Students will be required to submit five written assignments in a WORD or pdf document, each 3 pages long, single-spaced, font 12, Times New Roman. A fourth page should list the references cited in

LECTURES 19 & 20 BACK to the FUTURE

| |

In the “history of the world according to salt ” (Lecture 17), animals wore paths to salt licks; men followed; trails became roads, and settlements grew beside them. When the human menu shifted from salt-rich game to cereals (see Lecture 1), more salt was needed to supplement the diet. Since underground deposits were beyond reach, and the salt sprinkled over the surface was insufficient, scarcity kept the mineral (Halite) precious. As civilization spread, salt became one of the world’s principal trading commodities. In these final lectures we will follow the transition in hunter-gatherer societies about ~ 10,000 BC to residential settlements in which Agriculture provided sustenance. The chemical, biochemical and geochemical processes that advanced this evolution will be brought out resulting, eventually, in the Green Revolution of the 20th century in which water management, fertilizers, and pesticides succeeded in alleviating the starvation of millions. The “downsides” of this revolution will be discussed, e.g., nitrogen loading and pollution. Historians also note that the introduction of Agriculture led to the concepts of “labor” and “property” which resulted, in turn, in the stratification of human societies (serfdom, slavery) and warfare.

When did it all start?

James Ussher (1581 – 1656) was, in the Church of Ireland, the Archbishop of Armagh between 1625 and 1656. He was a prolific scholar and church leader, most famous for his identification of the letters of Saint Ignatius of Antioch, and for an amazing piece of scholarship in which he used the Julian calendar to “back track” the chronology in the Bible to establish the time and date of creation in Genesis as "the entrance of the night preceding the 23rd day of October... the year before Christ 4004," that is, ~ 6 pm on October 22, 4004 BC.

Today the theory known as the Big Bang is a cosmological model of the observable universe from the earliest known periods through its subsequent large-scale evolution. The model describes how the universe expanded from an initial state of very high density and temperature, and offers a comprehensive explanation for a broad range of observed phenomena, including the abundance of light elements, cosmic microwave background radiation, the large-scale structure of the Universe, and Hubble's law (the farther away galaxies are, the faster they are moving away from Earth).

If the observed conditions are extrapolated backwards in time using the known laws of physics, the prediction is that just before a period of very high density there was a singularity. See Lecture 13. Based on measurements of the expansion using Type Ia supernovae and measurements of temperature fluctuations in the cosmic microwave background radiation, the time that has passed since that event, known as the "age of the universe, " is 13.799 ± 0.021 billion years.

As noted in Lecture 13, current knowledge is insufficient to determine if anything existed prior to the singularity, the modern version of the hypothetical question posed by Saint Augustine (354-430 AD) in his Confessions, “ What was God doing before he created the Universe? ”

Stellar nucleosynthesis, the process by which elements are created within stars by combining protons and neutrons together from the nuclei of lighter elements, was discussed in Lecture 16. All of the atoms in the universe began as hydrogen. Fusion inside stars transforms hydrogen into helium, heat, and radiation. Heavier elements are created in different types of stars as they die or explode.

The fusion limit is iron (Fe), atomic number 26. Synthesizing heavier elements requires energy. The first pathway involves neutron stars resulting from the collapsed “leftovers” of stars with mass > 8 times the mass of the Sun. In a supernova explosion, the collapsed core of a neutron star creates pressures so great that electrons and protons are forced to merge creating neutrons. In this way, elements up to and including lead (Pb, atomic number 82) are synthesized. That still leaves unexplained elements with atomic number > 82.

Last year, the collision of two neutron stars was observed, something called a kilonova explosion, a rare event occurring only once every 10,000 to 100,000 years.

Black holes of stellar mass are expected to form when very massive neutron stars collapse at the end of their life cycle. The explosion creates a gravitational wave, predicted in 1916 by Einstein in his General Theory of Relativity (see Lecture 16), and confirmed experimentally on September 14, 2015, when LIGO (LIGO stands for “Laser Interferometer Gravitational-wave Observatory’) sensed the predicted undulations in space-time caused by gravitational waves generated by two black holes colliding 1.3 billion light-years away.

In a kilonova explosion, neutrons are scattered in all directions, and existing nuclei absorb neutrons. Neutrons in bombarded nuclei spit out electrons creating protons. More protons means higher atomic numbers and, voilà , we have the whole Periodic Table of Elements and hence all of Chemistry !

What happened after the Big Bang?

According to our current understanding of cosmology, the Universe was featureless and dark for a long stretch of its early history. The first stars did not appear until perhaps 100 million years after the Big Bang, and nearly a billion years passed before galaxies proliferated across the cosmos. How did this dramatic transition from darkness to light come about?

Cosmologists have devised models that show how the density fluctuations left over from the Big Bang could have evolved into the first stars.

The models indicate that the first stars were most likely quite massive and luminous and that their formation was an epochal event that fundamentally changed the Universe and its subsequent evolution. These stars altered the dynamics of the cosmos by heating and ionizing the surrounding gases. The earliest stars also produced and dispersed the first heavy elements, paving the way for the eventual formation of solar systems like our own. And, the collapse of some of the first stars may have seeded the growth of supermassive black holes that formed in the hearts of galaxies and became the spectacular power sources of quasars.

Deductions about the early Universe are based on analyzing the cosmic microwave background radiation which was emitted about 400,000 years after the Big Bang. The uniformity of this radiation indicates that matter was distributed very smoothly at that time. Because there were no large luminous objects to disturb the primordial soup, it must have remained smooth and featureless for millions of years afterward. As the cosmos expanded, the background radiation redshifted to longer wavelengths and the universe grew increasingly cold and dark. Astronomers have no observations of this dark era. But, by a billion years after the Big Bang, some bright galaxies and quasars had already appeared, so the first stars must have formed sometime before.

Although the early universe was remarkably smooth, the background radiation shows evidence of small-scale density fluctuations, clumps in the primordial soup. The cosmological models predict that these clumps would gradually evolve into gravitationally bound structures. Smaller systems would form first and then merge into larger agglomerations. The denser regions would take the form of a network of filaments, and the first star-forming systems, small protogalaxies, would coalesce at the nodes of this network.

Similarly, the cosmological models predict that protogalaxies would then merge to form galaxies, and the galaxies would congregate into galaxy clusters. Although galaxy formation is now mostly complete, galaxies are still assembling into clusters, which are in turn are aggregating into a vast filamentary network that stretches across the universe.

According to the cosmological models, the first small systems capable of forming stars should have appeared between 100 million and 250 million years after the Big Bang. These protogalaxies would have been 100,000 to one million times more massive than the Sun and would have measured about 30 to 100 light-years across. These properties are somewhat similar to those of the molecular gas clouds in which stars are currently being formed in the Milky Way.

The first protogalaxies differed from molecular clouds in fundamental ways. First, they would have consisted mostly of dark matter, elementary particles that are believed to make up about 90 % of the Universe’s mass. In present-day large galaxies, dark matter is segregated from ordinary matter. Over time, ordinary matter concentrates in the galaxy’s inner region, whereas the dark matter remains scattered throughout an enormous outer halo. In protogalaxies, the ordinary matter would still have been mixed with the dark matter.

