Please see the attached for the question

54

THE ORIGINS OF SLAVERY IN AMERICA

Ancient AfricaThe origins of African art exist long before recorded history, beginning with the evolution of the human species. Over time, the continent became increasingly diverse in culture, politics, and religion.

Africa is considered the oldest inhabited territory on Earth, where the human species originated. During the middle of the 20th century, anthropologists discovered evidence of human occupation as early as seven million years ago. Their findings included fossil remains of early hominid species thought to be ancestors of modern humans.

Early CivilizationsThroughout humanity’s prehistory, Africa had no nation-states and was instead inhabited by groups of hunter-gatherers such as the Khoi and San. The domestication of cattle preceded agriculture. It is speculated that by 6,000 BCE, cattle were already domesticated in North Africa. In 4,000 BCE, climate change led to increasing desertification, which contributed to migrations of farming communities to the more tropical climate of West Africa.

By the first millennium BCE, ironworking began in Northern Africa and quickly spread across the Sahara into the northern parts of sub-Saharan Africa. By 500 BCE, metalworking was fully established in many areas of East and West Africa. Copper objects from Egypt, North Africa, Nubia, and Ethiopia dating from around 500 BCE have been excavated in West Africa, suggesting that trans-Saharan trade networks had been established by this date.

At about 3300 BCE, the Pharaonic civilization of Ancient Egypt came to power, a reign that lasted until 343 BCE. Egyptian influence reached deeply into modern Libya, north to Crete and Canaan, and south to the kingdoms of Aksum and Nubia.

European exploration of Africa began with Ancient Greeks and Romans. In 332 BCE, Alexander the Great founded Alexandria in Egypt, which would become the prosperous capital of the Ptolemaic dynasty after his death. Following the conquest of North Africa’s Mediterranean coastline by the Roman Empire, the area was integrated economically and culturally into the Roman system. Christianity soon spread across the region.

In the early seventh century, the newly formed Arabian Islamic Caliphate expanded into Egypt and then into North Africa. Islamic North Africa became a diverse hub for mystics, scholars, jurists, and philosophers. Islam spread to sub-Saharan Africa, mainly through trade routes and migration.

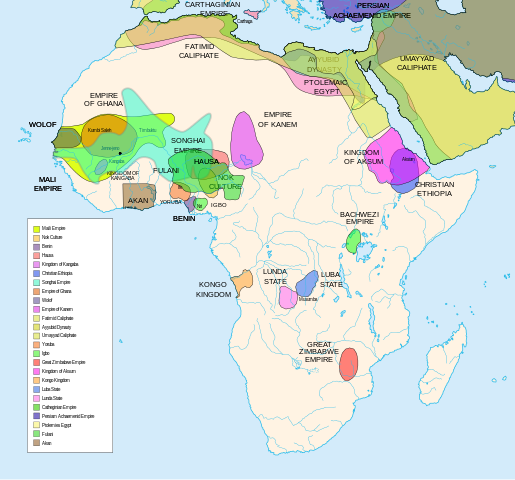

Ninth to Eighteenth CenturiesPrecolonial Africa possessed as many as 10,000 different states and polities characterized by many sorts of political organization and rule. These included small family groups of hunter-gatherers, such as the San people of southern Africa; larger, more structured groups, such as the family clan groupings of the Bantu-speaking people of central and southern Africa; heavily structured clan groups in the Horn of Africa; the large Sahelian kingdoms; autonomous city-states and kingdoms such as those of the Akan; Edo , Yoruba , and Igbo peoples in West Africa; and the Swahili coastal trading towns of East Africa.

By the ninth century a string of dynastic states, including the earliest Hausa states, stretched across the sub-Saharan savanna from the western regions to central Sudan. The most powerful of these states were Ghana, Gao, and the Kanem-Bornu Empire. Ghana declined in the 11th century and was succeeded by the Mali Empire, which consolidated much of western Sudan in the 13th century. Kanem accepted Islam in the 11th century.

In the forested regions of the West African coast, independent kingdoms such as the Nri Kingdom of the Igbo grew up with little influence from the Muslim north. The Ife, historically the first of the Yoruba city-states or kingdoms, established government under a priestly oba (“king”).

The Almoravids were a Berber dynasty from the Sahara that spread over a wide area of northwestern Africa and the Iberian peninsula during the 11th century. The Banu Hilal and Banu Ma’qil were a collection of Arab Bedouin tribes from the Arabian Peninsula who migrated westwards via Egypt between the 11th and 13th centuries. Following the breakup of Mali, the Songhai Empire was founded in middle Niger and the western Sudan. Its leader Sonni Ali and his successor Askia Mohammad I (1493–1528) made Islam the official religion, built mosques , and brought scholars to Gao Muslim.

Slavery had long been practiced in Africa. Between the seventh and 20th centuries, the Arab slave trade took 18 million slaves via the Trans-Saharan and Indian Ocean routes. Between the 15th and 19th centuries, the Atlantic slave trade took an estimated seven to 12 million slaves to the New World .

Ancient African Kingdoms and Empires: This map depicts a sample of the diverse cultures, kingdoms, and empires of pre-colonial Africa.

Form and MeaningQuestion 1: Do African artists lean more towards realism or abstraction? Why?

Headdress: Janus, 19th–20th century, Nigeria, Lower Cross River region, Ejagham or Bale people, Wood, hide, pigment, cane, horn, and nails, 53.3 x 43 x 25 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

While creations by African artists have been admired by Western viewers for their formal power and beauty, it is important to understand these artifacts on their own terms. Many African artworks were (and continue to be) created to serve a social, religious, or political function. In its original setting, an artifact may have different uses and embody a variety of meanings. These uses may change over time. A mask originally created for a particular performance may be used in a different context at a later time.

