See the attached question

20

THE ORIGINS OF SLAVERY IN AMERICA

Early PhotographyBy modern standards, nineteenth-century photography can appear rather primitive. While the stark black and white landscapes and unsmiling people have their own austere beauty, these images also challenge our notions of what defines a work of art.

Photography is a controversial fine art medium, simply because it is difficult to classify—is it an art or a science? Nineteenth century photographers struggled with this distinction, trying to reconcile aesthetics with improvements in technology.

The Birth of Photography

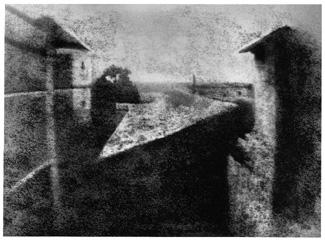

Joseph Nicéphore Niépce, View from the Window at Gras (1826)

Although the principle of the camera was known in antiquity, the actual chemistry needed to register an image was not available until the nineteenth century.

Artists from the Renaissance onwards used a camera obscura (Latin for dark chamber), or a small hole in the wall of a darkened box that would pass light through the hole and project an upside down image of whatever was outside the box. However, it was not until the invention of a light sensitive surface by Frenchman Joseph Nicéphore Niépce that the basic principle of photography was born.

From this point the development of photography largely related to technological improvements in three areas, speed, resolution and permanence. The first photographs, such as Niépce’s famous View from the Window at Gras (1826) required a very slow speed (a long exposure period), in this case about 8 hours, obviously making many subjects difficult, if not impossible, to photograph. Taken using a camera obscura to expose a copper plate coated in silver and pewter, Niépce’s image looks out of an upstairs window, and part of the blurry quality is due to changing conditions during the long exposure time, causing the resolution, or clarity of the image, to be grainy and hard to read. An additional challenge was the issue of permanence, or how to successfully stop any further reaction of the light sensitive surface once the desired exposure had been achieved. Many of Niépce’s early images simply turned black over time due to continued exposure to light. This problem was largely solved in 1839 by the invention of hypo, a chemical that reversed the light sensitivity of paper.

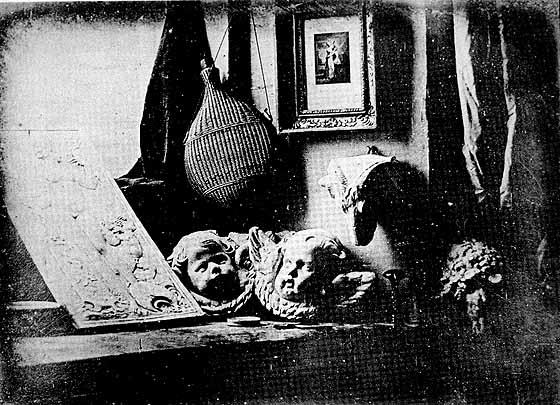

Louis Daguerre, The Artist's Studio, 1837, daguerreotype

Technological ImprovementsPhotographers after Niépce experimented with a variety of techniques. Louis Daguerre invented a new process he dubbed a daguerrotype in 1839, which significantly reduced exposure time and created a lasting result, but only produced a single image.

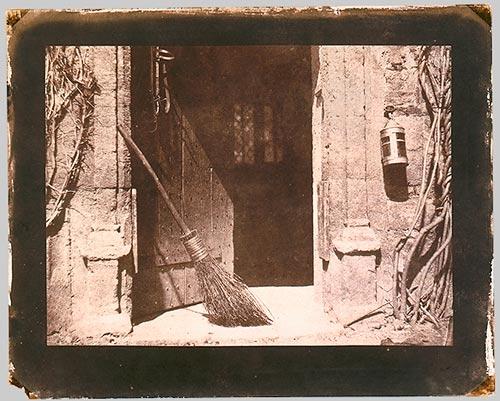

William Henry Fox Talbot, The Open Door, 1844, Salted paper print from paper negative

