C. W. Williams Health Center: A Community Asset

CASE 16 C. W. Williams Health Center: A Community Asset

The Metrolina Health Center was started by Dr. Charles Warren “C. W.” Williams and several medical colleagues with a $25,000 grant from the Department of Health and Human Services. Concerned about the health needs of the poor and wanting to make the world a better place for those less fortunate, Dr. Williams, Charlotte's first African American to serve on the surgical staff of Charlotte Memorial Hospital (Charlotte's largest hospital), enlisted the aid of Dr. John Murphy, a local dentist; Peggy Beckwith, director of the Sickle Cell Association; and health planner Bob Ellis to create a health facility for the unserved and underserved population of Mecklenburg County, North Carolina. The health facility received its corporate status in 1980. Dr. Williams died in 1982 when the health facility was still in its infancy. Thereafter, the Metrolina Comprehensive Health Center was renamed the C. W. Williams Health Center.

“We're celebrating our fifteenth year of operation at C. W. Williams, and I'm celebrating my first full year as CEO,” commented Michelle Marrs. “I'm feeling really good about a lot of things–we are fully staffed for the first time in two years, and we are a significant player in a pilot program by North Carolina to manage the health care of Medicaid patients in Mecklenburg County (Charlotte area) through private HMOs. We're the only organization that's approved to serve Medicaid recipients that's not an HMO. We have a contract for primary care case management. We're used to providing care for the Medicaid population and we're used to providing health education. It's part of our original mission (see Exhibit 16/1) and has been since the beginning of C. W. Williams.”

Exhibit 16/1: C. W. Williams Health Center Mission, Vision, and Values Statements

Mission

To promote a healthier future for our community by consistently providing excellent, accessible health care with pride, compassion, and respect.

Values

• Respect each individual, patient, and staff member as well as our community as a valued entity that must be treasured.

• Consistently provide the highest quality patient care with pride and compassion.

• Partner with other organizations to respond to the social, health, and economic development needs of our community.

• Operate in an efficient, well-staffed, comfortable environment as an autonomous and financially sound organization.

Vision

Committed to the pioneering vision of Dr. Charles Warren Williams, Charlotte's first Black surgeon, we will move into the twenty-first century promoting a healthier and brighter future for our community. This means:

• C. W. Williams Health Center will offer personal, high-quality, affordable, comprehensive health services that improve the quality of life for all.

• C. W. Williams Health Center, while partnering with other health care organizations, will expand its high-quality health services into areas of need. No longer will patients be required to travel long distances to receive the medical care they deserve. C. W. Williams Health Center will come to them!

• C. W. Williams Health Center will be well managed using state-of-the-art technology, accelerating into the twenty-first century as a leading provider of comprehensive community-based health services.

• C. W. Williams Health Center will be viewed as Mecklenburg County's premier community health agency, providing care with RESPECT:

R eliable health care

E fficient operations

S upportive staff

P ersonal care

E ffective systems

C lean environments

T imely services

Exhibit 16/2: Michelle Marrs, Chief Executive Officer of C. W. Williams Health Center

Michelle Marrs had over 20 years’ experience working in a variety of health care settings and delivery systems. On earning her BS degree, she began her career as a community health educator working in the prevention of alcoholism and substance abuse among youth and women. In 1976 she pursued graduate education at the Harvard School of Public Health and the Graduate School of Education, earning a masters of education with a concentration in administration, planning, and social policy. She worked for the US Public Health Service, Division of Health Services Delivery; the University of Massachusetts Medical Center as director of the Patient Care Studies Department and administrator of the Radiation Oncology Department; the Mattapan Community Health Center (a comprehensive community-based primary care health facility in Boston) as director; and as medical office administrator for Kaiser Permanente. Marrs was appointed chief executive officer of the C. W. Williams Health Center in November 1994.

Michelle continued, “I've been in health care for quite a while but things are really changing rapidly now. The center might be forced to align with one of the two hospitals because of managed care changes. Although we don't want to take away the patient's choice, it might happen. In order for me to do all that I should be doing externally, I need more help internally. I believe we should have a director of finance. We have a great opportunity to buy another location so that we can serve more patients, but this is a relatively unstable time in health care. Buying another facility would be a stretch financially, but the location would be perfect. The asking price does seem high, though…” (Exhibit 16/2 contains a biographical sketch of Ms. Marrs.)

Community Health Centers1

When the nation's resources were mobilized during the early 1960s to fight the War on Poverty, it was discovered that poor health and lack of basic medical care were major obstacles to the educational and job training progress of the poor. A system of preventive and comprehensive medical care was necessary to battle poverty. A new health care model for poor communities was started in 1963 through the vision and efforts of two New England physicians–Count Geiger and Jack Gibson of the Tufts Medical School–to open the first two neighborhood health centers in Mound Bayou, in rural Mississippi, and in a Boston housing project.

In 1966, an amendment to the Economic Opportunity Act formally established the Comprehensive Health Center Program. By 1971, a total of 150 health centers had been established. By 1990, more than 540 community and migrant health centers at 1,400 service sites had received federal grants totaling $547 million to supplement their budgets of $1.3 billion. By 1996, the numbers had increased to 700 centers at 2,400 delivery sites providing service to over 9 million people.

Community health centers had a public health perspective; however, they were similar to private practices staffed by physicians, nurses, and allied health professionals. They differed from the typical medical office in that they offered a broader range of services, such as social services and health education. Health centers removed the financial and nonfinancial barriers to health care. In addition, health centers were owned by the community and operated by a local volunteer governing board. Federally funded health centers were required to have patients as a majority of the governing board. The use of patients to govern was a major factor in keeping the centers responsive to patients and generating acceptance by them. Because of the increasing complexity of health care delivery, many board members were taking advantage of training opportunities through their state and national associations to better manage the facility.

