This week we looked at two examples of amazing Indigenous leaders in health research and practise. Take some time to research other examples of leaders in Indigenous health, and highlight one person b

Module 9: Spiritual Wellness and the Role of Ceremony ReadingsYou should complete the following readings prior to continuing with the Module Notes:

TextbookChapter 9: “miyo-pimatisiwin, “A Good Path”: Indigenous Knowledges, Languages, and Traditions in Education and Health. pp. 80-92. In, Determinants of Indigenous Peoples’ Health.

You should watch the following video when it is assigned within the context of this module:

Dr. Marcia Anderson TedxTalk (20 minutes): https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=IpKjtujtEYI

Sharing Our Wisdom (15 minutes): https://vimeo.com/168708896

Colonial policies and processes—including those we have reviewed so far—sought to eradicate Indigenous Knowledge. Premised on the notion that Western knowledge are more legitimate. As we saw in the chapter for this week, “the process of colonization has resulted in [Indigenous] traditions being devalued, denigrated, and alienated by mainstream society and specifically by the health system” (Steinhauer & Lamouche, p. 80). A lot of research on Indigenous peoples has also constructed them as “inferior, primitive, and deficient” (Rogers et al., 2019). Lately, however, there has been increasing recognition that Indigenous knowledge has value and should be integrated into health care research, policies, and practices.

In Chapter 9, the authors note that most mainstream health programming:

Does not include Indigenous spirituality or spiritual wellness components

Uses a deficit-based model

Does not address intergenerational trauma

Does not include the use of traditional teachings, Indigenous languages, ceremony, etc.

Because of these reasons, mainstream health programming is not always effective for Indigenous people. However, the authors also offer a strengths-based perspective in their message that “the greatest opportunity for the improvement of Indigenous communities and nations lies in the repositioning, revaluing, and reinvigation of traditional indigenous healing practices and concepts...” (Steinhauer & Lamouche, p. 81)

Building on this, it is important to note that culture is an important aspect of holistic wellness for Indigenous peoples. Culture is healing. For decades, Indigenous people have been calling for increased access to traditional forms of healthcare in urban and rural settings alike. This is reflected in the TRC Call to Action number 22:

“We call upon those who can effect change within the Canadian health-care system to recognize the value of Aboriginal healing practices and use them in the treatment of Aboriginal patients in collaboration with Aboriginal healers and Elders where requested by Aboriginal patients.”

Listen to Dr. Marcia Anderson talk about the importance of Indigenous knowledge, as well as how IK can be used to provide innovative programming to Indigenous peoples:

https://youtu.be/IpKjtujtEYI

Sharing Our Wisdom: Learnings from an Indigenous heath research projectSeveral years ago, I had the pleasure of working with the Institute of Aboriginal Health at UBC (now the Centre for Excellence in Indigenous Health). This work was centred on a community-based research project on traditional healthcare practises in urban settings. Located on the unceded territory of the Musqueam, Squamish and Tsleil-Waututh nations, Vancouver is also home to a diverse population of Indigenous peoples.

Before the start of this project, we formed the Indigenous Health Working Group, made up of a group of Elders, traditional healers, service providers, and knowledge keepers – all experts in Indigenous health who helped to develop the curriculum for a set of seven workshops (called Health Circles) that would introduce participants to different aspects of traditional health and healing. The research was also conducted in paartersnhip with health authority, the Musqueam Nation, and urban Indigenous organizations.

The goals of Sharing Our Wisdom were to:

Facilitate a healthier life context by engaging Aboriginal participants and learning about Aboriginal health practices

Address health inequities through the re-traditionalization and decolonization of health practices

Strengthen identity and self-determination (which can lead to better health outcomes), and

Build relationships in order to redress the harm that has been done to our peoples through colonization