Jaques Louis Monde Daguerre

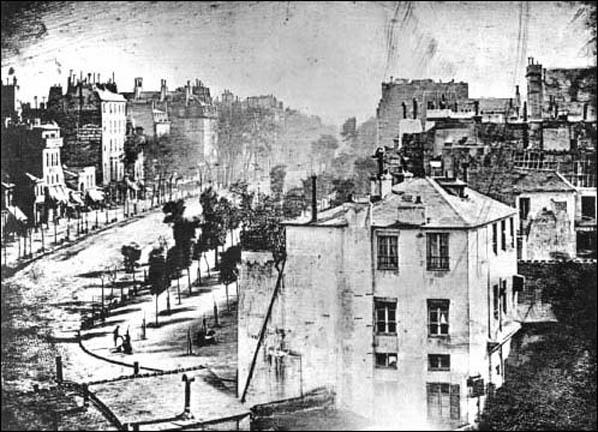

Louis Daguerre, Paris Boulevard, 1839, Daguerreotype

The DaguerreotypeAn early example of a “daguerreotype.” Paris Boulevard is a significant step in the development of photography. Taken in 1839 by Louis-Jacques Mande Daguerre, the photograph depicts a seemingly empty street in Paris. The elevated viewpoint emphasizes the wide avenues, tree-lined sidewalks, and charming buildings of the French capital. However, the obvious day light of the photograph begs the question – where are all the people in this normally busy city?

Enhanced version of Joseph Nicephore Niépce, View from the Window at Gras, 1826 or 1827, oil-treated bitumen, 20 x 25 cm

The answer to this question lies in the daguerreotype technique. The first photographs, such as Joseph Nicephore Niépce's famous View from the Window at Gras, took about 8 hours to expose, creating indistinct, grainy images. Daguerre was intrigued by these experiments and formed a partnership with Niépce from 1828 until the latter’s death in 1833. Daguerre continued to refine the photographic method until he developed his new process.

ChemistryHis technique consisted of exposing a copper plate coated in silver and sensitized with iodine to light in a camera, and then developed it in darkness by holding it over a pan of heated vaporizing mercury. He also developed a method of creating a permanent image by using a solution of ordinary table salt. Daguerre’s technique significantly reduced exposure time and created a lasting result that would not dim with further exposure to light, but only produced a single image. It would be up to others to produce the negatives that allowed for the production of multiple copies of an image.

Making Daguerreotypes A Shoe Shine

Louis Daguerre, detail Paris Boulevard, 1839, Daguerreotype

Daguerre’s Paris Boulevard shows the advantages of the new technique. There is far more detail than in earlier photographs. We can clearly see the panes in the windows and the sharp corners of the building in the front of the image. The objects are no longer blurry masses of light and dark, but defined and separate structures. In fact, the only thing missing are the people, except for the small figure of a man having his shoes shined at a sidewalk stand.

The remaining problem of the daguerreotype, at least by modern standards, was the long exposure time, between 10 and 15 minutes. This meant that the people hurrying along those spacious sidewalks did not register on the photograph. The man having his shoes shined, possibly the first photographic image of a person, obviously stayed still long enough to register on the image. The haunting empty, yet evocative, image of Paris Boulevard shows both how far photography had come in a short time and how much farther the technology still had to advance.

At the same time, Englishman William Henry Fox Talbot was experimenting with his what would eventually become his calotype method, patented in February 1841. Talbot’s innovations included the creation of a paper negative, and new technology that involved the transformation of the negative to a positive image, allowing for more that one copy of the picture. The remarkable detail of Talbot’s method can be see in his famous photograph, The Open Door (1844) which captures the view through a medieval-looking entrance. The texture of the rough stones surrounding the door, the vines growing up the walls and the rustic broom that leans in the doorway demonstrate the minute details captured by Talbot’s photographic improvements.

Wet Collodion PhotographsThe collodion method was introduced in 1851. This process involved fixing a substance known as gun cotton onto a glass plate, allowing for an even shorter exposure time (3-5 minutes), as well as a clearer image.

The big disadvantage of the collodion process was that it needed to be exposed and developed while the chemical coating was still wet, meaning that photographers had to carry portable darkrooms to develop images immediately after exposure. Both the difficulties of the method and uncertain but growing status of photography were lampooned by Honoré Daumier in his Nadar Elevating Photography to the Height of Art (1862). Nadar, one of the most prominent photographers in Paris at the time, was known for capturing the first aerial photographs from the basket of a hot air balloon. Obviously, the difficulties in developing a glass negative under these circumstances must have been considerable.

The Wet Collodion ProcessFurther advances in technology continued to make photography less labor intensive. By 1867 a dry glass plate was invented, reducing the inconvenience of the wet collodion method.

