| Choose one of the below for your main post. The answers should come from your textbook, the lectures, videos, and the research you conducted in the APUS Library. ![respond to assign 2 1]() This 1899 photograph of students at the Hampton Institute in Virginia was taken by Frances Benjamin Johnston. It is from Artstor.org. 1.) In Plessy versus Ferguson, what were the arguments for "separate but equal" legislation? What were the arguments against this legislation? What is a dissent? What are the implications of Harlan's dissent? What is Harlan's fundamental objection to the decision? What is Harlan's view of legal distinctions based on racial considerations? What does he feel will be the consequences of this decision? What does the Court say is the underlying fallacy of the plaintiff's argument? Give three examples during this time in which state legislation sustained separation. Make sure you read about the Plessy case. 2.) Explain: Legislation "is powerless to eradicate racial instincts or to abolish distinctions based upon physical differences, and the attempt to do so can only result in accentuating the difficulties of the present situation." What effect did Plessy versus Ferguson have? Make sure you read about the Plessy case. 3.) How and why had blacks, particularly in the South, been subjected to second-class citizenship by 1900? Why were Jim Crow laws predominantly in the South? How did Jim Crow happen? Make sure you read about the Plessy case. 4.) Analyze how African Americans were challenging white supremacy before World War I. Make sure you read about the Plessy case. Note: Sometime this week, in one of your posts, reflect on what, in all your required work, you learned new, surprising, and interesting. If you cannot clearly demonstrate you have learned from all the required work in one of those three posts, then write this fourth post summarizing what you have learned from the required work. This is your opportunity, if you have not had a chance in your various posts, to demonstrate that you have done all the required work for this week. The photograph is by Frances Benjamin Johnston. This is an 1899 dressmaking class at the Hampton Institute in Virginia. It comes from artstor.org. 1.) Read Kelley and Lewis, Chapter One. 2.) Read Plessy v. Ferguson Case Summary. FindLaw » US Supreme Court Center » Supreme Court » US Supreme Court Filing Guides » PLESSY v. FERGUSON (1896) PLESSY v. FERGUSON (1896) MAIN | cases | docket | decisions | orders | briefs | rules | guides | calendar ![respond to assign 2 2]()

Background After the Civil War, the South enacted black codes to keep their former slaves under tight control. For example, some states prohibited blacks, who were not a party to a suit, from testifying in court. Others subjected blacks to criminal penalties for breaching labor contracts. In contrast, whites were only liable in a civil suit for the same action. To strike down these black codes, the nation passed the Fourteenth Amendment, which prohibits states from denying "to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws." During the years that followed, the Supreme Court attempted to define the parameters of equal protection. In Strauder v. West Virginia (1879), the Court struck down the murder conviction of the petitioner, a colored man, because the state only permitted "white males who are twenty-one years of age and who are citizens of this State" to serve as jurors. The Court found that the state denied the petitioner the equal protection of the laws because it compelled him "to submit to a trial for his life by a jury drawn from a panel from which the State has expressly excluded every man of his race." The Court added, "The very fact that colored people are singled out and expressly denied by a statute all right to participate in the administration of the law, as jurors, because of their color, though they are citizens, and may be in other respects fully qualified, is practically a brand upon them, affixed by the law, an assertion of their inferiority, and a stimulant to that race prejudice which is an impediment to securing to individuals of the race that equal justice which the law aims to secure to all others." In 1896, the Court was presented with another opportunity to hear an equal protection case. This time, the petitioner challenged a Louisiana statute, which prohibited persons from occupying seats in railway coaches, "other than the ones assigned to them, on account of the race" to which they belong. Persons violating this statute may be subject to a fine or imprisonment.

Separate But Equal

On June 7, 1892, Homer Plessy, a 30-year-old shoemaker, boarded a passenger train of the East Louisiana Railway and took a seat in the "white" railcar. When he refused a conductor's orders to move to the "colored" railcar, Plessy was forcibly removed and jailed. Plessy argued that the Louisiana statute violated, among others, the Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution. After the state courts found the railcar statute to be constitutional, Plessy petitioned the United States Supreme Court, which upheld the lower court rulings. ![respond to assign 2 3]()

In the majority opinion, Justice Brown distinguished between political and social equality. The Justice explained that the purpose of the Fourteenth Amendment was only "to enforce the absolute equality of the two races before the law," and not to enforce social equality or "a commingling of the two races upon terms unsatisfactory to either." Moreover, "[l]aws permitting, and even requiring, their separation, in places where they are liable to be brought into contact," such as with the establishment of separate white and colored schools, do not necessarily imply the inferiority of either race to the other, and have been generally, if not universally, recognized as within the competency of the state legislatures . . . ." Accordingly, "[w]hen the government, therefore, has secured to each of its citizens equal rights before the law, and equal opportunities for improvement and progress, it has accomplished the end for which it was organized, and performed all of the functions respecting social advantages with which it is endowed."