Abstraction and Idealization

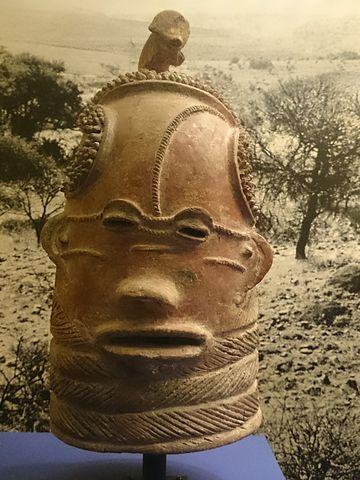

Helmet Mask, 19th-20th century, Sierra Leone, Moyamba region, Mende or Sherbro people, wood, metal, 47.9 x 22.2 x 23.5cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

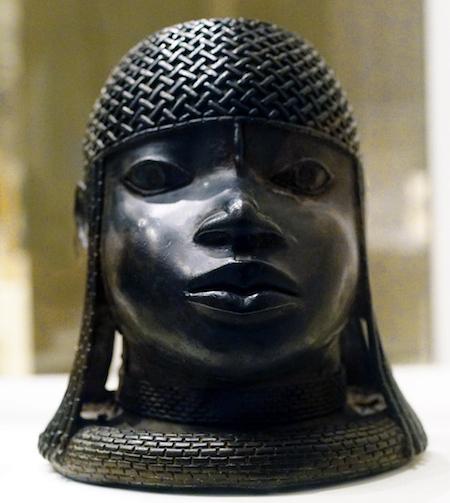

Realism or physical resemblance is generally not the goal of the African artist. Many forms of African art are characterized by their visual abstraction, or departure from representational accuracy. Artists interpret human or animal forms creatively through innovative form and composition. The degree of abstraction can range from idealized naturalism, as in the cast brass heads of Benin kings (above left), to more simplified, geometrically conceived forms, as in the Baga headdress (below).

Head of an Oba, Nigeria, Court of Benin, 16th century, brass, 23.5 x 21.9 c 22.9 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

The decision to create abstract representations is a conscious one, evidenced by the technical ability of African artists to create naturalistic art, as seen, for example, in the art of Ife, in present-day Nigeria. Idealization is frequently seen in representations of human beings. Individuals are almost always depicted in the prime of life, never in old age or poor health. Culturally accepted standards of moral character and physical beauty are expressed through formal emphasis.

Masks used by the women’s Sande society, for example, present Mende cultural ideals of female beauty (above right). Instead of a physical likeness, the artist highlights admired features, such as narrow eyes, a small mouth, carefully braided hair, and a ringed neck. Idealized images often relate to expected social roles and emphasize distinctions between male and female.

Art of Ancient AfricaThe art of ancient Africa is characterized by surviving sculptures, rock art, and architectural ruins.

African art constitutes one of the most diverse legacies on earth. Though many casual observers tend to generalize “traditional” African art, the continent consists of a breadth of people, societies, and civilizations , each with a unique visual culture. As the birthplace of the human species, Africa is the home of some of the oldest existing art forms. But because most were produced from wood and other highly perishable materials, few artworks produced before the 19th century survive. Examples include terra cotta sculptures, rock carvings, and architectural ruins.

The art of ancient African was just as diverse as its cultures, languages, and political structures. Most cultures preferred abstract and stylized forms of humans, plants, and animals, but they had a range of distinct approaches and techniques. Some cultures preferred more naturalistic depictions of human faces and other organic forms.

The Nubian Kingdom of Kush in modern Sudan was in close and often hostile contact with Egypt, and produced monumental sculpture mostly derivative of styles that did not spread to the north. In West Africa, the earliest known sculptures are from the Nok culture, which thrived between 500 BCE and 500 CE in modern Nigeria. These clay figures typically had elongated bodies and angular shapes.

Nok Rider and Horse, 53 cm tall (1,400 to 2,000 years ago): The Nok culture appeared in Nigeria around 1000 BCE and vanished under unknown circumstances around 500 CE in the region of West Africa, in modern Northern and Central Nigeria. Scholars think its social system was highly advanced. The Nok culture was the earliest sub-Saharan producer of life-sized terra cotta.

Human and Animal FormsThe human figure has always been a primary subject of African art, and this emphasis even influenced certain European traditions. For example, in the 15th century, Portugal traded with the Sapi culture near Côte d’Ivoire in West Africa, whose residents created elaborate ivory saltcellars that were hybrids of African and European designs. This was most notable in the addition of the human figure, which typically did not appear in Portuguese saltcellars. European subjects can be distinguished by their clothing and hairstyles. The human figure might symbolize the living or the dead. Possible subjects include chiefs, dancers, drummers, or hunters. They might be anthropomorphic representations of gods or ancestors or even have votive functions.

Saltcellar, 16th Century: Saltcellar by an Edo or Yoruba artist representing a Portuguese man decorated with horses among geometric patterns.

Even before contact with the Europeans, some African cultures opted for naturalistic depictions over the dominant preference for abstraction and stylization. This can be seen in the Yoruba portrait bronzes of Ile-Ife, which include indented and incised details that might represent ritual scarification .

Yoruba head: Bronze. Ile-Ife. Twelfth century.

The bronzes of Igbo-Ukwu pay special attention to detail depicting birds, snails, chameleons, and other natural aspects of the world. The objects are so fine that small insects were included on some surfaces. Each bronzes was produced in one piece.

Ceremonial vessel: Bronze. Igbo-Ukwu. Ninth century.

Sculpture of the Sub-Saharan CivilizationsQuestion 2: Compare the ancient terra cotta sculptures from the Nok culture in Nigeria to those found near present-day Lydenburg, South Africa

Sculpture of the NokTwo of the best examples of ancient terra cotta sculptures are from the Nok culture in Nigeria and from an ancient culture who lived near modern Lydenburg, South Africa.

