Strategic Management - 5-page (maximum) paper. The paper should contain the following: 1. A 1+ page discussion describing disruptive business models. You should use examples of companies that have int

![]()

WHAT BUSINESS IS ZARA IN? (REVISED)1

Daniel J. Doiron wrote this case solely to provide material for class discussion. The author does not intend to illustrate either effective or ineffective handling of a managerial situation. The author may have disguised certain names and other identifying information to protect confidentiality.

This publication may not be transmitted, photocopied, digitized, or otherwise reproduced in any form or by any means without the permission of the copyright holder. Reproduction of this material is not covered under authorization by any reproduction rights organization. To order copies or request permission to reproduce materials, contact Ivey Publishing, Ivey Business School, Western University, London, Ontario, Canada, N6G 0N1; (t) 519.661.3208; (e) [email protected]; www.iveycases.com. Our goal is to publish materials of the highest quality; submit any errata to [email protected].

Copyright © 2019, Ivey Business School Foundation Version: 2019-04-09

What would 2019 have in store for Industria de Diseño Textil, SA (Inditex) and its flagship brand Zara with its “fast fashion” business model? It had taken years for both old and new competitors to build and enhance their business approach to effectively compete with Zara’s model,2 while online shopping for fashion apparel was on the rise.

Many recalled the early deference people had had towards Zara and its counter-intuitive business model. Why would anyone invest in a fashion manufacturer and retailer that produced its clothing in the high-cost labour market of Spain (versus Asia); spent very little on advertising; ostensibly overspent on positioning high-end stores in chic retail districts across Europe; carried substantially less inventory than its competitors; manufactured clothes that were, arguably, of a lesser quality; and, finally, charged 15 per cent less at the cash register? By all accounts, this approach was viewed as a formula for disaster in the highly competitive retail fashion industry.3

During those early years, most observers were just not forward thinking enough to see the value in Zara’s approach—and over time, Inditex took great pride in proving them wrong. By 2014, Zara was by far the number-one fashion retailer in the world by many measures,4 and it continued to maintain this leadership position in 2019. Its unique business model had enabled this astounding success.

Inditex, however, could not dwell on past successes, as the future was full of significant challenges associated with the many new upstart and copycat competitors that had infiltrated the market. It was highly likely that these new firms would also enjoy a reasonable degree of success. Disruptive innovations, such as Zara’s business model, inevitably were copied. Examples of companies’ disruptive business models leading to significant change in their industries included Southwest Airlines Co. leading the discount airline industry, Walmart Inc. dominating the discount department store industry, and perhaps Google’s leadership in its Waymo self-driving technology ride sharing services.

Perhaps it was time for Inditex to reinvent the industry business model, once again.

THE EARLY YEARS

In 1963, when Amancio Ortega Gaona started his small dressmaking firm in La Coruña, Spain, at the tender age of 16,5 he never dreamed it would lead to the world’s largest retail fashion empire. Nor did he aspire to become the fourth-richest person in the world.6 What he did come to understand over the next 12 years was

that textile manufacturing was a very risky, often frustrating business when you were one step removed from your customers. This was especially true in the fast-changing women’s fashion segment of the market. So in 1975, when he opened his first Zara store in the centre of La Coruña, a town of 246,000 people, he was driven by the overriding principle that the key to success as a fashion retailer was to link fashion design to manufacturing and distribution in a way that allowed for rapid responses to the finicky and often changing needs of customers. This was the sole foundation for the creation and growth of Zara, and it remained central to its success. This early success spurred the opening of nine new stores in Spain’s largest cities over the next eight years.7

Ortega also learned that to be successful he would have to take advantage of the intelligence of the employees throughout his company and trust their judgment.8 In other words, a top-down decision-making model, as it related to new product design and distribution, would be counterproductive to his overriding notion of reacting quickly to customers’ needs. Thus, he put decisions related to the critical processes of product design, manufacturing, and distribution into the hands of his employees across the company.

The combined approach of manufacturing new clothing as quickly as possible in response to customers’ needs and desires while adopting a decentralized decision-making process allowed Zara to thrive and grow in the ultra-competitive retail fashion industry. Over the 17 years following the launch of Zara in 1975, Ortega opened more than 1,000 new stores, culminating in an initial public offering on May 23, 2001. The funds raised through this offering provided the fuel for a tremendous evolution that saw Inditex grow to operate 7,475 stores in 96 markets across eight brands, propelling it to fiscal 2017 revenue of €25.3 billion9 and industry-leading gross profit margins of 57.4 per cent (see Exhibit 1).10 This represented an astounding compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 10 per cent over the period 2012–2017.11 Inditex was by far the world’s largest fashion manufacturing and retail business.

THE GLOBAL FASHION RETAIL INDUSTRY

The global retail fashion industry was worth US$2.5 trillion in 2017,12 employing approximately 75 million people. The industry was expected to grow at a rate of 4–5 per cent from 2018 to 2019.13