Exhibit 16/3: Ethnicity of Urban and Rural Health Center Patients

| Urban Health Center Patients | Rural Health Center Patients | ||

| African American/Black | 37.0% | African American/Black | 19.6% |

| White/Non-Hispanic | 29.9% | White/Non-Hispanic | 49.3% |

| Native American | 0.8% | Native American | 1.1% |

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 3.2% | Asian/Pacific Islander | 2.9% |

| Hispanic/Latino | 27.2% | Hispanic/Latino | 26.5% |

| Other | 1.9% | Other | 0.6% |

Community Health Centers Provide Care for the Medically Underserved

Federally subsidized health centers must, by law, serve populations that are identified by the Public Health Service as medically underserved. Half of the medically underserved population lived in rural areas where there were few medical resources. The other half were located in economically depressed inner-city communities where individuals lived in poverty, lacked health insurance, or had special needs such as homelessness, AIDS, or substance abuse. Approximately 60 percent of health center patients were minorities in urban areas whereas 50 percent were white/non-Hispanics in rural areas (see Exhibit 16/3).

Typically, 50 percent of health center patients did not have private health insurance; nor did they qualify for public health insurance (Medicaid or Medicare). That compared to 13.4 percent of the US population that was uninsured (see Exhibit 16/4). Over 80 percent of health center patients had incomes below the federal poverty level ($28,700 for a family of four in 1994). Most of the remaining 20 percent were between 100 percent and 200 percent of the federal poverty level.

Exhibit 16/4: Insurance Status of US Health Center Patients, C. W. Williams Health Center Patients, the US Population, and North Carolina Population

| Health Center Patients | US Population | North Carolina Population | C. W. Williams Health Center Patients | |

| Uninsured | 42.7% | 13.4% | 14% | 21% |

| Private Insurance | 13.9% | 63.2% | 64% | 10% |

| Public Insurance | 42.9% | 23.4% | 22% | 69% |

* This case was written by Linda E. Swayne, The University of North Carolina at Charlotte, and Peter M. Ginter, University of Alabama at Birmingham. It is intended as a basis for classroom discussion rather than to illustrate either effective or ineffective handling of an administrative situation. Used with permission from Linda Swayne.

Community Health Centers are Cost Effective

Numerous national studies have indicated that the kind of ongoing primary care management provided by community health centers resulted in significantly lowered costs for inpatient hospital care and specialty care. Because illnesses were diagnosed and treated at an earlier stage, more expensive care interventions were often not needed. Hospital admission rates were 22 to 67 percent lower for health center patients than for community residents. A study of six New York city and state health centers found that Medicaid beneficiaries were 22 to 30 percent less costly to treat than those not served by health centers.2 A Washington state study found that the average cost to Medicaid per hospital bill was $49 for health center patients versus $74 for commercial sector patients.3 Health center indigent patients were less likely to make emergency room visits–a reduction of 13 percent overall and 38 percent for pediatric care. In addition, defensive medicine (the practice of ordering every and all diagnostic tests to avoid malpractice claims) was less frequently used. Community health center physicians had some of the lowest medical malpractice loss ratios in the nation.

Not only were community health centers cost efficient, patients were highly satisfied with the care received. A total of 96 percent were satisfied or very satisfied with the care they received, and 97 percent indicated they would recommend the health center to their friends and families.4 Only 4 percent were not so satisfied, and only 3 percent would not recommend their health center to others.

Movement to Managed Care

In 1990, a little over 2 million Medicaid beneficiaries were enrolled in managed care plans; in 1993 the number had increased to 8 million; and in 1995 over 11 million Medicaid beneficiaries were enrolled. Medicaid beneficiaries and other low-income Americans had higher rates of illness and disability than others, and thus accumulated significantly higher costs of medical care.5

C. W. Williams Health Center

C. W. Williams was beginning to recognize the impact of managed care. Like much of the South, the Carolinas had been slow to accept managed care. The major reasons seemed to be the rural nature of many Southern states, markets that were not as attractive to major managed care organizations, dominant insurers that continued to provide fee-for-service ensuring choice of physicians and hospitals, and medical inflation that accelerated more slowly than in other areas. Major changes began to occur, however, beginning in 1993; by 1996 managed care was being implemented in many areas at an accelerated pace.

Challenges for C. W. Williams

Michelle reported, “One of my greatest challenges has been how to handle the changes imposed by the shift from a primarily fee-for-service to a managed care environment. Local physicians who in the past had the flexibility, loyalty, and availability to assist C. W. Williams by providing part-time assistance or volunteer efforts during the physician shortage are now employed by managed care organizations or involved in contractual relationships that prohibit them from working with us. The few remaining primary care solo or small group practices are struggling for survival themselves and seldom are available to provide patient sessions or assist with our hospital call-rotation schedule. The rigorous call-rotation schedule of a small primary care facility like C. W. Williams is frequently unattractive to available physicians seeking opportunities, even when a market competitive compensation package is offered. Many of these physician recruitment and retention issues are being driven by the rapid changes brought on by the impact of managed care in the local community. It is a real challenge to recruit physicians to provide the necessary access to medical care for our patients.”

She continued, “My next greatest challenge is investment in technology to facilitate this transition to managed care. Technology is expensive, yet I know it is crucial to our survival and success. We also need more space, but I don't know if this is a good time for expansion.”

She concluded, “One of the pressing and perhaps most difficult efforts has been the careful and strategic consideration of the need to affiliate to some degree with one of the two area hospitals in order to more fully integrate and broaden the range of services to patients of our center. Although a decision has not been made at this juncture, the organization has made significant strides to comprehend the needs of this community, consider the pros and cons of either choice, and continue providing the best care possible under some very difficult circumstances.”