The earliest identified Nigerian culture is the Nok culture, which thrived between 1500 BCE and 200 CE on the Jos Plateau in northeastern Nigeria. Information is lacking from the first millennium BCE following the Nok ascendancy. However, by the second millennium BCE, active trade routes had developed from Ancient Egypt via Nubia through the Sahara to the forest. Savanna peoples acted as intermediaries in exchanges of various goods. Reasons for the Nok’s sudden disappearance remains unknown.

Nok and Lydenburg Terra Cotta SculpturesAncient terra cotta sculptures in the form of human bodies or heads have been found in several areas of sub-Saharan Africa, providing glimpses into the cultures that existed in the region. Two of the best examples are from the Nok culture in present-day Nigeria and from an ancient culture living near the present-day town of Lydenburg, South Africa.

NokSimilarities in artwork suggest the Nok culture evolved into the later Yoruba culture of Ife. One example is this sculpture of a woman, which bears a striking resemblance to an early 20th-century sculpture of a king and queen mother by the Yoruba artist Olowe of Ise. The Nok culture was the earliest sub-Saharan producer of life-sized terra cotta sculptures.

Female figurine: Terra cotta. 48 cm tall. Nok culture. c. 515-1215 CE.

The first scattered fragments were discovered on the Jos Plateau during a tin mining expedition in 1928. The terra cotta figures are hollow, and while some include plant and animal motifs , the most well-known are of human heads and bodies that often reach life-sized proportions. These human sculptures contain very detailed and stylized features, abundant jewelry, and varied postures. Some even illustrate physical ailments, disease, or facial paralysis. While their function is largely unknown, theories include use as ancestor portrayal, grave markers, finials for roofs of buildings, or charms to protect against crop failure, infertility, or illness.

Nok Sculpture: Nok sculptures may have been used as grave markers, charms, or portrayals of ancestors. Terra cotta. Sixth century BCE-sixth century CE. Nigeria.

Researchers suggest that Nok ceramics were likely shaped by hand from coarse-grained clay and then sculpted with a technique similar to wood carving. After drying, the sculptures were covered with slip and polished to produce a smooth, glossy surface. The firing process probably resembled that used today in Nigeria, in which the sculptures are covered with grass, twigs, and leaves and burned for several hours.

LydenburgLydenburg, a town in Mpumalanga, South Africa, is also known for the discovery of some of the earliest forms of African sculpture. The Lydenburg Heads (400-500 CE) are terra cotta sculptures similar to those of the Nok. Found in the area in the late 1950s, their function is still unknown, although they likely served a ritualistic purposes as masks, ornamentation, or part of ceremonial regalia.

Lyndenburg Head: The Lydenburg Heads are the earliest known examples of African sculpture in Southern Africa. Two of the heads are large enough to have been ceremonial helmet masks. The five smaller heads have a hole on either side of the neck, by which they could have been attached to a pole or costume during a performance. One of the small heads has an animal-like nose and mouth, which would have been of symbolic importance to the makers of the heads.

Since their discovery, these heads have come to symbolize African art and won multiple awards. The image of the Lydenburg head can be seen both on the badge given by the South African Order of Ikhamanga representing achievement in the arts and in the Golden Horn trophy of the South African Film and Television Awards, which signifies excellence in visual creative arts, performance, and drama.

The Order of Ikhamanga: An image of the Order of Ikhamanga, where the Lydenburg head can be seen in the center.

Ile-Ife and Benin SculptureQuestion 3: Describe the characteristics of Ile-Ife and Benin sculpture.

Question 4: Describe the influence Portuguese culture had on Benin art.

Question 5: Why is ivory such an important commodity in Benin culture?

The Yoruba and Benin cultures produced bronze and ivory sculptures in modern Nigeria from the 13th through the 19th centuries.

YorubaIfe is the home to the Yoruba people of southwestern Nigeria, located in the present-day Osun State. The Yoruba people comprise one of the largest ethnic groups in Sub-Saharan Africa, constituting close to 40 million people predominantly in Nigeria. Evidence of habitation at the site dates to as early as 600 BCE. Some evidence suggests the Yoruba developed from the Nok culture (1000 BCE–500 CE).

The meaning of the word “ife” in Yoruba is “expansion.” According to Yoruba faith, the city of Ife is where all of humanity originated: Oduduwa created the world where Ife would be built, and his brother Obatala created the first humans out of clay. The city was a settlement of substantial size between the ninth and 12th centuries CE. Production of Yoruba artwork reached its peak between 1200 and 1400 CE, after which it declined as political and economic power shifted to the nearby kingdom of Benin.

Artwork of IfeIfe is best known for its naturalistic bronze sculptures. Hollow-cast bronze art created by the Yoruba culture provides an example of realism in precolonial African art. Important people were often depicted with large heads, as the Yoruba believed that the Ase, or inner power and energy of a person, resided in the head. Their rulers were often depicted with their mouths covered so that the power of their speech would not be too great .

Ife Bronze Sculpture: Sculpture of a king’s head, held in the British Museum.

Stone and terra cotta artwork were also common in Ife. More elaborate festivals organized to worship deities were also common. These would often extend over several days and involve theatrical dramatizations in the palace and kingdom.

In his book “The Oral Traditions in Ile-Ife,” Yemi D. Prince referred to the terra cotta artists of 900 CE as the founders of art guilds , cultural schools of philosophy similar to Europe’s old institutions of learning. These guilds may be some of the oldest non-Abrahamic African centers of learning still in existence.

BeninThe Benin Empire was a precolonial African kingdom that ruled Nigeria from the eleventh century to 1897. Not to be confused with the present-day country of Benin, this empire dissolved into what is today the Edo State of Nigeria, marked by the capital , Benin City. At its height, the empire developed an advanced artistic culture and produced beautiful artifacts of bronze, iron and ivory .

