The attachment is the question

0

Two of my favorite things about Paleolithic art are how long this era lasts and how little we know about it! There is no other era that remains as much of a mystery as Paleolithic Art. Art from the Paleolithic era is commonly identified as spanning an era from 40,000 years ago to 10,000 years ago (The Metropolitan Museum of New York City Introduction to Prehistoric Art). Yes, you read that correctly: this era lasts 30,000 years. Now try to wrap your head around how long ago that was—40,000 years ago to 10,000 years ago or from approximately the years 38,000 BCE to 8,000 BCE. I bet most of you think that someone who grew up in the United States without a cell phone is old. Well, in that case, the art from this era is older than old. To help put this in perspective, Apollo 11 landed on the moon in 1969 (47 years ago); in 1798 George Washington was sworn in as the first President of the United States (218 years ago); Columbus landed on "the new world" in 1492 (524 years ago); jumping a bit further back in time Cleopatra "queen" of Egypt) died in the year 30 (1,986 years ago); the Great Pyramids of Giza were completed in 2510 BCE (4,526 years ago). Now remember, the peoples who made Paleolithic art lived between the years (approximately) 38,000 BCE to 8,000 BCE.

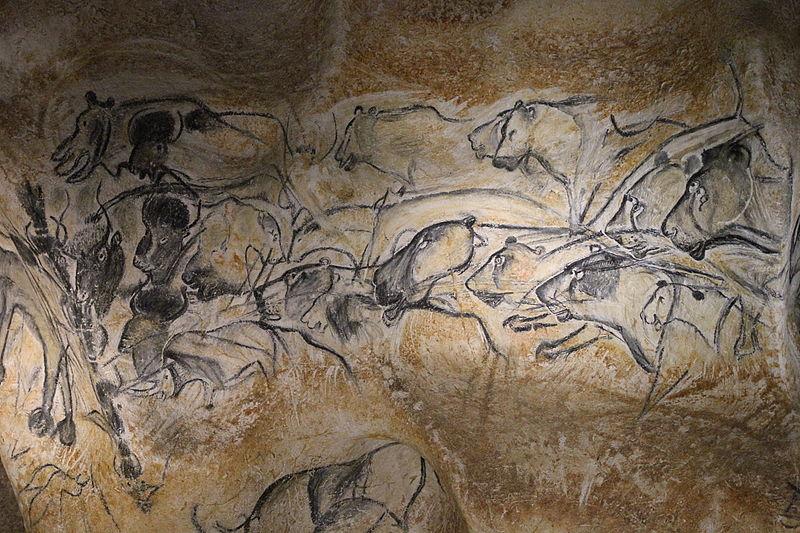

Art from this era, as well as the Neolithic era, is often called Pre-historic art. This is because the artwork pre-dates any known written language. I also find this fact to be deeply humbling. Try to think about what it would be like to live without written and minimal spoken communication (it is currently thought that Paleolithic peoples made expressive emotional sounds like laughing, crying, screaming, some hand gestures and a few basic words). Knowing the relatively limited communication skills of these peoples, particularly those whose “artwork” dates closer to the 30,000 BCE eras, influences how we study and analyze these works of art. For example, most of us look at the paintings in Chauvet-Pont-d'Arc Cave in southern France (see below) and could only *dream* of rendering such vivid, formally complex, representations! It is difficult for us to remember that the peoples who crafted these had limited verbal, and seemingly no written, communication skills!

"Lions Panel (right) Bisons (left)" by Claude Valette is licensed under BY-SA-4.0

Given that there are no written accounts from this era, it is exceptionally challenging to ascertain what function art from this era served and what this art meant to these people. To be sure, there are a *lot* of different kinds of "mark making" from this era that historians classify as art. Let's review a few of the most common:

1) Non-representational art/ornamentation

Non-representational art is the earliest kind of art humanity seems to have constructed. Non-representational means that the artwork doesn't represent any specific person, place, or thing. Rather, it is a kind of ornamentation or decoration (e.g., zig-zag or square patterns, dots, lines, etc.). For example, the image below is non-representational.

