I need help with this

Integrative and Biopsychosocial Approaches in Contemporary Clinical Psychology

Chapter Objective

To highlight and outline how contemporary clinical psychology integrates the major theoretical models using a biopsychosocial approach.

Chapter Outline

The Call to Integration

Biopsychosocial Integration

Synthesizing Biological, Psychological, and Social Factors in Contemporary Integration

Highlight of a Contemporary Clinical Psychologist: Stephanie Pinder-Amaker, PhD

Application of the Biopsychosocial Perspective to Contemporary Clinical Psychology Problems

Conclusion

Having now reviewed the four major theoretical and historical models in psychology in Chapter 5, this chapter illustrates how integration is achieved in the actual science and practice of clinical psychology. In addition to psychological perspectives per se, a full integration of human functioning demands a synthesis of psychological factors with both biological and social elements. This combination of biological, psychological, and social factors comprises an example of contemporary integration in the form of the biopsychosocial perspective. This chapter describes the evolution of individual psychological perspectives into a more comprehensive biopsychosocial synthesis, perhaps first touched upon 2,500 years ago by the Greeks.

The Call to Integration

While there are over 400 different types of approaches to psychotherapy and other professional services offered by clinical psychologists (Karasu, 1986), the major schools of thought reviewed and illustrated in Chapter 5 have emerged during the past century as the primary perspectives in clinical psychology. As mentioned, these include the psychodynamic, cognitive-behavioral, humanistic, and family systems approaches. Prior to the 1980s, most psychologists tended to adhere to one of these theoretical approaches in their research, psychotherapy, assessment, and consultation. Numerous institutes, centers, and professional journals were (and still are) devoted to the advancement, research, and practice of individual perspectives (e.g., Behavior Therapy and International Journal of Psychoanalysis). Professionals typically affiliate themselves with one perspective and the professional journals and organizations represented by that perspective (e.g., Association for Behavioral and Cognitive Therapies), and have little interaction or experience with the other perspectives or organizations. Opinions are often dogmatic and other perspectives and organizations viewed with skepticism or even disdain. Surprisingly, psychologists with research and science training sometimes choose not to use their objective and critical thinking skills when discussing the merits and limitations of theoretical frameworks different from their own. Choice of theoretical orientation is typically a by-product of graduate and postgraduate training, the personality of the professional, and the general worldview held of human nature. Even geographical regions of the country have been historically associated with theoretical orientations among psychologists and other mental health professionals. For example, the psychoanalytic approach has been especially popular in the northeastern part of the United States, and the behavioral approach has been especially popular in the midwestern and southern parts of the United States.

However, unidimensional approaches have been found to be lacking and of limited use in their approach to the full spectrum of psychological problems. Research has generally failed to demonstrate that one treatment perspective is consistently more effective than another for all patients (Beckham, 1990; Lambert, Shapiro, & Bergin, 1986; Luborsky et al., 2002; Messer & Wampold, 2002; Norcross & Goldfried, 2005; Smith et al., 1980). About 45% of the improvements in psychotherapy, for example, may be attributable to common factors found in all major theories and approaches (Lambert, 1986). Furthermore, some research has suggested that less than 15% of treatment outcome variance can be accounted for by specific techniques (Beutler, Mohr, Grawe, Engle, & MacDonald, 1991; Lambert, 1986; Luborsky et al., 2002). Studies have suggested that a combination of perspectives and techniques may even have powerful synergistic effects (Lazarus, 1989; Messer & Wampold, 2002; Norcross & Goldfried, 2005). Therefore, both research and practice suggest that religious adherence to only one perspective may be counterproductive and naive for most clinical problems.

In reviewing the major theoretical approaches in clinical psychology, it may seem clear that each perspective offers unique contributions toward a better understanding of human behavior and assisting those who seek professional psychological services (Beutler & Groth-Marnat, 2003; Norcross & Goldfried, 2005; O’Brien & Houston, 2000). Adherence to only one school of thought, however, can be rigid and ultimately limiting. In the words of Arnold Lazarus (1995), “Given the complexity of the subject matter, it seems unlikely that any single approach can possess all the answers. So why wear blinders? Why not borrow, purchase, pilfer, import, and otherwise draw upon conceptions and methods from diverse systems so as to harness their combined powers” (p. 399). While no one theory has a lock on the truth or the keys to behavior change, perhaps each has something very important to offer in the greater puzzle of “truth.” Furthermore, debate about which school of thought reigns supreme seems to become moot in the ensuing context of integration (Arnkoff & Glass, 1992; Norcross et al., 2006). As expressed by Sol Garfield and Allen Bergin (1986), “a decisive shift in opinion has quietly occurred ... the new view is that the long-term dominance of the major theories is over and that an eclectic position has taken precedence” (p. 7).

Finally, recent surveys have found that integrative approaches continue to be what most practicing psychologists report doing in their clinical work (Norcross, Karpiak, & Santoro, 2005).

Commonalities among Approaches

With so much emphasis on differences, it is often overlooked that there is some degree of overlap among many of these perspectives. For example, some of the major concepts articulated in one perspective are also expressed in other perspectives, using different terms and language. Those immediate and unfiltered thoughts and feelings that come to mind are referred to as free associations for those from a psychodynamic perspective and automatic thoughts in the cognitive-behavioral lexicon. Both approaches highly value and integrate free association/self-talk into their understanding and treatment of human behavior. Attempts to translate the language of one perspective into another have occurred since 1950, beginning with the work of Dol-lard and Miller. Since research tends to support the notion that one theoretical framework is not superior to another in treating all types of problems, the examination of common denominators among the different theoretical perspectives has attempted to isolate common factors (Goldfried, 1991). This research has suggested that providing the patient with new experiences within and outside of the therapy session is common in all types of psychotherapies (Brady et al., 1980). Goldfried (1991) stated that all psychotherapies encourage the patient to engage in corrective experiences and that they all provide some form of feedback to the patient. Additional similarities discussed by Frank (1982) and others include a professional office associated with healing and being helped; a trained mental health professional who is supportive, thoughtful, professional, and perceived as an expert in human behavior; enhanced hope that thoughts, feelings, and behaviors can change for the better; fees associated with service; and the avoidance of dual relationships (e.g., avoidance of sexual relationships or friendships with patients). James Prochaska (1984, 1995, 2000, 2008) discussed commonalities among theoretical orientations by examining the process of change across different types of problems and different methods of treatment. In his analysis of different orientations to behavior change, he isolated a variety of universal stages, levels, and processes of change. His theory includes five stages of change (i.e., pre-contemplation, contemplation, preparation, action, and maintenance), five levels of change (i.e., symptoms, maladaptive cognition, current interpersonal conflicts, family/systems conflicts, past interpersonal conflicts), and ten change processes (i.e., consciousness raising, catharsis/dramatic relief, self-evaluation, environmental reevaluation, self-liberation, social liberation, counterconditioning, stimulus control, contingency management, and helping relationship). It is beyond the scope of this chapter to outline the specifics of Prochaska’s model; for a more detailed account see Prochaska (1984, 1995, 2000, 2008) and Prochaska and Norcross (2002). Although Prochaska’s perspective has a cognitive-behavioral flavor to it, his theory of change is atheoretical in that it is not based on any one theoretical perspective and can be applied to all perspectives.