The second important difference is that the protogalaxies would have contained no significant amounts of any elements besides hydrogen and helium. The Big Bang produced hydrogen and helium, but heavier elements were created later via stellar nucleosynthesis, as described above.

The formation and evolution of the Solar System began ~ 4.5 billion years ago with the gravitational collapse of a small part of a giant molecular cloud. Most of the collapsing mass collected in the center, forming the Sun, while the rest flattened into a protoplanetary disk out of which the planets, moons, asteroids, and other small bodies formed.

How do we know that the Earth formed ~ 4.5 billion years ago?

Whereas the above scenario is based on cosmological models and important assumptions (in particular, the existence of dark matter which, thus far, has not been confirmed experimentally), on this question a more definite answer can be given.

In 1830, the Scottish geologist Charles Lyell, developing ideas put forward by the Scottish natural philosopher James Hutton, popularized the concept that the features of Earth were in perpetual change, eroding and reforming continuously, and the rate of this change was roughly constant.

In 1862, the physicist William Thomson (who later became Lord Kelvin) at the University of Glasgow published calculations that fixed the age of Earth at between 20 million and 400 million years. He assumed that Earth had formed as a completely molten object, and determined the amount of time it would take for the near-surface to cool to its present temperature. His calculations did not account for heat produced via radioactive decay (a process then unknown to science) or convection inside the Earth, which allows more heat to escape from the interior to warm rocks near the surface.

Geologists had trouble accepting such a short age for Earth. Biologists could accept that Earth might have a finite age, but even 400 million years seemed much too short to be plausible. Charles Darwin, who had studied Lyell's work, proposed his theory of evolution of organisms by natural selection, a process whose combination of random heritable variation and cumulative selection implies great expanses of time. Geneticists have subsequently measured the rate of genetic divergence of species, and dated the last, universal ancestor of all living organisms to have lived ~ 3.5-3.8 billion years ago.

Ernest Rutherford and Frederick Soddy, in their work on radioactive materials at McGill University, concluded that radioactivity was due to a spontaneous transmutation of atomic elements. See Lecture 16. In radioactive decay, an element breaks down into another, lighter element, releasing alpha, beta, or gamma radiation in the process. They also determined that a particular isotope of a radioactive element decays into another element at a distinctive rate. This rate is given in terms of a "half life", or the amount of time it takes for half the mass of that radioactive material to break down into its "decay product".

Some radioactive materials have short half-lives; some have long half-lives. Uranium and thorium have long half-lives, and so persist in Earth's crust, but radioactive elements with short half-lives have generally disappeared. This suggested to Rutherford that it might be possible to measure the age of Earth by determining the relative proportions of radioactive materials in geological samples.

A radioactive element does not always decay into one nonradioactive ("stable") element directly, but instead can decay into other radioactive elements that have their own half-lives (and so on) until they reach a stable element. Such "decay series" (e.g., the uranium-radium and thorium series) were known within a few years of the discovery of radioactivity, and provided a basis for constructing techniques of radiometric dating.

Typical radioactive end products are argon from potassium-40 and lead from uranium and thorium decay. If the rock becomes molten, as happens in Earth's mantle, such nonradioactive end products typically escape or are redistributed. Thus the age of the oldest terrestrial rock gives a minimum for the age of Earth assuming that a rock cannot have been in existence for longer than Earth itself. According to radiometric dating and other evidence, Earth formed ~ 4.5 billion years ago.

What has happened over the past 4.5 billion years?

As developed in Lectures 17 and 18, tectonic activity over billions of years, coupled to physical and chemical weathering and chemical erosion led to the landforms we see today.

Earth is the third planet from the Sun and the only astronomical object known to harbor life. According to radiometric dating, Earth formed over 4.5 billion years ago, and studies in genetics have established that the last universal ancestor of all living organisms could be dated 3.5-3.8 billion years ago. Subtraction shows that less than a billion years separated the solidification of the Earth’s crust from the evolution of life on Earth !

The chemistry of the inorganic compounds making up the Earth’s crust was the subject of Lectures 1-4. The chemistry of Carbon and the biochemistry of life was the subject of Lectures 5-8.

The history of agriculture is the story of humankind's development and cultivation of processes for producing food, feed, fiber, fuel, and other goods by the systematic raising of plants and animals. Prior to the development of plant cultivation, human beings were hunters and gatherers. The knowledge and skill of learning to care for the soil and growth of plants advanced the development of human society, allowing clans and tribes to stay in one location generation after generation. Archaeological evidence indicates that such developments occurred ~ 10,000 or more years ago.

Because of agriculture, cities as well as trade relations between different regions and groups of people developed, further enabling the advancement of human societies and cultures. Agriculture has been an important aspect of economics throughout the centuries prior to and after the Industrial Revolution. Sustainable development of world food supplies impact the long-term survival of the species, so care must be taken to ensure that agricultural methods remain in harmony with the environment.

Agriculture is believed to have been developed at multiple times in multiple locations, the earliest of which seems to have been in Southwest Asia in an area referred to as the Fertile Crescent.

Pinpointing the absolute beginnings of agriculture is problematic because the transition away from hunter-gatherer societies in some areas began many thousands of years before the invention of writing. Nonetheless, archaeobotanists and paleoethnobotanists have traced the selection and cultivation of specific food plant characteristics, such as a semi-tough rachis and larger seeds, to just after ~ 9,500 BC in the early Holocene period in the Levant region of the Fertile Crescent.

There is evidence for the earlier use of wild cereals. Anthropological and archaeological evidence from sites across Southwest Asia and North Africa indicate use of wild grain (from the ~ 20,000 BC site of Ohalo II in Israel, many Natufian sites in the Levant and from sites along the Nile in the 10th millennium BC.).

There is even early evidence for planned cultivation and trait selection: grains of rye with domestic traits have been recovered from ~ 10,000 BC sites at Abu Hureyra in Syria, but this appears to be a localized phenomenon resulting from cultivation of stands of wild rye, rather than a definitive step towards domestication. It isn't until after ~ 9,500 BC that the eight so-called foundation crops of agriculture appear: first emmer and einkorn wheat (see Lecture 1), then hulled barley, peas, lentils, bitter vetch, chick peas, and flax. These eight crops occur more or less simultaneously on Pre-Pottery Neolithic sites in the Levant, although the consensus is that wheat was the first to be sown and harvested on a significant scale.

By ~ 7000 BC, sowing and harvesting reached the Levant and there, in the super fertile soil just north of the Persian Gulf, Sumerian ingenuity systematized and scaled it up. By ~ 6000 BC, farming was entrenched on the banks of the Nile River.

About this time, agriculture was developed independently in the Far East, probably in China, with rice rather than wheat as the primary crop. Maize was first domesticated, probably from native teosinte, in the Americas around 3000-2700 BC, though there is some archaeological evidence of a much earlier development. The potato, the tomato, the pepper, squash, several varieties of bean, and several other plants were also developed in the New World, as was quite extensive terracing of steep hillsides in much of Andean South America.

