Qualitative Methodologies Qualitative methodologies involve collecting non-numerical data, usually through interviews or observation. There are many approaches to qualitative research and no fully agr

Required Text

Malec, T. & Newman, M. (2013). Research methods: Building a knowledge base. San Diego, CA: Bridgepoint Education, Inc. ISBN-13: 9781621785743, ISBN-10: 1621785742.

Section 1.6 Writing a Research Proposal

Chapter 3: Qualitative and Descriptive Designs – Observing Behavior

Section 5.3: Experimental Validity: A Note on Qualitative Research Validity and Reliability

Appendix: Example of a Research Proposal

1.6 Writing a Research Proposal

After reviewing the literature and putting considerable thought into planning a study, the next step is to prepare a research proposal. The goalof any research proposal is to present a detailed description about the research problem and the methods with which you think that theresearch should be conducted. Research proposals are extremely important because they are key to unlocking the research project (Leedy &Ormrod, 2010). They may determine whether you receive approval or funding, so they need to clearly articulate the purpose of the researchand persuade the audience it is worthwhile. If research proposals do not clearly and specifically define the research problem and methods, theproject might not be accepted. Therefore, it is imperative that the research proposal include "a clearly conceived goal and thorough, objectiveevaluation of all aspects of the research endeavor" (Leedy & Ormrod, 2010, p. 117).

Research proposals can range from three pages for some grant applications to more than 30 pages (e.g., for a dissertation or federal grant).They may or may not require an abstract and will have a different format for institutional review board (IRB) approval (see Section 1.7, Ethics inResearch). For our purposes, in general, research proposals follow a standard format. The following is an example you might use:

Title/Cover Page

Abstract

Introduction or Statement of the Problem

The research problem

The statement of the problem and possible subproblems

The purpose statement

Hypotheses and/or research questions

Independent and dependent variables

The assumptions

The importance of the study

Review of the Literature

Method

Research methodology

Participants and participant selection

Data collection procedures

Data analysis techniques

Discussion

Strengths and limitations

Ethical considerations

References

Appendixes

Research proposals are written like research articles in APA style, which is favored in academia. The language must be clear and precise, inparagraph format, and written in a professional, academic manner. Unlike stories or memoirs, proposals are not intended to be creative literaryworks; rather, they should set down certain facts. Organized with headings and subheadings, the proposal should clearly and specifically explainthe research problem, who the participants will be and how they will be selected, what data collection methods will be used, and how the datawill be analyzed and interpreted. Research proposals are required for all theses and dissertations. If you are currently working on a master'sthesis or doctoral dissertation, your university or committee chair may have a specific format for you to follow that may differ slightly from theformat presented in this book. An example of an APA formatted proposal is provided in the Appendix.

Formatting the Research Proposal

As mentioned previously, research proposals are written in APA style and follow an organized format. Although there are different ways toformat a proposal, most follow a similar format to the one that is discussed in this book. The following sections will discuss the specifics offormatting of your proposal as well as the content that should be included within each section.

Headings and Subheadings

Writing a proposal in APA style may seem complicated at first; however, the format is similar to a research paper or any academic paper that isrequired to be written in APA style. APA style uses a unique heading and subheading system that separates and classifies sections of researchpapers. The Publication Manual of the American Psychological Association Sixth Edition (2010) utilizes five heading levels; although all headinglevels may not be used, it is important to follow them in sequential order:

Level 1: Centered, Boldface, Uppercase and Lowercase Heading

Level 2: Left-aligned, Boldface, Uppercase and Lowercase Heading

Level 3: Indented five spaces, boldface, lowercase heading with a period. For Level 3 headings, the body text begins after the period.

Level 4: Indented five spaces, boldface, italicized, lowercase heading with a period. For Level 4 headings, the body text begins after theperiod.

Level 5: Indented five spaces, italicized, lowercase heading with a period. For Level 5 headings, the body text begins after the period.

Section headings such as Review of the Literature, Methods, and so forth, are Level 1 headings. Subsection headings such as Participants, DataCollection, and so on, that follow under the section heading Methods, for example, are Level 2 headings. Subsections of subsection headings areLevel 3 through Level 5. The following is an example of the various heading levels you might use in your research proposal:

| Introduction (Level 1) |

| The Research Problem (Level 2) |

| Review of the Literature (Level 1) |

| The Cognitive Profile of Learning Disabilities in Reading (Level 2) |

| Method (Level 1) |

| Research Methodology (Level 2) |

| Discussion (Level 1) |

| Strengths and Limitations (Level 2) |

| References (Level 1) |

| Appendix (Level 1) |

The Title Page

A title page is required for all research proposals as its first page. In general, title pages include a running head with the page number, as wellas the abbreviated title of the paper, the student's name, and the university or institution name. Although some universities may have specificrequirements regarding how the title page is formatted, the following is formatted according to APA style:

| Running head: PREMORBID COGNITIVE ABILITIES |

Estimation of Premorbid Cognitive Abilities in

Children with Traumatic Brain Injury

Graduate Student

Research University

The running head is a shortened version of the full title and is included in the top margin of the page. The running head is set flush left withthe abbreviated title in all capital letters. On the same line of the running head, the page number is set flush right. The title of the paper, thestudent's name, and the university affiliation are centered approximately in the middle of the page and formatted in uppercase and lowercaseletters. It is recommended that titles include no more than 12 words.

The Abstract Page

The abstract page is page two of your paper. An abstract is a summary of your proposal and should include the research problem, theparticipants, data collection methods, and any hypotheses or research questions. Abstracts for research proposals are generally between 150and 250 words in length.

The abstract should contain your running head title from the title page as well as the page number. As shown in the example, the first word ofthe abstract is not indented. Thus, the entire abstract is set flush left. Please keep in mind that the title "running head" is dropped after pageone and only the abbreviated title and page number are included, as shown below:

| PREMORBID COGNITIVE ABILITIES |

Abstract

The present study will review currently available methods for estimating premorbid intellectual abilities inchildren. It examines the potential of the Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children–Fourth Edition (WISC–IV;Wechsler, 2003) as an estimate of premorbid IQ in children with traumatic brain injury (TBI). Archival data willbe obtained from a sample of 2,200 children aged 6:0–16:11 who participated in the standardization phase ofthe WISC–IV and 43 children aged 6:0–16:11 with a history of moderate or severe TBI who participated in aWISC–IV special group study. First, demographic variables including sex, ethnicity, parent education level, andgeographic region will be entered into a regression analysis to determine a demographic-based premorbidprediction equation for the WISC–IV Full Scale Intelligence Quotient (FSIQ). Second, a logistic regressionanalysis will be used to investigate which WISC–IV subtest–scaled scores improve the differential diagnosis ofTBI versus a matched control group. Third, analysis of variance (ANOVA) will be used to examine whichsubtests yielded the lowest mean scores for the TBI group. It is expected that parental education will be thestrongest predictor of premorbid IQ and that individuals with TBI will have lower scores on Processing Speedand Working Memory indices.

The Introduction Section

The Introduction section begins on page three of your proposal. The primary purpose of the Introduction section is to introduce the reader tothe nature of the study by including necessary background that describes and supports your research problem. The introduction generallyincludes a statement of the research problem, any potential subproblems, the purpose statement, hypotheses and/or research questions,identification of the variables, assumptions of the study, and importance of the study. The introduction typically begins with a statement of theresearch problem area and is followed by a justification for your proposed study. Only research needed to explain the purpose of or need foryour study should be included in this section.

As discussed previously, the purpose statement should include the focus, population, and methodology of the study. Depending upon whetheryour research is quantitative or qualitative, you will want to include your hypotheses and/or research questions next and discuss how yourhypotheses and/or research questions relate to your research problem and purpose statement. You should next review the key independent anddependent variables, followed by a discussion of the assumptions you will make about the research and how the research will be expected tocontribute to the field.

The length of the introduction can vary based on your university, committee chair, or instructor's requirements. In general, the introductionsection ranges anywhere from 3 to 5 pages to 15 to 25 pages. The more detailed information you include in your proposal, the closer you willbe to completing your thesis or dissertation.

The Literature Review Section

The primary purpose of the literature review is to provide theoretical perspectives and previous research findings on the research problem youhave selected (Leedy & Ormrod, 2010). As a researcher, you should investigate your topic extremely well so that you have a thoroughunderstanding about the research problem area. Thus, your literature review should contain both breadth and depth, and clarity and rigor, inorder to support the need for your research to be conducted. Any reader of your literature review should be able to comprehend theimportance of your research problem and the difference the research will make to the field. Keep in mind that a literature review is not simplya collection of summaries, abstracts, or annotated bibliographies but rather a thorough analysis and synthesized review of the research and howeach piece of research builds upon the other.