Efforts toward Integration

The integration of theoretical and treatment perspectives is challenging and complex. Each perspective has its own language, leaders, and practices. Furthermore, research is challenging to conduct because what happens in a laboratory or research clinic may be very different from what happens in a clinician’s office. For example, a treatment manual that clearly specifies a behavioral intervention for panic disorder used in research is likely not used in clinical practice. Efforts at integration tend to occur in one of three ways: (1) integrating the theories associated with each perspective, (2) developing an understanding of the common factors associated with each perspective, and (3) using eclecticism in a practical way to provide a range of available intervention strategies (Arkowitz, 1989, 1992; Norcross & Goldfried, 2005). Most attempts to integrate perspectives have involved the integration of psychodynamic and behavioral approaches. Perhaps this is due to the fact that during most of the twentieth century, the majority of clinical psychologists have identified themselves (with the exception of eclecticism) as being either psychodynamically or cognitive-behaviorally oriented.

Paul Wachtel (1977, 1982, 1987, 2002, 2008) has been a significant contributor to the evolving framework of integration between the psychodynamic and behavioral points of view. Wachtel was one of the first professionals to integrate psychodynamic and behavioral approaches. For example, Wachtel uses the psychodynamic perspective in focusing on early childhood experiences as well as the notion that unconscious conflicts result in problematic feelings and behaviors. He uses the behavioral principle of reinforcement in the present environment to understand various ongoing emotional, psychological, and behavioral problems. Wachtel further notes that behavioral interventions can improve insight while insight can lead to behavioral change (Wachtel, 1982).

Many authors (e.g., Castonguay, Reid, Halperin, & Goldfried, 2003; Gill, 1984; Messer 2001, 2008; Norcross & Goldfried, 2005; Nuttall, 2002; Ryle, 2005; Stern 2003; Wachtel, 2008) report that psychodynamic and cognitive-behavioral theories have clearly been integrated with much success. Psycho-dynamic therapies have increasingly incorporated cognitive-behavioral theories and practices into their perspectives. For example, many psychodynamic thinkers have become interested in the cognitive influences of mal-adaptive beliefs about self and others in interpersonal relationships (Horowitz, 1988; Messer 2001, 2008; Ryle, 2005; Strupp & Binder, 1984). Furthermore, interest in providing briefer treatments has resulted in the incorporation of cognitive-behavioral problem-solving strategies in dynamic therapy (Strupp & Binder, 1984). Some psychodynamic approaches have also endorsed the behavioral and humanistic principles of focusing on the present or here and now (Weiner, 1975). Contemporary cognitive-behavioral orientations have incorporated the psychodynamic view that attention must be paid to the nature of the therapeutic relationship between the therapist and patient as well as the need for insight to secure behavioral change (Dobson & Block, 1988; Mahoney, 1988; Ryle 2005). Other efforts toward theoretical integration have occurred using family systems theory (D. A. Kirschner & S. Kirschner, 1986; Lebow, 1984), humanistic approaches (Wandersman, Poppen, & Ricks, 1976), and interpersonal theory (Andrews, 1991). For example, the humanistic orientations have endorsed the scientific approach of the cognitive-behavioral orientation (Bugental, 1987) as well as the role of cognition in promoting growth (Bohart, 1982; Ellis, 1980). The behavioral approaches have incorporated family systems theory into their efforts at developing behavioral family therapy (Jacobson, 1985; Jacobson & Margolin, 1979). Using a broader framework, some authors have looked toward an integration of biological, cognitive, affective, behavioral, and interpersonal elements of human behavior (Andrews, 1991; Beckham, 1990; Schwartz, 1984, 1991; Messer 2001, 2008; Norcross & Goldfried, 2005). Rather than looking at the major theoretical perspectives as being mutually exclusive, these authors experience them as all having some corner of the truth, which needs to be examined and pieced together in order to understand behavior and offer useful intervention strategies (Beutler & Groth-Marnat, 2003; Norcross & Goldfried, 2005; O’Brien & Houston, 2000). For example, Stanley Messer’s assimilative integration approach includes psychodynamic, cognitive-behavioral, family systems, and even Yogic/Buddhist approaches (Messer 2001, 2008).