Hospital Affiliation

Traditionally, the patients of C. W. Williams Health Center that needed hospitalization were admitted to Charlotte Memorial Hospital, a large regional hospital that was designated at the Trauma 1 level–one of five designated by the state of North Carolina to handle major trauma cases 24 hours a day, 7 days per week (full staffing) as well as perform research in the area of trauma. Uncompensated inpatient care was financed by the county. Charlotte Memorial became Carolinas Medical Center (CMC) in 1984 when it began a program to develop a totally integrated system. In 1995, C. W. Williams provided Carolinas Medical Center with more than 3,000 patient bed days; however, the patients were usually seen by their regular C. W. Williams physicians. As Carolinas Medical Center purchased physician practices (over 300 doctors were employed by the system) and purchased or managed many of the surrounding community hospitals, some C. W. Williams patients became concerned that CMC would take over C. W. Williams and that their community health center would no longer exist.

“My preference is that our patients have a choice of where they would prefer to go for hospitalization. Our older patients expect to go to Carolinas Medical, but many of our middle-aged patients have expressed a preference for Presbyterian. Both hospitals have indicated an interest in our patients,” according to Michelle. She continued, “We may not really have a choice, however. We recently received information that reported the 12 largest hospitals in the state, including the teaching hospitals–Duke, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Carolinas Medical Center, and East Carolina–have formed a consortium and will contract with the state to pay for Medicaid patients. At the same time all 20 of the health centers in the state–including us at C. W. Williams–are cooperating to develop a health maintenance organization. We expect to gain approval for the HMO by July 1997. Since 60 percent of our patients are Medicaid, if the state contracts with the new consortium, then we will be required to send our patients to Carolinas Medical Center.”

Services

C. W. Williams Health Center provides primary and preventive health services including: medical, radiology, laboratory, pharmacy, subspecialty, and inpatient managed care; health education/promotion; community outreach; and transportation to care (Exhibit 16/5 lists all services). The center was strongly linked to the Charlotte community, and it worked with other public and private health services to coordinate resources for effective patient care. No one was denied care because of an inability to pay. A little over 20 percent of the patients at C. W. Williams were uninsured.

The full-time staff included five physicians, two physician assistants (PAs), two nurses, one X-ray technician, one pharmacist, and a staff of 28. Of the five physicians, one was an internist, two were in family practice, and two were pediatricians. The PAs “floated” to work wherever help was most needed. With the help of one assistant, the pharmacist filled more than 20,000 prescriptions annually.

Patients at C. W. Williams

All first-time patients at C. W. Williams were asked what type of insurance they had. If they had some type of insurance–private, Medicare, Medicaid–an appointment was immediately scheduled. If the new patient had no insurance, he or she was asked if they would be interested in applying for the C. W. Williams discount program (the discount could amount to as much as 100 percent, but every person was asked to pay something). The discount was based on income and the number of people in the household. If the response was “no,” the caller was informed that payment was expected at the time services were rendered. Visa, MasterCard, cash, and personal check (with two forms of identification) were accepted. At C. W. Williams, all health care was made affordable.

Exhibit 16/5: C. W. Williams Health Center Services

Primary Care and Preventive Services

Diagnostic Laboratory

Diagnostic X-ray (basic)

Pharmacy

EMS (crash cart and CPR-trained staff)

Family Planning

Immunizations (MD-directed as well as open clinic–no relationship required)

Prenatal Care and Gynecology

Health Education

Parenting Education

Translation Services

Substance Abuse and Counseling

Nutrition Counseling

Diagnostic Testing:

HIV

Mammogram

Pap Smears

TB Testing

Vision/Hearing Testing

Lead Testing

Pregnancy Test

Drug Screening

C. W. Williams made reminder calls to the patient's home (or neighbor's or relative's telephone) several days prior to the appointment. When patients arrived at the center, they provided their name to the nurse at the front reception desk and then took a seat in a large waiting room. The pharmacy window was near the front door for the convenience of patients who were simply picking up a prescription. The reception desk, pharmacy, and waiting room occupied the first floor.

When the patient's name was called, he or she was taken by elevator to the second floor where there were ten examination rooms. After seeing the physician, physician assistant, or nurse, the patient was escorted back down the elevator to the pharmacy if a prescription was needed and then to the reception desk to pay. Pharmaceuticals were discounted and a special program by Pfizer Pharmaceuticals provided over $60,000 worth of drugs in 1995 for medically indigent patients.

The center's patient population was 64 percent female between the ages of 15 and 44 (see Exhibit 16/6). Nearly 80 percent of patients were African Americans, 18 percent were white, and 2 percent were other minorities. Patients were quite satisfied with the services provided as indicated in patient surveys conducted by the center. Paralleling national studies, 97 percent of C. W. Williams patients would recommend the center to family or friends. Selected service indicators by rank from the patient satisfaction study are included as Exhibit 16/7.