According to Levy and Ellis (2006), a literature review should go through the following steps: (a) methodologically analyze and synthesize qualityliterature, (b) provide a firm foundation to a research topic, (c) provide a firm foundation to the selection of research methodology, and (d)demonstrate that the proposed research contributes something new to the overall body of knowledge or advances the research field'sknowledge base (p. 182). Remember: Your literature review should provide a theoretical foundation and justification for your proposed study.

A good literature review does not simply report the literature but evaluates, organizes, and synthesizes it (Leedy & Ormrod, 2010). Whenreading and reviewing existing literature, it is important to critically evaluate what has already been done and what the findings showed. Do notjust take what the authors say at face value; instead, evaluate whether the findings support the methods that were used and the analyses thatwere conducted.

In addition to evaluating the literature, you must organize it. This means grouping the literature according to your subproblem areas, researchquestions, or variables being assessed. For example, if conducting a study on the demographic predictors of special education, you would wantto group your literature based on the various demographic variables and the influences that they may have on placement in special education.Finally and most importantly, you must synthesize the diverse perspectives and research results you've read into a cohesive whole (Leedy &Ormrod, 2010). Leedy and Ormrod (2010) discuss several approaches to synthesizing information, including the following:

comparing and contrasting the literature

showing how the literature has changed over time

identifying trends or similarities in research findings

identifying discrepancies or contradictions in research findings

locating similar themes across the literature

The following example shows a paragraph synthesizing the literature. Note that the review does not include summaries of the articles but ratherdisplays similarities found in the research:

Several studies have examined the relationship between demographic variables and cognitive functioning.Research has shown that demographic variables such as socioeconomic status and education level are closelyrelated to scores on cognitive tests and contribute significantly to variance in IQ scores (Crawford, 1992;Kaufman, 1990). Utilizing this close relationship, Wilson et al. (1978) developed the first regression equation topredict premorbid IQ using the WAIS standardization sample. The equation included age, sex, race, education,and occupation and accounted for 53% of the variance in the Verbal IQ, 42% of the variance in thePerformance IQ, and 54% of the variance in the Full Scale IQ. Cross-validation studies have confirmed theWilson et al. equation to be a useful predictor of premorbid IQ. The equation has been used to predictoutcome from closed head injury (Williams, Gomes, Drudge, & Kessler, 1984), to estimate British WAIS scores(Crawford, Stewart et al., 1989), and to estimate premorbid functioning among healthy adults (Goldstein, Gary,and Levin, 1986). Although the use and application of Wilson's formula has tended to overpredict high scoresand underpredict low scores, the formula appears to provide adequate predictions for those within theaverage range of functioning.

An example of a compare-and-contrast synthesized review would look like the following:

As with all regression-based methods, a number of limitations are present in the use of demographic-basedprediction models. As Karzmark, Heaton, Grant, and Matthews (1985) found in their use of the Wilson et al.formula to predict WAIS IQ scores, demographic equations tend to overestimate and underestimate IQ scoresfor individuals who are one standard deviation or more from the population mean. Research has shown strongcorrelations between specific demographic variables and measured IQ scores, but Bolter, Gouvier, Veneklasen,and Long (1982) found the Wilson et al. equation to be limited in its ability to predict groups of head injuredindividuals and controls.

On the other hand, Wilson, Rosenbaum, and Brown (1979) compared the hold method of the DeteriorationIndex developed by Wechsler in 1958 against Wilson's 1978 demographic equation and found the Wilson et al.formula to have a 73% accuracy of classification, while the Wechsler method resulted in only 62% accuracy.Although the demographic-based method may have mixed results at an individual level, cross-validationstudies have shown them to do an adequate job of predicting mean IQ scores at the group level (Vanderploeg,1994).

Remember that writing a literature review takes time and organization. It is important that you thoroughly review the relevant literature youuncovered in your key term search. This can be a painstaking endeavor, but the search should not conclude until you are reasonably sure youhave researched all the critical viewpoints of your research problem. It is also helpful to develop an outline of topics you plan on addressing.

Finally, note that a good literature review is not plagiarized or copied and pasted from other sources, as the Internet makes so tempting. Whenreviewing literature, be sure you summarize the information in your own words and give credit where credit is due. It is sometimes helpful toread the literature and then develop summaries of the articles in your own words. You can then use these summaries to develop your literaturereview. Keep in mind that your literature review is a working draft that will be modified and perfected throughout the research process.

The Method Section

The method section includes a detailed description of the method of inquiry (quantitative, qualitative, or mixed design approach); researchmethodology used; the sample; data collection procedures; and data analysis techniques. The key purpose of the method section is to discussyour design and the specific steps and procedures you plan to follow in order to complete your study. A detailed description of methods isessential in any research proposal because it allows others to examine the efficacy of the study as well as replicate it in the future.

Research Methodology

This section discusses whether quantitative, qualitative, or a mixed design approach was used and the rationale for choosing this method ofinquiry. It also includes specific information on the selected research methodology. For example, will your study be utilizing experimentalmethods, quasi-experimental methods, or observational methods? And what is the purpose for selecting that method or methods? Rememberthat you should be making an argument and justifying the type of research methodology you plan to use, regardless of the type of inquiry.

Participants

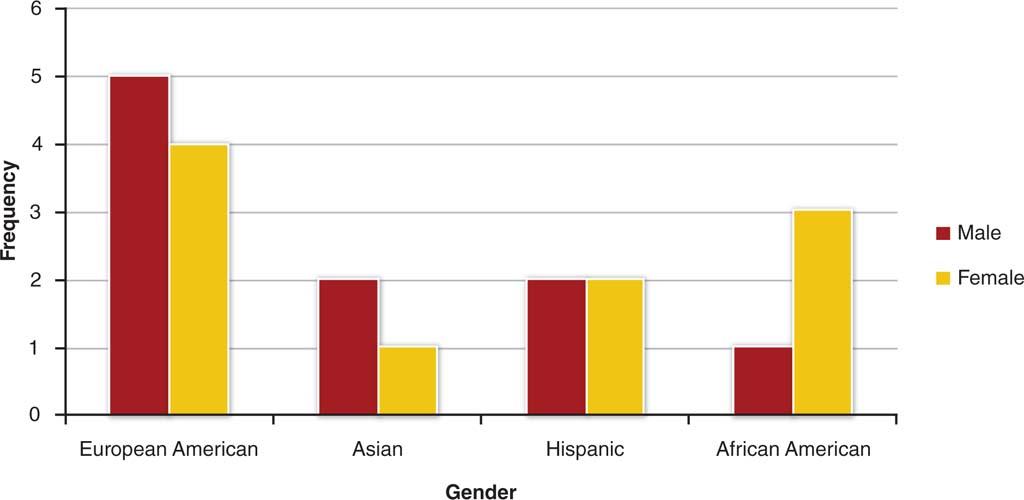

The participant section describes the population of interest and the sample that will be used. In quantitative studies, the sample is intended torepresent the larger population and tends to be larger in size than for qualitative studies. In qualitative studies, the sample may be a smallnumber of participants or even only one participant and is not intended to represent the larger population. In both quantitative and qualitativestudies, this section should discuss the sample in detail: the population you want to learn about; where participants will be recruited or studied;how the participants will be notified about the study; how the participants will be selected (e.g., what type of sampling method will be used,such as random sampling, snowball sampling, etc.); what criteria will be required for inclusion in the study (e.g., age, level of educationobtained, marital status, employment position); and the overall proposed size of the sample. For quantitative studies, when discussing thesample, it is also important to include which demographic information (e.g., age, gender, ethnicity, level of education, socioeconomic status) youwill need to create a representative sample of the entire population. A representative sample ensures that the results can be generalized to theentire population as a whole.

Data Collection Procedures

The data collection section describes how the data will be collected, step by step. This section should detail how informed consent will beobtained from the participants, when the data will be collected and for how long, and what methods or measures will be used to collect thedata. Remember: Providing detailed information is crucial to ensure that others can follow your study and replicate it in the future. Thus, thissection should include a step-by-step description of each of the procedures you will follow to carry out the data collection. Describe the datacollection forms you will use, as well as any survey, research, or testing instruments you may use or develop to collect the data, and therationale for utilizing such procedures. Copies of any forms or instruments used should be included in the Appendix section of your researchproposal.