Lone Dissenter

The lone dissenter, Justice John Harlan, declared, "Our Constitution is color-blind, and neither knows nor tolerates classes among citizens. In respect of civil rights, all citizens are equal before the law." He then predicted that "[t]he sure guaranty of the peace and security of each race is the clear, distinct, unconditional recognition by our governments, national and state, of every right that inheres in civil freedom, and of the equality before the law of all citizens of the United States, without regard to race." Justice Harlan concluded by condemning the majority opinion. "In my opinion, the judgment this day rendered will, in time, prove to be quite as pernicious as the decision made by this tribunal in the Dred Scott Case."

Aftermath

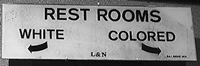

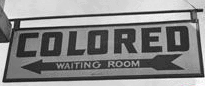

While the majority opinion did not use the phrase "separate but equal," it effectively approved of legally enforced segregation as long as the law did not make facilities for blacks inferior to those of whites. This "separate but equal" doctrine soon extended to other areas of public life, such as restaurants, theaters, restrooms, and public schools. It was not until 1954, in another landmark case, Brown v. Board of Education, that the Supreme Court finally closed this disgraceful chapter in American History. The Full Supreme Court Opinion Back to Landmark Cases Index 3.) Read Booker T. Washington's "Atlanta Compromise." Booker T. Washington Delivers the 1895 Atlanta Compromise Speech On September 18, 1895, African-American spokesman and leader Booker T. Washington spoke before a predominantly white audience at the Cotton States and International Exposition in Atlanta. His “Atlanta Compromise” address, as it came to be called, was one of the most important and influential speeches in American history. Although the organizers of the exposition worried that “public sentiment was not prepared for such an advanced step,” they decided that inviting a black speaker would impress Northern visitors with the evidence of racial progress in the South. Washington soothed his listeners’ concerns about “uppity” blacks by claiming that his race would content itself with living “by the productions of our hands.” Mr. President and Gentlemen of the Board of Directors and Citizens: One-third of the population of the South is of the Negro race. No enterprise seeking the material, civil, or moral welfare of this section can disregard this element of our population and reach the highest success. I but convey to you, Mr. President and Directors, the sentiment of the masses of my race when I say that in no way have the value and manhood of the American Negro been more fittingly and generously recognized than by the managers of this magnificent Exposition at every stage of its progress. It is a recognition that will do more to cement the friendship of the two races than any occurrence since the dawn of our freedom. Not only this, but the opportunity here afforded will awaken among us a new era of industrial progress. Ignorant and inexperienced, it is not strange that in the first years of our new life we began at the top instead of at the bottom; that a seat in Congress or the state legislature was more sought than real estate or industrial skill; that the political convention or stump speaking had more attractions than starting a dairy farm or truck garden. A ship lost at sea for many days suddenly sighted a friendly vessel. From the mast of the unfortunate vessel was seen a signal,“Water, water; we die of thirst!” The answer from the friendly vessel at once came back, “Cast down your bucket where you are.” A second time the signal, “Water, water; send us water!” ran up from the distressed vessel, and was answered, “Cast down your bucket where you are.” And a third and fourth signal for water was answered, “Cast down your bucket where you are.” The captain of the distressed vessel, at last heeding the injunction, cast down his bucket, and it came up full of fresh, sparkling water from the mouth of the Amazon River. To those of my race who depend on bettering their condition in a foreign land or who underestimate the importance of cultivating friendly relations with the Southern white man, who is their next-door neighbor, I would say: “Cast down your bucket where you are”— cast it down in making friends in every manly way of the people of all races by whom we are surrounded. Cast it down in agriculture, mechanics, in commerce, in domestic service, and in the professions. And in this connection it is well to bear in mind that whatever other sins the South may be called to bear, when it comes to business, pure and simple, it is in the South that the Negro is given a man’s chance in the commercial world, and in nothing is this Exposition more eloquent than in emphasizing this chance. Our greatest danger is that in the great leap from slavery to freedom we may overlook the fact that the masses of us are to live by the productions of our hands, and fail to keep in mind that we shall prosper in proportion as we learn to dignify and glorify common labour, and put brains and skill into the common occupations of life; shall prosper in proportion as we learn to draw the line between the superficial and the substantial, the ornamental gewgaws of life and the useful. No race can prosper till it learns that there is as much dignity in tilling a field as in writing a poem. It is at the bottom of life we must begin, and not at the top. Nor should we permit our grievances to overshadow our opportunities. To those of the white race who look to the incoming of those of foreign birth and strange tongue and habits for the prosperity of the South, were I permitted I would repeat what I say to my own race,“Cast down your bucket where you are.” Cast it down among the eight millions of Negroes whose habits you know, whose fidelity and love you have tested in days when to have proved treacherous meant the ruin of your firesides. Cast down your bucket among these people who have, without