I have attached all the files provided by the instructor. Just need to follow the instruction and need to include all the items mentioned. Should be plagiarism-free.

Entering the ConversationThink about an activity that you do particularly well: cooking, playing the piano, shooting a basketball, even something as basic as driving a car. If you reflect on this activity, you’ll realize that once you mastered it you no longer had to give much conscious thought to the various moves that go into doing it. Performing this activity, in other words, depends on your having learned a series of complicated moves—moves that may seem mysterious or difficult to those who haven’t yet learned them.

The same applies to writing. Often without consciously realizing it, accomplished writers routinely rely on a stock of established moves that are crucial for communicating sophisticated ideas. Hence this class, which will guide you through some of the basic moves of academic writing.

It is true, of course, that critical thinking and writing go deeper than any set of linguistic formulas, requiring that you question assumptions, develop strong claims, offer supporting reasons and evidence, consider opposing arguments, and so on. But these deeper habits of thought cannot be put into practice unless you have a strategy for expressing them in clear, organized ways. Thus, the “they say; I say” approach.

State Your Own Ideas as a Response to OthersThe most important rhetorical concept that we will focus on in this class is the “they say; I say” approach to writing. If there is any one point that I hope you will take away from ENGL 1302, it is the importance not only of expressing your ideas (“I say”) but of presenting those ideas as a response to some other person or group (“they say”). Remember this: the underlying structure of effective academic writing—and of responsible public discourse—resides not just in stating your own ideas but in listening closely to others around you, summarizing their views in a way that they will recognize, and responding with your own ideas in kind. Broadly speaking, academic writing is argumentative writing, and I believe that to argue well you need to do more than assert your own position. You need to enter a conversation, using what others say (or might say) as a launching pad or sounding board for your own views. For this reason, one of the main pieces of advice in this class is to write the voices of others into your text.

The best academic writing has one underlying feature: it is deeply engaged in some way with other people’s views. Too often, however, academic writing is taught as a process of saying “true” or “smart” things in a vacuum, as if it were possible to argue effectively without being in conversation with someone else. If you have been taught to write a traditional five-paragraph essay, for example, you have learned how to develop a thesis and support it with evidence. This is good advice as far as it goes, but it leaves out the important fact that in the real world we don’t make arguments without being provoked. Instead, we make arguments because someone has said or done something (or perhaps not said or done something) and we need to respond: “I can’t see why you like the Lakers so much”; “I agree: it was a great film”; “That argument is contradictory.” If it weren’t for other people and our need to challenge, agree with, or otherwise respond to them, there would be no reason to argue at all.

“Why Are You Telling Me This?”

To make an impact as a writer, then, you need to do more than make statements that are logical, well supported, and consistent. You must also find a way of entering into conversation with the views of others, with something “they say.” The easiest and most common way writers do this is by summarizing what others say and then using it to set up what they want to say.

“But why,” as many students ask, “do I always need to summarize the views of others to set up my own view? Why can’t I just state my own view and be done with it?” Why indeed? After all, “they,” whoever they may be, will have already had their say, so why do you have to repeat it? Furthermore, if they had their say in print, can’t readers just go and read what was said themselves?