Data Analysis

The data analysis section includes a brief step-by-step description of how the data will be analyzed as well as what statistical methods or othermethods of analysis and software will be utilized. If you are doing quantitative method research, you will want to discuss how the data will beentered into a statistical software program, how the data will be kept confidential, and what statistical analyses will be run. If using qualitativemethods, you will want to discuss the type of qualitative method used, the interview type, interview questions, sample type (e.g., random,convenience), how the data will be reviewed (e.g., how interviews or observations will be reviewed or transcribed), and how the data will becoded.

The Discussion Section

As emphasized throughout this chapter, one of the most important characteristics of a research proposal is to make a strong case for or justifythe need to study your research problem. In doing so, you will want to discuss the strengths of your research study as well as any limitationsand ethical issues that will need to be considered. It should be noted that some universities require this information to be included in theMethod section. In those cases, you would include strengths, limitations, and ethical considerations after the Data Analysis heading in theMethod section.

Strengths and Limitations

This section is fairly straightforward. It should discuss the implications for future research, practice, and theory as well as any potentiallimitations that might impact the research process or results. Some limitations may include difficulty in obtaining participants, difficulty inobtaining a representative sample, or time and financial constraints.

Ethical Considerations

This section should include any potential issues that might be considered ethical dilemmas. For example, if studying minors, how will you obtainconsent and ensure confidentiality? If studying certain employees, how will you keep information from their supervisors? Or if your study maytrigger emotional trauma, such as memories about abuse, how will you reduce any stress or negative feelings that occur during the study?

The References Section

This section should include all references that were cited within your proposal in alphabetical order and using APA style. Only references usedwithin your proposal should be included on the References page; conversely, there should be no references listed on the References page thatwere not cited in your proposal.

It is important to list all references in correct APA format. The following examples show how to correctly cite journal articles, websites, andbooks according to the APA Publication Manual Sixth Edition:

Example of a journal article with the document ID number included:

Brownlie, D. (2007). Toward effective poster presentations: An annotated bibliography. European Journal of Marketing, 41, 1245–1283.doi:10.1108/03090560710821161

Example of a journal article with no document ID assigned to it:

Kenneth, I. A. (2000). A Buddhist response to the nature of human rights. Journal of Buddhist Ethics, 8. Retrieved fromhttp://www.cac.psu.edu/jbe/twocont.html

Example of a print (or hardcopy) journal article:

Harlow, H. F. (1983). Fundamentals for preparing psychology journal articles. Journal of Comparative and Physiological Psychology, 55, 893–896.

Example of a textbook:

Calfee, R. C., & Valencia, R. R. (1991). APA guide to preparing manuscripts for journal publication. Washington, DC: American PsychologicalAssociation.

Example of a chapter in a textbook:

O'Neil, J. M., & Egan, J. (1992). Men's and women's gender role journeys: A metaphor for healing, transition, and transformation. In B. R.Wainrib (Ed.), Gender issues across the life cycle (pp. 107–123). New York, NY: Springer.

Example of a website:

Keys, J. P. (1997). Research design in occupational education. Retrieved from http://www.okstate.edu

The Appendix Section

The Appendix section should include a copy of any forms that will be used during your research. These include consent forms, instructions forparticipants, and any additional tables or figures that might supplement study information but not provide additional data (e.g., a table ofsubtests included within an instrument you plan to use).

Chapter 3

Qualitative and Descriptive Designs—ObservingBehavior

John Foxx/Stockbyte/Thinkstock

Chapter ContentsQualitative and Descriptive Research Designs

Qualitative Research Interviews

Critiquing a Qualitative Study

Writing the Qualitative Research Proposal

Describing Data in Descriptive Research

In the fall of 2009, Phoebe Prince and her family relocated from Ireland to South Hadley, Massachusetts. Phoebe was immediately singled outby bullies at her new high school and subjected to physical threats, insults about her Irish heritage, and harassing posts on her Facebook page.This relentless bullying continued until January of 2010, ending only because Phoebe elected to take her own life in order to escape hertormentors (United Press International, 2011). Tragic stories like this one are all too common, and it should come as no surprise that theCenters for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) have identified bullying as a serious problem facing our nation's children and adolescents(Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC], 2012).

Scientific research on bullying began in Norway in the late 1970s in response to a wave of teen suicides. Work begun by psychologist DanOlweus—and since continued by many others—has documented both the frequency and the consequences of bullying in the school system.Thus, we know that approximately one third of children are victims of bullying at some point during development, with between 5% and 10%bullied on a regular basis (Griffin & Gross, 2004; Nansel et al., 2001). Victimization by bullies has been linked to a wide range of emotional andbehavioral problems, including depression, anxiety, self-reported health problems, and an increased risk of both violent behavior and suicide (fora detailed review, see Griffin & Gross, 2004). Recent research even suggests that bullying during adolescence may have a lasting impact on thebody's physiological stress response (Hamilton et al., 2008).

But most of this research has a common limitation: It has studied the phenomenon of bullying using self-report survey measures. That is,researchers typically ask students and teachers to describe the extent of bullying in the schools or have students fill out a collection of surveymeasures, describing in their own words both bullying experiences and psychological functioning. These studies are conducted rigorously, andthe measures they use certainly meet the criteria of reliability and validity that we discussed in Chapter 2 (Section 2.2, Reliability and Validity).However, as Wendy Craig, Professor of Psychology at Queen's University, and Debra Pepler, a Distinguished Professor at York University,suggested in a 1997 article, this questionnaire approach is unable to capture the full context of bullying behaviors. And, as we have alreadydiscussed, self-report measures are fully dependent on people's ability to answer honestly and accurately.

In order to address this limitation, Craig and Pepler (1997) decided to observe bullying behaviors as they occurred naturally on the playground.Among other things, the researchers found that acts of bullying occurred approximately every 7 minutes, lasted only about 38 seconds, andtended to occur within 120 feet of the school building. They also found that peers intervened to try to stop the bullying more than twice asoften as adults did (11% versus 4%, respectively). These findings add significantly to scientific understanding of when and how bullying occurs.And for our purposes, the most notable thing about them is that none of the findings could have been documented without directly observingand recording bullying behaviors on the playground. By using this technique, the researchers were able to gain a more thorough understandingof the phenomenon of bullying and thus able to provide real-world advice to teachers and parents. Qualitative research is valuable when thenature of a phenomenon such as bullying, its signs, symptoms, dynamics, and emotional consequences are not well understood.