Eclecticism

Professionals maintaining an eclectic or integrative approach to their work tend to use whatever theories and techniques appear to work best for a given patient or problem. Of course, these approaches should be evidence based. Thus, once the psychologist has an adequate understanding of the patient’s problems or symptoms, he or she uses strategies from various perspectives to design a treatment plan best suited to the unique needs of each patient. Lazarus (1971, 2005) argued that professionals can use techniques from various theoretical orientations without necessarily accepting the theory behind them. For example, a psycho-dynamically oriented psychologist might help a patient learn relaxation techniques such as diaphragmatic breathing or muscle relaxation in order to help control feelings of anxiety and panic. The therapy would continue to pursue the underlying basis for these symptoms while affording the patient some immediate relief. A cognitive-behaviorally oriented psychologist might ask a patient who is troubled by insomnia associated with frequent nightmares to describe his or her disturbing dreams and inquire about the patient’s insights into these dreams. A humanistic psychologist might invite a patient to examine irrational beliefs. Irving Weiner stated that, “effective psychotherapy is defined not by its brand name, but by how well it meets the needs of the patient” (Weiner, 1975, p. 44). This has become the “battle cry” of many clinical psychologists. In many ways, someone seeking the professional services of a clinical psychologist is much more interested in obtaining help for his or her particular problem(s) than embracing the particular theoretical orientation of the psychologist. Also, they generally want immediate help with what ails them, not an intellectual discussion or understanding about the philosophy of human behavior. They usually want an approach that is consistent with their personality and their own perspective to problems. However, Eysenck (1970) and others have warned that eclecticism can be a “mish-mash of theories, a hugger-mugger of procedures, a gallimaufry of therapies” (p. 145). Concerns about eclecticism suggest that it can result in a passing familiarity with many approaches but competence in none, as well as muddled and unfocused thinking. Nonetheless, numerous surveys have revealed that eclectic approaches have become more and more common and popular among clinical psychologists (e.g., Norcross, Hedges et al., 2002; Norcross et al., 2005). In fact, integrative approaches have been the most commonly endorsed theoretical approaches by clinical psychologists during the past several decades (Norcross et al., 2005).

An excellent and influential example of an eclectic approach is the multimodal approach of Arnold Lazarus (1971, 1985, 1986, 1996, 2005). In the multimodal approach, treatment reflects the patient’s needs based on seven aspects of behavior. These include behavior, affect, sensation, imagery, cognition, interpersonal relationships, and drugs (referred to as BASIC ID). Interventions include cognitive-behavioral techniques such as imagery, biological interventions such as medication, and humanistic strategies such as empty chair exercises and reflection. Although the work of Lazarus has a cognitive-behavioral slant, many non-cognitive-behavioral techniques and approaches are used in the multimodal approach.

Beyond Psychological Models

As clinical psychology has evolved, more complex theories of human behavior and behavior change have developed utilizing and integrating the major theoretical psychological perspectives in conjunction with biological and social factors. Furthermore, multidimensional and integrative approaches to intervention that reflect a biopsychosocial synthesis have become the trend in contemporary clinical psychology (Lam, 1991; Norcross et al., 2002; Norcross & Goldfried, 2005). Formal education in the biological, psychological, and social influences of behavior have become a requirement for licensure in most states. No longer can a psychologist master only one theoretical perspective while remaining oblivious to other perspectives and hope to obtain a license to practice in his or her state. For example, if a patient requests treatment by a clinical psychologist for tension headaches associated with stress, the psychologist must be able to appreciate the biological, psychological, and social influences on the patient’s symptoms. While not all psychologists can treat all problems, it is incumbent on practitioners to at least know when to make appropriate referrals. The headaches might be associated with stress but they could also be associated with medical problems such as a migraine, brain tumor, or other serious neurological condition. The competent psychologist would request that the patient be evaluated by a physician in order to rule out these other important medical possibilities prior to treating the headaches with biofeedback, relaxation training, psychotherapy, or other psychosocial interventions and strategies in conjunction with any appropriate medical treatment. If a member of a particular religious or ethnic group seeks treatment for an emotional problem, it is important to have adequate awareness and understanding regarding the influences of culture on the behavior or problem in question (American Psychological Association [APA], 2003b; Sue & Sue, 2003, 2008; Sue, 1983, 1988). Ignorance regarding the role of ethnicity, culture, religion, and gender in behavior is no longer tolerated in most professional circles. Examining the biological, psychological, and social influences on behavior has become fundamental in clinical psychology and defines the biopsychosocial framework.

For example, a disabled Latino child, recently immigrating from El Salvador, experiences depression and posttraumatic stress disorder following an experience of sexual abuse perpetrated by a family member. The school teacher notices an increase in sexualized and inattentive behaviors and refers the child to a psychologist who consults with the school. The child tells the psychologist about the sexual abuse and the psychologist, as required by law, must break confidentiality and report the abuse to the state child protection agency. The bilingual psychologist might treat the child and members of the family with a variety of intervention strategies. The range of interventions might include (a) psychodynamic approaches to increase insight and access unconscious anger and resentment, (b) cognitive-behavioral strategies to manage anxiety symptoms and inattentive behavior at school, (c) referral to a psychiatrist for evaluation of the possible use of medication to address the depression, (d) referral to a pediatrician to evaluate potential medical problems associated with the abuse, (e) social and community support and interventions to address cultural issues associated with being an El Salvadoran immigrant as well as legal issues associated with the victimization, (f) family systems approaches to help the entire family cope with the current crisis and avoid future abuse, and (g) humanistic approaches to help support and accept the feelings and behavior of the child and family. This example demonstrates the need to intervene broadly with a wide arsenal of tools given the complexity of issues within the individual and larger family and social systems.

Biopsychosocial Integration

Whereas psychologists have increasingly utilized combined and multimodal psychological models and interventions, contemporary psychology has looked beyond even its own field into biological and sociological realms to enhance its scope and usefulness. The combined effects of biological, psychological, and social factors on behavior have led to the term biopsychosocial, and represents an increasingly appreciated comprehensive approach in clinical psychology. While biological, psychological, and social factors are all viewed as relevant in this perspective, they may not each be equal in their contribution to every problem or disorder. Thus, in the case of a primarily biological disorder such as childhood leukemia, for example, psychological and social factors provide important contributions to the course and treatment of the disease but are not given equal etiological or treatment consideration. Similarly, while a grief reaction following the loss of a loved one may at first glance appear purely psychological, social factors such as family and community support as well as biological factors such as sleeping and eating patterns can complicate or alleviate the severity of symptoms. Thus, an intelligent blending and weighing of these three factors comprise the challenge of biopsy-chosocial integration. Melchert (2007, p. 34) states the need for biopsychosocial integration when he says, “replacing the traditional reliance on an array of theoretical orientations with a science-based biopsychosocial framework would resolve many of the contradictions and conflicts that characterized (earlier) era(s) in (professional psychology).” Having described the major psychological approaches in detail in Chapter 5, the nature of biological and social factors in behavior will be described in this section, leading to clinical examples of biopsychosocial integration in contemporary practice.