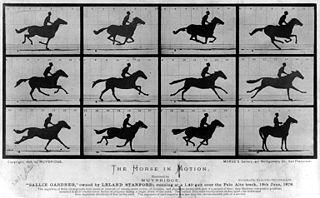

Prepared glass plates could be purchased, eliminating the need to fool with chemicals. In 1878, new advances decreased the exposure time to 1/25th of a second, allowing moving objects to be photographed and lessening the need for a tripod. This new development is celebrated in Eadweard Maybridge’s sequence of photographs called Galloping Horse (1878). Designed to settle the question of whether or not a horse ever takes all four legs completely off the ground during a gallop, the series of photographs also demonstrated the new photographic methods that were capable of nearly instantaneous exposure.

Eadweard Muybridge, The Horse in Motion ("Sallie Gardner," owned by Leland Stanford; running at a 1:40 gait over the Palo Alto track, 19th June 1878)

Iinally in 1888 George Eastman developed the dry gelatin roll film, making it easier for film to be carried. Eastman also produced the first small inexpensive cameras, allowing more people access to the technology.

Photographers in the 19th century were pioneers in a new artistic endeavor, blurring the lines between art and technology. Frequently using traditional methods of composition and marrying these with innovative techniques, photographers created a new vision of the material world. Despite the struggles early photographers must have had with the limitations of their technology, their artistry is also obvious.

Essay by Dr. Rebecca Jeffrey Easby

Is photography accurate? Challenges posed by the advent of Photography What follows is one portion of Dan Schiller's article, PHOTOGRAPHY AND PHOTOGRAPHIC REALISM IN 19TH CENTURY AMERICA: A THEORETICAL PERSPECTIVE.Prior to reading this article, you will want to know what the terms "objectivity" and "subjectivity" mean. See below:

Objective: (of a person or their judgment) not influenced by personal feelings or opinions in considering and representing facts.

Subjective: based on or influenced by personal feelings, tastes, or opinions.

While reading this article, answer the below questions:

The article references documents from the 1800s where those who take a Daguerreotype are repeatedly referred to as an operator, why do you think this is the case?

What are three reasons that why people have thought/think that photography is undeniably accurate?

Why were accuracy and reliability important ideals when photography was invented?

Why does the author claim that it is incorrect and misleading to think that, "photographs are equivalent to reality itself"?

Worldwide, the cultural impact of daguerreotypy, the first major photographic technology, was immediate and far-ranging. The French government's gesture of benevolence which freed daguerreotypy from most international patent restrictions was undoubtedly pivotal: before the end of 1839- the year which marked the consolidation of the technical achievement- Daguerre's pamphlet describing his process had been published in 30 editions, ((in nearly as many languages" (Rudisill 1971: 48).

Daguerreotypy's entrenchment was nowhere else as quick and as general as in the United States. Newhall (1976:33), an authority on early photography, asserts that by 1845 (daguerreotypes were so popular in America that the word was assimilated ... into everyday language." A best-selling periodical, Godey's Lady's Book, stated in 1849:

A few years ago it was not every man who could afford a likeness of himself, his wife or his children; these were luxuries known only to those who had money to spare; now it is hard to find the man who has not gone through the "operator's" hands from once to half-a-dozen times, or who has not the shadowy faces of his wife and children done up in purple morocco and velvet, together or singly, among his household treasures [Rudisill 1971: 70].

The same sort of ethnographic detail was repeated in 1853, when a New York Tribune article boasted tellingly of the stature of American daguerreotypy at the International Exhibition of Art and Industry, then underway:

If there be any one department in the whole building which is peculiarly American, and in which the country shines preeminent, it is in that of Daguerreotypes... In contrasting the specimens of art which are taken here with those taken in European countries, the excellence of American pictures is evident. ... our people are readier in picking up processes and acquiring the mastery of the art than our trans-Atlantic rivals. Not that we understand the science better, but the details of the art are acquired in a shorter time by us, while the enormous practice which our operators enjoy combines to render the daguerreotype a necessary contributor to the comforts of life. Does a child start on the journey of existence, and leave his "father's halls"; forthwith the little image is produced to keep his memory green. Does the daughter accept the new duties of the matron, or does the venerated parent descend into the grave, what means so ready to revive their recollection? Does the lover or the husband go to Australia or California, and not exchange with the beloved one the image of what afforded so much delight to gaze upon? The readiness with which a likeness may be obtained, the truthfulness of the image, and the smallness of the cost, render it the current pledge of friendship; and the immense number of operators who are supported by the art, in this country, shows how widely the love of sun-pictures is diffused 7 [Greeley 1 85 3: 1 71 -1 72].