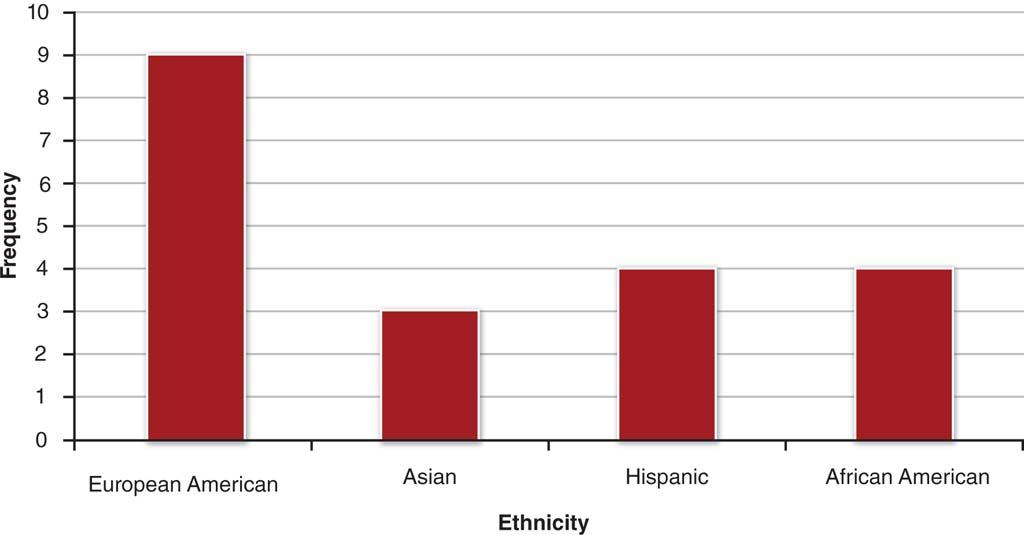

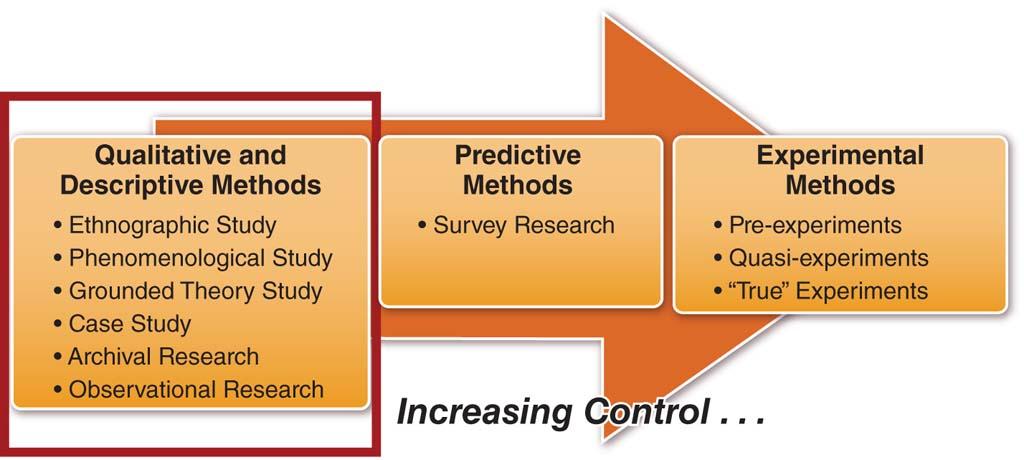

One recurring theme in this book is that it is absolutely critical to pick the right research design to address your hypothesis. Over the next threechapters, we will be discussing three specific categories of research designs, proceeding in order of increasing control over elements of thedesign: descriptive designs, quasi-experimental designs, and true experimental designs. This chapter will also focus on qualitative researchdesigns that have similar levels of control as the case study, in which the primary goal is to examine phenomena of interest in great detail. Wewill begin by discussing qualitative designs, including ethnography study, phenomenological study, and grounded theory study. We will thendiscuss three prominent examples of descriptive designs that can be used in either qualitative or quantitative approaches—case studies, archivalresearch, and observational research—covering the basic concepts, the pros and cons, and contrasting qualitative and quantitative approachesof each design (see Figure 3.1). We go on to discuss interview techniques and then offer guidelines for presenting descriptive data in graphical,numerical, and narrative form. Finally, we show how to critique a study and write a proposal for qualitative research projects.

Figure 3.1: Qualitative and descriptive research on the continuum of control

3.1 Qualitative and Descriptive Research Designs

We learned in Chapter 1 that researchers generally take one of two broad approaches to answering their research questions. Quantitativeresearch is a systematic, empirical approach that attempts to generalize results to other contexts, whereas qualitative research is a moredescriptive approach that attempts to gain a deep understanding of particular cases and contexts. Before we discuss specific examples of bothqualitative and descriptive designs, it is important to understand that descriptive designs can represent either quantitative or qualitativeperspectives, whereas qualitative designs represent only qualitative perspectives. In this section, we examine the qualitative and descriptiveapproaches in more detail.

In Chapter 1, we used the analogy of studying traffic patterns to contrast qualitative and quantitative methods—a quantitative researcher woulddo a "flyover" and perform a statistical analysis, whereas a qualitative researcher would likely study a single busy intersection in detail. Thisillustrates a key point about the latter approach. All qualitative approaches have two characteristics in common: (1) Focusing on phenomenathat occur in natural or real-world settings; and (2) studying those phenomena in their complexity.

Qualitative researchers focus on interpreting and making sense out of what they observe rather than trying to simplify and quantify theseobservations. In general, qualitative research involves collecting interviews, recordings, and observations made in a natural setting. Regardless ofthe overall approach (qualitative or quantitative), however, collecting data in the real world results in less control and structure than doescollecting data in a laboratory setting. But whereas quantitative researchers might view reduced control as a threat to reliability and validity,qualitative researchers view it as a strength of the study because the phenomenon of interest is being studied in its natural environment. Byconducting observations in a natural setting, it is possible to capture people's natural and unfiltered responses. The concepts of reliability andvalidity for both qualitative and quantitative approaches are discussed further in Chapter 5.

As an example, consider two studies on the ways people respond to traumatic events. In a 1993 paper, psychologists James Pennebaker andKent Harber took a quantitative approach to examining the community-wide impact of the 1989 Loma Prieta earthquake (centered in the SanFrancisco Bay Area). These researchers conducted phone surveys of 789 area residents, asking people to indicate, using a 10-point scale, howoften they "thought about" and "talked about" the earthquake during the 3-month period after its occurrence. In analyzing these data,Pennebaker and Harber discovered that people tend to stop talking about traumatic events about 2 weeks after they occur but keep thinkingabout the event for approximately 4 more weeks. That is, the event is still on people's minds, but they decide to stop discussing it with otherpeople. In a follow-up study using the 1991 Gulf War, these researchers found that this conflict between thoughts and their verbalization leadsto an increased risk of illness (Pennebaker & Harber, 1993). Thus, the goal of the study was to gather data in a controlled manner and test a setof hypotheses about community responses to trauma.

Contrast this approach with the more qualitative one taken by the developmental psychologist Paul Miller and colleagues (2012), who used aqualitative approach to study the ways that parents model coping behavior for their children. These researchers conducted semistructuredinterviews of 24 parents whose families had been evacuated following the 2007 wildfires in San Diego County and an additional 32 parentswhose families had been evacuated following a 2008 series of deadly tornadoes in Tennessee. Owing to a lack of prior research on how parentsteach their children to cope with trauma, Miller and colleagues approached their interviews with the goal of "documenting and describing" (p.8) these processes. That is, rather than attempt to impose structure and test a strict hypothesis, the researchers focused on learning from theseinterviews and letting the interviewees' perspectives drive the acquisition of knowledge.

Qualitative research is undertaken in many academic disciplines, including, psychology, sociology, anthropology, biology, education, history, andmedicine (Leedy & Ormrod, 2010). Although once frowned upon in the fields of psychology and education, due to their subjective nature,qualitative techniques have gained wide acceptance as legitimate research. In fact, many researchers argue that qualitative research is thebeginning step to all types of inquiry. Thus, qualitative research can explore unknown topics, unknown variables, and inadequate theory basesand thereby assist in the generating of hypotheses for future quantitative studies.

Unlike quantitative studies, qualitative studies do not allow the researcher to identify cause-and-effect relationships among variables. Rather, thefocus is on describing, interpreting, verifying, and evaluating phenomena, such as personal experiences, events, and behaviors, in their naturalenvironment. The most common forms of qualitative data collection techniques are observations, interviews, videotapes, focus groups, anddocument review. Creswell (2009) lists the following characteristics as generally present in most types of qualitative research:

Data collection occurs in the natural or real-world setting where participants experience the issue or problem being investigated.

The researcher is the key instrument used to collect data through means of examining documents, observing behavior, or interviewingparticipants.

Multiple sources of data are collected and reviewed.

As discussed in Chapter 1, qualitative researchers use inductive data analysis and build patterns and themes from the bottom up.

Focus is on understanding the participants' experiences, not on what the researcher believes those experiences mean.

The research process is emergent and can change after the researcher enters the field and begins collecting data.

Researchers as well as participants and readers interpret what they see, hear, and understand. This results in multiple views of the problem.

Researchers attempt to develop a complex picture of the problem under investigation, utilizing multiple methods of data collection.

Descriptive research does not fit neatly into the categories of either qualitative or quantitative methodologies; instead, it can utilize qualitative,quantitative, or a mixture of both methods to describe and interpret events, conditions, behaviors, feelings, and situations. In all cases,descriptive research investigates situations as they are, and similar to qualitative designs, does not involve changing (controlling) the situationunder investigation or attempting to determine cause-and-effect relationships. However, unlike qualitative designs, descriptive designs usuallyyield quantitative data that can be analyzed using statistical analyses. That is, descriptive research gathers data that describe events and thenorganizes, tabulates, depicts, and describes the collected data, often using visual aids such as graphs, tables, and charts.

Collecting data for descriptive research can be done with a single method or a variety of methods, depending upon the research questions. Themost common data collection methods utilized in descriptive research include surveys, interviews, observations, and portfolios. In general,descriptive research often yields rich data that can lead to important recommendations and findings.