"Blombos Cave engraved ochre" by Chris S. Henshilwood is licensed under CC-BY-SA-3.0

This artifact was discovered in 2002 in a South Africa cave called Bomblos Cave and pre-dates most Paleolithic art. It is a lump of ocher that was "decorated" by mankind sometime between 68,000 BCE and 98,000 BCE. Amazing, right?! Or, maybe you are thinking, "This isn't amazing, my 5 year old could do that"! While that may be true, remember what era this object dates to and remember that historians, archeologists, and anthropologists point to humanities’ creative abilities as a defining feature of what it means to be human—no matter how basic that creation may seem to us today.

There's a *lot* of art that fits within this category, much of which has been engraved on cave walls. That doesn't mean that these are the only objects humans made at this time, this is just all we're able to prove that humans did make at this time. That raises an interesting question, how do historians determine the date of artifacts like this?

Ideally, historians would ask scientists to carbon date this object; but earth pigments like ochre (or any stone) are not able to be carbon dated (see http://hyperphysics.phy-astr.gsu.edu/hbase/nuclear/cardat.html for more details on Carbon dating). Historians and scientists were able to date the below work by carbon dating animal bone tools and animal fossils from the same layer of sediment in the rock. This is not uncommon, but why might this practice be a source of speculation behind dating Paleolithic art?

2) Representations of the human figure

Early representations of humans are most commonly found as sculptures in the round; however there are relief sculptures of humans as well. Interestingly, the vast majority of works representing humans depict females. While fragments of hundreds of tiny sculptures of women have been discovered across Eurasia, less than three are thought to represent males.

According to Karen D. Jennett’s honors research on Paleolithic figurines:

The images are, in most cases, naked portions of the female anatomy that follow a certain artistic style and are carved from different soft stones, ivory, or bone. A few rare examples are formed from clay and then fired, representing some of the earliest examples of ceramics (Baring 1991: 11). The most often pictured figurines are those that are carved so that certain parts of the anatomy are emphasized while others are deliberately neglected. The hair-styles, breasts, abdomen, hips, thighs and vulva are often exaggerated while the extremities (heads, arms, hands, legs, and feet) and facial features are often lacking. Of course there are many depictions of females that do not adhere to this form and therein lies one of the essential interpretive conflicts (Jennett, 2008).

I’ve always found these figures to be compelling—why is it that there are so many female figurines and why are so many similar features emphasized and/or de-emphasized? How do we explain those figurines that don't have these same characteristics? Later, we will examine interpretations of these figurative sculptures. Because I have a BFA (a Bachelor’s degree in Fine Arts), I often find myself analyzing the materials and techniques used to make works of art.

To carve any material, the artist/artisan subtracts (or removes by subtracting) the material (stone, wood, etc.) to create the final work. Subtractive sculpting is an unforgiving technique because the artist cannot afford to make any mistakes—once the material is subtracted, it cannot be re-adhered. To carve a sculpture, the artist must use a harder material than the one the artisan is attempting to carve. For instance, the Woman of Willendorf (see below) was carved out of limestone.

"Venus of Willendorf" by Matthias Kabel is licensed under CC-BY-2.5

Limestone is relatively soft—limestone ranks between a 3 and a 4 on the Mohs scale of hardness (for reference: gypsum, which you can carve with your fingernail, ranks between a 1.5 and 2 and diamond, the hardest recorded stone, ranks as a 10 on the Mohs scale). As a result, this sculpture was carved by forming shapes and incising lines with another, harder, stone. Some of you may be thinking, “Why didn’t they carve these with metal tools”? That is a great question: sculptures made at the time when metallurgy skills had been developed were still likely carved with stone. This is because early metallurgy involved manipulating tin (1.5 on Mohs scale), silver (2.5-3 on Mohs scale), and copper (3 on Mohs scale). Note the softness of all of these early metals. Might the fact that these sculptures were made by banging harder stone against softer stone influence the way these sculptures look?

The sculpture of "Venus of Willendorf" is also a sculpture in the round. Sculpture in the round is any sculpture that is completely three-dimensional and free-standing, or, not attached to any kind of a background. I always remember the definition of sculpture in the round because you have to be able view it from all sides, or, walk around it. A relief sculpture has a background. Imagine carving into your bedroom wall, that would be a relief sculpture because it has a background and you can't really walk around it (or at least, you aren't intended to).

There are minimal drawings or paintings of the human form. Most common is to see handprints or stencils of human hands (see below). These have long captured the imagination of modern humans—it is difficult to not resonate with the outlines of hands of such distant ancestors.

