and difficult interpersonal relationships. In recent decades, societal and economic changes have exacerbated people's sense of stress. These changes have included economic retrenchment in the United States and abroad, reduced employment opportunities in some fields, and fundamental changes in the structure and nature of work. Many people in the community are under stress because they are unable to afford basic necessities such as housing and health care. Some researchers posit that the consequences of these societal and economic stresses are increases in suicide rates, levels of psychological depression, family dysfunction, interpersonal violence, and criminality.

Photograph of a mother stressed over financial issues.

© Jim Craigmyle/Getty Images

Stress seems not only able to contribute to minor pains, like headaches, but also to more long-term illnesses.

According to stress theorists, stress is hypothesized to increase the risk of a wide range of physical and mental health outcomes including mental disorders—although stress research is complex as well as controversial. One possible impact of stress might be the induction of physiological changes such as alterations to the immune system, thereby increasing vulnerability to microorganisms and other disease agents. When human beings experience stress, various bodily systems can become unbalanced, lowering one's resistance to adverse environmental influences. The theory of homeostasis argues that bodily mechanisms known as homeostatic regulatory mechanisms help one to maintain balance among essential biological functions. The definition of homeostasis is the tendency for maintenance of stable equilibrium among physiological processes when they become disrupted.

One category of stress sources is stressful life events—for example, death of a spouse, death of a close family member, or serious injury. Researchers hypothesize that the experience of adverse stressful life events can increase the risk of some types of mental disorders such as depression. The availability of social support, defined as supportive interpersonal relationships arising from families and friends, is thought to be instrumental in helping individuals cope with stressful life events and other types of stress.

9.5 Treatments for Mental Disorders

One of the principal treatments for mental disorders, particularly severe and disabling mental illnesses, is the use of psychotherapeutic medications. Other modalities include psychotherapy (either on an individual basis from a clinician or in a group setting), behavioral therapy, and cognitive–behavior therapy. Behavioral therapy attempts to encourage desirable behaviors through reward and reinforcements—for example, rewarding a messy child for cleaning up his or her room. Cognitive–behavior therapy helps persons with mental disorders to develop insights into thought processes that affect their behavior in adverse ways. For situations in which other forms of treatment are not successful, brain stimulation has been used for treatment of depression as well as several other types of mental disorders. An example of brain stimulation is electroconvulsive therapy (ECT), which is stimulation of the brain with an intense electric current.

Conceptual artwork of pills with a brain symbol embossed on them.

Science Photo Library/SuperStock

Prescription medications are the most popular treatment for mental illness.

According to estimates from the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA), a total of 13.4% of U.S. adults were receiving treatment for mental health problems in 2008. This total included medicines prescribed for mental health problems (the most common form of treatment), outpatient care, and inpatient care (NIMH, n.d.n). Almost three-fourths of adults with major depression were receiving some form of mental health services.

Role of Medications

Several categories of psychiatric medications are available for treatment of mental disorders (NIMH, n.d.a). These medicines can relieve symptoms and help to improve or restore functioning to persons who have mental disorders. Although medications can aid persons with mental illnesses to lead productive lives, they do not cure mental disorders. Also, their use should not be discontinued without the advice of a health care professional. Some individuals with disorders such as some types of depression may need only to take a medication for a short time and can discontinue when the symptoms have diminished. Persons who have serious disorders such as schizophrenia may need to continue taking their medications indefinitely, or else symptoms and behavioral dysfunctions will reappear. Some of the available psychiatric medications can produce unpleasant side effects that cause people to stop taking them. Examples of types of medications are:

Antidepressants—for the treatment of depression and sometimes for anxiety disorders

Mood-stabilizing medications—for treatment of bipolar disorder

Anti-anxiety drugs—for treatment of anxiety disorders such as generalized anxiety disorder. Beta-blockers (used for treatment of high blood pressure) are used also for some anxiety disorders.

Antipsychotic drugs (neuroleptics)—for treatment of schizophrenia and other psychotic disorders.

Photograph of an abandoned mental hospital.

iStockphoto/Thinkstock

Numerous mental hospitals were closed down with the deinstitutionalization of the severely mentally ill. This often left patients with nowhere to go for treatment.