strikes and labour wars, tilled your fields, cleared your forests, builded your railroads and cities, and brought forth treasures from the bowels of the earth, and helped make possible this magnificent representation of the progress of the South. Casting down your bucket among my people, helping and encouraging them as you are doing on these grounds, and to education of head, hand, and heart, you will find that they will buy your surplus land, make blossom the waste places in your fields, and run your factories. While doing this, you can be sure in the future, as in the past, that you and your families will be surrounded by the most patient, faithful, law-abiding, and unresentful people that the world has seen. As we have proved our loyalty to you in the past, in nursing your children, watching by the sick-bed of your mothers and fathers, and often following them with tear-dimmed eyes to their graves, so in the future, in our humble way, we shall stand by you with a devotion that no foreigner can approach, ready to lay down our lives, if need be, in defense of yours, interlacing our industrial, commercial, civil, and religious life with yours in a way that shall make the interests of both races one. In all things that are purely social we can be as separate as the fingers, yet one as the hand in all things essential to mutual progress. There is no defense or security for any of us except in the highest intelligence and development of all. If anywhere there are efforts tending to curtail the fullest growth of the Negro, let these efforts be turned into stimulating, encouraging, and making him the most useful and intelligent citizen. Effort or means so invested will pay a thousand per cent interest. These efforts will be twice blessed—blessing him that gives and him that takes. There is no escape through law of man or God from the inevitable: The laws of changeless justice bind Oppressor with oppressed; And close as sin and suffering joined We march to fate abreast... Nearly sixteen millions of hands will aid you in pulling the load upward, or they will pull against you the load downward. We shall constitute one-third and more of the ignorance and crime of the South, or one-third [of] its intelligence and progress; we shall contribute one-third to the business and industrial prosperity of the South, or we shall prove a veritable body of death, stagnating, depressing, retarding every effort to advance the body politic. Gentlemen of the Exposition, as we present to you our humble effort at an exhibition of our progress, you must not expect overmuch. Starting thirty years ago with ownership here and there in a few quilts and pumpkins and chickens (gathered from miscellaneous sources), remember the path that has led from these to the inventions and production of agricultural implements, buggies, steam-engines, newspapers, books, statuary, carving, paintings, the management of drug stores and banks, has not been trodden without contact with thorns and thistles. While we take pride in what we exhibit as a result of our independent efforts, we do not for a moment forget that our part in this exhibition would fall far short of your expectations but for the constant help that has come to our educational life, not only from the Southern states, but especially from Northern philanthropists, who have made their gifts a constant stream of blessing and encouragement. The wisest among my race understand that the agitation of questions of social equality is the extremest folly, and that progress in the enjoyment of all the privileges that will come to us must be the result of severe and constant struggle rather than of artificial forcing. No race that has anything to contribute to the markets of the world is long in any degree ostracized. It is important and right that all privileges of the law be ours, but it is vastly more important that we be prepared for the exercise of these privileges. The opportunity to earn a dollar in a factory just now is worth infinitely more than the opportunity to spend a dollar in an opera-house. In conclusion, may I repeat that nothing in thirty years has given us more hope and encouragement, and drawn us so near to you of the white race, as this opportunity offered by the Exposition; and here bending, as it were, over the altar that represents the results of the struggles of your race and mine, both starting practically empty-handed three decades ago, I pledge that in your effort to work out the great and intricate problem which God has laid at the doors of the South, you shall have at all times the patient, sympathetic help of my race; only let this be constantly in mind, that, while from representations in these buildings of the product of field, of forest, of mine, of factory, letters, and art, much good will come, yet far above and beyond material benefits will be that higher good, that, let us pray God, will come, in a blotting out of sectional differences and racial animosities and suspicions, in a determination to administer absolute justice, in a willing obedience among all classes to the mandates of law. This, coupled with our material prosperity, will bring into our beloved South a new heaven and a new earth. 4.) View Without Sanctuary: This is a short 5-minute film that gives you a history of lynching through postcards from the era. Please note that you should censor this film from children because it is graphic. 5.) Watch one of these lectures: Professor Jonathan Holloway, "Uplift, Accommodation, and Assimilation," part one. Professor Jonathan Holloway, "Uplift, Accommodation, and Assimilation," part two. Professor David Jackson, Booker T. Washington and the Southern Education Tour, 1908-1912.

6.) Go to the Week 2 Form (Forum #2) and read the questions. Post your answers, incorporate evidence that you have done all the required work. Your response must be at least 300 words.

8.) Submit your formal essay for the group follow-up; at least 300 words 10.) Read the lesson for this week. |

New! Question 3

Mark as Read

Reply

Mark as Read

Reply