In the following six sections, we examine six specific examples of qualitative and descriptive designs: ethnography, phenomenological studies,grounded theory studies, case studies, archival research, and observational research. The sections on ethnography, phenomenological studies,and grounded theory studies will focus specifically on the qualitative uses of these methods, since these are qualitative-only research methods.Because case studies, archival research, and observational research share the goals of describing attitudes, feelings, and behaviors, each one canbe undertaken from either a quantitative or a qualitative perspective. In other words, qualitative and quantitative researchers use many of thesame general methods but do so with different ends in mind. To illustrate this flexibility, we will end these three sections with a paragraph thatcontrasts qualitative and quantitative uses of the particular method.

Ethnography Study (Qualitative Design)

Ingram Publishing/Thinkstock

Employees who are part of an officeculture are an example of those whomight be studied in an ethnography.

Ethnographies were first developed by anthropologists to examine human society and various culturalgroups but are now frequently used in the sociology, psychology, and education fields. In fact, todayethnographies are probably the most widely used qualitative method for researching social and culturalconditions. Unlike case studies (which will be discussed later in this chapter) that examine a particularperson or event, ethnographies focus on an entire cultural group or a group that shares a commonculture. Although culture has various definitions, it usually refers to "the beliefs, values and attitudesthat shape the behavior of a particular group of people" (Merriam & Associates, 2002, p. 8). The conceptof what a culture is has also changed over time. Recently, more research has focused on smaller groups,such as classrooms and work offices, than on larger groups, such as northwest Alaskan Natives.

Regardless of whether the cultural group is a classroom or an entire ethnic group in a particular regionof the world, ethnographic research involves studying an entire community in order to obtain a holisticpicture of it. For example, in addition to studying behaviors, researchers will examine the economic,social, and cultural contexts that shape the community or were formed by the community.

In order to thoroughly study a particular cultural group, researchers will often immerse themselves in thecommunity. That is, the researcher will live in the study community for a prolonged period andparticipate in the daily routine and activities of those being studied. This is called participantobservation. Such prolonged involvement is necessary in order to observe and record processes thatoccur over time. Participant observation is an important data collection procedure in ethnographicresearch; thus, it is imperative that the researcher establish rapport and build trusting relationships withthe individuals he or she is studying (Hennink, Hutter, & Bailey, 2011). Establishing trusting relationshipscan be a quite lengthy process, which is why ethnographic studies usually span long periods of time.

Steps in Ethnographic ResearchSeveral steps are involved in conducting site-based research and data collection. First, the researcher must select a site or community that willaddress the research questions being asked. Because researchers should not have any expectations regarding the outcome of the study, it isbest if the researcher selects a site that he or she is not affiliated with. Selecting sites that the researcher is acquainted with may make itdifficult for him or her to study the group in an unbiased manner.

The next step involves gaining entry into the site. This can be a difficult task, as some researchers may not be well received. Therefore, asuccessful entrance into a site requires having access to a gatekeeper, an individual "who can provide a smooth entrance into the site" (Leedy &Ormrod, 2010, p. 139). Gatekeepers may include a principal of a school, a leader of a community, a director of a company, a tribal shaman, orany other well-respected leader of a particular cultural group.

Once inside the site, the researcher must take several delicate steps, including establishing rapport with individuals and forming trustingrelationships. As mentioned previously, establishing rapport is one of the most critical aspects of participant observation and provides afoundation for the quality and quantity of data that will be collected. Initially, establishing trust will involve interacting with everyone. At somepoint, however, the researcher will generally select key "informants" who can assist him or her in collecting the data. Finally, similar to all typesof research, the researcher will need to inform individuals about why he or she is there and the purpose of the study.

As with case studies, data collection and data analysis tend to occur simultaneously. Data collection may include making observations, obtainingrecordings, conducting interviews, and/or collecting records from the group. As the information is being collected, the researcher will readthrough it in great detail to obtain a general sense of what has been collected and to reflect on what all the data mean.

The next step is to organize the data based on events, issues, opinions, behaviors, and other factors and begin to analyze it by sorting the datainto categories. The categorized information will allow the researcher to observe any potential patterns or commonalities that may exist, as wellas to identify any key or critical events.

In addition to categorizing and observing patterns, the researcher will generally develop thick descriptions of the data, which "involves readingthe data and delving deeper into each issue by exploring its context, meaning, and the nuances that surround it" (Hennink, Hutter, & Bailey,2011, p. 239). For example, thick descriptions answer questions about the data such as, What is the issue? Why does it occur? When does itoccur? What are the perceptions about the issue? What are some explanations about the issue? and, Is the issue related to other data? Thickdescriptions provide additional information on potential connections and relationships that will be useful during data interpretation.

Pros and Cons of EthnographyThrough extensive and expansive investigation that is often personally involving for the researcher, ethnography allows the examination of aparticular cultural group in great detail. This method provides a holistic picture and understanding of the group as well as diverse aspects of it.It also allows great flexibility in the types of data collection methods that can be used. However, as we have seen, ethnographic researchrequires a long process of obtaining data and, therefore, can be quite expensive and time consuming. In addition, if one is not familiar with thevarious data collection methods, immersing oneself into a group without a clear idea of how to collect data from it can be overwhelming anddistracting.

As with all forms of participant observation, researcher bias and participant-expectancy bias (or the participant-observer effect) should beconsidered when examining the results of ethnographic research, and in all qualitative research for that matter. Researcher bias occurs whenthe researcher influences the results in order to portray a certain outcome. This type of bias can influence how the data are collected, as well ashow it is analyzed and interpreted. It can also impact what type of data is collected, how the data are categorized, and what types ofconclusions are drawn from the data analysis. For example, if a researcher is not able to lay aside his or her beliefs or assumptions, the type ofdata collected and the conclusions that are drawn could be biased or misleading. Also, we must take into account the influence that theresearcher has on the participants' behaviors and actions. Human nature being what it is, participants sometimes alter their normal behaviors tobe consistent with what they think the researcher is expecting from them or act differently simply because they are being observed.

Phenomenological Study (Qualitative Design)

Tyler Stableford/Iconica/Getty Images

Phenomenological studies attempt tounder-stand what it is like to experiencea certain event, such as returning homefrom war.

In the same way that ethnography focuses on cultural groups and their behaviors and experiences, a phenomenological study focuses on the person's perceptions and understandings of an experience. Aphenomenological study is one that attempts to understand the inner experiences of an event, such as aperson's perceptions, perspectives, and understandings (Leedy & Ormrod, 2010). Phenomenologicalstudies are concerned primarily with understanding what it is like to experience certain events. Forexample, researchers might be interested in studying the experiences of military spouses who havespouses deployed, wounded soldiers coming back from war, juvenile offenders' perceptions of thetherapeutic relationship in counseling, or elderly individuals being placed into a nursing home. In anysituation, the idea is to better understand the subjective or personal perspectives of different people asthey experience a particular event.

Some researchers conduct phenomenologicalstudies to obtain a more thorough understanding of anexperience that they have personally gone through. Looking at an experience or phenomenon frommultiple perspectives can allow them to generalize about what it is like to experience that phenomenon.However, regardless of the reason for wanting to conduct the research, it is important that the researcher set aside his or her personal beliefsand attitudes toward the experience in order to see and fully understand the essence of the phenomenon being studied (Merriam & Associates,2002).

Steps in Phenomenological ResearchPhenomenological research is generally conducted through in-depth, unstructured, and recorded interviews with a select participant sample (seeSection 3.2, Qualitative Research Interviews). The sample size is usually between 5 and 25 participants who have directly experienced thephenomenon being studied (Creswell, 1998). Unstructured interviews are conducted individually with each participant, which allows theresearcher to follow the participant's experiences thoroughly and ask spontaneous questions based on what is being discussed. Generally,unstructured interviews do not contain any predetermined questions, although some researchers develop a few questions to guide theinterview, which is acceptable in phenomenological research. Thus, a typical phenomenological interview is more like an informal conversation,although the participant does most of the talking and the researcher does most of the listening. In addition to listening, the researcher shouldalso note any meaningful facial expressions or body language, as these can provide additional information regarding the intensity of a feeling orthought.

In phenomenological studies, data are usually analyzed by identifying common themes across people's experiences. Themes are created by firsttranscribing the information from the interview in full and then editing to remove any unnecessary content. The next step is to group commonstatements from the interviews into categories that reflect the various aspects of the experience as well as to examine any divergentperspectives among subjects. The final step is to develop an overall description of how people experience the phenomenon (Leedy & Ormrod,2010).