Rudisill (1971: 198) estimates that by 1850 Americans spent between eight and twelve million dollars a year on photographs. One company, the Edward & H. T. Anthony photographic company, had sales of $600,000 in 1864 (Jenkins 1975: 50). And in 1872 a massive collection of essays on The Great Industries of the United States calculated on the basis of figures gathered on the importation of special albumenized photographic paper, that 50,400,000 photographs were made every year (Greeley et al. 1872:880).

Daguerreotypes were no longer the only form of photography; even by 1851, they were being replaced by the collodion process. The latter, being a negative-positive process (daguerreotypy was a direct positive process, which meant that a single copy of each image was the limit for each exposure), offered the commercially enticing possibility of multiple prints together with lower costs (cf. Jenkins 1975:39). Also, in the late 1850s,

one of the early major mass consumer items was born. The stereoscope viewer and box of view cards were as common a feature of the post-Civil War American home as is the television set, today [Jenkins 1975:50].

"Stereoviews," which have faded almost completely from the contemporary scene, were vastly popular throughout the latter 19th century; in 1901, a single producer of stereo views (Underwood) manufactured over seven million of them (Darrah 1964:1 09). By the 1880s and 1890s, the individuation of photographic picture-taking competence was well underway, as cameras began to be mass-marketed but, decades earlier, the diffusion of photographic images was already through. Generated by a ubiquity of pictures, the sign system of American photographic realism drew heavily on the unappealable, exclusive and universally recognizable accuracy attributed to these images (boldfaced added). Writing in 1840, Edgar Allen Poe stated:

In truth, the daguerreotype plate is infinitely more accurate than any painting by human hands (boldface added). If we examine a work of ordinary art, by means of a powerful microscope, all traces of resemblance to nature will disappear-but the closest scrutiny of the photographic drawing discloses only a more absolute truth, more perfect identity of aspect with the thing represented [Rudisill 1971: 54].

As if to denote the mechanical certainty of the process and its result, daguerreotypists were commonly termed “Operators." The "accuracy" which earned Poe's wonderment has, until recently, reigned unchallenged as the dominant standard of interpretation for photography-indeed, it may still so serve. Ivins, for example, believed that photographs

were exactly repeatable visual images made without any of the syntactical elements implicit in all handmade pictures [1953: 122].

This purported lack of syntax, this transparency of form, is obviously problematic. Throughout her remarkable book, Visual Communication and the Graphic Arts, Jussim convincingly demolishes such notions:

If there is a possibility that "photography" can be subjective, that what it records can be manipulated by an individual or restricted either by the technological limitations of lens or emulsion or by "artistic", i.e., subjective, manipulations in the making of photographic positives on paper, then we must admit that the purely objective character of photography as posited by Ivins is a fiction [1974:298].

...From the very first, therefore, photographic accuracy was remarked upon and accorded the highest status. One must wonder whether this could have occurred if "accuracy" had not been motivated, in society, by the rationalization of production by the simultaneous and intertwined needs for precise machine tools, for a labor force capable and willing to relinquish old procedures and tools and embrace new technologies, and for sales records and accounting procedures able to reliably itemize, record and justify incomes and expenditures to members of corporations, themselves a newly emerging legal entity. The concern for reliability certainly took on new importance in science at this juncture. Hobsbawm (1975: 269), for instance, mentions that

"Positive" science, operating on objective and ascertained facts, connected by rigid links of cause and effect, and producing uniform, invariant general "laws" beyond query or willful modification, was the master-key to the universe, and the nineteenth century possessed it [1975:269].

It is vital, though, to qualify and perhaps to restrict somewhat the actual impact of scientific thought [had] on the development of technology; for recent work seems to indicate that the function of science as a justificatory and explanatory belief-system may sometimes take precedence over its ability to engender operational technologies. Ferguson (1977:833) contends, for example, that "the organization of American technology in the first half of the 19th century tended naturally to follow the pattern set by the world of art." The reason he gives is that artists embodied the nonverbal knowledge which alone could guide precise and proficient construction of workable new technologies. Following the thought slightly further, Daguerre himself may be cited as an important example of the guidance by the art of technology - in this case, of photography.