Agriculture was also independently developed on the island of New Guinea.

The reasons for the development of farming may have included climate change, but possibly there were also social reasons (such as accumulation of food surplus for competitive gift-giving (as in the Pacific Northwest potlatch culture). Most certainly, there was a gradual transition from hunter-gatherer to agricultural economies after a lengthy period during which some crops were deliberately planted and other foods were gathered in the wild. Although localized climate change is the favored explanation for the origins of agriculture in the Levant, the fact that farming was “invented” at least three times elsewhere, and possibly more, suggests that social reasons may have been instrumental.

Full dependency on domestic crops and animals did not occur until the Bronze Age (3000–1200 BC ) by which time wild resources contributed a nutritionally insignificant component to the usual diet. If the operative definition of agriculture includes large scale intensive cultivation of land, mono-cropping, organized irrigation, and use of a specialized labor force, the title "inventors of agriculture" would fall to the Sumerians, starting around ~ 5,500 BC.

Intensive farming allows a much greater population density than can be supported by hunting and gathering, and allows for the accumulation of excess product for off-season use, or to sell or barter. The ability of farmers to feed large numbers of people whose activities have nothing to do with material production was the crucial factor in the rise of division of labor, the sense of property and standing armies.

Agriculture of the Sumerians supported a substantial territorial expansion, together with much internecine conflict between cities, making them the first empire builders. Not long after, the Egyptians, powered by farming in the fertile Nile valley, achieved a population density from which enough warriors could be drawn for a territorial expansion, more than tripling the Sumerian empire in area.

ANCIENT AGRICULTURE

SUMERIEN AGRICULTURE

In Sumer (the area that later became Babylonia and is now southern Iraq, from around Baghdad to the Persian Gulf), barley was the main crop, but wheat, flax, dates, apples, plums, and grapes were grown as well. While Mesopotamia was blessed with flooding from the Tigris and Euphrates rivers that helped cultivate plant life, salt deposits under the soil, made it hard to farm. The earliest known sheep and goats were domesticated in Sumer and were in a much larger quantity than cattle. Sheep were kept mainly for meat and milk, and butter and cheese were made from the latter. Ur, a large town that covered about 50 acres, had 10,000 animals kept in sheepfolds and stables and 3,000 slaughtered every year. The city's population of 6,000 included a labor force of 2,500 cultivating 3,000 acres of land. The labor force contained storehouse recorders, work foremen, overseers, and harvest supervisors to supplement laborers. Agricultural produce was given to the Gala, priests of the Sumerian goddess Inanna, important people in the community. Shown below is a Sumerian harvester’s sickle made of baked clay, ~ 3000 BC, in the Field Museum.

The land was plowed by teams of oxen pulling light plows w/o wheels and grain was harvested with sickles. Wagons had solid wheels covered by leather tires kept in position by copper nails and were drawn by oxen and the Syrian onager (now extinct). Animals were harnessed by collars, yokes, and head stalls. They were controlled by reins, and a ring through the nose or upper lip and a strap under the jaw. As many as four animals could pull a wagon at one time. Though some hypothesize that domestication of the horse occurred as early as ~ 4000 BC in the Ukraine, the horse was definitely in use by the Sumerians around ~ 2000 BC.

AZTEC and MAYA AGRICULTURE

Agriculture in Mesoamerica dates to the Archaic period of Mesoamerican chronology (8000-2000 BC). During this period, many of the hunter gatherer bands in the region began to cultivate wild plants. The cultivation of these plants probably started out as creating “fall back, “ or starvation foods, near seasonal camps, that the band could rely on when hunting was bad, or when there was a drought.

By creating these known areas of plant food, it would have been easier for the band to be in the right place, at the right time, to collect them. Eventually, a subsistence pattern, based on plant cultivation, supplemented with small game hunting, became much more reliable, efficient, and generated a larger yield.

As cultivation became more focused, many plant species became domesticated. These plants were no longer able to reproduce on their own, and many of their physical traits were modified by human farmers. The most famous of these, and the most important to Mesoamerican agriculture, is maize. Maize is storable for long periods of time, it can be ground into flour, and it easily turns into surplus for future use. Maize became vital to the survival of the people of Mesoamerica, and that is reflected in their origin, myths, artwork, and rituals.

The second most important crop in Mesoamerican agriculture is the squash. Cultivated and domesticated before maize, dated to ~ 8000 BC in Oaxaca, the people of Mesoamerica utilized several different types of squash. The most important may be the pumpkin, and its relatives. The seeds of the pumpkin are full of protein, and are easily transportable. Another important member of the squash family is the bottle gourd. This fruit may not have been very important as a food source, but the gourd itself would have been useful as a water container.

Another major food source in Mesoamerica are beans. These may have been used as early as squash and maize, but the exact date of domestication is not known. These three crops formed the center of Mesoamerican agriculture. Maize, beans, and squash form a triad of products, commonly referred to as the "Three Sisters," that provided the people of Mesoamerica a complementing nutrient triangle. Each contributes some part of the essential vitamin mix that human beings need to survive. An additional benefit to these three crops is that planting them together helps to retain nutrients in the soil.

Many other plants were first cultivated in Mesoamerica. tomatoes, avocados, guavas, chili peppers, manioc, agave, and prickly pear were all cultivated as additional food resources, while rubber trees and cotton plants were useful for making cultural products like latex balls and clothing. Another culturally important plant was the cacao. Cacao beans were used as money, and later, the beans were used for making another valuable product, chocolate.

The Aztecs were some of the most innovative farmers of the ancient world, and farming provided the entire basis of their economy. The land around Lake Texcoco was fertile but not large enough to produce the amount of food needed for the population of their expanding empire. The Aztecs developed irrigation systems, formed terraced hillsides, and fertilized their soil.

However, their greatest agricultural technique was the chinampa or artificial islands also known as "floating gardens." These were used to make the swampy areas around the lake suitable for farming. To make chinampas, canals were dug through the marshy islands and shores, then mud was heaped on huge mats made of woven reeds. The mats were anchored by tying them to posts driven into the lake bed and then planting trees at their corners that took root and secured the artificial islands permanently. The Aztecs grew corn, squash, vegetables, and flowers on chinampas.

ROMAN AGRICULTURE

A gallic-roman harvester from a Wall in Buzenol, Belgium

Roman agriculture was highly regarded in Roman culture, built on techniques pioneered by the Sumerians, with a specific emphasis on the cultivation of crops for trade and export. Romans laid the groundwork for the manorial economic system involving serfdom, which flourished in the Middle Ages.

By the fifth century Greece had started using crop rotation methods and had large estates while farms in Rome were small and family owned. Rome’s contact with Carthage, Greece, and the Hellenistic East in the third and second centuries improved Rome’s agricultural methods. Roman agriculture reached its height of productivity and efficiency during the late republic and early empire.

There was a significant amount of commerce between the provinces of the empire. All the regions of the empire became interdependent with one another, some provinces specialized in the production of grain, others in wine and others in olive oil, depending on the soil type. The Po Valley (northern Italy) became a haven for cereal production, the province of Etruria had heavy soil good for wheat, and the volcanic soil in Campania made it well-suited for wine production.