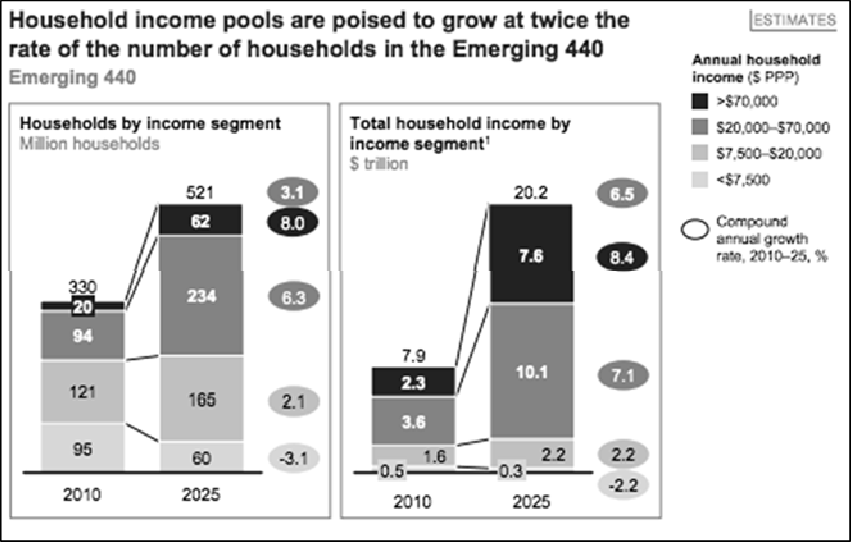

The industry was influenced by a number of factors, including changing demographics and the urbanization of the global population. A full 60 per cent of the global population would be living in cities by 2025,14 up from 45 per cent in 2011. Likewise, Europe would see 82.2 per cent of its population living in urban centres, while in North America, this figure was 88.6 per cent.15 According to a McKinsey & Company report on succeeding in the future fashion market, “By 2020, a quarter of global wealth will be concentrated in just 60 mega-cities, some of which will be larger than countries,” with 16 of the 20 fastest growing cites for fashion apparel in emerging markets.16With the global population predicted to grow to 8.2 billion by 2030 from 7 billion in 2014,17 it would seem the industry was on a trajectory for continued strong growth. This, tied to a growing middle class in developing nations such as China and India, could lead to a substantive increase in spending on fashion clothing; in fact, China was expected to surpass the United States as the world’s top fashion retail market in 2019. By 2030, East Asia’s middle class was expected to number over 3 billion, up from the current 1.5 billion. Spending by the middle class was projected to rise from $21 trillion today to $51 trillion in 2030.18 This would surely fuel the retail fashion apparel industry for years to come (see Exhibit 2).

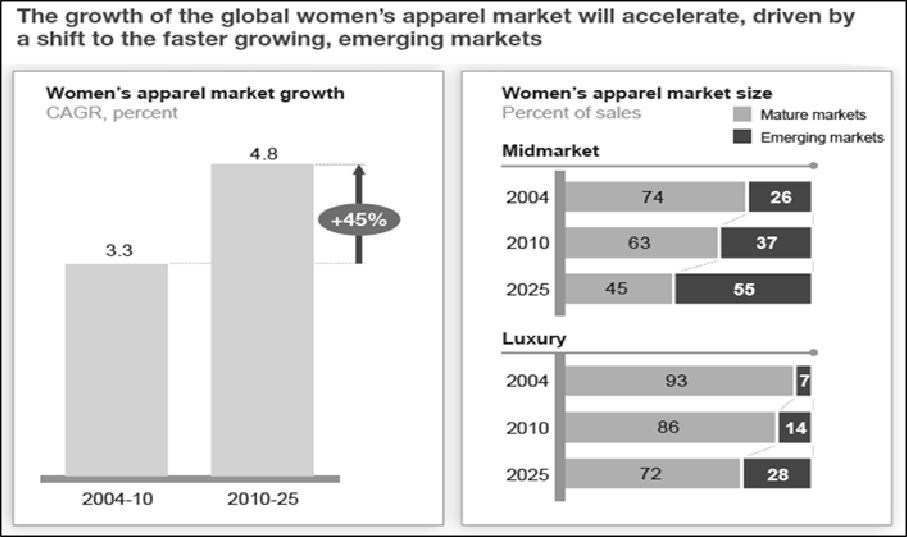

The global women’s apparel market was predicted to grow by 4.8 per cent annually from 2010 to 2025, outpacing the previous growth of 3.3 per cent for the six years prior.19Though, as Lu et al. stated, “Some 80 per cent of top growth cities for total apparel sales by 2025 will be in emerging markets,” leaving growth to lag in developed countries. The authors went on to say that these cities would enlarge the world apparel markets by an additional $100 billion over this period.20Emerging markets at that time would represent 55 per cent of mid-market women’s apparel sales (see Exhibit 3).

The trends and challenges in this market were many. Responsible sourcing, including greater visibility across the entire supply chain, topped the list. Tragic events, such as the blaze at the Tazreen garment factory in Bangladesh in November 2012,21 had heightened the need for textile manufacturers and retailers to strengthen their supply chains to ensure fair trade, safe work environments, living wages, social commitment, and responsible resource development.

Industry growth opportunities, specifically in developed countries, were being led by the plus-size categories. This was a $17.5 billion market in the 12 months ending April 2014 in the United States, up 5 per cent over the previous year, and a direct reflection of the obesity epidemic underway in the developed world, where seven of 10 Americans were now overweight.22 The plus-size market opportunity in the United States was estimated at $46 billion. In the United Kingdom, the plus-size market was predicted to grow at a CAGR of 7.1 per cent through 2022.23

Digital adoption by mainstream consumers, with online sales of apparel, was forecast to grow rapidly, outpacing market growth projections. In 2017, McKinsey & Company predicted a 10 per cent CAGR for online apparel and footwear through 2020. In 2017, in the United States alone, online sales accounted for

27.4 per cent of overall apparel sales, up from 20.7 per cent in 2015, with women’s apparel trailing but still expected to represent 24 per cent of sales by 2021.24

Another factor affecting the industry was global transport costs, which were linked to the price of oil. It would seem that with oil prices near or below $60 per barrel since 2014, these costs would likely continue on a downward swing. Technological innovation in textile manufacturing was affecting important metrics within the industry beyond cost reduction. Mass customization, small-batch manufacturing, and time to market were becoming key risk management factors. These drove a deeper focus across the entire supply chain. In 2017, “fast fashion” retailers, like Inditex, H&M, Forever 21 Inc., and Primark Stores Ltd., saw their sales grow by 8.2 per cent in aggregate, against an industry growth rate of 3.5 per cent.25 New fabric innovation was also having a strong positive impact on the growth of the apparel industry, specifically in the sportswear market.