Spotlight: Drugs and Obesity

Photo: Courtesy Stockvault.net

Obesity has increased significantly in recent years in the United States and elsewhere. Efforts to help overweight people lose weight are the frequent topic of newsmagazines, television shows, blogs, and scientific research. The biopsychosocial model is needed in the evaluation and treatment of eating disorders such as obesity. Psychological and behavioral interventions that focus on food intake, selection, and the role of emotions such as anxiety, depression, and low self-esteem must be considered as well as social and cultural factors (e.g., access to high-fat foods, ability and motivation to exercise). Furthermore, interventions such as medication can be used effectively in the treatment of eating disorders such as obesity. Although there is no magic pill that will allow people to eat whatever they want and never gain weight, a number of medications have been approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to help treat obesity. For example, Orlistat (also known by the trade names Xenical and Alli), which is a medication that inhibits pancreatic lipase, reduces dietary fat by approximately 30%. Research suggests that those on the medication are more likely to lose weight and regain less weight than control groups after treatment (Aronne, 2001; Bray, 2008; Rivas-Vazquez, Rice, & Kalman, 2003). Side effects include gastrointestinal upset, fecal urgency, oily or soft stool, diarrhea, and flatus with discharge (Bray, 2008; Rivas-Vazquez et al., 2003).

Sibutramine (also known by the trade names Meridia and Reductil) is another approved medication to treat obesity that inhibits the reuptake of several neurotransmitters such as serotonin and norepinephrine. Like Orlistat, those who take Sibutramine tend to be more likely to lose weight and regain less weight than others following treatment (Aronne, 2001; Bray, 2008; Rivas-Vazquez et al., 2003). Side effects include increases in heart rate and blood pressure, upset stomach, and dry mouth.

Research continues to find other biological interventions for obesity. For example, ciliary neurotrophic factor (CNTF) is a promising protein that activates the intracellular signaling pathways in the hypothalamus, which regulates both body weight and food consumption (Bray, 2008; Rivas-Vazquez et al., 2003). Thus, it activates the satiety center in the brain to signal that the person is no longer hungry. Research suggests that it is effective in helping control weight.

These medications, when used in combination with other biopsychosocial interventions, may be useful to the millions of Americans who are obese. However, too often the public gets overly invested and excited about a promising “easy” way to control weight. Numerous medications, fad diets, and gadgets have been sold to the public only to be found to be ineffective or even dangerous. A good example is the excitement regarding the obesity medication, phentermine resin-fenfluramine or “phen-fen,” which was very popular in the early and mid-1990s. The FDA banned the drug in 1997 when it became clear that patients on the medication were at higher risk for heart valve problems. One must proceed cautiously with weight-loss products such as medications, allowing research to adequately determine the effectiveness and safety of the product.

Biological Factors

Since Hippocrates, the close association between biology and behavior has been acknowledged, but not always fully integrated into treatment. Recent advances in medicine and the biological sciences have furthered our awareness of the intimate connection between our physical and psychological selves (Institute of Medicine, 2001; Lambert & Kinsley, 2005). A full understanding of any emotional or behavioral problem must therefore take into consideration potential biological factors.

Some authors have attempted to explain human behavior in terms of biological, genetic, and evolutionary influences (Barkow, 2006; Pinker, 2003; Thase & Denko, 2008). For example, it is well known that there is a strong genetic influence on physical characteristics such as height, weight, hair color, and eye color. Furthermore, it is well known that a variety of physical illnesses such as Huntington’s chorea, phenylketonuria (PKU), Tay-Sachs, Down Syndrome, heart disease, cancer, mental retardation, and psychiatric illnesses such as schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and alcoholism have strong biological or genetic influences (e.g., Dykens & Hodapp, 1997; Gottesman, 1991; Lambert & Kinsley, 2005). This does not mean that a psychiatric condition such as schizophrenia is completely attributable to genetic influences. In fact, an identical twin has about a 50% chance of not developing schizophrenia if his or her twin has the disorder (Gottesman, 1991; Gottesman & Erlenmeyer-Kimling, 2001). Biological and genetic influences have a significant but incomplete contribution to the development and course of many illnesses (Lambert & Kinsley, 2005; Pinker, 2003).

Genetically based chromosomal dysfunction can lead to a number of conditions that involve behavior and learning problems of interest to clinical psychologists. For example, Fragile X, Williams, and Prader-Willi syndromes all involve deletion or dysfunction of chromosomes due to genetic influences, resulting in a variety of cognitive, intellectual, learning, and behavioral problems (Bouras & Holt, 2007; Dykens & Hodapp, 1997; Hodapp & Dykens, 2007). Behavioral and learning problems associated with these disorders have intervention implications that involve both biological and psychosocial strategies.

Even personality traits such as shyness have been shown to have a genetic component (e.g., Kagan, Reznick, & Snidman, 1988; Pinker, 2003; Plomin, 1990; Posner & Rothbart, 2007). Research studying identical twins reared apart from birth have revealed many striking findings that support the notion of a strong biological influence associated with human health, illness, and behavior. Of course, genetic and biological vulnerabilities and predispositions do not necessarily result in the expression of a particular illness or trait. For example, while someone may inherit the vulnerability to develop PKU, environmental factors such as diet determine if the trait is expressed. Therefore, biological predispositions must be examined in the context of the environment (Hodapp & Dykens, 2007; Pinker, 2003; Posner & Rothbart, 2007).

Furthermore, additional biological influences on behavior, such as the role of brain chemicals called neurotransmitters, have demonstrated that brain functioning plays a significant role in human behavior. For example, serotonin (5-hydroxytryptamine or 5-HT) is a neurotransmitter associated with a variety of instinctual behaviors such as eating, sexuality, and moodiness. Low levels of serotonin at the synapse have been associated with impulsive behavior and depression (Institute of Medicine, 2001; Risch, Herrell, Lehner, Liang, Eaves, et al., 2009; Spoont, 1992; Thase, 2009). Another neurotransmitter, dopamine, has been linked to schizophrenia. Therefore, many psychologists and others maintain that biological influences such as inherited characteristics and brain neurochemistry (such as the role of neurotransmitters) greatly influence both normal and abnormal behavior (B. J. Sadock, V. A. Sadock, & Ruiz, 2009; Thase, 2009). The goal of the biological approach is to understand these biological and chemical influences and use interventions such as medication to help those with certain emotional, behavioral, and/or interpersonal problems.