In addition to knowledge of different soil categories, the Romans also took interest in what type of manure was best for the soil. The best was poultry manure, and cow manure one of the worst. Sheep and goat manure were also good. Donkey manure was best for immediate use, while horse manure was not good for grain crops, but it was very good for meadows because "it promoted a heavy growth of grass." Some crops grown on Roman farms include wheat, barley, millet, kidney bean, pea, broad bean, lentil, flax, sesame, chickpea, hemp, turnip, olive, pear, apple, fig, and plum.

The Romans also used animals extensively. Cows provided milk while oxen and mules did the heavy work on the farm. Sheep and goats were cheese producers, but were prized even more for their hides. Horses were not important to Roman farmers; most were raised by the rich for racing or war. Sugar production centered on beekeeping. Some Romans raised snails as luxury items.

Roman law placed high priorities on agriculture since it was the livelihood of the people in early Rome. A Roman farmer had a legal right to protect his property from unauthorized entry and could even use force to do so. The Twelve Tables lists destroying someone else's crop as punishable by death. Burning a heap of corn was also a capital offense. The vast majority of Romans were not wealthy farmers with vast estates farmed for a profit. Since the average farm family size was 3.2 persons, ownership of animals and size of land determined production quantities, and often there was little surplus of crops.

CHINESE AGRICULTURE

The unique tradition of Chinese agriculture has been traced to the pre-historic Yangshao culture, about ~ 5000-3000 BC, and Longshan culture 3000-2000 BC. Chinese historical and governmental records of the Warring States (481-221 BC), Qin Dynasty (221-207 BC), and Han Dynasty (202 BC - 220 AD ) eras allude to the use of complex agricultural practices, such as a nationwide granary system and widespread use of silkworms for producing silk. The oldest Chinese book on agriculture is the Chimin Yaoshu of 535 AD, written by Jia Sixia. Terraced rice fields in Yunnan province are shown below.

For agricultural purposes, the Chinese had innovated the hydraulic-powered trip hammer by the first century BC. Although it found other purposes, its main function was to pound, decorticate, and polish grain, tasks that otherwise would have been done manually. The Chinese also innovated the square-pallet chain pump by the first century AD, powered by a waterwheel or an oxen pulling a system of mechanical wheels. Although the chain pump found use in public works of providing water for urban and palatial pipe systems, it was used mainly to lift water from a lower to higher elevation in filling irrigation canals and channels for farmland.

During the Eastern Jin (317-420) and the Northern and Southern Dynasties (420-589), the Silk Road and other international trade further spread farming technology throughout China. Political stability and a growing labor force led to economic growth, and people opened up large areas of wasteland and built irrigation works for expanded agricultural use. As land use became more intensive and efficient, rice was grown twice a year and cattle began to be used for plowing and fertilization. By the Tang Dynasty (618-907), China had become a unified feudal agricultural society. Improvements in farming machinery during this era included the moldboard plow and watermill. Later during the Yuan Dynasty (1271-1368), cotton planting and weaving technology were extensively adopted and improved.

INDIAN AGRICULTURE

Evidence of the presence of wheat and some legumes in the sixth millennium BC have been found in the Indus Valley. Oranges were cultivated in the same millennium. The crops grown in the valley around were typically wheat, peas, sesame seed, barley, dates, and mangoes. By 3500 BC cotton growing and cotton textiles were quite advanced in the valley. By 3000 BC farming of rice had started. Another monsoon crop of importance at that time was cane sugar. By 2500 BC, rice was an important component of the staple diet in Mohenjodaro near the Arabian Sea. A paddy field in South India is shown below.

The Indus Plain had rich alluvial deposits which came down the Indus River in annual floods. This helped sustain farming that formed basis of the Indus Valley Civilization at Harappa. The people built dams and drainage systems for the crops.

By 2000 BC tea, bananas, and apples were being cultivated in India. There was coconut trade with East Africa in 200 BC . By 500 AD eggplants were being cultivated.

AGRICULTURE in the MIDDLE AGES

The Middle Ages owe much of its development to advances made in Islamic countries, which flourished culturally and materially. Europe and other Roman and Byzantine administered lands entered an extended period of social and economic stagnation. This was in great part due to the fact that serfdom became widespread in eastern Europe in the Middle Ages.

As early as the ninth century, an essentially modern agricultural system became central to economic life and organization in the Arab caliphates, replacing the largely export-driven Roman model. The great cities of the Near East, North Africa and Moorish Spain were supported by elaborate agricultural systems which included extensive irrigation based on knowledge of hydraulic and hydrostatic principles, some of which were continued from Roman times. In later centuries, Persian Muslims began to function as a conduit, transmitting cultural elements, including advanced agricultural techniques, into Turkic lands and western India. The Muslims introduced what was to become an agricultural revolution based on the following factors:

Development of a sophisticated system of irrigation using machines such as norias (newly invented water raising machines), dams and reservoirs. With such technology they managed to greatly expand the exploitable land area.

The adoption of a scientific approach to farming enabled them to improve farming techniques derived from the collection and collation of relevant information throughout the whole of the known world. Farming manuals were produced in every corner of the Muslim world detailing where, when and how to plant and grow various crops. Advanced scientific techniques allowed the introduction of new crops and breeds and strains of livestock into areas where they were previously unknown.

Incentives based on a new approach to land ownership and laborers' rights, combining the recognition of private ownership and the rewarding of cultivators with a harvest share commensurate with their efforts. Their counterparts in Europe struggled under a feudal system in which they were almost slaves (serfs) with little hope of improving their lot by hard work.

The introduction of new crops transformed private farming into a new global industry exported everywhere including Europe, where farming was mostly restricted to wheat strains obtained much earlier via central Asia. Spain received what she in turn transmitted to the rest of Europe. Many agricultural and fruit-growing processes, together with many new plants, fruit and vegetables. These new crops included sugar cane, rice, citrus fruit, apricots, cotton, artichokes, aubergines, and saffron. Others, previously known, were further developed. Muslims also brought to that country almonds, figs, and sub-tropical crops such as bananas. Several were later exported from Spanish coastal areas to the Spanish colonies in the New World. Via Muslim influence, a silk industry flourished, flax was cultivated and linen exported, and esparto grass, which grew wild in the more aridparts, was collected and turned into various articles.

RENAISSANCE to INDUSTRIAL REVOLUTION

The invention of a three-field system of crop rotation during the Middle Ages, and the importation of the Chinese-invented moldboard plow, vastly improved agricultural efficiency. After 1492 the world's agricultural patterns were shuffled in the widespread exchange of plants and animals known as the Columbian Exchange. Crops and animals that were previously only known in the Old World were now transplanted to the New World and vice versa. Perhaps most notably, the tomato became a favorite in European cuisine, and maize and potatoes were widely adopted. Other transplanted crops include pineapple, cocoa, and tobacco. In the other direction, several wheat strains quickly took to western hemisphere soils and became a dietary staple even for native North, Central, and South Americans.