Commodity prices could significantly impact the industry cost structure, specifically the price of cotton, which represented 24.5 per cent of the total fibre market in 2016/2017 with production of 23 million metric tons.26 Global cotton prices hovered around 76 cents per pound and were likely to remain low against a backdrop of demand uncertainty, continuing U.S. trade wars, and the evolution of synthetics.27

Additionally, the rapidly growing population of consumers over 50, referred to as a “demographic earthquake” in developed countries, would become one of the fastest-growing segments to be considered in terms of its expenditures on clothing. By 2020, spending by this group globally was expected to grow to

$15 trillion, up from $8 trillion in 2010.28

CUSTOMER BEHAVIOURS

Perhaps the most significant factors driving change in the retail apparel industry were associated with shifting customer behaviours. Customer buying patterns and behaviours could directly influence a firm’s ability to succeed and in many cases determined both a firm’s approach and, indeed, the resulting industry business model. The urban retail fashion market, where Zara played,29 was inextricably tied to two key customer behaviours:

Unpredictability and Influence

Fashion apparel customers were a fickle group that could be extremely hard to predict and influence. They could be easily swayed by unpredictable factors, such as celebrity fashion, friends’ fashion choices, or the need to differentiate themselves in a crowded urban environment. These variables made it extremely challenging to predict the next fashion hit and contributed to the single largest risk in retail apparel: a “fashion miss.” In turn, fashion misses resulted in discounts and markdowns in order to make room for new inventory. For example, in its first quarter 2018 report, H&M reported $4.3 billion of what Pam Danziger of Unity Marketing called “unexciting, uninspired, unsold inventory,”30 most of which would have to be discounted. Studies showed that specialty apparel retailers could end up marking down 30–40 per cent of their inventory by up to 60 per cent on average.31To mitigate this risk, many apparel retailers spent an exorbitant amount of money on advertising, with a focus on building brand awareness and loyalty. And it worked—to a degree. For example, in 2017, Gap Inc. (Gap) spent $673 million on advertising, a 12 per cent year-over-year growth, representing 4.2 per cent of sales or 10.6 per cent of gross profit margins.32In the highly competitive fashion industry, this could be the defining driver of profitability.

Frequently Changing Tastes

Fashion cycles could also be notoriously short, especially in the urban womenswear segment. Trends came and went, which drove fashion retailers to introduce new fashions more often and avoid replenishing old items where “old” stock could necessitate a potential discount. At H&M, speed to sell-out rates ranged from 12 to 38 days in the first three quarters of 2018.33 On the surface, this looked like a strong metric; however, H&M tended to replenish sell-out items versus replacing them with new items. In the world of ever- changing consumer tastes, replenishment rates should ideally be low, reflecting a strong tie to consumers’ needs. This impacted both retailers’ inventory turnover ratios and ability to sell items at or near full price. Introducing new fashions frequently could have the positive desired effect of enticing customers back to the store more often. An average customer would visit the typical fashion store four times per year, while some fashion retailers, such as Zara, enticed their customers back as many as 17 times per year with fresh fashion choices appearing more often.34A fashion retailer’s ability to react quickly to shifting fashion preferences could be a defining success factor.

INDITEX AND ZARA—A UNIQUE APPROACH

Inditex was the public holding company for Zara and seven other retail brands, including Bershka, Massimo Dutti, Pull&Bear, and Stradivarius. After 23 years of diversifying into these new categories, Inditex still depended on Zara for the vast majority of its sales and profitability.35In 2017, Zara represented €16.62 billion of Inditex’s revenue across 2,251 stores in 96 markets (see Exhibit 4) and a full 70.1 per cent of its earnings before interest and taxes (EBIT).36

Inditex had been moving rapidly for the last decade. It had taken its sales from €5.67 billion in 2004 to

€23.34 billion in fiscal 2017.37 This had been accomplished through a focused geographic expansion effort that had seen the company grow to support 7,475 stores by the end of 2017, along with growing online sales in 47 markets.38Its recent focus for geographic growth was primarily Asia, where it had opened 593 stores in China alone by the end of 2014.39

The company’s approach was very different from that of its traditional competitors. For instance, it was highly vertically integrated, and unlike all of its competitors, it manufactured the majority of its own clothing. In fact, it manufactured over 60 per cent of its own products in what most would consider high- cost labour markets—Spain, Portugal, or other nearby countries—relying less on third-world and outsourced manufacturing.40Its competitors, by contrast, outsourced the vast majority of their production.

Unique Capabilities

Inditex had built a number of defining competencies, which its competitors did not possess. The first was associated with time to market. The company could move from a sketch of an idea to a product ready for shipment in as little as 10 to 15 days.41 This was precisely why Zara had been dubbed the champion of the relatively new “fast fashion” industry. However, Pablo Isla, chief executive officer (CEO) and chairman of Inditex, did not endorse this term. “I don’t identify with the concept of fast fashion,” he said. “We are not about selling a million striped T-shirts as fast as possible.” He went on to say that the success was “based not on speed but on accuracy, on understanding exactly what customers want, week by week, and store by store.”42

This highlighted a key capability at Inditex—its ability to identify customer needs and desires and translate these critical inputs back to the design teams in La Coruña. Zara achieved this through employee groups dubbed “commercials.” There were three essential levels of commercials that worked closely with one another at Zara. The design team commercials, which typically consisted of four employees—two product managers and two designers—were responsible for designs in a specific category, such as women’s sport clothing. They were given all the decision authority required to succeed, including independence in setting designs, ordering fabric, determining manufacturing quantities, and pricing. These teams decided what Zara would make and sell. In fact, they introduced roughly 12,000 new individual designs for Zara stores each year.43 These teams were supported by regional commercials responsible for liaising with store managers (and customers) across certain geographic footprints. Their overriding responsibility was to identify the clothing styles that would sell in their markets. They did this through observing what people were wearing (and, importantly, wanted to wear) along with the insights (and orders) coming from the store managers.44

Store managers were the third level of commercials. Their primary responsibility was to select the inventory they believed would sell in their stores—something they accomplished through talking with and observing customers. They had to also be up to the minute and intimate with their store inventory levels and sales. They ordered new inventory within each category in the store twice a week. For many years, Zara had chosen to not implement a store-wide inventory management system, requiring store managers to count inventory by hand. This, among other things, forced the store managers to be on the floor and, by default, to interact with customers. The insights gained from this interaction helped managers purchase inventory for their store that was more relevant and compelling for their customers. However, store managers would not always receive the items they ordered. At times, the regional commercials would place new items in stores to “see how they would sell.” They usually made these new clothes in small batches to avoid any significant markdowns in the event they were not popular.45This approach drove Zara’s industry leading fashion failure rates.