Professionals with strong biological training, such as many psychiatrists, generally favor biological interventions in treating patients. Various types of psychotropic medications such as antipsychotic, antianxiety, and antidepressant medications are frequently used to treat a wide variety of emotional, psychological, and behavioral problems (Barondes, 2005; Glasser, 2003; Risch et al., 2009; Sadock et al., 2009; Sharif, Bradford, Stroup, & Lieberman, 2007). For example, lithium is typically used to treat bipolar disorder (commonly referred to by the general population as manic-depression), while neuroleptics such as Haldol, Thorazine, Risperdal, and Zyprexa are often used to treat psychotic disorders such as schizophrenia. The benzodiazepines such as Valium and Xanax are frequently used to treat anxiety-based disorders such as panic and phobia. Finally, tricyclics such as Elavil, the monoamine oxidase (MAO) inhibitors, and a class of medications called the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), which include Prozac, are used to treat depressive disorders. Newer classes of drugs similar to the SSRIs yet different enough to be considered in their own category, including nefazodone (Serzone) and venlafaxine (Effexor), impact the norepinephrine as well as serotonin neuro-transmitters while Bupropion (Wellbutrin and Zyban) also impacts the dopamine system (Nemeroff & Schatzberg, 2007; Sadock et al., 2009; Stahl, 1998). Tricyclics such as imipramine are also used to treat panic and phobic disorders. Electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) is frequently used to treat severe and resistant depression. The technique involves applying a small amount of electrical current (usually 20 to 30 milliamps) to the patient’s temples for about one minute while the patient is sedated. The treatment results in a seizure or convulsion, which is subsequently associated with a reduction in symptoms in about 60% of the cases (Fink, 2003; Sadock et al., 2009).

These biological interventions are not without side effects. For example, the benzodiazepines can cause drowsiness, tolerance, and both physical and psychological dependence or addiction (American Psychiatric Association, 2000; Baldessarini & Cole, 1988; Hayward, Wardle, & Higgitt, 1989; Spiegal, 1998). Antidepressants such as Prozac can cause insomnia, nervousness, and inhibited orgasms (Sadock et al., 2009). Antipsychotic medication can produce muscle rigidity, weight gain, dry mouth, constipation, a shuffling walk, and an irreversible condition called tardive dyskinesia characterized by involuntary facial and limb movements (Breggin, 1991; Spaulding, Johnson, & Coursey, 2001; Sadock et al., 2009). Tardive dyskinesia can render patients socially impaired if the symptoms cannot be managed by other medications. Although research has failed to find that ECT causes structural damage to the brain (Devanand, Dwork, Hutchinson, Blowig, & Sackheim, 1994; Devanand & Sackheim, 1995; Scott, 1995), relapse rates and memory deficits, usually associated with events occurring around the time of ECT administration, are a common problem (Fink, 2003) and thus this technique remains controversial for these and other reasons (Reisner, 2003). Biological interventions may be used effectively with certain patients but also have important side effects. A perfect pill or “magic bullet” that completely fixes a problem without any side effects or negative factors does not exist.

While medication can greatly help to minimize or eliminate problematic symptoms, additional problems associated with a mental illness may continue to exist. For example, antipsychotic medication or neuroleptics such as Thorazine, Risperdal, or Zyprexa may reduce or eliminate the hallucinations and delusional thinking associated with schizophrenia. Therefore, the patient is bothered no longer by hearing voices or beliefs that have no basis in reality. However, problems with social skills, self-esteem, fears, and comfort with others may not be altered by the use of these powerful medications and must be dealt with using other means (e.g., social skills training, psychotherapy, job skill training).

In addition to medications and other biological treatments such as ECT, technological advances such as the development of computer neuroimaging techniques (CT and PET Scans, and functional MRIs) have improved our understanding of brain–behavior relationships (Mazziotta, 1996; Sadock et al., 2009). Computerized axial tomography (CT) scans were developed in the early 1970s to better view the structures of the brain. CT scans provide computer-enhanced multiple-X-ray-like pictures of the brain from multiple angles. CT scan research has, for example, discovered that schizophrenics have enlarged ventricles or spaces in the brain and experience cortical atrophy over time. Positron emission tomography (PET) scans use radioactive isotopes injected into the bloodstream of a patient to create gamma rays in the body. PET scans not only provide a view of brain structure but also provide information on brain function. Research using PET scan technology has revealed changes in brain blood flow during different intellectual tasks and during different emotional states such as anxiety (Fischbach, 1992). PET scan research has determined that panic is associated with brain cells located in the locus ceruleus in the brainstem, which are also sensitive to the benzodiazepines (Barlow, 2002; Barlow & Craske, 2002; Reiman, Fusselman, Fox, & Raichle, 1989; Sadock et al., 2009). Finally, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) was developed in the early 1980s and provides a detailed visual reconstruction of the brain’s anatomy (Andreasen & Black, 1995; Sadock et al., 2009). The MRI analyzes the nuclear magnetic movements of hydrogen in the water and fat of the body. MRI research has helped to uncover the role of possible frontal lobe damage among schizophrenic patients (Andreasen, 1989) as well as potential tissue loss in bipolar patients (Andreasen & Black, 1995).

Clinical psychologists are unable to prescribe ECT, medication (in most states), or any other biological interventions (e.g., CT or PET scans, MRI). Therefore, psychologists interested in the use of these interventions must work collaboratively with physicians (such as psychiatrists). However, recent efforts have been underway by the U.S. military, the APA, and other organizations to work toward allowing psychologists, with the appropriate training, supervision, and experience, to legally prescribe medications. Psychologists now can prescribe medication in some states (e.g., New Mexico, Louisiana, Guam). This allows psychologists to more fully integrate biological interventions with the psychosocial interventions that they already provide. Prescribing medications by psychologists will be discussed in more detail in Chapter 14.