Agriculture was a key element in the Atlantic slave trade. Slaves, like land, were regarded as property. In the expanding Plantation economy, large plantations produced crops including sugar, cotton, and indigo that were heavily dependent upon slave labor.

By the early 1800s, agricultural practices, particularly careful selection of hardy strains and cultivators, had so improved that yield per land unit was many times that seen in the Middle Ages and before, especially in the largely virgin soils of North and South America. The eighteenth and nineteenth century also saw the development of glass houses or greenhouses, initially for the protection and cultivation of exotic plants imported to Europe and North America from the tropics. Experiments on plant hybridization in the late 1800s yielded advances in the understanding of plant genetics, and subsequently, the development of hybrid crops. Storage silos and grain elevators appeared in the nineteenth century.

Increasing dependence upon monoculture crops lead to famines and food shortages, most notably the Irish Potato Famine (1845–1849).

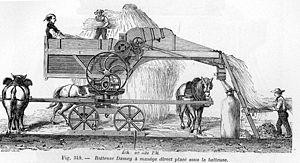

The birth of industrial agriculture more or less coincides with that of the Industrial Revolution. With the rapid rise of mechanization in the late nineteenth and twentieth centuries, particularly in the form of the tractor, farming tasks could be done with a speed and on a scale previously impossible. Compare the following.

These advances, joined with science-driven innovations in methods and resources, have led to efficiencies enabling modern farms in the United States, Argentina, Israel, Germany and a few other nations to output volumes of high quality produce per land unit at what may be the practical limit. The development of rail and highway networks and the increasing use of container shipping and refrigeration in developed nations have also been essential to the growth of mechanized agriculture, allowing for the economical long distance shipping of produce.

The identification of nitrogen and phosphorus as critical factors in plant growth led to the manufacture of synthetic fertilizers, making possible more intensive types of agriculture. The discovery of vitamins and their role in animal nutrition in the first two decades of the twentieth century, led to vitamin supplements, which in the 1920s allowed certain livestock to be raised indoors, reducing their exposure to adverse natural elements. The discovery of antibiotics and vaccines (see Lecture 12) facilitated raising livestock in larger numbers by reducing disease. Chemicals developed for use in World War II gave rise to synthetic pesticides. Other applications of scientific research since 1950 in agriculture include gene manipulation, and hydroponics.

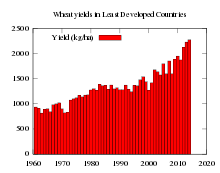

Agricultural production across the world doubled four times between 1820 and 1975. It doubled between 1820 and 1920; between 1920 and 1950; between 1950 and 1965; and again between 1965 and 1975, so as to feed a global population of one billion human beings in 1800 and 6.5 billion in 2002.

During the same period, the number of people involved in farming dropped as the process became more automated. In the 1930s, 24 percent of the American population worked in agriculture compared to 1.5 percent in 2002. In 1940, each farm worker supplied 11 consumers, whereas in 2002, each worker supplied 90 consumers. The number of farms has also decreased, and their ownership is more concentrated.

In the U.S., four companies kill 81 percent of cows, 73 percent of sheep, 57 percent of pigs, and produce 50 percent of chickens, cited as an example of "vertical integration" by the president of the U.S. National Farmers' Union. In 1967, there were one million pig farms in America; as of 2002, there were 114,000, with 80 million pigs (out of 95 million) killed each year on factory farms, according to the U.S. National Pork Producers Council. According to the Worldwatch Institute, 74 % of the world's poultry, 43 % of beef, and 68 % of eggs are produced this way.

GREEN REVOLUTION

The Green Revolution was the notable increase in cereal-grains production in Mexico, India, Pakistan, the Philippines, and other developing countries in the 1960s and 1970s. This trend resulted from the introduction of hybrid strains of wheat, rice, and corn (maize) and the adoption of modern agricultural technologies, including irrigation and heavy doses of chemical fertilizer.

The Green Revolution was launched by research establishments in Mexico and the Philippines that were funded by the governments of those nations, international donor organizations, and the U.S. government. Similar work is still being carried out by a network of institutes around the world.

The Green Revolution was based on years of painstaking scientific research, but when it was deployed in the field, it yielded dramatic results, nearly doubling wheat production in a few years. The extra food produced by the Green Revolution is generally considered to have averted famine in India and Pakistan. It also allowed many developing countries to keep up with the population growth that many observers had expected would outstrip food production. The leader of a Mexican research term, U.S. agronomist Norman Borlaug, was instrumental in introducing the new wheat to India and Pakistan and was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 1970.

Norman Borlaug (1914 -2009) was an American agronomist born in Cresco, Iowa, who led initiatives worldwide that contributed to the extensive increases in agricultural production termed the Green Revolution. He was hired in 1944 to run a wheat-research program established by the Rockefeller Foundation and the government of Mexico in an effort to make that country self-sufficient in the production and distribution of cereal grains. Borlaug's team developed varieties of wheat that grew well in various climatic conditions and benefited from heavy doses of chemical fertilizer, more so than the traditional plant varieties. Wheat yield per acre rose fourfold from 1944 to 1970. Mexico, which had previously had to import wheat, became a self-sufficient cereal-grain producer by 1956.

The key breakthrough in Mexico was the breeding of short-stemmed wheat that grew to lesser heights than other varieties. Whereas tall plants tend both to shade their neighbors from sunlight and topple over before harvesting, uniformly short stalks grow more evenly and are easier to harvest. The Mexican dwarf wheat was first released to farmers in 1961 and resulted in a doubling of the average yield. Borlaug described the twenty years from 1944 to 1964 as the "silent revolution" that set the stage for the more dramatic Green Revolution to follow.

In the 1960s, many observers felt that widespread famine was inevitable in the developing world and that the population would surpass the means of food production, with disastrous results in countries such as India. The United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization calculated that 56 % of the human race lived in countries with an average per-capita food supply of 2,200 calories per day or less, which is barely at subsistence level.

Biologist Paul Ehrlich predicted in his 1968 bestseller The Population Bomb that "hundreds of millions" would starve to death in the 1970s and 1980s "in spite of any crash programs embarked upon" at the time he wrote his book.

In 1963, just such a devastating famine had threatened India and Pakistan. Borlaug went to the subcontinent to try to persuade governments to import the new varieties of wheat. Not until 1965 was Borlaug able to overcome resistance to the relatively unfamiliar crop and its foreign seeds and bring in hundreds of tons of seed to jump-start production.

The new plants caught on rapidly. By the 1969–1970 crop season, about the time Ehrlich was dismissing "crash programs," 55 % of the 35 million acres of wheat in Pakistan and 35 % of India's 35 million acres of wheat were sown with the Mexican dwarf varieties or varieties derived from them.

New production technologies were also introduced, such as a greater reliance on chemical fertilizer and pesticides and the drilling of thousands of wells for controlled irrigation. Government policies that encouraged these new styles of production provided loans that helped farmers adopt it.

Wheat production in Pakistan nearly doubled in five years, going from 4.6 million tons in 1965 (a record at the time) to 8.4 million tons in 1970. India went from 12.3 million tons of wheat in 1965 to 20 million tons in 1970. Both nations were self-sufficient in cereal production by 1974.

