Policy analysis: Prescribing policies

Figure 5.2

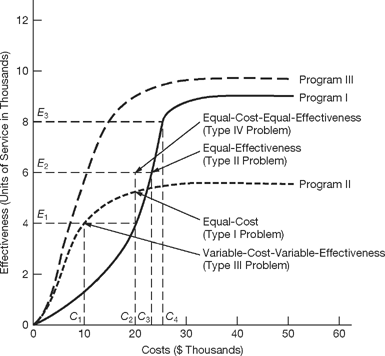

FIGURE 5.2 Cost-effectiveness comparisons using four criteria of adequacy. Source: Adapted from E. S. Quade, Analysis for Public Decisions (New York: American Elsevier, 1975), p. 93.

The different definitions of adequacy contained in these four types of problems point to the complexity of relationships between costs and effectiveness. For example, two programs designed to provide municipal services (measured in units of service to citizens) may differ significantly in terms of both effectiveness and costs (Figure 5.2). Program I achieves a higher overall level of effectiveness than program II, but program II is less costly at lower levels of effectiveness. Should the analyst prescribe the program that maximizes effectiveness (program I) or the program that minimizes costs at the same level of effectiveness (program II)?

To answer this question, we must look at the relation between costs and effectiveness, rather than view costs and effectiveness separately. Yet this is where the complications begin (see Figure 5.2): (1) If we are dealing with a type I (equal-cost) problem and costs are fixed at $20,000 (C2), program II is preferable because it achieves the higher level of effectiveness while remaining within the fixed-cost limitation. (2) If we are confronted with a type II (equal-effectiveness) problem and effectiveness is fixed at 6,000 units of service (E2), program I is preferable. (3) If, on the other hand, we are dealing with a type III (variable-cost-variable-effectiveness) problem, for which costs and effectiveness are free to vary, program II is preferable, because the ratio of effectiveness to costs (called an effectiveness-cost ratio) is greatest at the intersection of E1 and C1. Here program II produces 4,000 units of service for $10,000, that is, a ratio of 4,000 to 10,000 or 0.4. By contrast, program I has an effectiveness-cost ratio of 0.32 (8,000 units of service for $25,000 = 8,000/25,000 = 0.32).10 Finally, (4) if we are dealing with a type IV (equal-cost-equal-effectiveness) problem, for which both effectiveness and costs are fixed at E2 and C2, neither program is adequate. This dilemma, which permits no adequate solution, is known as criterion over specification. The lesson of this illustration is that it is seldom possible to choose between two alternatives on the basis of either costs or effectiveness. Although it is sometimes possible to convert measures of effectiveness into dollar benefits, which permits us to calculate net income benefits by subtracting monetary costs from monetary benefits, it is frequently difficult to establish convincing dollar equivalents for important policy outcomes. What is the dollar equivalent of a life saved through traffic safety programs? What is the dollar value of international peace and securiy promoted by United Nations educational, scientific, and cultural activities? What is the dollar value of natural beauty preserved through environmental protection legislation? Such questions will be examined further when we discuss cost-benefit analysis; but it is important here to recognize that the measurement of effectiveness in dollar terms is a complex and difficult problem.11 Sometimes it is possible to identify an alternative that simultaneously satisfies all criteria of adequacy. For example, the broken-line curve in Figure 5.2 (Program III) adequately meets fixed-cost as well as fixed-effectiveness criteria and also has the highest ratio of effectiveness to costs. As this situation is rare, it is almost always necessary to specify the level of effectiveness and costs that is regarded as adequate. Questions of adequacy cannot be resolved by arbitrarily adopting a single criterion. For example, net income benefits (dollars of effectiveness minus dollar costs) are not an appropriate criterion when costs are fixed and a single program with the highest benefit-cost ratio can be repeated many times. This is illustrated in Table 5.4, in which program I can be repeated 10 times up to a fixed-cost limit of $40,000, with total net benefits of $360,000 (i.e., $36,000 × 10). Program I therefore has the highest benefit-cost ratio. But if program I cannot be repeated—that is, if only one of the three programs must be selected—program III is preferable because it yields the greater net benefits, even though it has the lowest benefit-cost ratio. Equity. The criterion of equity is closely related to legal and social rationality and refers to the distribution of effects and effort among different groups in society. An equitable policy is one for which effects (e.g., units of service or monetary benefits) or efforts (e.g., monetary costs) are fairly or justly distributed. Policies designed to redistribute income, educational opportunity, or public services are sometimes prescribed on the basis of the criterion of equity. A given program might be effective, efficient, and adequate—for example, the benefit-cost ratio and net benefits may be superior to those of all other programs—yet it might still be rejected on grounds that it will produce an inequitable distribution of costs and benefits. This could happen under several conditions: Those most in need do not receive services in proportion to their numbers, those who are least able to pay bear a disproportionate share of costs, or those who receive most of the benefits do not pay the costs. The criterion of equity is closely related to competing conceptions of justice or fairness and to ethical conflicts surrounding the appropriate basis for distributing resources in society. Such problems of “distributive justice,” which have been widely discussed since the time of the ancient Greeks, may occur each time a policy analyst prescribes a course of action that affects two or more persons in society. Although we may seek a way to measure social welfare, that is, the aggregate satisfaction experienced by members of a community. Yet individuals and groups within any community are motivated by different values, norms, and institutional rules. What satisfies one person or group often fails to satisfy another. Under these circumstances, the analyst must consider a fundamental question: How can a policy maximize the welfare of society, and not just the welfare of particular individuals or groups? The answer to this question may be pursued in several different ways: 1. Maximize individual welfare. The analyst can attempt to maximize the welfare of all individuals simultaneously. This requires that a single transitive preference ranking be constructed on the basis of all individual values. Arrow’s impossibility theorem, as we have seen, demonstrates that this is impossible even when there are only two persons and three alternatives. 2. Protect minimum welfare. The analyst can attempt to increase the welfare of some persons while still protecting the positions of persons who are worse off. This approach is based on the Pareto criterion, which states that one social state is better than another if at least one person is better off, and no one is worse off. A Pareto optimum is a social state in which it is not possible to make any person better off without also making another person worse off. 3. Maximize net welfare. The analyst can attempt to increase net welfare (e.g., total benefits less total costs) but assumes that the resulting gains could be used to compensate losers. This approach is based on the Kaldor-Hicks criterion: One social state is better than another if there is a net gain in efficiency (total benefits minus total costs) and if those who gain can compensate losers. For all practical purposes, this criterion, which does not require that losers actually be compensated, avoids the issue of equity. 4. Maximize redistributive welfare. The analyst can attempt to maximize redistributional benefits to selected groups in society, for example, the racially oppressed, poor, or sick. One redistributive criterion has been put forth by philosopher John Rawls: One social state is better than another if it results in a gain in welfare for members of society who are worst off.12