Exhibit 16/6: C. W. Williams Health Center Patients by Age and Sex

| Females | 1991 | 1992 | 1993 | 1994 | 1995 |

| <1 | 343 | 408 | 263 | 198 | 101 |

| 1–4 | 434 | 552 | 692 | 647 | 417 |

| 5–11 | 322 | 572 | 494 | 641 | 658 |

| 12–14 | 376 | 197 | 150 | 148 | 124 |

| 15–17 | 361 | 168 | 146 | 121 | 92 |

| 18–19 | 264 | 152 | 85 | 82 | 67 |

| 20–34 | 749 | 1,250 | 967 | 964 | 712 |

| 35–44 | 869 | 617 | 479 | 532 | 467 |

| 45–64 | 583 | 567 | 617 | 658 | 658 |

| 65+ | 400 | 488 | 531 | 527 | 524 |

| 4,701 | 4,971 | 4,424 | 4,518 | 3,820 | |

| Males | |||||

| <1 | 367 | 471 | 328 | 199 | 119 |

| 1–4 | 439 | 516 | 707 | 625 | 410 |

| 5–11 | 440 | 644 | 598 | 846 | 738 |

| 12–14 | 171 | 175 | 128 | 120 | 104 |

| 15–17 | 180 | 133 | 79 | 76 | 155 |

| 18–19 | 126 | 67 | 28 | 23 | 69 |

| 20–34 | 296 | 389 | 219 | 187 | 126 |

| 35–44 | 313 | 296 | 182 | 205 | 132 |

| 45–64 | 229 | 316 | 273 | 294 | 235 |

| 65+ | 151 | 248 | 190 | 190 | 181 |

| 2,712 | 3,255 | 2,732 | 2,765 | 2,269 | |

| Total | 7,413 | 8,226 | 7,156 | 7,283 | 6,089 |

Exhibit 16/7: Patient Satisfaction Study

| Rank | Selected Service Indicators | Mean Score |

| Helpfulness/attitudes of medical staff | 3.82 | |

| Clean/comfortable/convenient facility | 3.65 | |

| Relationship with physician/nurse | 3.58 | |

| Quality of health services | 3.28 | |

| Ability to satisfy all medical needs | 3.20 | |

| Helpfulness/attitudes of nonmedical staff | 2.72 |

C. W. Williams Organization

The center was managed by a board of directors, responsible for developing policy and hiring the CEO.

Board of Directors

The federal government required that all community health centers have a board of directors that was made up of at least 51 percent patients or citizens who lived in the community. The board chairman of C. W. Williams, Mr. Daniel Dooley, was a center patient. C. W. Williams had a board of 15, all of whom were African Americans and four of whom were patients and out of the workforce. Two members of the board were managers/directors from the Public Health Department (which was under the management of CMC). There were two other health professionals–a nurse and a physician. Other board members included a CPA, a financial planner, an insurance agent, a vice president for human resources, an executive in a search firm, and a former professor of economics. A majority of the board had not had a great deal of exposure to the changes occurring in the health care industry (aside from their own personal situations); nor were they trained in strategic management.

The Staff

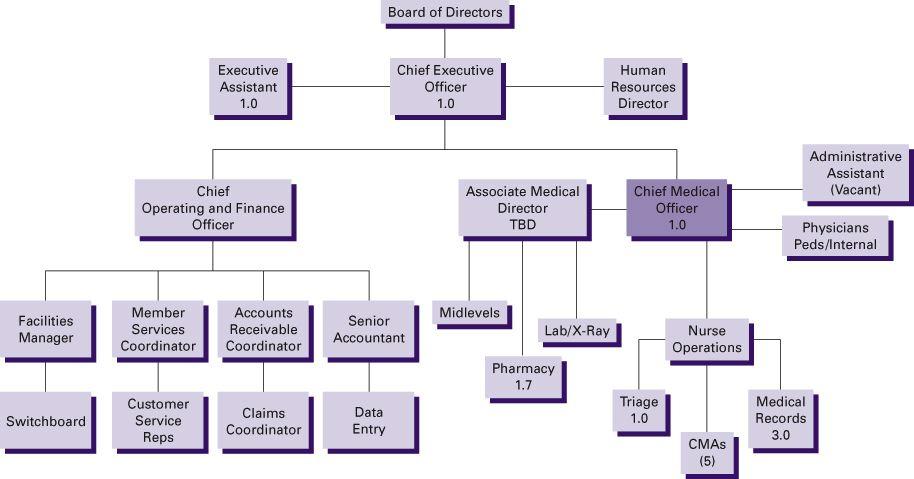

The center was operated by Michelle Marrs as CEO, who had an operations officer and medical director reporting to her (see Exhibit 16/8 for an organization chart).

Eventually the director of finance, who had worked at the center for over ten years, resigned. “She was offered another position within C. W. Williams,” said Michelle, “but she declined to take it. Frankly, I have to have someone with greater expertise in finance. With capitation on the horizon, we need to do some very critical planning to better manage our finances and make sure we are receiving as much reimbursement from Washington as we are entitled.”

There were some disagreements between the board and Ms. Marrs over responsibilities. Employees frequently appealed to the chairman and other members of the board when they felt that they had not been treated fairly. Ms. Marrs would prefer the board to be more involved in setting strategic direction for C. W. Williams. “A two-year strategic plan was developed late in 1995 that has not been moved along, embraced, and further developed. Committees have not met on a regular basis to actualize stated objectives.”

C. W. Williams Was Financially Strong

The center received an increasing amount of federal grant money for the first ten years of its operation as the number of patients grew, but leveled off as most government allocations were reduced (see Exhibit 16/9). Although the amount collected from Medicare was increasing, the amount collected compared with the full charge was decreasing (see Exhibit 16/10). Exhibits 16/11 to 16/14 provide details of the financial situation.

Exhibit 16/8: Metrolina Comprehensive Health Center, Inc. dba C. W. Williams Health Center

Carolina ACCESS–A Pilot Program

In fiscal year 1994 (July 1, 1994 to June 30, 1995), North Carolina served more than 950,000 Medicaid recipients at a cost of over $3.5 billion. The aged, blind, and disabled accounted for 26 percent of the eligibles and 65 percent of the expenditures. Families and children accounted for 74 percent of the eligibles and 35 percent of the expenditures. Services were heavily concentrated in two areas: inpatient hospital–accounting for 20 percent of expenses–and nursing-facility/intermediate care/mentally retarded services–accounting for 34 percent of expenses. Mecklenburg County had the highest number of eligibles within the state at 50,849 people, representing 7 percent of the Medicaid population.

What started out in 1986 as a contract with Kaiser Permanente to provide medical services for recipients of Aid to Families with Dependent Children in four counties became a complex mixture of three models of managed care. Carolina ACCESS was North Carolina Medicaid's primary care case management model of managed care. It began a pilot program named “Health Care Connections” in Mecklenburg County on June 1, 1996.