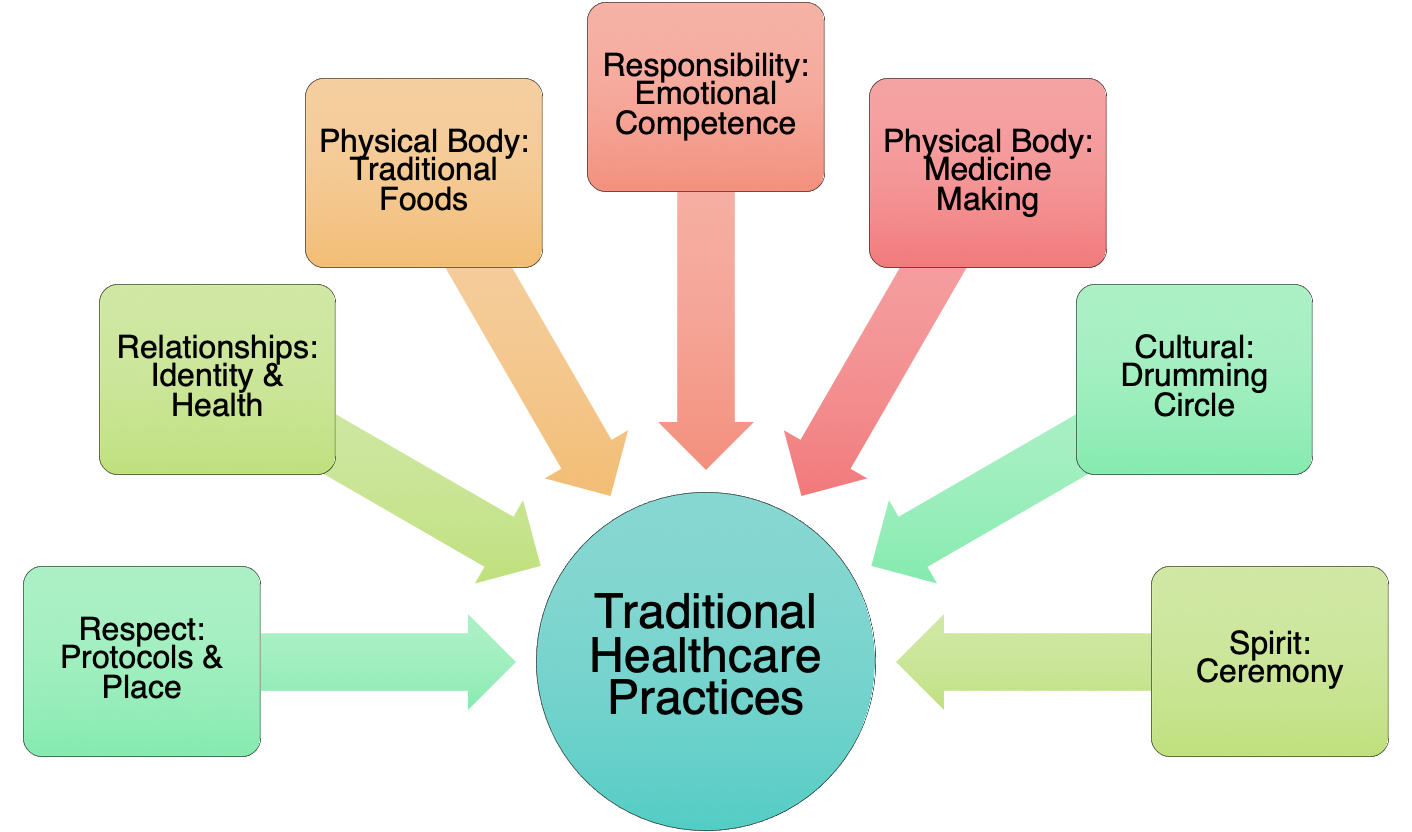

The topics introduced throughout the health circles (depicted in the diagram below) were as diverse as you might expect:

Please hear from some of the Elders and Knowledge Keepers that we worked with on this project: https://vimeo.com/168708896

Many participants spoke about the overall value of traditional medicines and their preference to access traditional healthcare, rather than mainstream, western healthcare. In speaking to their perspectives and experiences around accessing traditional healthcare, participants noted the value actually engaging in relationships and genuine connections between healers and community members:

"Doctors today don’t know who we are, especially when we are using walk-in clinics. Our traditional doctors knew us, they knew our family, and they talked to our ancestors in ceremony. If we got sick, our parents knew where to go, and not just to one person, there were different people in the community."

Participants also spoke about the importance the holistic nature of traditional healthcare. They specifically noted the positive impacts that these approaches have had on emotional wellness, which is often avoided through western medical approaches. Participants also attributed learning and healing in groups to an increased accountability and motivation to make positive changes in their personal healthcare practices.

The participants’ stories indicate that participating in the healing circles helped to increase knowledge of healthcare needs, options, and ownership over healthcare choices. Overall, participants were very clear in their call for greater support for traditional healthcare practices through policies to ensure that traditional healthcare practices are recognized, increased funding for culturally appropriate interventions, and continued research.

If you would like to learn more about this research, please contact me. I am always happy to discuss it!

Leaders in Indigenous HealthIn addition to the phenomenal work that Dr. Marcia Anderson highlights in her TedxTalk, there are other leaders in Indigenous health that are worth profiling. Here are two more:

Dr. Janet Smylie

Dr. Janet Smylie is a Family Physician, a Métis leader in Indigenous health research, and a Professor at University of Toronto. Dr. Smylie is an advocate for bridging traditional and western practice within healthcare, and conducts research on ending anti-Indigenous racism in the healthcare field. She identifies as a two-spirited mother and grandmother.

“Nobody is going to get better from a knowledge system that is very different from their own unless there is some kind of bridging. You have to work with people in a language and conceptual framework that fits for them” - Dr. Janet Smylie

Recently she has also taken a lead in assessing the impact that COVID-19 has had on First Nations, Inuit and Métis communities, which you can read about here: https://nowtoronto.com/lifestyle/health/toronto-trailblazers-janet-smylie/

Dr. Lori Arviso Alvord  Dr. Lori Arviso Alvord was the first female Navajo surgeon. She lives a cultural/professional dichotomy in which she strives to keep her values and beliefs at the heart of her work. She has continually fought negative stereotypes throughout her education and career. In the late 1990s, she co-authored an autobiography called The Scapel and the Silver Bear, and in the hope that her words will help current and future Aboriginal medical students in facing similar culturally-charged challenges.

Dr. Lori Arviso Alvord was the first female Navajo surgeon. She lives a cultural/professional dichotomy in which she strives to keep her values and beliefs at the heart of her work. She has continually fought negative stereotypes throughout her education and career. In the late 1990s, she co-authored an autobiography called The Scapel and the Silver Bear, and in the hope that her words will help current and future Aboriginal medical students in facing similar culturally-charged challenges.

After completing her medical training, she returned to her community to give-back: “although I could have had a more lucrative practice elsewhere… I knew that Navajo people mistrusted Western medicine, and that Navajo customs and beliefs… often stood in direct opposition to the way I was trained at Stanford to deliver medical care. I wanted to make a difference in the lives of my people, not only by providing surgery to heal them but also by making it easier for them to understand, relate to, and accept Western medicine” (Alvord & Cohen Van Pelt, 1999, p.13).

Can you think of other Indigenous leaders and role models in health? In our discussions this week, you will be asked to write about one!