Commercials were encouraged to remain vigilant in introducing new items weekly and not restocking old items, giving Zara a replenishment rate of only 2.8 per cent.46 This led to two unique customer behaviours. Firstly, Zara customers would visit stores often (17 times per year versus 4.1 for brand loyal shoppers),47 as there were always new fashions to be had. Secondly, when customers found something they liked, they were motivated to avoid deferring their decision to purchase, as Zara had created a sense of scarcity; it simply would not be there next time. These two behaviours drove Zara to an industry-leading third quarter 2018 trailing 12-month inventory turnover ratio of 28:48.48

These three levels of commercial teams were the heart of Zara’s success, and they ultimately represented Zara’s delivery of what customers wanted, when they wanted it, as CEO Isla had implied.

A core capability at Zara related to its ability to efficiently manufacture clothes in small batches. Not only could it move a new item from concept to market very quickly, but it was able to accomplish this in small

batches, permitting it to test the market with very little risk.49 The challenges of having achieved this level of mass customization should not to be underestimated. Inditex invested heavily in automation within its manufacturing plants and tied this to effective management of its entire supply chain, with a focus on breaking down any bottlenecks in the manufacturing process. For instance, it operated a local dye and finishing plant close to its factories in La Coruña and did most of its own pre-cutting prior to delivering product to its sewing subcontractors. This was not without cost implications; its clothes typically cost 20 per cent more to manufacture than its competitors’ clothes, which were manufactured in vast quantities in third-world countries.50

Distribution was centrally managed through a large distribution centre in La Coruña. All clothes sold by Zara, even those manufactured in Portugal or Morocco (or China, for that matter), were sent to Spain for distribution. Bloomberg reported:

Beyond the distribution center are the 11 Zara-owned factories. Every shirt, sweater and dress made in them is sent directly to the distribution centre via an automated underground monorail. There are 124 miles of track. Across the surrounding Galicia region are subcontractors, some of whom have worked for the company since Amancio Ortega founded it in 1975.51

This enabled Zara to ship new inventory to every store in its network at least twice a week. Orders typically arrived two days after a store placed its request.

Additionally, Zara looked to manage its production costs by focusing on fabricating apparel that was designed to be worn only a few times, driving a lower cost of materials. This did not seem to be an issue with its customers, who enjoyed changing their fashions often.

Marketing

The foundation of Zara’s marketing strategy had always been its stores. New stores were opened at a dizzying pace: 0.62 net openings per day over the five years to 2017.52 The company took store location, design, and layout very seriously. In fact, Zara had “a full-time team of architects and visual-merchandising experts whose sole job at Zara HQ [headquarters] is to design and curate every aspect of the store, from the sleek decor and light-bulb colour to the music being played and the exact positioning of clothing.”53 Window-front designs were viewed as its pre-eminent form of advertising. In fact, Zara had a “full team of window-front designers who constantly travel around to international locations to understand the culture and customers of each store. They then create the window design that is unique to the store, and all the props and details are then shipped to each store to be put up under strict guidelines.”54 Zara traditionally had spent lavishly on its store locations. In fact, it completely revamped each store every four to five years, with minor tweaks in between. Its stores were characterized by a high-end look and feel, along with relatively low levels of inventory. This was somewhat anti-intuitive in relation to its competitors, who liked to fill their stores with inventory in an attempt to optimize the revenue of their retail space investment. On the contrary, Zara had always been focused on making the shopping experience as pleasant as possible for its customers, enticing them to come back more often.

There were 2,238 Zara stores across 96 markets at the end of 2017, driving €16.6 billion in sales.55These stores were primarily situated in the high-end retail sectors of major urban centres. Inditex had recently announced the opening of a 4,366 square metre store in the heart of New York’s SoHo district for an astonishing $280 million. Ironically, this property was the former home of Old Navy.56 In March 2016, it had opened a 2,800 square metre store in the World Trade Centre in the heart of New York’s financial district.

Zara spent very little on advertising, only advertising (some) new store openings and twice-yearly sales events. It spent just 0.3 per cent of its revenue on advertising,57 versus the industry standard of 3.5 per cent. There was no advertising line item in its financial reports, as this category had not amounted to a material expenditure. Marketing magazine’s assistant editor, Belle Kwan, discussed Zara’s approach to advertising:

No four-page spread in a glossy publication, no gaudy red posters with tacky WordArt bubbles screaming discounts, no half-naked B-grade celebrity with perfect hair prancing across a billboard.

This is a story about the brand that made it sans advertising, sans endorsement and sans almost all forms of mainstream marketing. And when we say “made it,” we mean a loyal global following across 78 countries, and a name that draws squeals of excitement from consumers and nods of respect from industry experts.58

Zara typically priced its clothes an average of 15 per cent lower than its competitors.59It had been Ortega’s goal from his humble beginnings in La Coruña in 1975 to provide good quality fashion clothing at affordable prices.60The difference was Zara did not look like any discount fashion store in the marketplace. As Derek Thompson of The Atlantic put it, Zara liked to “cozy up to the most famous brands in the world to sing their luxury ambitions even as they profit off a brilliant, cheap, short supply chain that delivers similar fashion at a much lower price.”61 Zara enjoyed placing its stores close to luxury brands, such as Prada and Gucci, which, of course, tried to keep as far from Zara as possible.

COMPETING INDUSTRY BUSINESS MODEL

Historically, industry titans such as Gap introduced the majority of their new clothing launches twice a year, during the spring and fall fashion seasons. These introductions were preceded by up to nine months of centralized planning, production, and marketing. New line items were revealed to the market on fashion runways and vetted through a team of elite fashion designers and corporate executives. Small runs were made at third-world manufacturers, shipped to centralized facilities, vetted once more, changed, and finalized. At this point, large orders were placed with these manufacturers for production at ultra-low per- unit cost. Orders were shipped and stored in regional warehouse facilities relatively close to retail outlets. Retail point-of-sale strategies were drawn up and store layouts designed. Inventory levels, determined centrally, were shipped to stores. Subsequently, the advertising and selling began in full force to push product offerings to prospective customers.62

This approach carried the risk of fashion misses, which, traditionally, were more than offset by the ultra- low costs of manufacturing offshore. This led to industry-standard gross profit margins of approximately

38.3 per cent in 2017.63 Growth was accomplished through both geographic expansion and brand expansion. For example, Gap grew from 1,640 stores in 200464 to a peak of 3,721 in 2015 and was currently sitting at 3,594 stores.65Gap also grew across multiple brands representing different market niches, including Gap, Banana Republic, Old Navy, Athletica, and Intermix.66It was not uncommon to have multiple Gap-branded stores in one mall or shopping district.