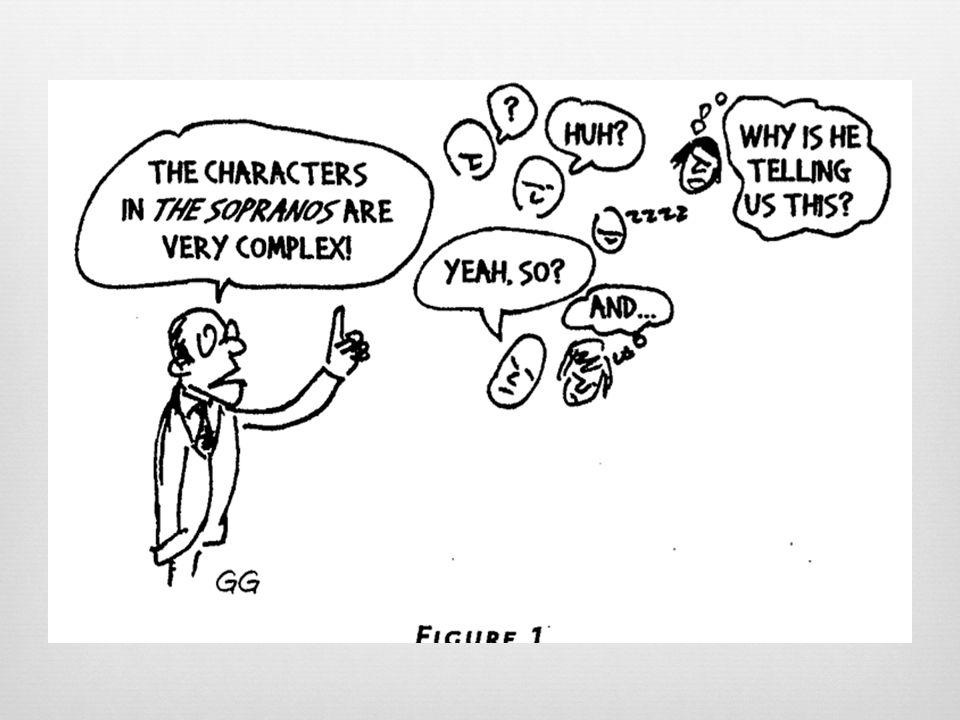

The answer is that if you don’t identify the “they say” you’re responding to, your own argument probably won’t have a point. Readers will wonder what prompted you to say what you’re saying and therefore motivated you to write. As the figure below suggests, without a “they say,” what you are saying may be clear to your audience, but why you are saying it won’t be.

Even if we aren’t familiar with the show The Sopranos, it’s easy to grasp what the speaker means here when he says that its characters are very complex. But it’s hard to see why the speaker feels the need to say what he is saying. “Why,” as one member of his imagined audience wonders, “is he telling us this?” So the characters are complex—so what?

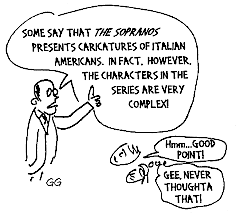

Now look at what happens to the same proposition when it is presented as a response to something “they say”:

I hope you agree that the same claim—“the characters in The Sopranos are very complex”—becomes much stronger when presented as a response to a contrary view: that the show’s characters are “caricatures of Italian Americans.” Unlike the speaker in the first cartoon, the speaker in the second has a clear goal or mission: to correct what he sees as a mistaken characterization.

The As-Opposed-To-What Factor

To put my point another way, framing your “I say” as a response to something “they say” gives your writing an element of contrast without which it won’t make sense. It may be helpful to think of this crucial element as an “as-opposed-to-what factor” and, as you write, to continually ask yourself, “Who says otherwise?” and “Does anyone dispute it?” Behind the audience’s “Yeah, so?” and “Why is he telling us this?” in the first cartoon above lie precisely these types of “As opposed to what?” questions. The speaker in the second cartoon, I think, is more satisfying because he answers these questions, helping us see his point that The Sopranos presents complex characters rather than simple Italian American stereotypes.

How It’s Done: Three Examples

Many accomplished writers make explicit “they say” moves to set up and motivate their own arguments. One famous example is Martin Luther King Jr.’s “Letter from Birmingham Jail,” which consists almost entirely of King’s eloquent responses to a public statement by eight clergymen deploring the civil rights protests he was leading. The letter—which was written in 1963, while King was in prison for leading a demonstration against racial injustice in Birmingham—is structured almost entirely around a framework of summary and response, in which King summarizes and then answers their criticisms. In one typical passage, King writes as follows.

You deplore the demonstrations taking place in Birmingham. But your statement, I am sorry to say, fails to express a similar concern for the conditions that brought about the demonstrations.

Martin Luther King Jr., “Letter from Birmingham Jail”

King goes on to agree with his critics that “It is unfortunate that demonstrations are taking place in Birmingham,” yet he hastens to add that “it is even more unfortunate that the city’s white power structure left the Negro community with no alternative.” King’s letter is so thoroughly conversational, in fact, that it could be rewritten in the form of a dialogue or play.

King’s critics say _______

King responses by saying _______

The critics say _______

King responds _______

Clearly, King would not have written his famous letter were it not for his critics, whose views he treats not as objections to his already-formed arguments but as the motivating source of those arguments, their central reason for being. He quotes not only what his critics have said (“Some have asked: ‘Why didn’t you give the new city administration time to act?’”), but also things they might have said (“One may well ask: ‘How can you advocate breaking some laws and obeying others?’”)—all to set the stage for what he himself wants to say.

A similar “they say / I say” exchange opens an essay about American patriotism by the social critic Katha Pollitt, who uses her own daughter’s comment to represent the patriotic national fervor after the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001.

My daughter, who goes to Stuyvesant High School only blocks from the former World Trade Center, thinks we should fly the American flag out our window. Definitely not, I say: the flag stands for jingoism and vengeance and war. She tells me I’m wrong—the flag means standing together and honoring the dead and saying no to terrorism. In a way we’re both right. . . .