Pros and Cons of Phenomenological StudiesPhenomenological studies give researchers a comprehensive view of a particular phenomenon, which is experienced by many but illumined bystudying the subjective responses of a few. Unstructured interviews provide a wealth of data while allowing participants to describe theirexperiences in their own way and under their own terms. Phenomenological studies are rich in personal experiences and provide a morecomplete or holistic view of what people experience.

Phenomenological studies can also be flawed if the interviews veer off topic or communication misunderstandings crop up. For example, somerecorded information may be difficult to understand. In addition, interviews, data analysis, and data interpretation can be influenced byresearcher bias regarding the experience. As mentioned previously, if a researcher has personally experienced the phenomenon being studied(rape would be an emotionally charged example), it is possible that he or she may bring preconceived notions or prejudices to the study, whichwill in turn influence how the data are collected and interpreted.

Grounded Theory Study (Qualitative Design)Unlike most qualitative research, grounded theory does not begin from a theoretical perspective or theory but rather utilizes data that arecollected to develop new theories or hypotheses. According to Smith and Davis (2010), "A grounded theory is one that is uncovered, developed,and conditionally confirmed through collecting and making sense of data related to the issue at hand" (p. 54). Thus, theories are built from"grounded" data that have been systematically analyzed and reanalyzed. Grounded theory is typically used in qualitative research; however,grounded theory can utilize either qualitative or quantitative data (Glaser, 2008), or a mixture of the two. As Glaser posits, grounded theory isnot only considered a qualitative method but a general method in research. For example, you may use grounded theory as the only method foryour qualitative study, or you may choose to use it as the first step toward identifying constructs and generating hypotheses about theirrelationships to one another. You may then want to employ a quantitative, cause-and-effect design to further test your hypotheses that weredeveloped from your grounded theory study.

Grounded theory is especially useful for exploring the relationships and behaviors of groups that either have not been previously studied orhave been inadequately studied. Grounded theory has been used to study a wide variety of topics, such as stress management in Olympicchampions (Fletcher & Sakar, 2012), the role of leaders in knowledge management (Lakshman, 2007), reflections of therapists during role-playing sessions (Rober, Elliot, Buysse, Loots, & Corte, 2008), normalizing risky sexual behaviors in female adolescents (Weiss, Jampol, Lievano,Smith, & Wurster, 2008), and team leadership during trauma resuscitation (Xiao, Seagull, Mackenzie, & Klein, 2004), to name a few. Whenchoosing to utilize the grounded theory approach, the idea is to select a topic that has been minimally explored.

Steps in Grounded Theory ResearchIn grounded theory research, data are simultaneously collected, coded, and analyzed. This procedure differs from quantitative methods becauseduring the research process, data collection and analysis do not occur sequentially. Rather, in grounded theory, data analysis begins almostimmediately when data collection starts. Grounded theory can utilize a variety of data collection techniques, including interviews, observations,focus groups, historical records, videotapes, diaries, news reports, and any other form of data that is relevant to the research question (Leedy &Ormrod, 2010), although in-depth interviews are the most commonly used method.

One of the most widely used approaches to data analysis in grounded theory is the one suggested by Strauss and Corbin (1990). In thisapproach, data analysis begins by developing categories to classify the data. This process, called open coding, involves the researcher labelingand organizing the data into categories or themes and smaller subcategories that describe the phenomenon being investigated. In this step,initial coding is generally guided by some of the literature review, as well as by topic guides developed by the researcher that direct the codingof themes and categories, based upon the study's research questions. Glaser (1978) suggests three questions to be used in generating andidentifying open codes:

What is this data a study of?

What category does this incident indicate?

What is actually happening in the data?

The next step in data analysis is axial coding, which involves finding connections or relationships between the categories and subcategories(Smith & Davis, 2010). Strauss (1987) indicates that axial coding should involve the examination of antecedent conditions, interactions amongsubjects, strategies, tactics, and consequences. The idea here is to fit together all the pieces, similar to a jigsaw puzzle. Strauss and Corbin(1990) further suggest that axial coding focus on asking the questions Who, When, Where, Why, How, and With what consequences. As newdata are collected, the researcher will move constantly between data collection, open coding, and axial coding to refine the categories. Alsoduring this process, hypotheses are generated and continually tested, based on new data coming in. Data collection and analysis continue untilthe categories are completely saturated. Saturation occurs when no additional supporting or disconfirming data are being found to develop acategory. Thus, saturation occurs when we have learned everything that we can about a category.

The final step, selective coding, involves the researcher combining the categories and their interrelationships into theoretical constructs or a"story line that describes what happens in the phenomenon being studied" (Leedy & Ormrod, 2010, p. 143). In other words, the researcher isintegrating and refining the categories so that the categories can be related to the core categories, or categories that lie at the core of thetheory being generated. It is from this process that theories are generated.

To illustrate the process of grounded theory research, consider an investigation of the active or passive roles played by companions whoaccompany patients to their dental appointments. To examine how these companions affect the interactions between the patient and the dentalprovider, we could begin collecting data using field notes and audio recordings. Next we would compare the interactions among companions,patients, and dentists by assessing their similarities and differences. We would then identify codes from the initial data collected, and developcategories to organize the codes. The following step would be to develop hypotheses about the patterns we observed. Next, we would continueto collect and analyze data for an extended period to test those hypotheses and develop more patterns. We would continue collecting data andrefining hypotheses until we were able to account for and explain all examples (the saturation point). We would then generate a theory fromthe data regarding the roles that companions play when attending dental appointments with patients.

Pros and Cons of Grounded Theory StudiesGrounded theory gives the researcher significant flexibility with respect to the types of data collection methods and the ability to readjust theinvestigation as new data are being collected (Houser, 2009). Grounded theory also provides a thorough analysis of the data, which can lead tofairly solid theories or hypotheses about a particular phenomenon. Additionally, through systematic data collection and analysis procedures, theresearcher is able to explore the complexity of the problem, which often produces richer and more informative results.

Despite the advantages of being able to develop theories from data collected, there are some disadvantages to grounded theory. Probably thebiggest disadvantage involves the difficulty in managing large amounts of data. Since there are no standard guidelines regarding how to identifycategories, the novice researcher may have difficulty developing categories and analyzing the data appropriately. Identifying when a category hasbecome saturated and when a theory has been completely formed can also be difficult and requires some experience. Additionally, groundedtheory research can be very time consuming and tedious.

Case Studies (Qualitative or Descriptive Design)At the 1996 meeting of the American Psychological Association (APA), James Pennebaker— chair of psychology at the University of Texas atAustin—delivered an invited address, describing his research on the benefits of therapeutic writing. Rather than follow the expected route ofshowing graphs and statistical tests to support his arguments, Pennebaker told a story. In the mid-1980s, when Pennebaker's lab was starting tostudy the effects of structured writing on physical and psychological health, one study participant was an American soldier who had served inthe Vietnam War. Like many others, this soldier had had difficulty adjusting to what had happened during the war and consequent troublereintegrating into "normal" civilian life. In Pennebaker's study, he was asked to simply spend 15 minutes per day, over the course of a week,writing about a traumatic experience—in this case, his tour of duty in Vietnam. At the end of this week, as you might expect, this veteran feltawful; these were unpleasant memories that he had not relived in over a decade. But during the next few weeks, amazing things started tohappen. He slept better, he made fewer visits to his doctor, and he even reconnected with his wife after a long separation.

Pennebaker's presentation is an example of a case study that provides a detailed, in-depth analysis of one person over a period of time.Although this case study was collected as part of a larger quantitative experiment, case studies are usually conducted in a therapeutic settingand involve a series of interviews. An interviewer will typically study the subject in detail, recording everything from direct quotes andobservations to his or her own interpretations. We encountered this technique briefly in Chapter 2 (Section 2.1, Overview of Research Designs),in discussing Oliver Sacks's case studies of individuals learning to live with neurological impairments.

Pros and Cons of Case StudiesIn psychology, case studies are a form of qualitative research; thus, they represent the lowest point on our continuum of control. Because theyinvolve one person at a time, without a control group, case studies are often unsystematic. That is, the participants are chosen because they tella compelling story or because they represent an unusual set of circumstances rather than being selected randomly. Studying these individualsallows for a great deal of exploration, which can often inspire future research. However, it is nearly impossible to generalize from one case studyto the larger population. In addition, because the case study includes both direct observation and the researcher's interpretation, there is a riskthat a researcher's biases might influence the interpretations. For example, Pennebaker's investment in demonstrating that writing has healthbenefits could have led to more positive interpretations of the Vietnam veteran's outcomes. However, in this particular case study, Pennebaker'shypothesis about the benefits of writing was supported because his findings mirror those seen in hundreds of controlled experimental studiesthat involved thousands of people. This body of work allows us to feel confident about the conclusions from the single case.