Art of BeninThe Benin Empire was known for its many works of art, including religious objects, ceremonial weapons, masks, animal heads, figurines , busts, and plaques. Typically made from bronze, brass, clay, ivory, terra cotta, or wood, most pieces were produced at the court of the Oba (king) and used to illustrate achievements of the empire or narrate mythical stories. Iconic imagery depicted religious, social, and cultural issues central to their beliefs, and many bronze plaques featured representations of the Oba.

Various works promoted theological and religious piety, while others narrated past events and achievements (actual or mythical). During the reign of the Kingdom of Benin, the characteristics of the artwork shifted from thin castings and careful treatment to thick, less defined castings and generalized features.

Sculpture of the Benin Kingdom: This sculpture, one of the many examples of Benin Bronzes held in museums around the world, depicts the generalized figures that frequently appear in Benin art. 16th-18th century. Nigeria.

One of the most common artifacts today is the ivory mask based on Queen Idia, the mother of Oba Esigie who ruled from 1504-1550. Now commonly known as the Festac mask, it was used in 1977 as the logo of the Nigeria-hosted Second Festival of Black & African Arts and Culture.

Pendant ivory mask of Queen Idia: Iyoba ne Esigie (meaning: Queen mother of Oba Esigie), court of Benin, 16th century.

This pendant mask was created in the early sixteenth century for an Oba named Esigie, in honor of his mother Idia. The face has softly modeled, naturalistic features, with graceful curves that echo the oval shape of the head. Four carved scarification marks, a number associated with females, indicate her gender.

Iron inlays for the pupils and rims of the eyes intensify the Queen Mother’s authoritative gaze and suggest her inner strength. The two vertical depressions on her forehead were also inlaid with iron. She is depicted wearing a choker of coral beads and her hair is arranged in an elegant configuration that resembles a tiara. The intricately carved openwork designs are stylized mudfish alternating with the faces of Portuguese traders. Both motifs are associated with the Oba and his counterpart, the sea god Olokun. The mudfish is a creature that lives both on land and in water, and a symbol of the king’s dual nature as both human and divine. Similarly, the Portuguese, as voyagers from across the sea, may have been seen as denizens of Olokun’s realm. Like the sea god, they brought great wealth and power to the Oba.

In Benin culture, ivory holds both material and symbolic value. As a luxury good, ivory was Benin’s principal commercial commodity and helped to attract Portuguese traders who, in turn, brought wealth to the kingdom in the form of copper and coral. In addition, ivory is white, a color that symbolizes ritual purity and is also associated with Olokun, who is considered to be a source of extraordinary wealth and fertility.

Queen Idia is honored as a powerful and politically astute woman who provided critical assistance to her son during the kingdom’s battles to expand. Upon the successful conclusion of the war, Esigie paid tribute to Idia by bestowing upon her the title of Queen Mother, a custom that has continued with subsequent rulers until the present time. The title of Queen Mother, or Iyoba, is given to the woman who bears the Oba’s first son, the future ruler of the kingdom. Historically, the Queen Mother would have no other children and, instead, devote her life to raising her son. Oba Esigie is said to have worn the mask as a pectoral during rites commemorating his mother. The hollow back, holes around the perimeter, and stopper composed of several tendrils of hair at the summit suggest that the mask functioned as an amulet, filled with special and powerful materials that protected the wearer. Today, such pendants are worn at annual ceremonies of spiritual renewal and purification.

Portuguese InfluenceThe peak of the Benin art occurred in the fifteenth century with the arrival of the Portuguese missionaries and traders. By that point, Benin was already highly militarized and economically developed. However, the arrival of the Portuguese catalyzed a process of even greater political and artistic development.

Because of Benin’s military strength, Portuguese missionaries were unable to enslave its people upon their arrival in the fifteenth century. Instead, a trade network was established in which the Benin Empire traded beautiful works of art for luxury items from Portugal, such as beads, cloth, and brass manillas for casting. The wealth of Benin’s art was credited with preventing the empire from becoming economically dependent on the Portuguese.

As trade flourished, Benin art began to depict European influence through technique, imagery, and themes. Bronze work reached its height during this era, and today the Benin Bronzes are regarded as some of the finest works of that time. These depict a variety of scenes including animals, court life, Portuguese sailors, and relationships between the Benin Empire and the Portuguese. They were cast in matching pairs (although each was individually made), and may have originally been nailed to walls and pillars in the palace as decoration.

Benin plaque: The background portrays the floral pattern characteristic of plaques made at this time and reflective of Portuguese influence. The image in the plaque consists of an Oba (king) surrounded by his subjects. Apart from military and political strength, the plaque illustrates the relationship between the Portuguese and the Benin traders. 16th century.

In 1897, the British led the Punitive Expedition in which they ransacked the Benin kingdom and destroyed or confiscated much of their artwork. Over 3,000 brass plaques were seized and are now held in museums around the world.

In 1936, Oba Akenzua II began a movement to return the art to its place of origin. Nigeria bought approximately 50 bronzes from the British Museum between the 1950s and 1970s and has repeatedly called for the return of the remainder.

Sculpture of the Kingdom of KongoQuestion 6: Discuss the function of Kongolese nkisi and nkondi. What purpose did they serve? How were they used?

The Kingdom of Kongo was a highly developed state in the 13th century, best known for its nkisi (power objects).