Katha Pollitt, “Put Out No Flags”

As Pollitt’s example shows, the “they” you respond to in crafting an argument need not be a famous author or someone known to your audience. It can be a family member like Pollitt’s daughter, or a friend or classmate who has made a provocative claim. It can even be something an individual or a group might say—or a side of yourself, something you once believed but no longer do, or something you partly believe but also doubt. The important thing is that the “they” (or “you” or “she”) represent some wider group with which readers might identify—in Pollitt’s case, those who patriotically believe in flying the flag. Pollitt’s example also shows that responding to the views of others need not always involve unqualified opposition. By agreeing and disagreeing with her daughter, Pollitt enacts what is known as the “yes and no” response, reconciling apparently incompatible views.

While King and Pollitt both identify the views they are responding to, some authors do not explicitly state their views but instead allow the reader to infer them. See, for instance, if you can identify the implied or unnamed “they say” that the following claim is responding to.

I like to think I have a certain advantage as a teacher of literature because when I was growing up I disliked and feared books.

Gerald Graff, “Disliking Books at an Early Age”

In case you haven’t figured it out already, the phantom “they say” here is the common belief that in order to be a good teacher of literature, one must have grown up liking and enjoying books.

Don’t Shy Away from Controversy

As you can see from these examples, many writers use the “they say / I say” format to challenge standard ways of thinking and thus to stir up controversy. This point may come as a shock to you if you have always had the impression that in order to succeed academically you need to play it safe and avoid controversy in your writing, making statements that nobody can possibly disagree with. Though this view of writing may appear logical, it is actually a recipe for flat, lifeless writing and for writing that fails to answer the “so what?” and “who cares?” questions. “Youth homelessness in Dallas is a problem we need to solve” may be a perfectly true statement, but precisely because nobody is likely to disagree with it, it goes without saying and thus would seem pointless if said.

But just because controversy is important doesn’t mean you have to become an attack dog who automatically disagrees with everything others say.

Disagreeing Without Being DisagreeableThere certainly are occasions when strong critique is needed. It’s hard to live in a deeply polarized society like our current one and not feel the need at times to criticize what others think. But even the most justified critiques fall flat unless we really listen to and understand the views we are criticizing:

While I understand the impulse to _____, my own view is _____.

Even the most sympathetic audiences, after all, tend to feel manipulated by arguments that scapegoat and caricature the other side.

Furthermore, genuinely listening to views you disagree with can have the salutary effect of helping you see that beliefs you’d initially disdained may not be as thoroughly reprehensible as you’d imagined. Thus, the type of “they say / I say” argument that I promote in this class can take the form of agreeing up to a point or, as the Pollitt example above illustrates, of both agreeing and disagreeing simultaneously, as in:

While I agree with X that _____ , I cannot accept her overall conclusion that _____.

While X argues _____, and I argue _____, in a way we’re both right.

Agreement cannot be ruled out, however:

I agree with _____ that _____.

Though the immediate goal of this course is to help you become a better writer, at a deeper level it invites you to become a certain type of person: a critical, intellectual thinker who, instead of sitting passively on the sidelines, can participate in the debates and conversations of your world in an active and empowered way. Ultimately, this course invites you to become a critical thinker who can enter the types of conversations described eloquently by the philosopher Kenneth Burke in the following widely cited passage. Likening the world of intellectual exchange to a never-ending conversation at a party, Burke writes:

You come late. When you arrive, others have long preceded you, and they are engaged in a heated discussion, a discussion too heated for them to pause and tell you exactly what it is about. . . . You listen for a while, until you decide that you have caught the tenor of the argument; then you put in your oar. Someone answers; you answer him; another comes to your defense; another aligns himself against you. . . . The hour grows late, you must depart. And you do depart, with the discussion still vigorously in progress.

Kenneth Burke, The Philosophy of Literary Form

This passage suggestion that stating an argument (putting in your oar) can only be done in conversation with others; that entering the dynamic world of ideas must be done not as isolated individuals but as social beings deeply connected to others.

This ability to enter complex, many-sided conversations has taken on a special urgency in today’s polarized, Red State / Blue State America, where the future for all of us may depend on our ability to put ourselves in the shoes of those who think very differently from us. The central piece of advice in this course—that you listen carefully to others, including those who disagree with you, and then engage with them thoughtfully and respectfully—can help you see beyond your own pet beliefs, which may not be shared by everyone. The mere act of crafting a sentence that begins “Of course, someone might object that” may not seem like a way to change the world; but it does have the potential to jog us out of our comfort zones, to get us thinking critically about our own beliefs, and even to change minds, our own included.