Some authors also view evolutionary influences as powerful contributors to human behavior (Wilson, 1978, 1983, 1991, 2003; D. S. Wilson & E. O. Wilson, 2007). Although speculative and not based on controlled scientific experimentation, evolutionary explanations for a variety of behaviors and behavioral problems have become popular in recent years. For example, some researchers report that many experiences and difficulties with intimate relationships can be traced to evolutionary influences (Buss, 2003, 2005; Fisher, 1995, 2004). Fisher (1995, 2004) explained that divorces occur often and usually fairly early in a relationship (after about four years) for evolutionary reasons, because about four years were needed to conceive and raise a child to a minimal level of independence. Once a child is about 3 years old, members of a clan could adequately continue with child rearing. Fisher, Buss, and others explain infidelity as evolutionarily helpful because by distributing our genes by mating with a number of partners, we will most likely keep our genes from dying out. Because life was tenuous for our ancestors—death was a realistic daily possibility—having some reproductive options with several people increased the possibility of mating as well as having help taking care of young infants. Maximizing reproductive success and perpetuating the species is enhanced if people mate often and with a variety of partners. Whereas these researchers provide compelling explanations for human intimate relationships from studying the behavior of animals as well as the behavior of our ancient ancestors, people are often very quick to proclaim that human behavior is driven by strong biological forces and, therefore, we cannot help being who we are and behaving as we do. Thus, someone engaged in an extramarital affair who blames the behavior on his or her genetic makeup is likely (and rightfully) to be viewed with skepticism.

Biologically oriented factors emphasize the influence of the brain, neurochemistry, and genetic influences on behavior. They typically lead to biologically oriented approaches to study, assess, and treat a wide range of emotional, psychological, medical, and behavioral problems. Evolutionarily oriented professionals focus on understanding human behavior in the context of our sociobiological roots. The biological and evolutionary perspectives on behavior have become increasingly influential. New discoveries in genetics such as genetic markers for depression, panic, anxiety, obesity, and schizophrenia as well as new discoveries in brain structure and function associated with schizophrenia, homosexuality, and violence have contributed to the ascendancy of the biological perspective. Finally, psychiatry’s emphasis on biological theories of mental illness and medication interventions has also fueled the current focus on biological factors in understanding, diagnosing, and treating mental illness (Fleck, 1995; Glasser, 2003; Kramer, 1993; Michels, 1995; Nemeroff & Schatzberg, 2007; Sadock et al., 2009; Thase, 2009; Valenstein, 2002).

Social Factors

Many clinical psychologists have begun to focus more on both cultural and social influences on behavior. Sociologists, anthropologists, and social workers have been investigating these influences for many years. While most practicing clinical psychologists primarily work with individuals, couples, and families rather than with large organizations or groups, issues such as culture, socioeconomic factors, ethnicity, sexual orientation, religious background, social support, and community resources have received a great deal of attention concerning their important influences on human behavior (APA, 1993b, 2002, 2003; Brown, 1990; Caracci, 2006; Greene, 1993; Jones, 1994; Lopez et al., 1989; National Mental Health Association, 1986; Plante, 2009; Sue & Sue, 2003, 2008; Sue, 1983, 1988; Tharp, 1991; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 1990, 2001).

Professionals maintain that individual behavior is often influenced by the cultural environment as well as by larger social and even political factors. Homelessness, poverty, racism, ethnicity, underemployment, abuse, and even the weather can influence behavior (APA, 1993b, 2003; Caracci, 2006; Cardemil, & Battle, 2003; Economic Report of the President, 1998; Lewis, 1969; Lex, 1985; Roysircar, Sandhu, & Bibbins, 2003; Tharp, 1991). Thus, individual human behavior cannot be viewed apart from the larger social context. For example, compelling research has demonstrated that developing schizophrenia is 38% more likely for those living in urban environments relative to rural environments (Caracci, 2006; Lewis, David, Andreasson, & Allsbeck, 1992; van Os, Hanssen, Bijl, & Vollebergh, 2001). While no one would suggest that city living alone would cause someone to become schizophrenic, perhaps vulnerable persons who are at risk for the development of schizophrenia are more likely to develop symptoms in an urban rather than a suburban or rural environment. Depression and drug abuse are also more prevalent in urban environments while alcoholism is more common in rural places (Caracci, 2006; Eaton et al., 1984; Regier et al., 1984). Although disorders such as schizophrenia, depression, and substance abuse can be found in all cultures and countries, social factors such as culture, social expectations, racism, and economic factors often determine how symptoms are presented. For example, while auditory hallucinations are most common in developed countries such as the United States, visual hallucinations are most common in less-developed countries such as those in many parts of Africa and Central America (Ndetei & Singh, 1983).

Case Study: Mary—Integrating Biological Factors

Given the significant research into biological aspects of panic disorder, several key insights are germane to Mary’s case. First, panic and other anxiety disorders have a strong familial contribution, in that individuals whose family members have these disorders are at increased risk of also developing the disorders. Second, neurotransmitters associated with the GABA-benzodiazepine and serotonergic systems have been implicated in the development of panic disorder (American Psychiatric Association, 2000; Bell & Nutt, 1998; Charney et al., 2000; Deakin & Graeff, 1991; Gray, 1982, 1991; Roy-Byrne & Crowley, 2007; Sadock et al., 2009). Therefore, medications prescribed by a physician such as benzodiazepines (e.g., Valium and Xanax) and antidepressants (e.g., Zoloft and Lexapro) may be helpful in altering the biological neurochemistry associated with Mary’s panic symptoms (e.g., Asnis et al., 2001; Roy-Byrne & Crowley, 2007). However, potential side effects including addiction potential would need to be fully discussed and Mary clearly informed as to her biological and other treatment options.

Social relationships appear influential in protecting individuals from a variety of physical and psychological problems, including depression, hypertension, and alcoholism (Brown, Nesse, Vinokur, & Smith, 2003; Ellison & Gray, 2009; House, Landis, & Umberson, 1988). In fact, research studies in several countries have found that a large network of social contacts increases the chance of living a long life (Brown et al., 2003; Berkman & Syme, 1979; Ellison & Gray, 2009; House, Robbins, & Metzner, 1982). The relationship between social support and longevity exists even after accounting for other important risk factors such as hypertension, smoking, and alcoholism. Social support also helps people cope more effectively and recover more quickly from both physical and psychological problems (Ellison & Gray, 2009; Mahoney & Restak, 1998; McLeod, Kessler, & Landis, 1992; T. Seeman, 2001).