Samuel Morse, the artist, scientist, and inventor who did most to bring photography at once to the United States (B. Newhall 1976:15-27), provides another good instance. In a speech to the National Academy of Design in 1840, Morse asserted that daguerreotypes were:

painted by Nature's self with a minuteness of detail, which the pencil of light in her hands alone can trace, and with a rapidity, too, which will enable (the artist) to enrich his collection with a super-abundance of materials and not copies; they cannot be called copies of nature, but portions of nature herself [Rudisill 1971: 57].

Seemingly both of and about nature, both imitator and imitated, daguerreotypy drew a compelling force from its apparently effortless transcendence of the order of human fallibility. As Jussim observes:

The photograph unquestionably stood for the thing itself. It was not viewed as a message about reality, but as reality itself, somehow magically compressed and flattened onto the printed page, but, nevertheless, equivalent to, rather than symbolic of, three-dimensional reality [1974:289] (boldfaced added).

It should be evident that despite its central importance as a cultural construct, the notion that photographs are equivalent to reality itself is both mistaken and fundamentally misleading. In Worth's phrasing,

it is impossible-physiologically and culturally- by the nature of our nervous system and the symbolic modes or codes we employ, to make unstructured copies of natural events [1976:15].

Nevertheless, photography's uncanny ability seemingly to re-present reality-to depict, without human intervention, an entire world of referents-apparently ensured its universal recognizability as a standard of accuracy and truth. "The Daguerreolite," an article published in the Cincinnati Daily Chronicle on January 17, 1840, articulated these features in lastingly significant terms:

Its perfection is unapproachable by human hand, and its truth raises it high above all language, painting, or poetry.It is the first universal language, addressing itself to all who possess vision, and in characters alike understood in the courts of civilization and the hut of the savage. The pictorial language of Mexico, the hieroglyphics of Egypt are now superseded by reality 14 [Rudisill 1971: 54] (boldface added).

Here, then, is the basis for notions of a universal language of art which Worth has rightfully attacked:

the knowledge that there are many codes and languages of speaking-does not seem to extend to our understanding of visual signs. Somehow as soon as we leave the verbal mode we begin to talk about universal languages... We seem to want very much to believe that by the use of pictures we can overcome the problems attendant to words and in particular to different languages. Somehow the notion persists that ... pictures in general, (have) no individual cultures that "speak" ... in differing languages, or articulate in differing codes 15 [1978:1-2].

...the universality accorded to the language of photography was an exclusive standard of truth, as well. Scharf (1974:23) writes

that the traditional concern with the camera obscura and other implements helped to prepare the way for the acceptance of the photographic image and accommodated the growing conviction that a machine alone could become the final arbiter in questions concerning visual truth (boldface added).

As early as 1842 the 27th United States Congress had accepted daguerreotypes as "undeniably accurate evidence in settling the Maine-Canada boundary" (Rudisill 1971: 240). And, in 1851, a panoramic series of daguerreotype views of San Francisco elicited the following comment in Alta California, a local paper:

It is a picture, too, which cannot be disputed - it carries with it evidence which God himself gives through the unerring light of the world's greatest luminary .... (the view) will tell its own story, and the sun to testify to its truth .... [Newhall 1976: 86] (boldface added).

The very word "daguerreotype" "soon came to be applied to any study of society which laid claim to sharp observation and total honestly [sic] 16 (Wilsher 1977:84).

Photographic realism, therefore, posited that to the correspondence between the work of art and "reality," which earlier realism had engendered, should be added a rigid belief in the scientifically symmetric and accurate, exclusive, and universally recognizable nature of their relation. So empowered, photography would hold its creators to account by redefining the ways in which people saw. As Rudisill views it,

a common ground of trust was soon established which equated a picture made by the camera with the truth of a direct perception. Once this sort of reliability was attributed to the medium and it was placed into wide use, it was inevitable that national imagery should henceforth have to base itself on the evidence of the machine. Political candidates must "daguerreotype" themselves on the public imagination; popular portraiture of statesmen, entertainers, or criminals in the press had to credit origin in the daguerreotype when laying claim to accuracy [1971: 231] (boldface added).