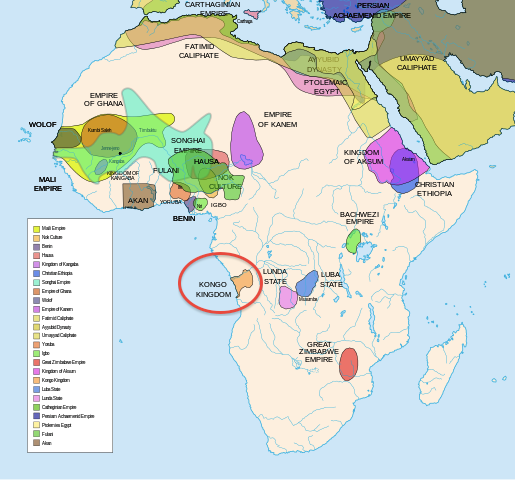

The Kingdom of the Kongo was an African kingdom located in west central Africa in what is now northern Angola, Cabinda, the western portion of the Democratic Republic of the Congo, and the southernmost part of Gabon. At its greatest extent, it reached from the Atlantic Ocean in the west to the Kwango River in the east, and from the Congo River in the north to the Kwanza River in the south.

Map of Precolonial Africa: The Kingdom of Kongo is circled in red.

The first king of the Kingdom was Lukeni lua Nimi (circa 1280-1320). By the time of the first recorded contact with the Europeans, the kingdom was a highly developed state at the center of an extensive trading network. Apart from natural resources and ivory, the country manufactured and traded copperware, ferrous metal goods, raffia cloth, and pottery. The eastern regions were particularly famous for cloth production.

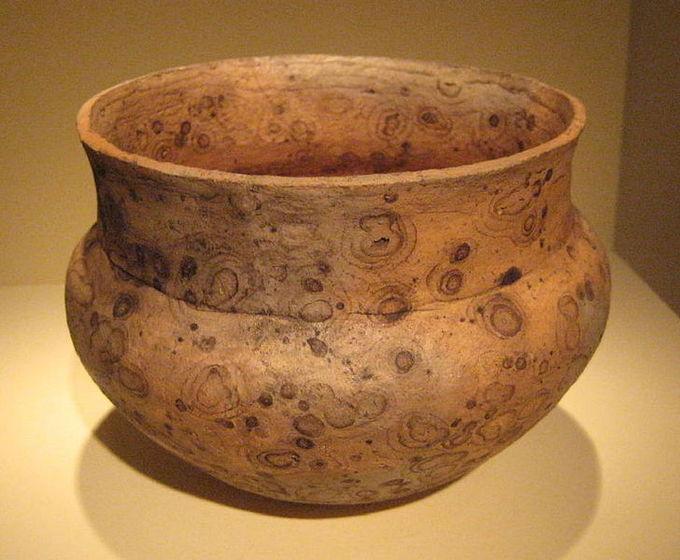

An example of Kongo pottery: Made of ceramic and vegetable dye, such pottery was widely manufactured in the Kingdom of Kongo.

Artistically, the Kingdom of Kongo is perhaps best known for its nkisi (singular: minkisi), objects believed to be inhabited by spirits. Early travelers often called nkisi “fetishes” or “idols,” as some were made in human form . Modern anthropology has generally called them either “power objects” or “charms.” As in many African cultures , the Kongo religion placed great importance on communication with ancestors, believing that exceptional human powers could result from this communication. Nkisi were containers such as ceramic vessels, gourds, animal horns, or shells, designed to hold spiritually charged substances. Sometimes considered “portable graves,” elements like earth or relics from the grave of a powerful individual were often placed in the bellies of nkisi. The powers of the dead thus infused the object, placing it under control of the ngaga (healer, diviner, or mediator).

Nkisi were often used in divination practices, for healing, or for good fortune in hunting, trade, or sex. Most famously, nkisi take the form of anthropomorphic or zoomorphic wooden carvings. Birds of prey, dogs (closely tied to the spiritual world in Kongo theology), lightning, weapons, and fire are all common themes. The substances chosen for inclusion in nkisi are frequently called “bilongo” or “milongo” (singular nlongo) a word often translated as “medicine.” However, their operation was not primarily pharmaceutical, as they were not applied to or ingested by the infirm. Rather, they were frequently chosen for metaphoric reasons, such as correcting illicit behavior.

Minkisi: The light area on the figure’s abdomen is a glass “window” that would hold “medicine” used for correcting illicit or immoral behavior.

Nkondi – often referred to as “nail fetishes” – are an aggressive type of nkisi that were thought to be activated by having nails driven into them. Each nail or metal piece represented a vow, a signed treaty, and efforts to abolish evil. Although nkisi nkondi have probably been made since at least the 16th century, the nailed figures were most likely made in the northern part of the Kongo in the 19th and early 20th centuries.

Female power figure of the Vili people – Democratic Republic of Congo: While this figure was made by the Vili people, it is similar to the nkisi nkondi made by people in the Kongo Kingdom.

The name nkondi derives from the verb -konda, meaning “to hunt” and thus nkondi means “hunter” because they can hunt down and attack evildoers or enemies. The object’s primary function is to house a spirit that can hunt down the source or sources of evil that threaten an individual or an entire village. While some nkondi figures appear relatively benign, like the example above, others assume more aggressive body language and facial expressions to demonstrate their ability to attack evildoers successfully.

Minkisi nkondi: This figure assumes a more aggressive facial expression and body language.

Some nkondi assume zoomorphic forms, such as this sculpture of a protective wild animal.

Detail of a zoomorphic nkondi: Wood, metal, and porcelain. Eighteenth-nineteenth century.

Art of West African CivilizationsQuestion 7: What is the difference between kente cloth among the Asante and Ewe peoples? Think about who could wear the cloth and under what circumstances.

Question 8: Are the colors and patterns on kente cloth coincidental? Or do they serve a purpose? Explain your answer.