INNOVATIVE NEW FASHION COMPETITORS

As with any successful business model that changed an industry, Zara’s model inevitably led to the emergence of a host of new competitors, who presented either variations of the model or totally new approaches. Zara was experiencing this first hand with the emergence of competitors such as Uniqlo Co. Ltd. (Uniqlo) and Boohoo.com (Boohoo).

Uniqlo was a Japanese firm that had been labelled a technology company, not a fashion company, and it had a sole focus on revolutionary fashion changes through technology innovation around the products, not the fashion. Kensuke Suwa, Uniqlo’s director of global marketing, explained its approach:

Between fashion and sports is a new area. . . There are a lot of fashion trends going on, but there is no true innovation that impacts your actual life. How to make your life better could be in the middle between fashion and sports. For example, athletes wear technically sophisticated uniforms; some of the essence of that could result in better clothes that would change clothing itself, instead of just following fashion trends.67

This approach helped Uniqlo quickly grow to 3,445 stores as of the end of fiscal 2018, with a sales forecast of $18.2 billion in its 2017 fiscal year.68 In 2018, Uniqlo was the largest apparel chain in Asia, accounting for 6.5 per cent of apparel sales in Japan alone, with an eye to becoming number one in the world and a near-term goal of expanding beyond its 50 stores in the United States.69

Boohoo, a U.K. online “ultra-fast fashion” retailer, had seen tremendous growth since its inception in 2006, with 2018 sales of £579.8 million70 and gross margins rivalling those of Zara at 52.8 per cent.71 With a direct focus on 16–30 year olds, Boohoo took products from concept to sale in just two weeks, putting over 100 new products on its website daily.72Boohoo’s sales had been growing outside the United Kingdom in both Europe and the United States across a growing number of online brands: Boohoo, PrettyLittleThing, and NastyGal.73

NEXT STEPS

The competitive landscape was changing. The fast fashion world Zara had invented and dominated was changing. Perhaps it was time to reposition how Zara and the other Inditex brands competed in this changing world. Zara had changed the retail fashion industry once. Could it do it again?

EXHIBIT 1: INDITEX 2012/2017 SELECT FINANCIAL DATA (€ BILLIONS)

| 2017 | 2016 | 2015 | 2014 | 2013 | 2012 | CAGR | |

| Revenues | |||||||

| Net Sales | 25.3 | 23.3 | 20.9 | 18.1 | 16.7 | 15.9 | 11% |

| Profits and Cash Flow | |||||||

| EBITDA | 5.3 | 5.1 | 4.7 | 4.1 | 3.9 | 3.9 | 9% |

| EBIT | 4.3 | 4.0 | 3.7 | 3.2 | 3.1 | 3.1 | 10% |

| Net Income | 3.4 | 3.2 | 2.9 | 2.5 | 2.4 | 2.4 | 10% |

| Net Income After Minorities | 3.4 | 3.2 | 2.9 | 2.5 | 2.4 | 2.4 | 10% |

| Cash Flow | 4.4 | 4.4 | 3.9 | 3.4 | 3.2 | 3.2 | |

| Financial Structure | |||||||

| Group Equity | 13.5 | 12.7 | 11.4 | 10.4 | 9.2 | 8.4 | 11% |

| Net Financial Debt (Cash) | −6.4 | −6.1 | −5.3 | −4.0 | −4.1 | −4.1 | 12% |

| Other Information | |||||||

| Number of Stores | 7,475 | 7,292 | 7,013 | 6,683 | 6,340 | 6,009 | |

| In Spain | 1,688 | 1,787 | 1,826 | 1,822 | 1,858 | 1,930 | |

| Abroad | 5,787 | 5,505 | 5,187 | 4,861 | 4,482 | 4,079 |

Notes: € = EUR = euro; €1 = US$1.147 as of January 9, 2019. CAGR = compound annual growth rate; EBITDA =earnings before interest, tax, depreciation, and amortization; EBIT = earnings before interest and taxes.

Source: Inditex, “Financial Data,” accessed January 15, 2019, https://www.inditex.com/en/investors/investor- relations/financial-data.

EXHIBIT 2: THE GROWING EMERGING ECONOMY AND MIDDLE CLASS HOUSEHOLD SPEND

Copyright: @ McKinsey & Company.

Source: Richard Dobbs, Jaana Remes, James Manyika, Charles Roxburgh, Sven Smit, and Fabian Schaer, Urban World: Cities and the Rise of the Consuming Class, 27, McKinsey & Company, June 2012, accessed February 18, 2015, https://www.mckinsey.com/featured-insights/urbanization/urban-world-cities-and-the-rise-of-the-consuming-class.

EXHIBIT 3: GLOBAL WOMEN’S APPAREL MARKET GROWTH

Note: CAGR = compound annual growth rate. Copyright: @ McKinsey & Company.

Source: Nathalie Remy, Jennifer Schmidt, Charlotte Werner, and Maggie Lu, Unleashing Fashion Growth City by City, McKinsey & Company, September 2014, 2, accessed January 22, 2015, https://www.mckinsey.com/~/media/mckinsey/dotco m/client_service/marketing%20and%20sales/pdfs/unleashing_fashion_growth.ashx.

EXHIBIT 4: INDITEX BRANDS AT A GLANCE

| Net Sales | Number of | Net Openings | Markets | Online | |

| (€ millions) | Stores | in 2017 | Served | Markets | |

| Zara | 16,620 | 2,251 | 51 | 96 | 46 |

| Pull & Bear | 1,747 | 979 | 6 | 77 | 33 |

| Massimo Dutti | 1,765 | 780 | 15 | 77 | 37 |

| Bershka | 2,227 | 1,098 | 17 | 79 | 35 |

| Stradivarius | 1,480 | 1,017 | 23 | 76 | 32 |

| Oysho | 570 | 670 | 34 | 65 | 33 |

| Zara Home | 830 | 590 | 38 | 75 | 37 |

| Uterque | 97 | 90 | 12 | 41 | 30 |

| Total | 25,336 | 7,475 | 196 | ||

Note: € = EUR = euro; €1 = US$1.147 as of January 9, 2019.