Exhibit 16/9: C. W. Williams Funding Sources

| Funding Source | 1991 | 1992 | 1993 | 1994 | 1995 |

| Grant (Federal) | 740,000 | 666,524 | 689,361 | 720,584 | 720,584 |

| Medicare | 152,042 | 157,891 | 258,104 | 260,389 | 301,444 |

| Medicaid | 381,109 | 453,712 | 641,069 | 562,380 | 456,043 |

| Third-Party Pay | 25,673 | 14,128 | 84,347 | 90,253 | 51,799 |

| Uninsured Self-Pay | 300,748 | 441,508 | 174,992 | 262,817 | 338,272 |

| Grant (Miscellaneous) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 11,500 | 48,000 |

| Total | 1,599,572 | 1,733,763 | 1,847,873 | 1,907,923 | 1,916,142 |

Exhibit 16/10: Funding Accounts Receivable

| 1994 | 1995 | ||||

| Full Charge | Amount Collected | Full Charge | Amount Collected | ||

| Medicare | 436,853 | 260,389 | 369,306 | 301,444 | |

| Medicaid | 914,212 | 562,380 | 725,175 | 456,043 | |

| Insured | 99,202 | 90,253 | 61,021 | 51,799 | |

| Patient Fees | 899,055 | 262,817 | 754,864 | 338,272 | |

Exhibit 16/11: C. W. Williams Health Center Balance Sheets

| 1992–1993 | 1993–1994 | 1994–1995 | 1995–1996 | ||

| Assets | |||||

| Current Assets | |||||

| Cash | 280,550 | 335,258 | 339,459 | 132,925 | |

| Certificates of Deposit | 23,413 | 24,496 | 25,446 | 529,826 | |

| Accounts Receivable (net) | 213,815 | 285,934 | 202,865 | 160,230 | |

| Accounts Receivable (other) | 5,661 | 4,721 | 2,936 | 10,069 | |

| Security Deposits | 1,847 | 97 | -0- | -0- | |

| Notes Receivable | -0- | -0- | 29,825 | 10,403 | |

| Inventory | 26,191 | 23,777 | 30,217 | 26,844 | |

| Prepaid Loans | 12,087 | 21,605 | 9,722 | 11,159 | |

| Investments | 269 | 269 | 269 | 51,628 | |

| Total Current Assets | 563,833 | 696,157 | 640,739 | 933,084 | |

| Property and Equipment | |||||

| Land | 10,000 | 10,000 | 10,000 | 10,000 | |

| Building | 311,039 | 311,039 | 311,039 | 311,039 | |

| Building Renovations | 904,434 | 904,434 | 909,754 | 915,949 | |

| Equipment | 282,333 | 312,892 | 328,063 | 387,178 | |

| Less Depreciation | (393,392) | (452,432) | (523,384) | (597,275) | |

| Total Property and Equipment | 1,114,414 | 1,085,933 | 1,035,472 | 1,026,891 | |

| Total Assets | 1,678,247 | 1,782,090 | 1,676,211 | 1,959,975 | |

| Liabilities and Net Assets | |||||

| Liabilities | |||||

| Accounts Payable | 11,066 | 31,582 | 13,136 | 34,039 | |

| Vacation Expense Accounts | 36,694 | 42,857 | 19,457 | 28,144 | |

| Deferred Revenue | 42,641 | 37,910 | 43,400 | 59,433 | |

| Total Liabilities | 90,401 | 112,349 | 75,993 | 121,616 | |

| Net Assets | |||||

| Unrestricted | 1,838,350 | ||||

| Temporary Restricted | -0- | -0- | -0- | -0- | |

| Total Net Assets | 1,587,846 | 1,669,741 | 1,600,218 | 1,838,350 | |

| Total Liabilities and Net Assets | 1,678,247 | 1,782,090 | 1,676,211 | 1,959,976 | |

Health Care Connections

The state of North Carolina wanted to move 42,000 Mecklenburg County Medicaid recipients into managed care. The state contracted with six health plans and C. W. Williams, as a federally qualified health center, to serve the Mecklenburg County Medicaid population. Because one organization was dropped from the program, Medicaid recipients were to choose one of the following plans to provide their health care:

• Atlantic Health Plans (type: HMO; hospital affiliation: Carolinas Medical Center, University Hospital, Mercy Hospital, Mercy South, Union Regional Medical, Kings Mountain Hospital).

• Kaiser Permanente (type: HMO; hospital affiliation: Presbyterian Hospital, Presbyterian Hospital–Matthews, Presbyterian Orthopedic, Presbyterian Specialty Hospital).

• Maxicare North Carolina, Inc. (type: HMO; hospital affiliation: Presbyterian Hospital, Presbyterian Hospital–Matthews, Presbyterian Orthopedic, Presbyterian Specialty Hospital).

• Optimum Choice/Mid-Atlantic Medical (type: HMO; hospital affiliation: Presbyterian Hospital, Presbyterian Hospital–Matthews, Presbyterian Orthopedic, Presbyterian Specialty Hospital).

• The Wellness Plan of NC, Inc. (type: HMO; hospital affiliation: Carolinas Medical Center, University Hospital, Mercy Hospital, Mercy South, Union Regional Medical, Kings Mountain Hospital).

• C. W. Williams Health Center (type: partially federally funded, community health center; hospital affiliation: Carolinas Medical Center, University Hospital, Mercy Hospital, Mercy South, Union Regional Medical, Kings Mountain Hospital or Presbyterian Hospital, Presbyterian Hospital–Matthews, Presbyterian Orthopedic, Presbyterian Specialty Hospital).