Kente cloth (Asante and Ewe peoples)

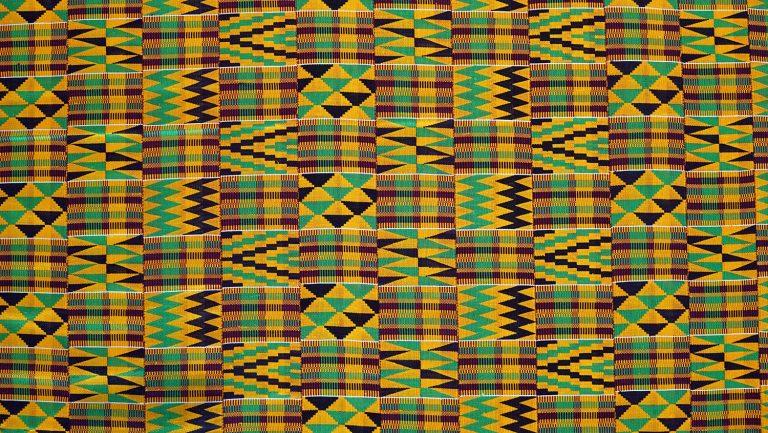

Asante kente cloth, 20th century, silk and cotton (Vatican Museums)

Inspired by a spider’s webAmong the Asante (or Ashanti) people of Ghana, West Africa, a popular legend relates how two young men—Ota Karaban and his friend Kwaku Ameyaw—learned the art of weaving by observing a spider weaving its web. One night, the two went out into the forest to check their traps, and they were amazed by a beautiful spider’s web whose many unique designs sparkled in the moonlight. The spider, named Ananse, offered to show the men how to weave such designs in exchange for a few favors. After completing the favors and learning how to weave the designs with a single thread, the men returned home to Bonwire (Bonwire is the town in the Asante region of Ghana where kente weaving originated), and their discovery was soon reported to Asantehene Osei Tutu, first ruler of the Asante kingdom. The asantehene adopted their creation, named kente, as a royal cloth reserved for special occasions, and Bonwire became the leading kente weaving center for the asantehene and his court.

Asantehene Osei Tutu II wearing kente cloth, 2005 (photo: Retlaw Snellac, CC BY 2.0)

A royal clothOriginally, the use of kente was reserved for Asante royalty and limited to special social and sacred functions. Even as production has increased and kente has become more accessible to those outside the royal court, it continues to be associated with wealth, high social status, and cultural sophistication. Kente is also found in Asante shrines to the deities, or abosom, as a mark of their spiritual power.

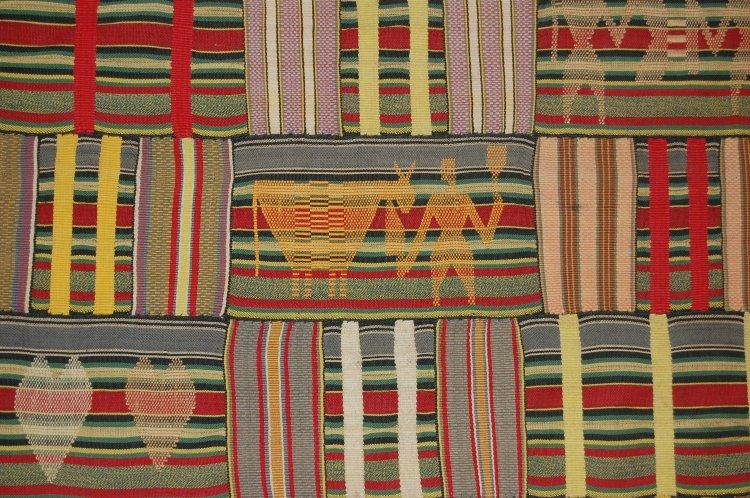

Ewe kente cloth (detail), 1920-40, Ghana, cotton, 339 x 198 cm (The British Museum)

Historians maintain that kente cloth grew out of various weaving traditions that existed in West Africa prior to the formation of the Asante Kingdom. These techniques were appropriated through vast trade networks, as were materials such as French and Italian silk, which became increasingly desired in the 18th century and were combined with cotton and wool to make kente.

Kente cloth is also worn by the Ewe people, who were under the rule of the Asante kingdom in the late 18th century. It is believed that the Ewe, who had a previous tradition of horizontal loom weaving, adopted the style of kente cloth production from the Asante—with some important differences. Since the Ewe were not centralized, kente was not limited to use by royalty, though the cloth was still associated with prestige and special occasions. A greater variety in the patterns and functions exist in Ewe kente, and the symbolism of the patterns often has more to do with daily life than with social standing or wealth.

Weaving kenteKente is woven on a horizontal strip loom, which produces a narrow band of cloth about four inches wide. Several of these strips are carefully arranged and hand-sewn together to create a cloth of the desired size. Most kente weavers are men.

Weaving involves the crossing of a row of parallel threads called the warp (threads running vertically) with another row called the weft (threads running horizontally). A horizontal loom, constructed with wood, consists of a set of two, four or six heddles (loops for holding thread), which are used for separating and guiding the warp threads. These are attached to treadles (foot pedals) with pulleys that have spools of thread inserted in them. The pulleys can be used to move the warp threads apart. As the weaver divides the warp threads, he uses a shuttle (a small wooden device carrying a bobbin, or small spool of thread) to insert the weft threads between them. These various parts of the loom, like the motifs in the cloth, all have symbolic significance and are accorded a great deal of respect.

Kente weaver in Adanwomase village, Ashanti Region, Ghana (photo: Shawn Zamechek, CC BY 2.0)

By alternating colors in the warp and weft, a weaver can create complex patterns, which in kente cloth are valued for both their visual effect and their symbolism. Patterns can exist vertically (in the warp), or horizontally (in the weft), or both.

A cloth with a namePatterns each have a name, as does each cloth in its entirety. Names are sometimes given by weavers who obtain them through dreams or during contemplative moments when they are said to be in communion with the spiritual world. Alternatively, chiefs and elders may ascribe names to cloths that they specially commission. Names can be inspired by historical events, proverbs, philosophical concepts, oral literature, moral values, human and animal behavior, individual achievements, or even individuals in pop culture. In the past, when purchasing a cloth, the aesthetic and social appeal of the cloth’s was as important as—or sometimes even more important than—its visual pattern or color.