This work (Pech-merle cave, by Kersti Nebelsiek) is free of known copyright restrictions.

3) Representations of animals

Perhaps the most popular kind of Paleolithic art is parietal art. Parietal art is Pre-historic art found exclusively on cave walls—this can include drawings, paintings, etchings, relief sculpture, etc. Parietal art is where archeologists and historians have found the bulk of animal representations.

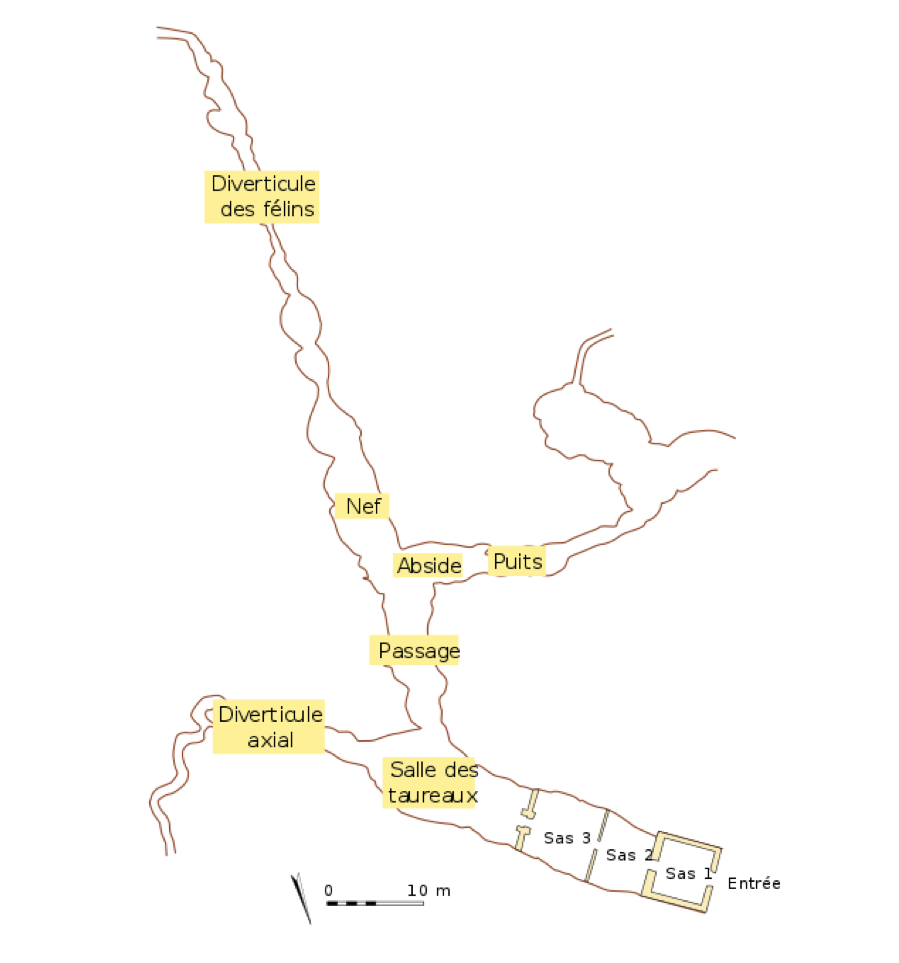

Perhaps what makes these most remarkable is not the fluidity with which most of these animal representations are crafted, but the remote locations in which they were located and discovered. It is estimated that the French cave Lascaux extends 770 feet into the cave and Chauvet-Pont-d’Arc extends 1,700 feet into darkness—and most of the images aren’t located near the entrance to the cave! See a map of the Lascaux below:

"Lascaux Plan" by 120 (V. Mourre/Inrap) is licensed under CC-BY-SA-4.0

This is not to say that there weren’t paintings outside of caves in mass quantities, the reality is that we only have those that were on walls inside caves that were sealed up, air tight and untouched for 10,000 to 40,000 years.

Imagine meandering your way through long, often narrow corridors. According to historian Mary Beth Looney, “The cave spaces range widely in size and ease of access. The famous Hall of Bulls [in Lascaux] is large enough to hold some fifty people. Other "rooms" and "halls" are extraordinarily narrow and tall” (Looney, retrieved 12 June 2017). You look up and the walls and ceiling are decorated with paintings and etchings of horses, bison, deer, elk, lions, mammoths, and even wooly rhinoceros—a panorama of prehistoric large-scale prehistoric wildlife. I have often wondered why these specific animals were represented. Certainly there were other animals that Paleolithic people were more likely to eat and come in contact with more frequently, like: mice, squirrels, and rats as well as insects including large beetles and grubs.