As important as the wheat program was, however, rice remains the world's most important food crop, providing 35–80 % of the calories consumed by people in Asia. The International Rice Research Institute in the Philippines was founded in 1960 and was funded by the Ford and Rockefeller Foundations, the government of the Philippines, and the U.S. Agency for International Development. This organization was to do for rice what the Mexican program had done for wheat.

Scientists addressed the problem of intermittent flooding of rice paddies by developing strains of rice that would thrive even when submerged in three feet of water. The new varieties produced five times as much rice as the traditional deepwater varieties and opened flood-prone land to rice cultivation. Other varieties were dwarf (for the same reasons as the wheat), or more disease-resistant, or more suited to tropical climates. Scientists crossed thirty-eight different breeds of rice to create IR8, which doubled yields and became known as "miracle rice."

IR8 served as the catalyst for what became known as the Green Revolution. By the end of the twentieth century, more than 60 % of the world's rice fields were planted with varieties developed by research institutes and related developers. A pest-resistant variety known as IR36 was planted on nearly 28 million acres, a record amount for a single food-plant variety.

In addition to Mexico, Pakistan, India, and the Philippines, countries benefiting from the Green Revolution included Afghanistan, Sri Lanka, China, Indonesia, Iran, Kenya, Malaya, Morocco, Thailand, Tunisia, and Turkey. The Green Revolution contributed to the overall economic growth of these nations by increasing the incomes of farmers (who were then able to afford tractors and other modern equipment), the use of electrical energy, and consumer goods, thus increasing the pace and volume of trade and commerce.

As successful as the Green Revolution was, the wholesale transfer of technology to the developing world had its critics. Some objected to the use of chemical fertilizer, which augmented or replaced animal manure or mineral fertilizer. Others objected to the use of pesticides, some of which are believed to be persistent in the environment. The use of irrigation was also criticized, as it often required drilling wells and tapping underground water sources, as was the encouragement of farming in areas formerly considered marginal, such as flood-prone regions in Bangladesh.

The very fact that the new crop varieties were developed with foreign support caused some critics to label the entire program imperialistic. Critics also argued that the Green Revolution primarily benefited large farm operations that could more easily obtain fertilizer, pesticides, and modern equipment, and that it helped displace poorer farmers from the land, driving them into urban slums. Critics also pointed out that the heavy use of fertilizer and irrigation causes long-term degradation of the soil.

Proponents of the Green Revolution argued that it contributed to environmental preservation because it improved the productivity of land already in agricultural production and thus saved millions of acres that would otherwise have been put into agricultural use. It is estimated that if cropland productivity had not tripled in the second half of the twentieth century, it would have been necessary to clear half of the world's remaining forest-land for conversion to agriculture.

However, the rates at which production increased in the early years of the program could not continue indefinitely, which caused some to question the "sustainability" of the new style. For example, rice yields per acre in South Korea grew nearly 60% from 1961 to 1977, but only 1% from 1977 to 2000.

Rice production in Asia as a whole grew an average of 3.2% per year from 1967 to 1984 but only 1.5 % per year from 1984 to 1996. Some of the leveling-off of yields stemmed from natural limits on plant growth, but economics also played a role. For example, as rice harvests increased, prices fell, thus discouraging more aggressive production. Also, population growth in Asia slowed, thus reducing the rate of growth of the demand for rice. In addition, incomes rose, which prompted people to eat less rice and more of other types of food.

See More

The success of the Green Revolution also depended on the fact that many of the host countries, such as Mexico, India, Pakistan, the Philippines, and China, had relatively stable governments and fairly well-developed infrastructures. These factors permitted these countries to diffuse both the new seeds and technology and to bring the products to market in an effective manner.

The challenges were far more difficult in places such as Africa, where governments were unstable and roads and water resources were less developed. For example, in mid-1990s Mozambique, improved corn grew well in the northern part of the country, but civil unrest and an inadequate transportation system left much of the harvest to rot. With the exception of a few countries such as Kenya, where corn yields quadrupled in the 1970s, Africa benefited far less from the Green Revolution than Asian countries and is still threatened periodically with famine.

The Green Revolution could not have been launched without the scientific work done at the research institutes in Mexico and the Philippines. The two original institutes have given rise to an international network of research establishments dedicated to agricultural improvement, technology transfer, and the development of agricultural resources, including trained personnel, in the developing countries. A total of sixteen autonomous centers form the Consultative Group on International Agricultural Research (CGIAR), which operates under the direction of the World Bank. These centers address issues concerning tropical agriculture, dry-area farming, corn, potatoes, wheat, rice, livestock, forestry, and aquatic resources, among others.

Future advances in agricultural productivity depend on the development of new varieties of plants such as sorghum and millet, which are mainstays in African countries and other less-developed areas, and on the introduction of appropriate agricultural technology.

This will probably include biotechnology and genetic engineering, the genetic alteration of food plants to give them desirable characteristics. See Lecture 12. For example, farmers in Africa are plagued by hardy, invasive weeds that can quickly overrun a cultivated plot and compel the farmer to abandon it and move on to virgin land. If the plot were planted with corn, soybeans, or other crops that are genetically altered to resist herbicide, then the farmer could more easily control the weeds and harvest a successful crop.

Scientists are also developing a genetically modified strain of rice fortified with vitamin A that is intended to help ward off blindness in children, which will be especially useful in developing countries. While people have expressed concern about the environmental impact of genetically modified food plants, such plants are well established in the United States and some other countries and are likely to catch on in the developing world as well.

In the above, the use of fertilizers and pesticides was noted. Fertilizers were

discussed at length in Lecture 18. Following are short descriptors of pesticides and herbicides.

Pesticides are substances that are meant to control pests, including weeds. The term pesticide includes all of the following: herbicide and insecticides, which may include insect growth regulators.

The most common of these are herbicides which account for approximately 80% of all pesticide use. Most pesticides are intended to serve as plant protection products, which protect plants from weeds, fungi, or insects.

The World’s 10 Largest Fertilizer Companies.

BASF.

Uralkali PJSC.

Israel Chemicals.

Yara International.

Potash Corporation of Saskatchewan.

The Mosaic Company.

Agrium.

The World’s Top 6 Pesticide Companies

The "Big 6" pesticide and GMO corporations are BASF, Bayer, Dupont, Dow Chemical Company, Monsanto, and Syngenta. They are so called because they dominate the agricultural input market, that is, they own the world’s seed, pesticide and biotechnology industries.

According to the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD), corporate concentration of the agricultural input market "has far-reaching implications for global food security, as the privatization and patenting of agricultural innovation (gene traits, transformation technologies and seed germplasm) has been supplanting traditional agricultural understandings of seed, farmers' rights, and breeders' rights."