Exhibit 16/12: Statement of Support, Revenue, Expenses, and Change in Fund Balances

| 1992–1993 | 1993–1994 | 1994–1995 | 1995–1996 | |

| Contributed Support and Revenue | ||||

| Contributed | 720,712 | 720,584 | 732,584 | 768,584 |

| Earned Revenue | ||||

| Patient Fees | 1,213,919 | 1,186,497 | 1,183,904 | 1,129,030 |

| Medicare 465,248 | ||||

| Contributions 5,676 | ||||

| Interest Income | 7,228 | 9,666 | 12,567 | 14,115 |

| Dividend Income 2,387 | ||||

| Rental Income 1,980 | ||||

| Miscellaneous Income | 5,962 | 5,941 | 4,772 | 11,055 |

| Total Earned | 1,227,109 | 1,202,104 | 1,201,243 | 1,629,491 |

| Total Contributed Support and Revenue | 1,947,821 | 1,922,688 | 1,933,827 | 2,398,075 |

| Expenses | ||||

| Program | 1,782,312 | 1,840,447 | 2,002,633 | 2,157,768 |

| Other | 442 | 349 | 217 | 2,166 |

| Total Expenses | 1,782,754 | 1,840,796 | 2,002,850 | 2,159,934 |

| Increase (decrease) in Net Assets | 165,062 | 81,892 | (69,523) | 238,141 |

| Net Assets (beginning of year) | 1,310,155 | 1,587,849 | 1,669,741 | 1,600,218 |

| Adjustment | 112,629* | -0- | -0- | -0- |

| Net Assets (end of year) | 1,587,846 | 1,669,741 | 1,600,218 | 1,838,359 |

* Federal grant funds earned but not drawn down in prior years were not recognized as revenue. The error had no effect on net income for fiscal year ended March 31, 1992.

Exhibit 16/13: Statement of Functional Expenditures, Fiscal Year Ended March 31

| 1992–1993 | 1993–1994 | 1994–1995 | 1995–1996 | |

| Personnel | ||||

| Salaries | 937,119 | 1,016,194 | 1,102,373 | 1,181,639 |

| Benefits | 190,300 | 210,228 | 210,674 | 211,705 |

| Total | 1,127,419 | 1,226,422 | 1,313,047 | 1,393,344 |

| Other | ||||

| Accounting | 5,250 | 5,985 | 6,397 | 7,200 |

| Bank Charges | 840 | 300 | 213 | 1,001 |

| Building Maintenance | 38,842 | 54,132 | 49,586 | 53,828 |

| Consultants | 26,674 | 2,733 | 39,565 | 44,923a |

| Contract MDs | -0- | -0- | -0- | 87,159 |

| Dues/Publications/Conferences | 17,371 | 21,655 | 22,066 | 24,258 |

| Equipment Maintenance | 28,732 | 27,365 | 30,402 | 27,352 |

| Insurance | 15,182 | 3,146 | 3,215 | 3,292 |

| Legal Fees | 688 | 2,774 | 3,652 | 3,582 |

| Marketing | 6,358 | 1,958 | 5,734 | 15,730 |

| Patient Services | 28,959 | 28,222 | 35,397 | 43,815 |

| Pharmacy | 271,542 | 237,761 | 225,762 | 188,061 |

| Physician Recruiting | 14,171 | 32,929 | 56,173 | 21,395 |

| Postage | 8,435 | 11,622 | 10,019 | 14,182 |

| Printing | 729 | 963 | 2,405 | 9,696 |

| Supplies | 73,020 | 62,828 | 72,977 | 84,064 |

| Telephone | 16,755 | 17,967 | 20,914 | 25,002 |

| Travel–Board | 2,713 | 1,202 | 4,977 | 3,476 |

| Travel–Staff | 13,889 | 14,576 | 12,631 | 15,978 |

| Utilities | 15,782 | 18,305 | 16,548 | 16,536 |

| Total Other | 585,932 | 546,423 | 618,633 | 690,530 |

| Total Personnel and Other | 1,713,351 | 1,772,845 | 1,931,680 | 2,083,874 |

| Depreciation | (68,966) | (67,604) | (70,952) | (73,891) |

| Total Expenses | 1,782,317 | 1,840,449 | 2,002,632 | 2,157,765 |

a Includes contracted medical director.

An integral part of the selection process was the use of a health benefits advisor to assist families in choosing the appropriate plan. By law, none of the organizations was permitted to promote its plan to Medicaid recipients. Rather, the Public Consulting Group of Charlotte was awarded the contract to be an independent enrollment counselor to assist Medicaid recipients in their choices of health care options.

“More than 33,000 of the Medicaid recipients were women and children. Sixty percent of the group had no medical relationship. Slightly over 50 percent of C. W. Williams's patients are Medicaid recipients,” said Michelle Marrs. See Exhibit 16/15 for C. W. Williams users by pay source.

Exhibit 16/14: C. W. Williams Health Center Statement of Cash Flows, Fiscal Year Ended March 31

| Net Cash Flow from Operations | 1992–1993 | 1993–1994 | 1994–1995 | 1995–1996 |

| Increase in Net Assets | 165,062 | 81,892 | (69,523) | 238,141 |

| Noncash Income Expense Depreciation | 68,966 | 67,604 | 70,952 | 73,891 |

| Increase in Deposits | (1,750) | 1,750 | -0- | -0- |

| Decrease in Receivables | (86,620) | (71,179) | 55,028 | 65,328 |

| (Increase) in Prepaid Expenses | (2,277) | (9,518) | 11,980 | (1,437) |

| (Increase) Decrease in Inventory | (4,105) | 2,414 | (6,440) | 3,373 |

| Increase in Payables | 14,094 | 20,516 | (18,445) | 20,903 |

| Increase (Decrease) in Vacation Expense Accrual | (8,583) | 6,163 | (23,400) | 8,688 |

| (Increase) in Notes Receivable | -0- | -0- | -0- | (10,403) |

| Increase in Deferred Revenue | (2,992) | (4,731) | 5,490 | 16,032 |

| Net Cash Flow from Operations | 141,795 | 94,911 | 25,642 | 414,516 |

| Cash Flow from Investing in Fixed Assets | (52,547) | (39,120) | (20,491) | (65,311) |