Detour to the cave: Let’s examine Lascaux more closely by checking out the website for the Cave of Lascaux, estimated to have paintings that date to 20,000 BCE. This link will virtually walk you through highlights of the cave. You can gain some insight on the depth of this cave by looking at the map of the cave in the bottom right corner of the web page. Scroll your mouse over to the small, white triangle on the left-middle side of the page—there read the links with additional information on this cave, including: parietal art and archeological research. Feel free to explore the rest of the links for additional information on this cave.

Lascaux was not the first parietal art to be discovered, that was the Spanish cave Altamira (discovered in 1879). It is also not thought to be the home of the worlds oldest known paintings, those date to 32,000-30,000 BCE and were discovered in 1994 in Chauvet-Pont-d’Arc. Lascaux is most famous because it was the first example of parietal art open for public view, which became permanently threatened by the mid-1960s. According to Mary Beth Looney:

The Caves of Lascaux are the most famous of all of the known caves in the region [southern France and northern Spain]. In fact, their popularity has permanently endangered them. From 1940 to 1963, the numbers of visitors and their impact on the delicately balanced environment of the cave—which supported the preservation of the cave images for so long—necessitated the cave’s closure to the public. A replica called Lascaux II was created about 200 yards away from the site. The original Lascaux cave is now a designated UNESCO World Heritage Site. Lascaux will require constant vigilance and upkeep to preserve it for future generations (Looney, retrieved 12 June 2017).

Of course, given my love for materials and techniques, I have also frequently marveled at how these images were made. In Lascaux, over 100 animal fat based lamps have been found; these burn low light (less than a candle) for nearly 24 hours. It is humbling to realize how little light they had to work by, especially in such long, dark caves!

The pigments used were derived from mostly earth minerals like ochre (an earthy pigment varying from light yellow to brown or red), chalk, manganese, and charcoal. They would use a variety of binders (often spit, fat, water, vegetable juices, urine, bone marrow, blood, and egg) to mix the pigments into a paste and to adhere the pigment to the surface of the cave wall. At times, cave walls were prepared prior to applying paint—this is most evident in Chauvet-Pont-d’Arc.

In caves like Altamira and Peche-Merle, Paleolithic peoples chose to paint on sections of the cave wall that had a similar, natural shape of the animals they were depicting. Early humans were so clever! For instance, in Altamira (see below) bison are painted on the parts of the ceiling that bulge out while in Peche-Merle a horse is painted on a part of the wall that is shaped like a horse’s head—each accentuating the shape or form of the animal.

"La Neocueva de Altamira" by José Miguel is licensed under CC-BY-NC-ND-2.0

"Bison in the cave of Altamira" by Daniel Villafruela is lisenced under CC-BY-3.0

Paint is thought to be applied using any number of tools. According to historian Michael Douma:

Historians hypothesize that paint was applied with brushing, smearing, dabbing, and spraying techniques. Large areas were covered with fingertips or pads of lichen or moss. Twigs produced drawn or linear marks, while feathers blended areas of color. Brushes made from horsehair were used for paint application and outlining. Paint spraying, accomplished by blowing paint through hollow bones, yielded a finely grained distribution of pigment, similar to an airbrush. The oxides of iron dug right out of the ground in the form of lumps were presumably rich in clay. This consistency was conducive to the formation of crayon sticks and also could be made into a liquid paste more closely resembling paint (2008).

I’ve actually tried the “paint spraying technique,” maybe we can give it a “go” in class! It is exceptionally hard and very messy. My experience indicates that those who painted using this method were highly trained.

Of course, as with representations of human figures, there is much debate surrounding the contextual analysis of these works (see the Contextual Analysis section in your Introducing Art History reading). Of primary concern is are basic questions surrounding the people involved in the creation, use, and viewing of the artwork—the patron, the artist and viewers and the larger social issues presented by the work of art. Let’s read what some scholars have hypothesized below: consider which parts of these analysis are indicative of a formal analysis (see the Formal Analysis section in your Introducing Art History reading) and which parts would be considered more of a contextual analysis. We will be scrutinizing these readings more closely in class, so be sure to read through them carefully. There are a total of 7 sources for you to read: 4 on the most famous figurative representation, the Woman of Willendorf, and 3 on parietal animal representations. Be sure to read these sources with a critical eye!