Deinstitutionalization of the Severely Mentally Ill

During the 1950s, the policy of deinstitutionalization of the severely mentally ill began to take effect (PBS, 2005; SAMHSA, 2005). This policy involved removing people who had severe mental illnesses from state mental hospitals and then closing down these facilities or parts of them. Deinstitutionalization followed the availability of effective antipsychotic medications such as Thorazine and was further reinforced by a later impetus from Medicaid and Medicare. From 1955 to 1994, the number of patients hospitalized in psychiatric institutions dropped precipitously from about 558,000 to about 72,000.

In many communities, deinstitutionalization of the severely mentally ill has transpired without having sufficient treatment and rehabilitation services in place. As a result, a large number of severely mentally ill persons who require treatment are not receiving needed services. One of the consequences of deinstitutionalization has been an increase in the number of severely mentally ill persons in jail (NIMH, n.d.g). In addition, beginning in the 1980s when housing began to be much less affordable for those living on the margins, the deinstitutionalized mentally ill began to become homeless on a much larger scale than ever before.

Behavioral Health Services and Community Mental Health Care

Behavioral health care pertains to the provision of services for mental disorders, behavioral disorders, and substance abuse. Ideally these services should be coordinated as part of a comprehensive approach to mental health care.

An innovative method for providing behavioral health care is via community mental health care.

Community mental health care comprises the principles and practices needed to promote mental health for a local population by: 1) addressing population-based needs in ways that are accessible and acceptable; 2) building on the goals and strengths of people who experience mental illnesses; 3) promoting a wide network of supports, services, and resources of adequate capacity; and 4) emphasizing services that are both evidence-based and recovery-oriented. (Thornicroft, Szmukler, Mueser, & Drake, 2011, p. 4)

Table 9.4: The balance of community mental health services

Keys to developing balanced community mental health services Key challenges for those providing services Three core principles to serve as a guide

• Services should reflect the priorities of both service users and caregivers.

• Both hospital and community services are needed.

• Services should be offered close to home.

• Some services need to be mobile rather than static.

• Interventions need to address both symptoms and disabilities.

• Treatment has to be specific to the individual. •Dealing with anxiety and uncertainty

• Compensating for a possible lack of structure in community services

• Learning how to initiate new developments

• Managing opposition to change within the mental health system

• Responding to opposition from neighbors

• Negotiating financial obstacles

• Bridging boundaries and barriers

• Creating locally relevant services rather than copying solutions from elsewhere

• Avoiding system rigidities

• Maintaining staff morale • Ethics

• Evidence

• Experience

Source: Data from Thornicroft, Szmukler, Mueser, & Drake ( 2011).

According to the tenets of this approach, the community becomes the locus for and main provider of mental health care. Such treatment should take a holistic approach and also support the efforts of therapists and other individual clinicians. Examples of community settings for mental health care are community mental health centers (often branches of government health care agencies); sheltered halfway houses for persons who are recovering from mental illness; local primary care health services; day care and drop-in centers; and self-help groups such as those that provide counseling and therapy. The goal of these community settings should be to work collaboratively in order to provide seamless behavioral health care services for the treatment of mental disorders (see Table 9.4).

9.6 Prevention of Mental Disorders

This section provides a brief discussion of prevention of mental disorders. The public health model for prevention of disease involves primary, secondary, and tertiary prevention. In review, primary prevention involves the prevention of disease before it has occurred—before the agent has interacted with the host.

Secondary prevention involves screening for and early detection of diseases: An example from physical health is screening for breast cancer in order to arrest its development and prevent harmful sequelae. Regarding mental illness, secondary prevention should strive for early detection of disorders in order to initiate treatment early in their course and thereby prevent or limit disability from them. In order to increase their effectiveness, screening programs for mental disorders should be directed at individuals who are at high risk in comparison with the rest of the population. Examples of such high-risk persons include children and teenagers who are manifesting early symptoms of disorders (e.g., extreme and intractable behavioral disturbances in the classroom).

Ambient Images Inc./SuperStock

In Queens, New York, students create an anti-bullying mural. Such an undertaking is categorized as a primary prevention strategy.

Tertiary prevention, by definition, would focus mainly on rehabilitation of persons who have mental illnesses—for example, helping an individual to obtain appropriate housing and improve employment-related and social skills.