| Purchase Marketable Securities | -0- | -0- | -0- | (51,359) |

| Net Cash Used by Investments | (52,547) | (39,120) | (20,491) | (116,670) |

| Net Cash from Financing Activities | 112,629 | -0- | -0- | -0- |

| Increase in Cash | 201,877 | 55,791 | 5,151 | 297,846 |

| Cash + Cash Equivalents | ||||

| Beginning of Year April 1 | 130,274 | 332,151 | 387,942 | 393,093 |

| End of Year March 31 | 332,151 | 387,942 | 393,093 | 690,939 |

“We have about 8,000 patients coming to us for about 30,000 visits,” according to Michelle (see Exhibit 16/16). “So there are approximately 4,000 people who currently come to us for health care that are now required to choose a health plan. The state decided that an independent agency had to sign people up so that there would be no ‘bounty’ hunting for enrollees. In the first month, about 2,300 Medicaid recipients enrolled in the pilot program. Almost half of the people who signed up chose Kaiser Foundation Health Plan. It has a history of serving Medicaid patients. We received the next highest number of enrollees, because we too have a history of serving this market. We had 402 enrollees during that first month. Of those, only 38 were previous patients. What we don't know yet is whether we have lost any patients to other programs. The lack of up-to-date information is frustrating. We need a better information system.”

Michelle continued, “We decided that we could provide care for up to 8,000 Medicaid patients at C. W. Williams. I embrace managed care for a number of reasons: patients must choose a primary care provider, patients will be encouraged to take an active role in their health care, and there will be less duplication of medical services and costs. In the past, some doctors have shied away from Medicaid patients because they didn't want to be bothered with the paperwork, the medical services weren't fully compensated, and Medicaid patients tended to have numerous health problems.”

Exhibit 16/15: Users by Pay Source

| Source | Percent of Users | Number of Users | Income to C.W. Williams | Number of Encounters |

| 1994–1995 | ||||

| Medicare | 13% | 791 | 301,444 | 2,392 |

| Medicaid | 56% | 3,410 | 456,043 | 10,305 |

| Full Pay | 10% | 609 | 318,424 | 1,840 |

| Uninsured | 21% | 1,279 | 42,421 | 3,865 |

| 6,089 | 1,118,332 | 18,402 | ||

| 1993–1994 | ||||

| Medicare | 12% | 1,037 | 195,352 | 2,880 |

| Medicaid | 53% | 4,579 | 585,446 | 12,720 |

| Full Pay | 11% | 950 | 178,525 | 2,640 |

| Uninsured | 24% | 2,074 | 101,569 | 5,760 |

| 8,640 | 1,060,892 | 24,000 | ||

| 1992–1993 | ||||

| Medicare | 10% | 853 | 189,927 | 2,304 |

| Medicaid | 36% | 3,072 | 401,355 | 8,294 |

| Full Pay | 10% | 853 | 158,473 | 2,304 |

| Uninsured | 44% | 3,755 | 186,708 | 10,138 |

| 8,533 | 936,463 | 23,040 | ||

| 1991–1992 | ||||

| Medicare | 20% | 1,614 | 162,980 | 4,032 |

| Medicaid | 30% | 2,419 | 312,680 | 6,048 |

| Full Pay | 10% | 806 | 157,101 | 2,016 |

| Uninsured | 40% | 3,225 | 159,855 | 8,064 |

| 8,064 | 792,616 | 20,160 | ||

Exhibit 16/16: C. W. Williams Health Center Patient Visits

| Primary Care Visits | |

| Internal Medicine | 8,248 |

| Family Practice | 4,573 |

| Pediatrics | 2,643 |

| Gynecology | 236 |

| Midlevel Practitioners | 3,609 |

| Total | 19,309 |

| Subspecialty/Ancillary Service Visits | |

| Podiatry | 82 |

| Mammography | 101 |

| Immunizations | 1,766 |

| Perinatal | 429 |

| X-ray | 1,152 |

| Dental | 17 |

| Pharmacy Prescriptions | 20,868 |

| Hospital | 1,762 |

| Laboratory | 13,103 |

| Health Education | 412 |

| Other Medical Specialists | 2,032 |

| Total | 40,724 |

“There are seven different companies that applied and were given authority to provide health care for Medicaid recipients in Mecklenburg County. Although I understand one had to withdraw, we are the only one that is not an HMO. Although we don't provide hospitalization, we do provide for patients’ care whether they need an office visit or to be hospitalized. Our physicians provide care while the patient is in the hospital.”

She continued, “Medicaid beneficiaries have to be recertified every six months. We are three months into the sign-up process or approximately halfway. Kaiser has enrolled the highest number, about one-third of the beneficiaries (see Exhibit 16/17). We have enrolled over 12 percent. The independent enrollment counselor is responsible for helping Medicaid recipients enroll during the initial 12 months. I expect the numbers to dwindle for the last six months of that time period. Changes will primarily come from new patients to the area and patients who are unhappy with their initial choice.”

Medicaid patients were going to be a challenge for managed care. Because many of them were used to going to the emergency room for care, they were not in the habit of making or keeping appointments. Some facilities overbooked appointments to try to utilize medical staff efficiently; however, the practice caused very long waits at times. Other complicating factors included lack of telephones for contacting patients for reminder calls or physician follow-ups, lack of transportation, the number of high-risk patients as a result of poverty or lifestyle factors, and patients that did not follow doctors’ orders.

Health Connection Enrollment

Medicaid recipients were required to be recertified every six months in the state of North Carolina. During this process, a time was allocated for the Public Consulting Group of Charlotte to make a presentation about the managed care choices available. The presentation included a discussion of:

• managed care and HMOs and how they were similar to and different from previous Medicaid practices;

• benefits of Health Care Connections such as having a medical home, a 24-hour, seven-day-a-week hotline to ask questions about medical care, physician choice, and plan choice; and

• methods to choose a plan based on wanting to use a doctor that the patient had used before, hospital choice (some plans were associated with a specific hospital), and location (for easy access).