___________________________________________________________________________

On Figurative Representations:

Interpretation 1: George Grant MacCurdy—Recent discoveries bearing on the antiquity of man in Europe, 1910.

The most important piece of all was a female statuette of stone—the so-classed Venus of Willendorf…The figure is 11 centimeters high and complete in every respect. It is carved from fine porous oölitic limestone. Some of the red color with which it was painted still adheres to it. It represents a fat pregnant woman with large pendent mammæ and large hips, but no real steatopygy. It corresponds closely in form to the Venus of Brassempouy, an ivory figurine… The hair is kinky (negroid), the face is left unchiseled. The arms are much reduced, the lower arms and hands being represented only in slight relief. The knees are well formed, but below the knees the legs are much shortened, although provided with calves. The entire figurine is proof that the artist was a master at representing the human form and that here he intended to emphasize those parts most closely associated with fecundity. The only suggestion of apparel or ornament is a bracelet on each wrist. The fauna of this horizon includes the mammoth, horse, reindeer, stag, and fox… It was my good fortune to be in Vienna the week the Venus of Willendorf arrived, and, after the museum staff, to be the first archeologist to examine the specimen.

Interpretation 2: Marilyn Stokstad and Michael Cothren—Art History, 2014

The most famous of these, the Woman From Willendorf, Austria, dates from about 24,000 BCE. Carved from limestone and originally colored with red ocher, the statuette’s swelling, rounded forms make it seem much larger than its actual 4 3/8-inch height. The sculptor exaggerated the figure’s female attributes by giving it pendulous breasts, a big belly with a deep navel (a natural indentation in the stone), wide hips, dimpled knees and buttocks, and solid thighs. By carving a woman with a well-nourished body, the artist may have been expressing health and fertility, which could ensure the ability to produce strong children, thus guaranteeing the survival of the clan.

Interpretation 3: William Fleming—Art & Ideas, 1986

All across Ice Age Europe and Asia female images have been found. The featureless face of the figure known as the Woman of Willendorf exudes pride and contentment. She bends over her breasts and clasps them with tiny arms. In this and other such sculptures, the voluptuous contours, fleshy hips, huge bosoms, and exaggerate sex characteristics suggest mother goddesses of some fertility cult.

Interpretation 4: LeRoy McDermott—Self-Representation in Upper Paleolithic Female Figurines, 1996

This study explores the logical possibility that the first images of the human figure were made from the point of view of self rather than other and concludes that Upper Paleolithic “Venus” figurines represent ordinary women’s views of their own bodies. Using photographic simulations of what a modern female sees of herself, it demonstrates that the anatomical omissions and proportional distortions found in Pavlovian, Kostenkian, and Gravettian female figurines occur naturally in autogenous, or self-generated, information. Thus the size, shape, and articulation of their body parts in early figurines appear to be determined by their relationship to the eyes and relative effects of foreshortening, distance, and occlusion rather than by symbolic distortion. …As self portraits of women at different stages of life, these early figurines embodied obstetrical and gynecological information and probably signified an advance in women’s self-conscious control over the material conditions of their reproductive lives.

___________________________________________________________________________

On Animal Representations:

Interpretation 1: Dutton, D., Mirimanov, V., & Halverson, J., On Art for Art's Sake in the Paleolithic, 1987.

There remains another possibility, however, which is that Paleolithic art has no meaning, that is, that it had no religious-mythical-metaphysical reference, no ulterior purpose, no social use, and no particular adaptive or informational value. In other words, it was “art for art’s sake”…The Magdalenian [Paleolithic] painters, it seems safe to say, did not know they were creating “art,” but they certainly knew they were making representations.