Source: Created by case authors based on data from Inditex, Inditex Annual Report 2017, 16–23, June 2017, accessed January 15, 2017, https://www.inditex.com/documents/10279/563475/2017+Inditex+Annual+Report.pdf/f5bebfa4-edd2-ed6d- 248a-8afb85c731d0.

ENDNOTES

1 This case has been written on the basis of published sources only. Consequently, the interpretation and perspectives presented in this case are not necessarily those of Inditex or any of its employees.

2 Most would agree that the term fast fashion represented only a part of Zara’s core business model, not the entire foundation of its success.

3 Devangshu Dutta, “Retail @ The Speed of Fashion,” Third Eyesight, 3, 2002, accessed August 31, 2015, http://thirdeyesight.in/articles/ImagesFashion_Zara_Part_I.pdf.

4 Graham Ruddick, “How Zara Became the World’s Biggest Fashion Retailer,” Telegraph, October 20, 2014, accessed August 31, 2015, www.telegraph.co.uk/finance/newsbysector/retailandconsumer/11172562/How-Inditex-became-the-worlds-biggest- fashion-retailer.html.

5 Vivienne Walt, “Meet Amancio Ortega: The Third-Richest Man in the World,” Fortune, January 8, 2013, accessed January 20, 2015, http://fortune.com/2013/01/08/meet-amancio-ortega-the-third-richest-man-in-the-world/.

6 “The World’s Billionaires,” Forbes, accessed January 20, 2015, www.forbes.com/profile/amancio-ortega/.

7 Inditex, “Our History,” accessed January 20, 2015, www.inditex.com/our_group/our_history.

8 Andrew McAfee, Vincent Dessain, and Anders Sjoman, Zara: IT for Fast Fashion, Case Study (Boston, MA: Harvard Business Publishing, 2004), 3. Available from Ivey Publishing, product no. 604081.

9 € = EUR = euro; €1 = US$1.147 as of January 9, 2019; all currency amounts are in € unless specified otherwise.

10 Inditex, Inditex Annual Report 2017, accessed January 9, 2019, www.inditex.com/documents/10279/563475/2017+Inditex

+Annual+Report.pdf/f5bebfa4-edd2-ed6d-248a-8afb85c731d0.

11 Inditex, “Financial Data,” accessed January 9, 2019, www.inditex.com/en/investors/investor-relations/financial-data.

12 Imran Amed, Anita Balchandani, Marco Beltrami, Achim Berg, Saskia Hedrich, and Felix Rölkens, The State of Fashion 2019: A Year of Awakening, 64, McKinsey & Company, November 2018, accessed January 9, 2019, www.mckinsey.com/~/media/McKinsey/Industries/Retail/Our%20Insights/The%20State%20of%20Fashion%202019%20A% 20year%20of%20awakening/The-State-of-Fashion-2019-vF.ashx; All dollar amounts in the case are U.S. dollars.

13 Ibid.

14 “The Future of Fashion is Urban,” TranslateMedia, January 24, 2018, accessed January 9, 2019, www.translatemedia.com/translation-blog/future-fashion-urban/.

15 Krones AG, Annual Report for Krones AG 2013, 57, accessed January 21, 2015, www.krones.com/media/downloads/GB_2013_AG_e.pdf.

16 Carsten Keller, Karl-Hendrik Magnus, Saskia Hedrich, Patrick Nava, and Thomas Tochtermann, “Succeeding in Tomorrow’s Global Fashion Market,” McKinsey & Company, September 2014, accessed January 22, 2015, http://mckinseyonmarketingandsales.com/ succeeding-in-tomorrows-global-fashion-market; “The Future of Fashion is Urban,” op. cit.

17 Neil Newman, “The Rise and Rise of Asia’s Middle Class,” GLINT, August 16, 2018, accessed January 9, 2019, https://glintpay.com/economics/rise-rise-asias-middle-class/; Deere & Company, John Deere Committed to Those Linked to the Land — Strategy Overview, 19, December 2014, accessed January 20, 2019, https://glintpay.com/economics/rise-rise- asias-middle-class/.

18 Amed, Balchandani, Beltrami, Berg, Hedrich, and Rölkens, op. cit. 7; Lily Kuo, “The World’s Middle Class Will Number 5 Billion by 2030,” Quartz, January 14, 2013, accessed January 20, 2015, http://qz.com/43411/the-worlds-middle-class-will- number-5-billion-by-2030/.

19 Nathalie Remy, Jennifer Schmidt, Charlotte Werner, and Maggie Lu, Unleashing Fashion Growth City by City, McKinsey & Company, 2, October 2013, accessed January 20, 2015, www.mckinsey.com/~/media/mckinsey/dotcom/client_service/mark eting%20and%20sales/pdfs/unleashing_fashion_growth.ashx.

20 Nathalie Remy, Jennifer Schmidt, Charlotte Werner, and Maggie Lu, “Fashion Sense: Apparel Companies Should Look to Cities for Growth,” Forbes, April 23, 2013, accessed January 20, 2015, www.forbes.com/sites/mckinsey/2013/04/23/fashion- sense-apparel-companies-should-look-to-cities-for-growth/.

21 J.C., “A ‘Distinctly South Asian’ Tragedy,” Economist, December 6, 2012, accessed August 31, 2015, www.economist.com/blogs/banyan/2012/12/garment-factory-fires.

22 “Sizing Up the Plus Sized Market: Segment Up 5 Per cent, Reaching $17.5 Billion,” The NPD Group, June 30, 2014, accessed January 20, 215, www.npd.com/wps/portal/npd/us/news/press-releases/sizing-up-the-plus-sized-market-segment- up-5-percent-reaching-17-billion/; Katie Little, “Outsize Growth, Underserved Market: Rent the Runway’s Plus-Size Bet,” CNBC, September 29, 2013, accessed January 20, 2015, www.cnbc.com/id/101065567#.