Photography paradigmatically revised the nature of "accuracy"; for, rather than merely manipulating symbols, photography appeared and claimed to reveal Nature. Thus, the major point: photographic realism made it no longer acceptable for the truth to be a visibly symbolic creation. Art and science both had to depict natural truth or else renounce their claims to accuracy and, therefore, to truth itself. Examples of the succeeding redefinition may be drawn from both enterprises. Edward Hitchcock, Professor of Geology (and President of Amherst College), wrote in 1851:

What new and astonishing avenues of knowledge. ... (I speak) of those new channels that will be thrown open, through which a knowledge of other worlds and of other created beings, can be conveyed to the soul almost illimitably .... [Rudisill 1971: 91].

Photography must be accorded a central place in the history of astronomy (Taft 1938: 198-200); in geographic and other scientific exploration (Newhall 1976:84-91); and in cartography (Woodward 1975:137-155). In general, as Ivins tells us, photography, although not a perfect report, nonetheless "can and does in practice tell a great many more things than any of the old graphics processes was able to" (1953: 139).

Likewise in art, photographic realism redefined the nature of the endeavor. An example from a slightly later time may serve best: I offer Eadweard Muybridge 's photographic studies of animal motion, conducted in the 1870s and 1880s.18 His pictures of horses "contradicted almost all of the previous representations made by artists" in showing that the animals had all four legs off the ground during the trot, canter, and gallop (Scharf 1974:213). Since photography had clearly exposed "the error of the old theory of the gallop," and since the technology's claim to accuracy was final and exclusive, a wide class of contemporaries insisted that "artists will no more be able to claim that they represent nature as she seems, when they depict a horse in full run in a conventional manner, or in the mythical gallop" (the writer is J.D. B. Stillman in The Horse in Motion [1882], in Scharf 1974: 216). Consequently, after Muybridge's photographs became available in France, for example, "figures of the horse in the conventional gallop no longer appear in the work of Degas" (Scharf 1974:206). To remain true to the new form of visual truth, the content of art and the practice of artists had to change.19,20

The most crucial consequences of this shift for symbolic production and appreciation have been extensively studied by Gerbner and Gross (1976). Their "cultivation analyses" of television's impact on viewers reveal substantial differences between the social worlds which light and heavy viewers of this eminently photographically realistic medium will construct. As they put it,

The premise of realism is a Trojan horse which carries within it a highly selective, synthetic, and purposeful image of the facts of life [Gerbner and Gross 1976:178].

In other words, photographic realism permits (indeed, forces) "the social tasks to which presumably 'objective' news, 'neutral' fiction, or 'nontendentious' entertainment lend themselves" (Gerbner 1973a:267) to remain hidden behind the transparent cloak of the "natural world." Correspondingly, the more convincingly this world is enunciated according to realist conventions,

the nearer its approach to living reality, the more significant would the symbolic function of the picture become because the observer could better respond to the picture as if to reality itself [Rudisill 1971: 13] (boldface added).

When a culture both proposes and abides by a standard which, like photographic realism, is inescapable, universal and exclusive - then events which employ the conventional language of this standard become "true events" regardless of their actual truth value. In no other way, I think, can we explicate the relation signified by the thousands of letters written and sent each year to seek advice from the "fictional" Dr. Marcus Welby.

On one hand, then, since photographic realism becomes historically ubiquitous to the extent that it is both accessible to and competently appreciated by the mass of the population, it harbors a growing capacity for the presentation of "truths" which are unappealing to various groups or strata who nonetheless likewise employ the style of photographic realism. On the other hand, to the extent that the inevitably concrete content which forms the very measure of competent appreciation is provided by centrally produced, systematically selected, often iterative codes, the latter will tend, relatively autonomously, to cultivate hegemonic, institutionalized rules of social morality. It is, furthermore, vitally significant that these two fundamental aspects of photographic realism need not be, and usually are not, "in sync." This follows from the subordination of photographic realism to commercial endeavor[s]-which may mobilize as a content material which may offend or even alarm the stratum or class which patterns its specific symbolic form. Thus contemporary reformers are incensed over the depiction of televised violence per se, regardless of the symbolic functions served by constant repetition of scenarios in which the poor, the weak and the old are taught to be fearful of attempts to change their plight.