It is obviously a difficult task to reconstruct the beginnings of figural representation with much assurance, but it is a fundamental problem, and I should like to suggest a possible sequence based primarily on what we know, or think we know, about media and technics in the archeological record. The first human artifacts, and for something like two million years the only ones, were stone tools. It is fair to assume the very early use of found tools and the manufacture of perishable wooden implements, but this does not affect the argument. The immemorial practice of stone-knapping provided the motor schema for carving. But carving, as distinct from chipping, required a new medium, one that did not fracture as flint or quarts did, and this was furnished by bone, ivory, and soft stone ( and probably wood). Our presumed earliest works of “art” art sculptures, and like stone tools they are three-dimensional, sculptures in the round. The next steps would be high and low relief, engraving, and finally painting, that is, a sequence gradually reducing the dimensionality of figural representation, step by step, from three or two. Of course, this sequence can probably never be substantiated, except perhaps for the first and last stages (painting is evidently later than sculpture in the round), for earlier modes would persist as newer ones developed. Judging by quality, especially visual verisimilitude, much relief sculpture, for example, must have been contemporaneous with cave painting. Nevertheless, it would seem to be a plausible sequence. In the beginning is the cutting tool, used first for carving, then for incising. There are many examples of engravings enhanced by paint, and the presence of paint in incised grooves verifies the sequence. The use of paint itself may well have begun much earlier with body decoration, making its application to images a simple step. The last stage before purely two-dimensional representation could have been the interesting and subtle one of enhancing naturally formed images by outlining and addition…The painting sequence then would go from body decoration to coloring engraved images to “bringing out” natural shapes to, finally, representation on any surface. Again, a step-by-step process is indicated involving the convergence of two media and one finally superseding the other.

The last stage, two-dimensional representation uninfluenced by the supporting surface, constitutes a considerable feat of abstraction. For stereoptic vision, a natural perception is three-dimensional. The ability to make two-dimensional figures that disregard the conformations of the surface they are painted on and to recognize their correspondence with real animals was a momentous development, completed by the representation of the third dimension itself in the form of rudimentary perspective (for example, the appropriate overlap of legs to indicate that one is behind another). It is representations by abstraction, and the image attains its own free-floating existence, independent of scene or surface. Such a sequence suggests a coevolution of technique and cognition, the internal image acquiring the same detachment of circumstance and particularity as the external image. Percepts become concepts. This horse becomes a horse, disembedded from the concrete (italics in original).

…In such a sequence no practical purpose need be inferred. For all people who can actually be observed, the creation of images is a pleasurable activity, autonomously rewarding. It is reasonable to assume that this was also true of prehistoric people.

Interpretation 2: Richard Bradely, Rock art and the Prehistory of Atlantic Europe: Signing the Land, 1997.

…His [Tim Ingold’s] argument works from the premise that territoriality is a way of ensuring co-operation between different groups of people who are exploiting the same resources but who are unlikely to meet very often. ‘It prevents adjacent groups, ignorant of each other’s positions, from traversing the same ground and thereby spoiling the success of their respective…operations. …mobile communities of different kinds are especially concerned to define their territorial rights in areas of above average population or in regions of unusually varied ecology.

How would such a system work in practice? In Ingold’s interpretation the process depends on what he calls ‘advertisement’. This procedure becomes necessary when different groups of people are not in direct contact with one another. Under those circumstances, ‘they must perforce communicate by other means than speech, and must indicate territorial limits by resorting to the “language” of signs. These signs have…to be “written down” onto the landscape (or seascape) in the form of durable boundary markers…Rock art may have been [a] medium by which communication of this kind was achieved…Although the details would have differed from one area to another, direct communication of any kind would have been unreliable and intermittent. In that case the essential feature would be that rock art provided one means by which different parties, who were not present on the same occasions, could communicate with one another.

Interpretation 3: David J. Lewis-Williams and Jean Clottes, The Mind in the Cave—the Cave in the Mind: Altered Consciousness in the Upper Paleolithic, 1998

During the Upper Paleolithic, we argue, the limestone caves of western Europe were regarded as topographical equivalents to the psychic experience of the vortex and a nether world. The caves were the entrails of the underworld, and their surfaces — walls, ceilings and floors —were but a thin membrane between those who ventured in and the beings and spirit-animals of the underworld. This is the context of west European cave art, a context created by interaction between universal neuropsychological experiences and topographically situated caves. When people of the Upper Paleolithic embellished these caves with paintings and engravings of animals, signs and, less commonly, apparently human figures, they were at times exploiting certain defined altered states to construct, in each cave, a particular, socially and historically situated underworld.