23 Deborah Weinswig, “Will J. Crew Announcement Disrupt The $46 Billion Women’s Plus-Size Market?,” Forbes, July 20, 2018, accessed January 14, 2019, www.forbes.com/sites/deborahweinswig/2018/07/20/a-land-grab-is-likely-under-way-for-the-46- billion-womens-plus-size-market-opportunity/#325d4de03489; “The Plus-Size Clothing Market in 2018 and Beyond,” LUXLife Magazine, accessed January 14, 2019, www.lux-review.com/the-plus-size-clothing-market-in-2018-and-beyond/.

24Imran Amed, Achim Berg, Sara Kappelmark, Saskia Hedrich, Johanna Andersson, and Martine Drageset, The State of Fashion 2018, 16, McKinsey & Company, 2017, accessed January 9, 2019, https://cdn.businessoffashion.com/reports/The_State_of_Fa shion_2018_v2.pdf; James Melton, “E-commerce Accounts for 27% of US Apparel Sales,” Digital Commerce 360, July 11, 2018, accessed January 9, 2019, www.digitalcommerce360.com/article/online-apparel-sales-us/; “Apparel: United States,” Statista, accessed January 14, 2019, www.statista.com/outlook/90000000/109/apparel/united-states.

25 Achim Berg, Miriam Heyn, Felix Rolkens, and Patrick Simon, “Faster Fashion: How to Shorten the Apparel Calendar,” McKinsey & Company, May 2018, accessed January 14, 2019, www.mckinsey.com/industries/retail/our-insights/faster- fashion-how-to-shorten-the-apparel-calendar.

26 Textile Exchange, Preferred Fiber & Materials – Market Report 2018, 9, accessed January 14, 2019, https://textileexchange.org/downloads/2018-preferred-fiber-and-materials-market-report/.

27 Cotton Incorporated, “Monthly Economic Letter,” December 2018, accessed January 14, 2019, www.cottoninc.com/market- data/monthly-economic-newsletter/.

28 Katerine Fox, “Facing an Ageing Population in Fashion,” Not Just a Label, February 22, 2018, accessed January 14, 2019, www.notjustalabel.com/editorial/facing-ageing-population-fashion.

29 Zara defined its target customers as “young, price conscious and highly sensitive to the latest fashion trends.” Arif Harbott, “Analysing Zara’s Business Model,” Medium (blog), March 3, 2011, accessed August 31, 2015, www.harbott.com/2011/03/03/analysing-zaras-business-model/.

30 Pam Danziger, “Battle of the Fast Fashion Giants: Why Zara Wins, H&M Loses,” Unity Marketing, May 12, 2018, accessed January 14, 2019, https://unitymarketingonline.com/battle-of-the-fast-fashion-giants-why-zara-wins-hm-loses/.

31 Doug Hardman, Simon Harper, and Ashok Notaney, Keeping Inventory — and Profits — Off the Discount Rack, PWC, 2, 2008, accessed January 20, 2015, https://nanopdf.com/download/keeping-inventory-and-profitsoff-the-discount-rack_pdf.

32 “Advertising expenditure of The Gap, In. worldwide from 2012 to 2018 (in million U.S. dollars),” statista, accessed April 5, 2019, www.statista.com/statistics/422492/ad-spend-of-the-gap-inc-worldwide/.

33 Kexin, “Speed to Sellout: What is it & how do Zara’s and H&M’s compare?,” omnilytics, November 30, 2018, accessed January 14, 2019, https://omnilytics.co/blog/what-is-speed-to-sellout-rate-retail.

34 Adrian Swinscoe, “Customer Focus in Action: Why ZARA Stores Became a Customer Magnet,” Adrian Swinscoe (blog), December 21, 2011, accessed August 31, 2015, www.adrianswinscoe.com/customer-focus-in-action-why-zara-stores- became-a-customer-magnet/.

35 In 2017, Zara represented €3.024 billion of Inditex’s €4.314 billion in earnings before interest and taxes; Inditex, Inditex Annual Report 2017, op. cit., 325.

36 Ibid, 17, 326.

37 Inditex, Inditex Annual Report 2004, 13, June 2005, accessed January 20, 2015, www.inditex.com/documents/10279/245571/AnnualReport_2004.pdf/2bf4a31f-aa2e-4efc-86c4-1fb201211be6; Inditex, Inditex Annual Report 2017, op. cit., 325.

38 Ibid, 8, 325.

39 “Inditex Group’s Number of Stores in Asia and Africa in 2018, by Country,” Statista, March 2018, accessed January 14, 2019, www.statista.com/statistics/268829/number-of-stores-of-the-inditex-group-in-asia-and-africa-by-country/.

40 Nick, “How Zara Sells out 450+ Million Items a Year without Wasting Money on Marketing,” Beeketing, March 1, 2018, accessed January 14, 2019, https://beeketing.com/blog/zara-growth-story/.

41 Greg Petro, “The Future of Fashion Retailing: The Zara Approach (Part 2 of 3),” Forbes, accessed April 5, 2019, www.forbes.com/sites/gregpetro/2012/10/25/the-future-of-fashion-retailing-the-zara-approach-part-2-of-3/#6b345b77aa4b.

42 Tobias Buck, “Fashion: A Better Business Model,” Financial Times, June 18, 2014, accessed January 22, 2015, www.ft.com/intl/cms/s/2/a7008958-f2f3-11e3-a3f8-00144feabdc0.html#slide0.

43 “The Secret of Zara’s Success: A Culture of Customer Co-creation,” Martin Roll, March 2018, accessed January 14, 2019, https://martinroll.com/resources/articles/strategy/the-secret-of-zaras-success-a-culture-of-customer-co-creation/.

44 Ruddick, op. cit.

45 Kerry Capell, “Zara Thrives by Breaking All the Rules,” Bloomberg, October 8, 2008, accessed August 31, 2015, www.bloomberg.com/bw/stories/2008-10-08/zara-thrives-by-breaking-all-the-rules.