Social factors can be damaging as well. Social influences can be so powerful that they can even lead to death. For example, disease and death frequently closely follow separation from a spouse through death or divorce. This relationship is especially common among elderly men (Arling, 1976; Bowling, 2009).

Spotlight: Poverty and Mental Health

Photo: Courtesy Zach Plante.

Tragically, 37 million Americans live below the poverty line with about 13% of all Americans living in poverty (U.S. Census Bureau, 2008). Twenty-five percent of African American and Latina women live below the poverty line and a third of women who head households live in poverty. The United States has the highest poverty rate among wealthy nations (Belle & Doucet, 2003). The richest 1% of the population in America owns more wealth than the bottom 95% (Wolff, 1998) with an average CEO earning 475 times as much as his employees (Giecek, 2000).

What does poverty have to do with mental health? Most researchers and clinicians say plenty (Wan, 2008). For example, depression is very common among the poor and most especially among poor women and children (Eamon & Zuehl, 2001; Wan, 2008). Those who are poor rarely get mental health or health-care services (Coiro, 2001; Conger & Donnellan, 2007; Wan, 2008). Sadly, 83% of low-income mothers have been physically or sexually abused and usually both while one-third experience posttraumatic stress disorder (Belle & Doucet, 2003). According to the Institute of Medicine (2001), the poor are more likely to be exposed to health-damaging toxins, have fewer social support systems and networks, and are much more likely to face discrimination.

Therefore, fighting poverty likely increases the chances for better mental and physical health among the poor (Conger & Donnellan, 2007; Nelson, Lord, & Ochocka, 2001; Wan, 2008). Clinical psychologists who work with the poor are well aware of the challenges facing these populations. Community resources have steadily decreased in recent years to help the poor in the United States, Canada, the United Kingdom, and elsewhere (Conger & Donnellan, 2007; Nelson et al., 2001; Wan, 2008).

Professionals with a great deal of training and experience in the social influences on behavior, such as social workers, generally favor social interventions in helping patients. Interventions such as improved housing and employment opportunities, community interventions such as Project Head-Start, providing low-cost and high-quality preschool experiences for low-income and high-risk families, and legal strategies such as laws to protect battered women and abused children are often the focus of many of these professionals.

The powerful influences of cultural and ethnic background as well as social issues such as poverty, homelessness, racism, violence, and crime have been associated with psychological functioning and human behavior, lending support to the importance of more global social and systems thinking (APA, 1993b, 2003; Bowling, 2009; Cardemil & Battle, 2003; Ellison & Gray, 2009; Lopez et al., 1989; Schwartz, 1982, 1984, 1991; Sue & Sue, 2003, 2008; Tharp, 1991). No contemporary clinical psychologist can overlook social context when seeking to understand and treat psychological problems. The APA provides guidelines to psychologists that include that they “recognize ethnicity and culture as significant parameters in understanding psychological processes” (APA, 1993b, p. 46; see APA, 2003a). These issues are further discussed in Chapter 14.

Synthesizing Biological, Psychological, and Social Factors in Contemporary Integration

Several theories have influenced the development of this integrative and contemporary biopsychosocial perspective and a brief review of them is warranted. This group includes the diathesis-stress perspective, the reciprocal-gene-environment perspective, and the psychosocial influence on biology perspective.

The Diathesis-Stress Perspective

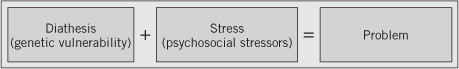

The diathesis-stress perspective is a causal perspective for illness or problems. It suggests that a biological or other type of vulnerability in combination with psychosocial or environmental stress (e.g., divorce, financial troubles, unemployment) creates the necessary conditions for illness to occur (Bremner, 2002; Eisenberg, 1968; Meehl, 1962; Segal & Ingram, 1994; Taylor & Stanton, 2007; Zubin & Spring, 1977). The diathesis-stress perspective states that people have a biological, genetic, cognitive, or other tendency toward certain behaviors and problems. A susceptibility emerges such that certain individuals are more prone to developing potential traits, tendencies, or problems. For example, if someone has one biological parent with hypertension (i.e., high blood pressure), she has a 45% chance of developing high blood pressure herself even if she maintains normal weight, minimizes her fat and salt intake, and obtains adequate physical exercise. If both biological parents have hypertension, the odds soar to 90% (S. Taylor, 2009). Another example includes schizophrenia, since in fact much of the research supporting the diathesis-stress perspective focuses on this serious mental illness (Eisenberg, 1968; Walker & Tessner, 2008 Zubin & Spring, 1977). Schizophrenia occurs in about 1% of the population. However, if a person has an identical twin with schizophrenia, there is a 48% chance of developing the disorder. If a person has a fraternal twin with schizophrenia, there is a 17% chance of developing the disorder (Gottesman, 1991; Gottesman & Erlenmeyer-Kimler, 2001; Walker & Tessner, 2008). Therefore, diathesis means that someone is susceptible to developing a particular problem due to some inherent vulnerability. When certain stressors emerge or the conditions are right, the problem then becomes manifest.

A disorder will occur when the biological or other vulnerability and environmental stressors interact in a sufficient manner to unleash the problem (Figure 6.1). For example, people with significant family histories of schizophrenia may experience their first psychotic episode during the stress of moving to a new city or starting college. Or individuals with a family history of alcoholism might develop the problem during college when many opportunities to drink are available and reinforced by peers. For example, Mary (the case example) may have a biological predisposition to panic and anxiety disorders due to her genetic and biological makeup. The stress of her father’s death and her failure to develop necessary levels of self-confidence may have resulted in this predisposition becoming expressed in the form of a panic disorder.

Figure 6.1 The diathesis-stress model.