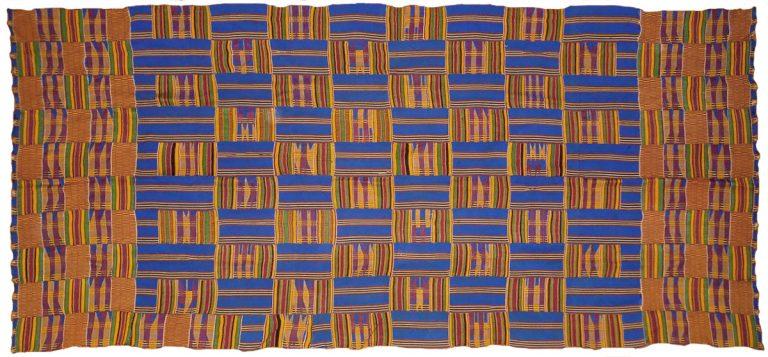

The King has Boarded the Ship (Asante kente cloth), c. 1985, rayon (collection of Dr. Courtnay Micots)

This cloth is named The King Has Boarded the Ship, and it includes both warp and weft patterns. The warp pattern, consisting of two multicolor stripes on blue, relates to the proverb “Fie buo yE buna,” meaning the head of the family has a difficult task. The weft patterns vary throughout the cloth; these examples are “NkyEmfrE,” a broken pot, and “Kwadum Asa,” an empty gunpowder keg.

The King has Boarded the Ship (details), left: “Broken Pot” pattern; right: “Empty Powder Keg” pattern, c. 1985, rayon (collection of Dr. Courtnay Micots)

Wearing kenteThere are differences in how the cloth is worn by men and women. On average, a men’s size cloth measures 24 strips wide, making it about 8 feet wide and 12 feet long. Men usually wear one piece wrapped around the body, leaving the right shoulder and hand uncovered, in a toga-like style. Women may wear either one large piece or a combination of two or three pieces of varying sizes ranging from 5-12 strips, averaging of 6 feet long. Age, marital status, and social standing may determine the size and design of the cloth an individual would wear.

Men (left) and women (right) wearing kente at the Kente Cloth Festival in Kpetoe, September 2005 (photos: John Nash, CC BY-NC 2.0)

Social changes and modern living have brought about significant changes in how kente is used. It is no longer only the privilege of royalty; anyone who can afford it can buy kente. The old tradition of not cutting the cloth has also long been set aside, and it may be sewn into other forms such as dresses, shirts, or shoes. Printed versions of kente are mass produced and marketed, and both woven and printed versions are used by fashion designers in Ghana and abroad.

Kente print bag, 1990s (photo: Huzzah Vintage, CC BY-NC 2.0)

Kente is more than just a cloth. It is an iconic visual representation of the history, philosophy, ethics, oral literature, religious belief, social values, and political thought of West Africa. Kente is exported as one of the key symbols of African heritage and pride in African ancestry throughout the diaspora. In spite of the proliferation of both the hand-woven and machine-printed kente, the design is still regarded as a symbol of social prestige, nobility, and cultural sophistication.

Architecture of the Sub-Saharan CivilizationsQuestion 9: What are the main structures in the complex of Great Zimbabwe? What function do we think they served and how can we tell?

Question 10: What indications do we have that Great Zimbabwe was the home of many powerful and wealthy individuals?

Architecture of Great ZimbabwePerhaps the most famous site in southern Africa, Great Zimbabwe is a ruined civilization constructed by the Mwenemutapa. A monumental city built of stone, it is one of the oldest and largest structures in southern Africa. Located about 150 miles from the modern Zimbabwean capital of Harare, Great Zimbabwe was the capital of a medieval kingdom that occupied the region on the eastern edge of Kalahari Desert.

Development of Great ZimbabweAs there are no written records from the people who inhabited Great Zimbabwe, knowledge of the culture is dependent on archaeology. Small farming and iron-mining communities began to appear in the area between the fourth and seventh centuries CE. Most were cattle pastoralists , but the discovery of gold and new mining techniques contributed to a rise in trade with caravan merchants to the north. As local leaders became rich from trade, they grew in power and created the centralized city-state of Great Zimbabwe.