46 Katie Smith, “Zara vs H&M — Who’s in the Global Lead?,” Edited (blog), April 15, 2014, accessed August 31, 2015, https://editd.com/blog/2014/04/zara-vs-hm-whos-in-the-global-lead/.

47 Deborah Weinswig, “Retailers Should Think Like Zara: What We Learned At The August Magic Trade Show,” Forbes, August 28, 2017, accessed January 14, 2019, www.forbes.com/sites/deborahweinswig/2017/08/28/retailers-should-think-like- zara-what-we-learned-at-the-august-magic-trade-show/#630ab2f13e52.

48 “Zara Investment Holding (ZARA),” Investing.com, accessed January 14, 2019, https://ca.investing.com/equities/zara- investmen-ratios.

49 Gemma Goldfingle, “Inside Inditex: How Zara Became a Global Fashion Phenomenon,” Retail Week, October 20, 2014, accessed August 31, 2015, www.retail-week.com/sectors/fashion/inside-inditex-how-zara-became-a-global-fashion- phenomenon/5065325.article.

50 Hardman, Harper, and Notaney, op. cit., 2.

51 Susan Berfield and Manuel Baigorri, “Zara’s Fast-Fashion Edge,” Bloomberg, November 14, 2013, accessed January 22, 2015, www.businessweek.com/articles/2013-11-14/2014-outlook-zaras-fashion-supply-chain-edge.

52 Calculated as follows: 7,475 stores to the end of 2017, compared with 6,340 in 2013 across 1,825 days; Inditex, Inditex Annual Report 2017, op. cit.

53 Mary Hanbury, “Zara Has a Fleet of Secret Stores Where it Masters its Shop Design and Plots How to Get You to Spend Money,” Business Insider, September 24, 2018, accessed January 14, 2019, www.businessinsider.com/zara-has-secret-test- stores-photos-2018-9.

54 Belle Kwan, “Spanish Domination — Zara Brand Profile,” Marketing, September 23, 2011, accessed February 4, 2015, www.marketingmag.com.au/blogs/spanish-domination-6575/#.VNJL7lXF_uI.

55 “Company Profile – Global Growth Opportunities,” Inditex, accessed January 9, 2019, www.inditex.com/en/investors/investor-relations/results-and-presentations.

56 Laura Gurfein, “Zara’s New Soho Store Is Open and So Ready for Spring,” Racked, March 3, 2016, accessed January 9, 2019, https://ny.racked.com/2016/3/3/11153970/zara-nyc-soho-now-open.

57 Matt Duczeminski, “Spotlight on Zara: Lessons from a Brand that Spends Next to Nothing on Ads,” PostFunnel, November 5, 2018, accessed January 14, 2019, https://postfunnel.com/spotlight-zara-lessons-brand-spends-next-nothing-ads/.

58 Kwan, op. cit.

59 Hardman, Harper, and Notaney, op. cit., 2.

60 Channing Hargrove, “10 Crazy Things You Didn’t Know About Zara,” REFINERY29, July 25, 2017, accessed April 5, 2019, www.refinery29.com/en-us/2017/07/165057/zara-secrets-richest-man-documentary-preview.

61 Derek Thompson, “Zara’s Big Idea: What the World’s Top Fashion Retailer Tells Us about Innovation,” Atlantic, November 13, 2012, accessed January 23, 2015, www.theatlantic.com/business/archive/2012/11/zaras-big-idea-what-the-worlds-top- fashion-retailer-tells-us-about-innovation/265126/.

62 Hiroko Tabuchi and Hilary Stout, “Gap’s Fashion-Backward Moment,” New York Times, June 20, 2015, accessed August 31, 2015, www.nytimes.com/2015/06/21/business/gaps-fashion-backward-moment.html?_r=0.

63 GAP Inc., 2017 Annual Report, 17, March 20, 2018, accessed January 15, 2019, http://investors.gapinc.com/phoenix.zhtml?c=111302&p=irol-reportsAnnual.

64 Gap Inc., 2004 Annual Report, 9, accessed January 29, 2015, http://media.corporate- ir.net/media_files/IROL/11/111302/GPS_AR_04.pdf.

65 GAP Inc., 2017 Annual Report, op. cit., 17.

66 Intermix was a brand with 30 boutiques across Canada and the United States that was acquired by Gap in December 2012. 67 Vikram Alexei Kansara, “With an Evolutionary Approach, Uniqlo Aims to Create New Category,” The Business of Fashion, April 19, 2013, accessed February 2, 2015, www.businessoffashion.com/2013/04/with-an-evolutionary-approach-uniqlo-aims- to-create-new-category.html. Disclosure: Vikram Kansara travelled to Paris as a guest of Uniqlo.

68 “About Fast Retailing,” Fast Retailing, accessed January 15, 2019, www.fastretailing.com/eng/about/business/aboutfr.html

; “#181 Fast Retailing,” Forbes, accessed January 15, 2019, www.forbes.com/companies/fast-retailing/#2eb0e96446f7.

69 “About Fast Retailing,” op. cit.; Nikita Biryukov, “Uniqlo Head Would Close U.S. Stores over Trump’s Suggested Policy,” NBC News, March 31, 2017, accessed January 15, 2019, www.nbcnews.com/news/us-news/uniqlo-head-would-close-u-s- stores-over-trump-s-n741371.

70 £ = GBP = British pound; €1 = £0.8995 on January 9, 2019.

71 Boohoo.com PLC, Boohoo.com PLC Annual Report and Accounts 2018, accessed January 15, 2019, www.boohooplc.com/~/media/Files/B/Boohoo/reports-and-presentations/4042-boohoo-randa-hyperlink.pdf.

72 Daphne Howland, “Report: ‘Ultra-Fast’ Fashion Players Gain on Zara, H&M,” Retail Dive, May 22, 2017, accessed January 15, 2019, www.retaildive.com/news/report-ultra-fast-fashion-players-gain-on-zara-hm/443250/.

73 Boohoo.com PLC, op. cit., 13.

Zara's business model could be disruptive to the apparel industry due to its ability to provide “fast fashion”. While its competitors hold goods in inventory for a long period of time, Zara does not have any finished goods inventory as its supply chain allowed products to be produced and delivered to stores quickly.