Exhibit 16/17: ACCESS Enrollment Data for the Week Ended September 6, 1996

| Atlantic | Kaiser Permanente | Maxi-care | Optimum Choice | Wellness Plan | C. W. Williams | Total | |

| Week Totals | 229 | 347 | 66 | 114 | 189 | 124 | 1,069 |

| Month-to-date | 229 | 347 | 66 | 114 | 189 | 124 | 1,069 |

| Year-to-date | 3,708 | 5,384 | 1,164 | 1,507 | 2,238 | 2,016 | 16,017 |

| Project-to-date | 3,708 | 5,384 | 1,164 | 1,507 | 2,238 | 2,016 | 16,017 |

If Medicaid recipients did not choose a plan that day, they had ten working days to call in on the hotline to choose a plan. If they had not done so by that deadline, they were randomly assigned to a plan. Public Consulting Group's health benefits advisors (HBAs) made the presentations and then assisted each individual in determining what choice he or she would like to make and filling out the paperwork. More than 80 percent of the Medicaid recipients who went through the recertification process and heard the presentation decided on site. Most others called back on the hotline after more carefully studying the information. About 3 percent were randomly assigned because they did not select a plan.

New Medicaid recipients were provided individualized presentations because they tended to be new to the community, had recently developed a health problem, or were pregnant. Because they might have less information than those who had been “in the system” for some time, it took a more detailed explanation from the HBA.

HBAs presented the information in a fair, factual, and useful manner for session attendees. For the first several months they attempted to thoroughly explain the difference between an HMO and a “partially federally funded community health center,” but the HBAs decided it was too confusing to the audience and did not really make a difference in their health care. For the past month they explained “managed care” more carefully and touched lightly on HMOs. C. W. Williams was presented as one of the choices, although some of the HBAs mentioned that it was the only choice that had evening and weekend hours for appointments.

Strategic Plan for C. W. Williams

With the help of Michelle Marrs, the C. W. Williams Board of Directors was beginning to develop a strategic plan. Exhibit 16/18 provides the SWOT analysis that was developed. “Part of our strategic plan was to go to the people–make it easier for our patients to visit C. W. Williams by establishing satellite clinics. We recently became aware of a building that is for sale that would meet our needs. The owner would like to sell to us. He's older and likes the idea that the building will ‘do some good for people,’ but he's asking $479,000. The location is near a large number of Medicaid beneficiaries plus a middle-class area of minority patients that could add to our insured population. I just don't know if we should take the risk to buy the building. We own our current building and have no debt. We are running out of space at C. W. Williams. We have two examination rooms for each physician and all patients have to wait on the first floor and then be called to the second floor when a room becomes free. I know that ideally for the greatest efficiency we should have three exam rooms for each doctor.”

Exhibit 16/18: C. W. Williams Health Center SWOT Analysis

| Strengths | Weaknesses |

| Community-based business | Need for deputy director |

| Primary care provider with walk-in component | Lack of RN/triage director |

| Large patient base | Staffing and staffing pattern |

| Fast, discounted pharmacy | Managed care readiness |

| Cash reserve | Number of providers |

| Laboratory/X-ray | Recruitment and retention |

| Clean facility in good location | Limited referrals |

| Satellites | Limited services |

| Good reputation with community and funders | No social worker/nutritionist/health educator |

| Resources for disabled patients | No on-site Medicaid eligibility |

| Strong leadership/management | Weak relationship with community MDs |

| Growth potential | Limited hours of operation |

| Property owned with good parking | Transportation |

| Excellent quality of care | Organizational structure |

| Culturally sensitive staff | Management information systems |

| Nice environment | Market share at risk of erosion |

| Dedicated board and staff | Staff orientation to managed care |

Opportunities

Many in the community are uninsured and have multiple medical care needs

A number of universities are located in the Charlotte area

Health care reform

Competition from other health care providers for the medically underserved

Oversupply of physicians means that many will not set up private practices or be able to join just any practice

Managed care

Charlotte market

Threats

Uncertain financial future of health care in general

Health care reform

Loss of patients as they choose HMOs rather than C. W. Williams

Managed care

Reimbursement restructuring

Shortage of health care professionals

“We have had an architect look at the proposed facility. He estimated that it would take about $500,000 for remodeling. According to the tax records, the building and land are worth about $250,000. Since we don't yet know how many patients we will actually receive from Health Care Connection or how many of our patients will choose an HMO, it's hard to decide if we should take the risk.”

What to Do

“At the end of the week I sometimes wonder what I've accomplished,” Michelle stated. “I seem to spend a lot of time putting out fires when I should be concentrating on developing a strategic plan and writing more grants.”

Notes

1. This section is adapted from Mickey Goodson, A Quick History (National Association of Community Health Centers Publication, undated).

2. Utilization and Costs to Medicaid of AFDC Recipients in New York Served and Not Served by Community Health Centers (Columbia, MD: Center for Health Policy Studies, June 1994).

3. Using Medicaid Fee-for-Service Data to Develop Community Health Center Policy (Seattle, WA: Washington Association of Community Health Centers and Group Health Cooperative of Puget Sound, 1994).

4. Key Points: A National Survey of Patient Experiences in Community and Migrant Health Centers (New York: Commonwealth Fund, 1994).

5. Health Insurance of Minorities in the US (Report by the Agency for Health Care Policy and Research, US Department of Health and Human Services, 1992) and Green Book, Overview of Entitlement Programs Under the Jurisdiction of the Ways and Means Committee (US House of Representatives, 1994).

(Swayne 742)

Swayne, Linda E. Strategic Management of Health Care Organizations, 6th Edition. Wiley-Blackwell (STMS), 11/2008. VitalBook file