Case studies have two distinct advantages over other forms of research. First is the simple fact that anecdotes are persuasive. DespitePennebaker's nontraditional approach to a scientific talk, the audience came away utterly convinced of the benefits of therapeutic writing. And,despite the fact that Oliver Sacks studied one neurological patient at a time, the stories in his books shed very convincing light on the ability ofhumans to adapt to their circumstances and have a wide appeal to the lay reader. Second, case studies provide a useful way to study rarepopulations and individuals with rare conditions. For example, from a scientific point of view, the ideal might be to gather a random sample ofindividuals living with severe memory impairment due to alcohol abuse and conduct some sort of controlled study in a laboratory environment.This approach could allow us to make causal statements about the results, as we will discuss in Chapter 5 (Section 5.4, Experimental Designs).However, from a practical point of view, this study would be nearly impossible to conduct, making case studies such as Sacks's interviews withWilliam Thompson the best strategy for understanding this condition in depth.

Examples of Case StudiesThroughout the history of psychology, case studies have been used to address a number of important questions and to provide a starting pointfor controlled quantitative studies. For example, in developing his theories of cognitive development, the Swiss psychologist Jean Piaget studiedthe way that his own children developed and changed their thinking styles. Piaget proposed that children would progress through a series offour stages in the way that they approached the world—sensorimotor, preoperational, concrete operational, and formal operational—with eachstage involving more sophisticated cognitive skills than the previous stage. By observing his own children, Piaget noticed preliminary support forthis theory and later was able to conduct more controlled research with larger populations.

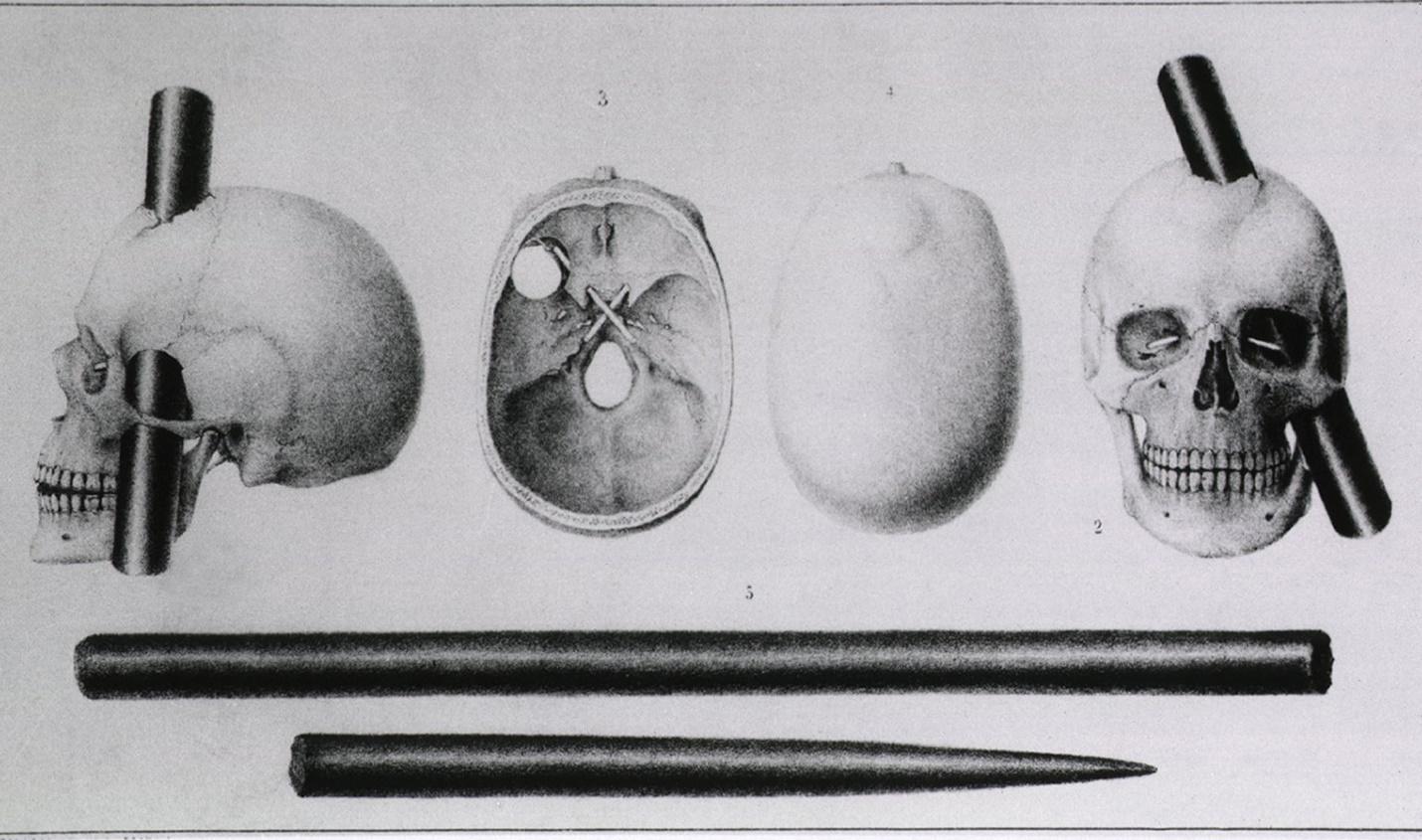

Perhaps one of the most famous case studies in psychology is the story of Phineas Gage, a 19th-century railroad worker who suffered severebrain damage. In September of 1848, Gage was working with a team to blast large sections of rock to make way for new rail lines. After a largehole was drilled into a section of rock, Gage's job was to pack the hole with gunpowder, sand, and a fuse and then tamp it down with a longcylindrical iron rod (known as a "tamping rod"). On this particular occasion, it seems Gage forgot to pack in the sand. So when the iron rodstruck gunpowder, the powder exploded, sending the 3-foot long iron rod through his face, behind his left eye, and out the top of his head.Against all odds, Gage survived this incident with relatively few physical side effects. However, everyone around him noticed that his personalityhad changed—Gage became more impulsive, violent, and argumentative. Gage's physician, John Harlow, reported the details of this case in an1868 article. The following passage is a great example of the rich detail that is often characteristic of case studies:

Courtesy Everett Collection

Various views show an iron rodembedded in Phineas Gage's (1823–1860)skull.

He is fitful, irreverent, indulging at times in the grossest profanity (which was not previously hiscustom), manifesting but little deference for his fellows, impatient of restraint or advice when itconflicts with his desires. A child in his intellectual capacity and manifestations, he has the animalpassions of a strong man. Previous to his injury, although untrained in the schools, he possesseda well-balanced mind, and was looked upon by those who knew him as a shrewd, smartbusinessman, very energetic and persistent in executing all his plans of operation. In this regardhis mind was radically changed, so decidedly that his friends and acquaintances said he was "nolonger Gage." (Harlow, 1868, pp. 339–342)

Gage's transformation ultimately inspired a large body of work in psychology and neuroscience thatattempts to understand the connections between brain areas and personality. The area of his braindestroyed by the tamping rod is known as the frontal lobe, now understood to play a critical role inimpulse control, planning, and other high-level thought processes. Gage's story is a perfect illustration ofthe pros and cons of case studies. On the one hand, it is difficult to determine exactly how much thebrain injury affected his behavior because he is only one person. On the other hand, Gage's tragedyinspired researchers to think about the connections among mind, brain, and personality. As a result, we now have a vast—and still growing—understanding of the brain. This illustrates a key point about case studies: Although individual cases provide limited knowledge about people ingeneral, they often lead researchers to conduct additional work that does lead to generalizable knowledge.

Qualitative Versus Quantitative ApproachesCase studies tend to be qualitative more often than not. The goal of this method is to study a particular case in depth as a way to learn moreabout a rare phenomenon. In both Pennebaker's study of the Vietnam veteran and Harlow's study of Phineas Gage, the researcher approachedthe interview process as a way to gather information and learn from the bottom up about the interviewee's experience. However, it is certainlypossible for a case study to represent quantitative research. This is often the case when researchers conduct a series of case studies, learningfrom the first one of the initial few and then developing hypotheses to test on future cases. For example, a researcher could use the case ofPhineas Gage as a starting point for hypotheses about frontal lobe injury, perhaps predicting that other cases would show similar changes inpersonality. Another way in which case studies can add a quantitative element is for researchers to conduct analyses within a single subject. Forexample, a researcher could study a patient with brain damage for several years following an injury, tracking the association betweendeterioration of brain regions with changes in personality and emotional responses. At the end of the day, though, these examples would stillsuffer from the primary downside of case studies: Because they study a single individual, it is difficult to generalize their findings.