The World's Top 10 Seed Companies

| Company – 2007 | Seed sales (US$ millions) | % of global proprietary seed market |

| Monsanto (US) | $4,964m | 23% |

| DuPont (US) | $3,300m | 15% |

| Syngenta (Switzerland) | $2,018m | 9% |

| Groupe Limagrain (France) | $1,226m | 6% |

| Land O' Lakes (US) | $917m | 4% |

| KWS AG (Germany) | $702m | 3% |

| Bayer Crop Science (Germany) | $524m | 2% |

| Sakata (Japan) | $396m | <2% |

| DLF-Trifolium (Denmark) | $391m | <2% |

| Takii (Japan) | $347m | <2% |

| Top 10 Total | $14,785m | 67% [of global proprietary seed market] |

These 10 companies control the price of the food you buy.

The effects of the Green Revolution on global food security are difficult to assess because of the complexities involved in food systems.

The world population has grown by about five billion since the beginning of the Green Revolution and many believe that, without the Revolution, there would have been greater famine and malnutrition.

India saw annual wheat production rise from 10 million tons in the 1960s to 73 million in 2006. The average person in the developing world consumes roughly 25% more calories per day now than before the Green Revolution. Between 1950 and 1984, as the Green Revolution transformed agriculture around the globe, world grain production increased by about 160%.

The production increases fostered by the Green Revolution are often credited with having helped to avoid widespread famine, and for feeding billions of people.

There are also concerns that the Green Revolution has decreased food security for a large number of people. One concern involves the shift of subsistence-oriented cropland to cropland oriented towards production of grain for export or animal feed. For example, the Green Revolution replaced much of the land used for pulses (see below) that fed Indian peasants for wheat, which did not make up a large portion of the peasant diet.

baked beans

red, green, yellow and brown lentils

chickpeas (chana or garbanzo beans)

garden peas

black-eyed peas

runner beans

broad beans (fava beans)

kidney beans, butter beans (Lima beans), haricots, cannellini beans, flageolet beans, pinto beans and borlotti beans

The spread of Green Revolution agriculture affected both agricultural biodiversity and wild biodiversity. There is little disagreement that the Green Revolution acted to reduce agricultural biodiversity, as it relied on just a few high-yield varieties of each crop.

This has led to concerns about the susceptibility of a food supply to pathogens that cannot be controlled by agrochemicals, as well as the permanent loss of many valuable genetic traits bred into traditional varieties over thousands of years.

Nikolai Vavilov (1887-1943) was a prominent Russian agronomist best known for having identified the centers of origin of cultivated plants. He devoted his life to the study and improvement of wheat, corn, and other cereal crops that sustain the global population.

While developing his theory on the centers of origin of cultivated plants, Vavilov organized a series of botanical-agronomic expeditions, and collected seeds from every corner of the globe. In Leningrad (St. Petersburg), he established a seed bank, to preserve genetic varieties of plant seeds.

After the Nazis invaded the Soviet Union in the Summer of 1941, beginning in September, a German army surrounded the city of Leningrad in an extended siege. The 872 days of the siege caused extreme famine in the Leningrad region through disruption of utilities, water-, energy- and food-supplies.

Civilians in the city suffered extreme starvation, especially in the Winter of 1941–42. From November 1941 to February 1942 the only food available to a citizen was 125 grams of bread per day, of which 50–60% consisted of sawdust and other inedible admixtures. In conditions of extreme temperatures (down to −22 °F ), and with city transport out of service, even a distance less than mile to a food distributing kiosk created an insurmountable obstacle for many citizens. Deaths peaked in January–February 1942 at 100,000 per month, mostly from starvation. In total, the siege of Leningrad resulted in the death of an estimated 800,000 civilians, nearly as many as ALL the World War II deaths of the United States and the United Kingdom combined. Overall, the siege resulted overall in the death of ~one million people.

Several years ago, I was awarded an honorary doctorate ( honoris causa) from the National Slovak Agricultural University in Nitra, Slovakia. The other recipient was Professor Dr. Viktor Dragavcev, the Director of the Plant Research Institute of N. I. Vavilov. He told me the following.

During World War II’s 28-month-long siege of Leningrad, several workers charged with caring for the Institute’s collection faced an unthinkable choice. In preparation for Germany’s civilian attack, all art was vacated from the Hermitage, but Soviet officials neglected to account for a different, equally invaluable collection, seeds curated by the Vavilov Institute. The collection at that time was, and probably still is, the largest collection of seeds in the world.

With the Institute’s namesake Vavilov imprisoned by Stalin in a gulag (where he would die of starvation in 1943 before the war’s end), scientists working at the Institute took matters into their own hands. Amongst themselves, they agreed to rotate shifts at guard, protecting the seeds from threats ranging from intruders to rats to their own hunger. By the end of the infamously brutal campaign, many of these botanists lost their lives protecting the collection, nine of whom starved to death while literally surrounded by food in various states of growth.

Even in the midst of a World War, with society crumbling on all sides, saving themselves would have come at the expense of the very safety net they’d been building as a gift for the post-apocalyptic world and all of humanity.

There are varying opinions about the effect of the Green Revolution on wild biodiversity. One hypothesis speculates that by increasing production per unit of land area, agriculture will not need to expand into new, uncultivated areas to feed a growing human population. However, land degradation and soil nutrients depletion have forced farmers to clear up formerly forested areas in order to keep up with production.

A counter-hypothesis speculates that biodiversity was sacrificed because traditional systems of agriculture that were sometimes displaced (about 40% in the 1980s) and because the Green Revolution expanded agricultural development into new areas where it was once unprofitable or too arid.

Beyond the above considerations, there are the major environmental problems that arise with the intensive and extensive use of fertilizers and pesticides. Two examples are DDT and nitrogen loading.

DDT

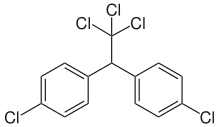

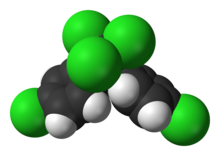

Dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane, commonly known as DDT, is a colorless, tasteless, and almost odorless crystalline chemical compound.

|

|

|

|

|

|

Originally developed as an insecticide, it became infamous for its environmental impacts. DDT was first synthesized in 1874 by the Austrian chemist Othmar Zeidler DDT's insecticidal action was discovered by the Swiss chemist Paul Hermann Müller in 1939. DDT was used in the second half of World War II to control malaria and typhus among civilians and troops.

Müller was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1948 "for his discovery of the high efficiency of DDT as a contact poison against several arthropods".

By October 1945, DDT was available for public sale in the United States. Although it was promoted by government and industry for use as an agricultural and household pesticide, there were also early concerns about its use.

Opposition to DDT was focused by the 1962 publication of Rachel Carson's book Silent Spring. It cataloged environmental impacts that coincided with widespread use of DDT in agriculture in the United States, and it questioned the logic of releasing potentially dangerous chemicals into the environment with little prior investigation of their environmental and health effects.

The book cited evidence that DDT and other pesticides had been shown to cause cancer and that their agricultural use was a threat to wildlife, particularly birds. Although Carson never directly called for an outright ban on the use of DDT, its publication was a seminal event for the environmental movement and resulted in a large public outcry that eventually led, in 1972, to a ban on DDT's agricultural use in the United States. A worldwide ban on agricultural use was formalized under the Stockholm Convention on Persistent Organic Pollutants, but its limited and still-controversial use in disease vector control continues, because of its effectiveness in reducing malarial infections, balanced by environmental and other health concerns.