Of the three types of prevention, primary prevention is likely to be the most cost-effective means for reducing the burden of mental disorders. One example of primary prevention is called mental health promotion, which is highly relevant to community mental health. Mental health promotion is

the enhancement of the capacity of individuals, families, groups or communities to strengthen or support positive emotional, cognitive and related experiences. Other definitions have viewed mental health promotion is a reduction of morbidity from mental illness and the enhancement of the coping capacity of a member of a community. (WHO, 2002)

Specific actions related to primary prevention might include the protection of children from stresses such as parental abuse and school bullying. These kinds of experiences might increase future risk of disorders. Another example is limiting the exposure of fetuses, infants, and children to potentially toxic environmental chemicals and other disease-causing agents. A final example is for the community to encourage social connectedness and interaction among people.

Recall that mental disorders can result from interactions between genetic (and other constitutional) factors and the environment. Methods of mental health promotion directed toward improving the social and physical environment reduce the likelihood that persons who are at increased risk of mental disorders will go on to develop them.

Summary

This chapter gave an overview of mental disorders (e.g., anxiety disorder, bipolar disorder, depression, and schizophrenia) and described the impact of mental disorders upon the individual and the community. In the United States, more than one-quarter of the adult population is afflicted with mental illnesses during any given year. These disorders represent highly salient health issues for the community with respect to their associated burdens, economic costs, and adverse impacts upon families and society. Some of the observable concomitants of mental illness in the United States are homelessness, suicide among returning war veterans, and incarceration of persons who are mentally ill.

This chapter defined the term mental health and demonstrated its connection with overall health. Mental health and mental illness represent end points on a continuum that includes "mental health problems," which are not the same thing as mental illness. Data on the epidemiology of mental disorders reveal substantial variations according to age, sex, race, and socioeconomic status. The lifetime prevalence of any mental disorder is highest among persons in middle adulthood and is over 60%. Approximately 6% of the U.S. adult population has a serious mental disorder in any given year. Members of racial and ethnic minorities tend to receive less adequate care for mental disorders than Whites. Among the various categories of mental disorders, depression is the most frequently occurring disorder. Suicide was the 10th leading cause of death in the United States in 2009, with males more at risk than females.

The causes of mental illness are not understood fully. However, some disorders are known to be associated with family, social influences, environmental factors, stress, experience of trauma, and—in some instances—inherited characteristics. Treatments for mental disorders involve the use of prescription medications, psychotherapy, behavioral therapy, and cognitive–behavioral therapy. Community mental health care refers to making the community the locus for mental health services. Prevention of mental illness involves secondary prevention—screening high-risk persons—and primary prevention, or mental health promotion. Given the range of effective treatment options that are available, persons with mental illnesses can lead productive and satisfying lives.

Study Questions and Exercises

Describe the burden of mental disorders for the world and for the United States with respect to prevalence, economic costs, and personal impacts.

Define the following terms:

mental health

mental illness/mental disorder

depression

schizophrenia

Describe three goals of Healthy People 2020 for prevention of mental disorders.

What are some examples of the different types of mental illnesses and disorders that occur during different stages of life?

What are some of the mental health disparities that affect people from ethnic and racial minorities?

What conditions are considered to be anxiety disorders? Describe each one.

Define the term bipolar disorder. What are the principal symptoms of this disorder?

What are the distinguishing symptoms of major depression? What are some of the possible consequences of untreated major depression?

Define the following terms:

suicide

methods (of suicide)

suicidal behaviors

suicidal ideation

suicide attempt

Describe methods for the treatment of mental disorders including classes of medicines used for drug treatment. Why might some persons discontinue taking their prescribed medications?

Key Terms

Click on each key term to see the definition.

anorexia nervosa

anti-anxiety drugs

antidepressants

antipsychotic drugs

behavioral health care

binge-eating disorder

bipolar disorder

bulimia nervosa

deinstitutionalization

depression

generalized anxiety disorder (GAD)

mental health

mental illness

obsessive–compulsive disorder (OCD)

panic disorder

post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD)

schizophrenia

serious mental illness (SMI)

social phobia (social anxiety disorder)

suicide