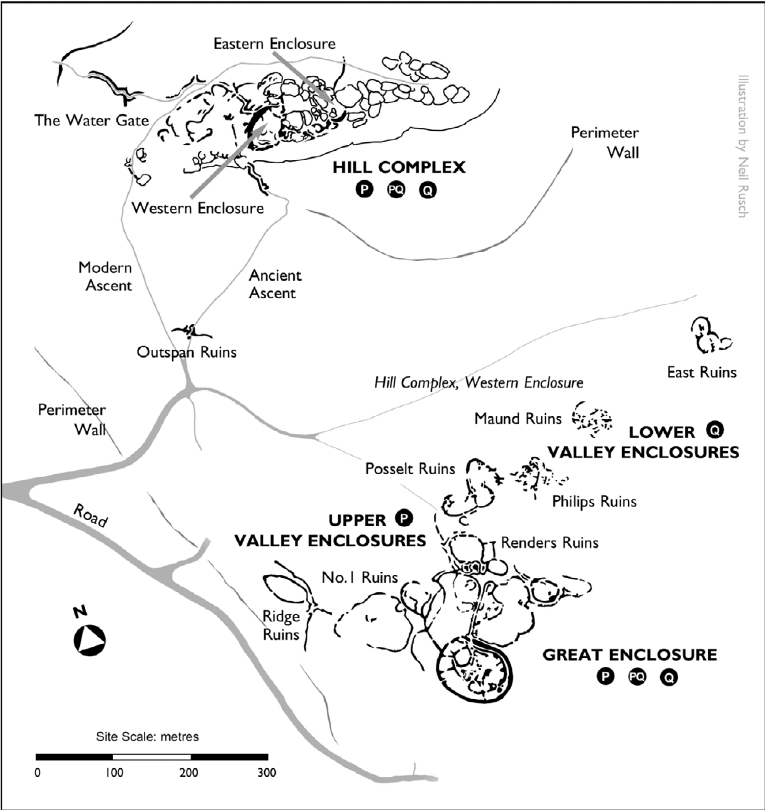

Monument ConstructionConstruction of the monument began in the 11th century and continued through the fourteenth century, spanning an area of 1,780 acres and covering a radius of 100 to 200 miles. At its peak, it could have housed up to 18,000 people. The load-bearing walls of its structures were built using granite with no mortar, evidence of highly skilled masonry. The ruins form three distinct architectural groups known as the Hill Complex (occupied from the ninth through 13th centuries), the Great Enclosure (occupied from the 13th through 15th centuries), and the Valley Complex (occupied from the 14th through 16th centuries).

One of the most prominent features of Great Zimbabwe was its walls, some of which reached 11 meters high and extended approximately 820 feet.

Close-up of Great Zimbabwe: Great Zimbabwe is most famous for its enormous walls, built without mortar.

The stone constructions of Great Zimbabwe can be categorized into roughly three areas: the Hill Ruin (on a rocky hilltop), the Great Enclosure, and the Valley Ruins (map below). The Hill Ruin dates to approximately 1250, and incorporates a cave that remains a sacred site for the Shona peoples today. The cave once accommodated the residence of the ruler and his immediate family. The Hill Ruin also held a structure surrounded by 30-foot high walls and flanked by cylindrical towers and monoliths carved with elaborate geometric patterns.

The Great Enclosure was completed in approximately 1450, and it too is a walled structure punctuated with turrets and monoliths, emulating the form of the earlier Hill Ruin. The massive outer wall is 32 feet high in some places. Inside the Great Enclosure, a smaller wall parallels the exterior wall creating a tight passageway leading to large towers. Because the Great Enclosure shares many structural similarities with the Hill Ruin, one interpretation suggests that the Great Enclosure was built to accommodate a surplus population and its religious and administrative activities. Another theory posits that the Great Enclosure may have functioned as a site for religious rituals.

Between two walls, Great Enclosure, Great Zimbabwe (photo: Mandy, CC BY 2.0)

The third section of Great Zimbabwe, the Valley Ruins, include a number of structures that offer evidence that the site served as a hub for commercial exchange and long distance trade. Archaeologists have found porcelain fragments originating from China, beads crafted in southeast Asia, and copper ingots from trading centers along the Zambezi River and from Central African kingdoms.[2]

A monolithic soapstone sculpture of a seated bird resting on atop a register of zigzags was unearthed here. The pronounced muscularity of the bird’s breast and its defined talons suggest that this represents a bird of prey, and scholars have conjectured it could have been emblematic of the power of Shona kings as benefactors to their people and intercessors with their ancestors.

Conical Tower, Great Zimbabwe (photo: Mandy, CC BY 2.0)

Conical towerAll of the walls at Great Zimbabwe were constructed from granite hewn locally. While some theories suggest that the granite enclosures were built for defense, these walls likely had no military function. Many segments within the walls have gaps, interrupted arcs or elements that seem to run counter to needs of protection. The fact that the structures were built without the use of mortar to bind the stones together supports speculation that the site was not, in fact, intended for defense. Nevertheless, these enclosures symbolize the power and prestige of the rulers of Great Zimbabwe.

The conical tower (above) of Great Zimbabwe is thought to have functioned as a granary. According to tradition, a Shona ruler shows his largess towards his subjects through his granary, often distributing grain as a symbol of his protection. Indeed, advancements in agricultural cultivation among Bantu-speaking peoples in sub-Saharan Africa transformed the pattern of life for many, including the Shona communities of present-day Zimbabwe.

The Conical Tower: The Conical Tower is 18 feet (5.5 meters) in diameter and 30 feet (9.1 meters) high.

One theory suggests that the complexes were the work of successive kings. Perhaps the focus of power moved from the Hill Complex to the Great Enclosure in the 12th century, then to the Upper Valley, and finally to the Lower Valley in the early 16h century. A more structuralist interpretation holds that the different complexes had different functions. For example the Hill Complex was a temple, the Valley Complex was built for the citizens, and the Great Enclosure was used by the king.

Cultural Aspects of Great ZimbabweGreat Zimbabwe shows a high degree of social stratification, characteristic for centralized states. For the elite, there seems to have been a great deal of wealth. Plentiful pottery, iron tools, copper and gold jewelry, elaborately worked ivory , bronze spearheads, gold beads and pendants, and soapstone sculptures have all been found at the site. Some of the artifacts, such as ceramics and glass vessels , appear to have come from Arabia, India, and even China, suggesting that Great Zimbabwe was a major trade center. Smaller stone settlements called zimbabwes can be found nearby. These are thought to be seats of authority for local governors acting under the king of Great Zimbabwe. These smaller settlements would have been supported by surrounding farmers.

Great Zimbabwe was abandoned by 1500, possibly due to land exhaustion, drought, famine , or a decline in trade. Zimbabwean culture would continue in Mutapa, centered on the city of Sofala. The site of Great Zimbabwe is considered a source of pride in the region, and the modern nation of Zimbabwe derived its name from the site. Nonetheless, when European colonizers first found the ruins in the late 19th century, most did not believe that the site could have been built by indigenous Africans. In fact, political pressure was put on historians and architects to deny its construction by black people until Zimbabwe’s independence in the 1960s.