… This interpretation is strengthened by a common characteristic of certain hallucinations, again created by the wiring of the human nervous system and therefore universal. Hallucinations are often projected onto surfaces such as walls or ceilings. Western subjects liken this experience to a slide or film show: the visions "float" and move on the "screen.” Given the sensory deprivation afforded by the caves, and leaving aside for the moment all the other inducing factors, it is virtually certain that at least some Upper Paleolithic people must have hallucinated in them and, moreover, that some of those visions would have been projected onto the surfaces around them. Then, in an attempt to fix, to capture, those visions, we suggest that people searched the surfaces and added marks to re-create their mental images. The pictures that they thus made were not "pictures" in the usual sense of the word, nor were they representations of something else — their visions or, even less likely, "real" animals. Rather, they were visions, fixed forever.

…Often they feel themselves to be transformed into [these] animals, partially or completely. In shamanic thought, the shaman shares the power of his or her spirit-animal guide. In animal form, too, shamans believe that they can travel beyond their human bodies.

… Moreover, it seems highly probable that communal rituals were performed in these spaces. Each space was, in effect, a constructed segment of the underworld. Perhaps some of these rituals were preparatory to individual experiences to be sought by the few who ventured farther into the bowels of the underworld in search of spirit-animals. In solitary contemplation, experiencing sensory deprivation, searching with hands, sight and mind, some people found the spirit-animals for which they were questing and, then or later, fixed those visions and so acquired shamanic power and animal guides. The caves thus may have been socially differentiated not only by topography but also by images. Certain people may have been allowed into certain parts only. As the spectrum of consciousness was divided up and defined, so too were the caves socially differentiated. As people moved through the caves they established their personae or challenged the statuses of others. Both cave and art became instruments of social differentiation and contestation. Here, in the very origin of religion, were the seeds of its social divisiveness and domination, hierarchies and cruelties. Consciousness has always been a site of struggle.

--

Essay written by Dr. Karen Danielson

Bibliography

Douma, M., curator. (2008). Prehistory. In Pigments through the Ages. Retrieved June 12, 2017 from http://www.webexhibits.org/pigments/intro/early.html.

Jennett, K. (2008). Female Figurines of the Upper Paleolithic. Honors Thesis. Texas State University-San Marcos, Texas.

Looney, M., (n.d.). Lascaux. Retrieved June 12, 2017 from https://www.khanacademy.org/humanities/ap-art-history/global-prehistory-ap/paleolithic-mesolithic-neolithic/a/lascaux

Work sheet

Name: ____________________________

BEFORE reading “Paleolithic Art—The Oldest Art We Know Of” answer the following:

Approximately what date range does Paleolithic art span? ____________ to ____________

What do you think is the subject (or subject matter) of most Paleolithic art?

______________________________________________________________________________

______________________________________________________________________________

Why do you think early humans made “art”?

______________________________________________________________________________

______________________________________________________________________________

______________________________________________________________________________

Why do you think I put “art” in quotations above?

______________________________________________________________________________

______________________________________________________________________________

AFTER reading “Paleolithic Art—The Oldest Art We Know Of” answer the following:

Why is Paleolithic art difficult to date?

______________________________________________________________________________

______________________________________________________________________________

Why is pre-historic art difficult to understand?

______________________________________________________________________________

______________________________________________________________________________

______________________________________________________________________________

This essay discusses 3 different kinds Paleolithic “mark making”. What are they?

________________________________________________________

________________________________________________________

________________________________________________________

What are some basic things an artist needs to consider when carving a work of art?

______________________________________________________________________________

______________________________________________________________________________

In what ways might the technique of carving influence the appearance of the “Venus of Willendorf”?

______________________________________________________________________________

______________________________________________________________________________

______________________________________________________________________________

What do you think is most remarkable about Paleolithic Parietal art?

______________________________________________________________________________

______________________________________________________________________________

What are some basic things an artist needs to consider when creating parietal art?

______________________________________________________________________________

______________________________________________________________________________

At the end of this reading were three contextual analyses of the parietal art. What was the main argument that each author makes:

Interpretation 1: ____________________________________________________________

___________________________________________________________________________

___________________________________________________________________________

Interpretation 2: ____________________________________________________________

___________________________________________________________________________

___________________________________________________________________________

Interpretation 3: ____________________________________________________________

___________________________________________________________________________

___________________________________________________________________________

What questions do you have about the reading or because of the reading?

______________________________________________________________________________

______________________________________________________________________________

______________________________________________________________________________

______________________________________________________________________________