Along with the passage of the Endangered Species Act, the United States ban on DDT was a major factor in the comeback of the bald eagle and the peregrine falcon from near-extinction in the contiguous United States.

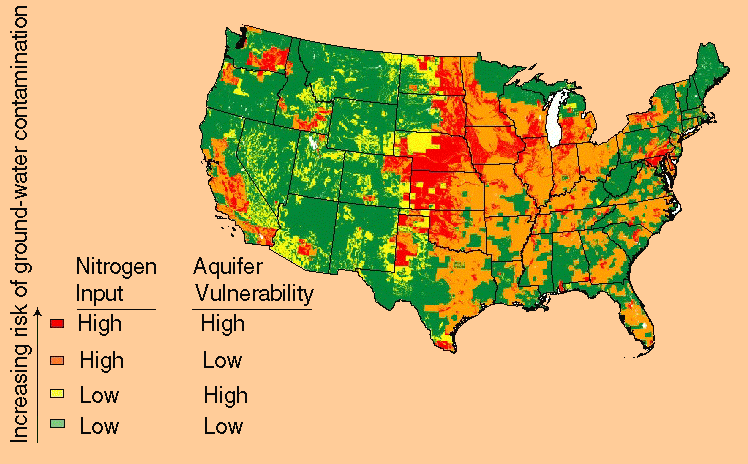

NITROGEN LOADING

Nitrogen loading refers to inputs from inorganic fertilizer, animal manure, and atmospheric deposition

Major nitrogen sources in coastal ecosystems include: atmospheric deposition onto land, freshwaters, the estuary, and onto impervious surfaces such as roads and parking lots; fertilizer use on farms, cranberry bogs, lawns, and golf courses; and wastewater from sewage and on-site septic systems. In many watersheds of southern New England septic systems are the primary contributors to groundwater nitrogen entering estuaries. Tidal exchange can introduce marine nitrogen, but this source is relatively unimportant relative to high nitrogen loads from the watershed.

Some nitrogen from atmospheric deposition evaporates and thus returns to the atmosphere. Some nitrogen (mainly ammonium) is adsorbed to soil particles and removed from further transport. Plants take up soil nitrogen (mainly in the form of nitrates) and effectively immobilize it. Thus, the vegetated landscape is important in sequestering nitrogen and slowing its transport to the sea.

Some of the nitrogen that enters the soil, subsoils, and groundwater is denitrified and therefore is lost to the system. (Denitrification is a term for a series of chemical reactions carried out by bacteria in which nitrogen in the form of nitrate is converted to inert nitrogen gas.) Any nitrogen that is not lost on its journey through a watershed will be transported eventually to the receiving estuary. The net difference between sources and losses represents the nitrogen loading to the estuary, usually expressed as an amount in kg per year.

Effects of nitrogen loading can vary among estuaries

Knowing the amount of nitrogen entering an estuary each year is of little use by itself because the amount of nitrogen that is beneficial or harmful to an embayment is site-specific. Tidal exchange is very important in determining whether nitrogen concentrations can reach excessive levels. Nitrogen entering a well-flushed estuary may quickly disperse to the open sea and therefore contribute little to eutrophication of the estuary. On the other hand, a poorly-flushed embayment may retain its nitrogen load for a long enough time to contribute to eutrophication and disruption of the system. Also, the size of the estuary or embayment will influence the concentration of nitrogen after it enters from the watershed.

Once in the estuary, nitrogen is rapidly taken up by algae and plant life, especially during warm, sunny days of spring and summer. Algae, both planktonic microscopic forms and seaweeds (macroalgae), generally respond fastest to new nitrate seeping into the estuary from the groundwater.

In the shallows of the estuary, beds of eelgrass comprise an important fish and shellfish habitat. Eelgrass can take nitrogen from the water through its leaves, but its effectiveness is compromised by the faster growing algae.

Rapidly growing phytoplankton make the water more turbid, decreasing the light necessary for eelgrass growth. Eelgrass becomes increasing starved for light, and more prone to disease and die-off as this stress continues. The eelgrass, which propagates both by runners and seeds, has difficulty replenishing itself. The result after several years of diminished growth and lack of replenishment is thinning of eelgrass and its eventual loss from the estuary.

How does excessive nitrogen lead to declines of fish and shellfish?

The eelgrass beds support the growth of many juvenile fishes, offering enhanced food and protection. As eelgrass is lost from the estuary, the fish community suffers dramatic declines in numbers and diversity of fish. As eelgrass is replaced by seaweeds (macroalgae), other indirect effects of excess nitrogen further diminish the ability of the estuary to sustain fish production.

In sunlight, the algae produce oxygen during photosynthesis. At night, they use oxygen during respiration. If the weather is cloudy, they cannot produce very much oxygen. During several successive cloudy, hot, windless days in Summer, the large numbers of algae can use up all of the dissolved oxygen and cause the suffocation of shellfish and finfish.

Janus was the ancient Roman god of polarities, whose head had two opposing faces one smiling and one frowning. That Science is Janus-like is illustrated by the Green Revolution described above and by nuclear energy, described in Lecture 16. In a different sense, the confidence that permeates our present understanding of the cosmos has a Janus-like quality.

In this and earlier lectures, the Big Bang theory was shown to account for important features of the Universe, for example, the abundances of light elements and the apparent expansion of our galactic-scale environment. That said, the cosmological models that describe the evolution of the Universe are based on an important assumption, that 90-95% of the Universe is “dark matter,” an assumption which has yet to be confirmed experimentally. There are two further problems, viz., the age problem (some stars appear to be older than the Universe itself), and the causality problem (no explanation is given for why the Universe popped out of its initially collapsed state).

Since dark matter has not been observed, we don’t know whether the Universe will continue to expand or, owing to Newton’s Law of Universal Gravitation (Lecture 3), reverse itself, and begin to collapse in a final Big Crunch,

Some quantum theorists have hypothesized that ours is only one among a whole litany of alternate universes.

Given the plethora of stars and galaxies in the heavens, probability theory presents a convincing argument that there should exist at least one star with one planet having just the right distance from that star and having approximately the same distribution of elements as Earth, so that life could have evolved on that planet. But, no one argues that the probability is one, a sure event. Some astronomers have even suggested that maybe we are alone in the Universe.

Thomas Aquinas (1225-1274) was an Italian, the foremost classical proponent of natural theology, arguing in his Summa Theologica (1265–1274) that reason is found in God. Saint Thomas embraced several ideas put forward by Aristotle, whom he called "the Philosopher," and attempted to synthesize Aristotelian philosophy with the principles of Christianity. Aristotle believed in the geocentric view of the universe, placing man at its center. This view was challenged by Copernicus in his De revolutionibus orbium coelestium (On the Revolutions of the Celestial Spheres), published just before his death in 1543, a major event in the history of science, triggering the Copernican Revolution.

But, Aquinas would have us believe in a God who created the Universe, de novo. His answer to St. Augustine’s question, “What was God doing before He created the Universe?” would be, I suppose, that He was thinking about it.