Research: Thinking Critically Acupuncture of Benefit to Those with Unexplained SymptomsBy the Peninsula College of Medicine and Dentistry, Exeter, UK

Attending frequently with medically unexplained symptoms is distressing for both patient and doctor. Inthese settings, effective treatment or management options are limited: One in five patients hassymptoms that remain unexplained by conventional medicine. Studies have shown that the cost to theNational Health Service (NHS, United Kingdom) of managing the treatment of a patient with medicallyunexplained symptoms can be twice that of a patient with a diagnosis.

A research team from the Institute of Health Services Research, Peninsula Medical School, University ofExeter, has carried out a randomised control trial and a linked interview study regarding 80 such patientsfrom GP (General Practitioner) practices across London to investigate their experiences of having five-element acupuncture added to their usual care. This is the first trial of traditional acupuncture forpeople with unexplained symptoms.

The results of the research are published in the British Journal of General Practice. They reveal thatacupuncture had a significant and sustained benefit for these patients and, consequently, acupuncturecould be safely added to the therapies used by practitioners when treating frequently attending patientswith medically unexplained symptoms.

The patient group was made up of 80 adults, 80% female, with an average age of 50 years and from avariety of ethnic backgrounds who had consulted their GP at least eight times in the past year. Nearly60% reported musculoskeletal health problems, of which almost two thirds had been present for a year.

In the 3 months before taking part in the study, the 80 patients had accounted for the following NHSexperiences: 21 patient in-days; 106 outpatient clinic visits; 52 hospital clinic visits (for treatments suchas physiotherapy, chiropody, and counselling); 44 hospital visits for investigations (including 10 magneticresonance imaging [MRI]scans); and 75 visits to non-NHS practitioners such as opticians, dentists, andcomplementary therapists.

The patients were randomly divided into an acupuncture group and a control group. Eight acupuncturistsadministered individual five-element acupuncture to the acupuncture group immediately, up to 12sessions over 26 weeks. The same numbers of treatments were made available to the control groupafter 26 weeks.

At 26 weeks, the patients were asked to complete a number of questionnaires including theindividualized health status questionnaire "Measure Yourself Medical Outcome Profile."

The acupuncture group registered a significantly improved overall score when compared with the controlgroup. They also recorded improved well-being but did not show any change in GP and other clinicalvisits and the number of medications they were taking. Between 26 and 52 weeks, the acupuncturegroup maintained their improvement and the control group, now receiving their acupuncturetreatments, showed a "catch-up" improvement.

The associated qualitative study, which focused on the patients' experiences, supported the quantitativework. This element identified that the participating patients had a variety of long-standing symptomsand disability, including chronic pain, fatigue, and emotional problems, which affected their ability towork, socialize, and carry out everyday tasks. A lack of a convincing diagnosis to explain their symptomsled to frustration, worry, and low mood.

Participating patients reported that their acupuncture consultations became increasingly valuable. Theyappreciated the amount of time they had with each acupuncturist and the interactive and holistic natureof the sessions—there was a sense that the practitioners were listening to their concerns and, viatherapy, doing something positive about them.

As a result, many patients were encouraged to take an active role in their treatment, resulting incognitive and behavioural lifestyle changes, such as a new self-awareness about what caused stress intheir lives, and a subsequent ability to deal with stress more effectively, and taking their own initiativesbased on advice from the acupuncturists about diet, exercise, relaxation, and social activities.

Comments from participating patients included: "The energy is the main thing I have noticed. You know,yeah, it's marvellous! Where I was going out and cutting my grass, now I'm going out and cutting myneighbour's after because he's elderly"; "I had to reduce my medication. That's the big help actually,because medication was giving me more trouble . . . side effects"; and "It kind of boosts you, somehowor another."

Dr. Charlotte Paterson, who managed the randomised control trial and the longitudinal study of patients'experiences, commented: "Our research indicates that the addition of up to 12 five-element acupunctureconsultations to the usual care experienced by the patients in the trial was feasible and acceptable andresulted in improved overall well-being that was sustained for up to a year.

This is the first trial to investigate the effectiveness of acupuncture treatment to those with unexplainedsymptoms, and the next development will be to carry out a cost-effectiveness study with a longer follow-up period. While further studies are required, this particular study suggests that GPs may recommend aseries of five-element acupuncture consultations to patients with unexplained symptoms as a safe andpotentially effective intervention.

Paterson added: "Such intervention could not only result in potential resource savings for the NHS, butwould also improve the quality of life for a group of patients for whom traditional biomedicine has littlein the way of effective diagnosis and treatment."

Peninsula College of Medicine and Dentistry. (2011, May 27). Acupuncture and those with unexplained symptoms. From Paterson, C., Taylor, R.,Griffiths, P., Britten, N., Rugg, S., Bridges, J., McCallum, B., Kite, G. (2011). Acupuncture for 'frequent attenders' with medically unexplainedsymptoms: a randomised controlled trial (CACTUS Study). British Journal of General Practice, Volume 61, Number 587, June 2011 , pp. e295–e305(11) and Rugg, S. , Paterson, C., Britten, N., Bridges, J., Griffiths, P. (2011). Traditional acupuncture for people with medically unexplainedsymptoms: a longitudinal qualitative study of patients' experiences. British Journal of General Practice, Volume 61, Number 587, June 2011 , pp.e306–e315(10).

Think about it:

In this study, researchers interviewed acupuncture patients using open-ended questions and recordedtheir verbal responses, which is a common qualitative research technique. What advantages does thisapproach have over administering a quantitative questionnaire with multiple-choice items?

What are some advantages of adding a qualitative element to a controlled medical trial like this?

What would be some disadvantages of relying exclusively on this approach?

Moving slightly further along the continuum of control, we come to archival research, which involves drawing conclusions by analyzing existingsources of data, including both public and private records. Sociologist David Phillips (1997) hypothesized that media coverage of suicides wouldlead to "copycat" suicides. He tested this hypothesis by gathering archival data from two sources: front-page newspaper articles devoted tohigh-profile suicides and the number of fatalities in the 11-day period following coverage of the suicide. By examining these patterns of data,Phillips found support for his hypothesis. Specifically, fatalities appeared to peak 3 days after coverage of a suicide, and increased publicity wasassociated with a greater peak in fatalities.

Pros and Cons of Archival ResearchIt is difficult to imagine a better way to test Phillips's hypothesis about copycat suicides. You could never randomly assign people to learn aboutsuicides and then wait to see whether they killed themselves. Nor could you interview people right before they committed suicide to determinewhether they were being inspired by media coverage. Archival research provides a way to test the hypothesis by examining existing data andthereby avoids most of the ethical and practical problems of other research designs. Related to this point, archival research also neatly sidestepsissues of participant reactivity, or the tendency of people to behave differently when they are aware of being observed. Any time you conductresearch in a laboratory, participants are aware that they are in a research study and may not behave in a completely natural manner. Incontrast, archival data involve making use of records of people's natural (unstudied) behaviors. The subjects of Phillips's study of copycatsuicides were individuals who decided to kill themselves and who had no awareness that they would be part of a research study.

Archival research is also an excellent strategy for examining trends and changes over time. For example, much of the evidence for globalwarming comes from observing upward trends in recorded temperatures around the globe. To gather this evidence, researchers dig into existingarchives of weather patterns and conduct statistical tests on the changes over time. Psychologists and other social scientists also make use ofthis approach to examine population-level changes in everything from suicide rates to voting patterns over time. These comparisons cansometimes involve a blend of archival and current data. For example, a great deal of social psychology research has been dedicated tounderstanding people's stereotypes about other groups. In a classic series of studies known as the "Princeton Trilogy," researchers documentedthe stereotypes held by Princeton students over several decades (1933 to 1969). Social psychologist Stephanie Madon and her colleagues (2001)collected a new round of data but also conducted a new analysis of this archival data. These new analyses suggested that, over time, peoplehave become more willing to use stereotypes about other groups, even as stereotypes themselves have become less negative.