Spotlight: Genetics and Psychology

New and exciting research in genetics highlighted by the international efforts of the human genome project and the successful cloning of several animals has resulted in an explosion of information about genetics that has enormous implications for understanding disease and behavior (International Human Genome Sequencing Consortium, 2001; Kaiser, 2008; Miller & Martin, 2008). The resulting research will undoubtedly alter our methods of predicting, understanding, preventing, and treating a host of gene-related problems such as cancer, heart disease, Alzheimer’s disease, learning disabilities, and numerous other problems (Miller & Martin, 2008). As scientists have been able to fully map the human genome and use genetic information to clone animals, many questions and issues emerge that clinical psychologists can be very helpful with managing. For example, if genetic testing results in the knowledge that a patient has a high risk of passing on a potentially fatal genetically based illness (e.g., breast cancer, colorectal cancer, cystic fibrosis) to their potential offspring, they may wonder if they should have children. If genetic testing suggests that a young woman is very likely to develop a potentially fatal disease such as breast cancer, should she consider having a prophylactic mastectomy? If prenatal genetic testing suggests that your child is highly likely to suffer from a genetically based illness that is troublesome but not life threatening (e.g., Tourette’s syndrome, Asperger’s syndrome), should you consider an abortion? If a couple is biologically unable to have children, should they consider cloning if the technology and service is available to them? Should stem cells be harvested from a fetus in order to use the cells to treat another person with a potentially fatal disease? How do you manage the stress of knowing from genetic testing that you will definitely develop a fatal disease in the foreseeable future? The science associated with genetics is highly relevant to clinical psychologists who may conduct research on genetically based illnesses or who clinically treat patients who either suffer from these illnesses or must make important life decisions based on their risk profiles.

The Reciprocal-Gene-Environment Perspective

Some argue that genetic influences might actually increase the likelihood that an individual will experience certain life events (Rende & Plomin, 1992). Thus, certain individuals may have the genetic tendency to experience or seek out certain stressful situations. For example, someone with a genetic tendency toward alcoholism may develop a drinking problem that results in work, relationship, and financial strains. These stressors may result in further drinking, thus worsening both the alcohol problem and life stressors. Someone with a genetic predisposition toward attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) is likely to be impulsive. This impulsivity might result in making poor decisions concerning potential marital partners, leading to divorce and other relationship problems. Stressful relationships and divorce may then exacerbate their attention problems. The reciprocal-gene-environment perspective suggests that there is a close relationship between biological or genetic vulnerability and life events such that each continuously influences the other. Some research suggests that the reciprocal-gene-environment perspective may also help to explain depression (Kalat, 2008; McGuffin, Katz, & Bebbington, 1988) and even divorce (McGue & Lykken, 1992).

Case Study: Mary—Integrating Social Factors

A number of social factors further contribute to an understanding of Mary. First, Mary’s Irish Catholic upbringing was marked by repression of feelings and a tendency to experience intense guilt. Her current social environment is exceedingly narrow, limited by her agoraphobia and avoidance of new situations. It may therefore be useful to first engage her priest and church community in working through deeply held religious beliefs that contribute to her sense of guilt and emotional restriction as well as toward broadening her contact with others. Connection to social support through her church community could lead to some volunteer responsibilities and eventually greater contact and involvement in the larger community. Thus, sociocultural and religious factors contribute largely to Mary’s experience and can be used in a positive manner to assist her.

Psychosocial Influences on Biology

In addition to the notion that biology influences psychosocial issues, an alternative theory suggests that psychosocial factors actually alter biology (e.g., Bremner, 2002; Chida & Steptoe, 2009; Kalat, 2008). For example, research has found that monkeys reared with a high degree of control over their choice of food and activities were not anxious but were aggressive when injected with an anxiety-inducing medication (i.e., a benzodiazepine inverse agonist) that generally causes anxiety compared with a group of monkeys raised with no control over their food and activity choices (Insel, Champoux, Scanlan, & Soumi, 1986). Early rearing experiences greatly influenced how monkeys responded to the effects of medication influencing neurotransmitter activity. Other research has demonstrated that psychosocial influences can alter neurotransmitter and hormonal circuits (Anisman, 1984; Institute of Medicine, 2001; Kalat, 2008). Animals raised with a great deal of exercise and stimulation have been found to have more neural connections in various parts of the brain than animals without an active background (Greenough, Withers, & Wallace, 1990). Social status has also impacted hormone production such as cortisol, which impacts stress (Institute of Medicine, 2001; Kalat, 2008). Other psychosocial factors appear to impact biological functioning as well. For example, social isolation, interpersonal and environmental stress, pessimism, depression, and anger have all been found to be closely associated with the development of various illnesses and even death (Bremner, 2002; Chida & Steptoe, 2009; Kalat, 2008). These illnesses include cardiovascular disease such as hypertension and heart attacks as well as cancer (see Chida & Steptoe, 2009; Goleman, 1995; Kalat, 2008; Kiecolt-Glaser, McGuire, Robles, & Glaser, 2002; and Shorter, 1994 for reviews). Hostility, for example, has been found to be an independent risk factor for coronary heart disease. It is believed that the heightened physiological arousal associated with chronic feelings of anger may promote problematic atherogenic changes in the cardiovascular system (Chida & Steptoe, 2009; Miller, Smith, Turner, Guijarro, & Hallet, 1996).

Development of the Biopsychosocial Perspective

In 1977, George Engel published a paper in the journal Science championing the biopsy-chosocial perspective in understanding and treating physical and mental illness. This perspective suggests that all physical and psychological illnesses and problems have biological, psychological, and social elements that require attention in any effective intervention. The biopsychosocial perspective further suggests that the biological, psychological, and social aspects of health and illness influence each other. The biopsychosocial perspective has been accepted in both medicine and psychology with research support demonstrating its validity (Carmody & Matarazzo, 1991; Fava & Sonino, 2008; Johnson, 2003; Miller, 1987). The biopsychosocial perspective became the foundation for the field of health psychology in the early 1980s (Schwartz, 1982), and has quickly become an influential perspective in clinical psychology and other fields (Fava & Sonino, 2008; Johnson, 2003; Lam, 1991; Levy, 1984; McDaniel, 1995; Melchert, 2007; Sweet et al., 1991; Taylor, 2009). In fact, Melchert (2007, p. 37) states that “it has been incorporated into the curricula in nearly all medical schools in the United States and Europe ... and officially endorsed by the APA ... and 22 other health care and social service organizations.” Melchert further states that “Although other comprehensive, integrative perspectives on human development and functioning have been developed, none enjoys the widespread recognition and acceptance the (biopsychosocial) approach does” (p. 37). It is important to mention that the biopsy-chosocial approach is not another term for the medical model. Nor is it another term for a biological approach to psychology and clinical problems.

The biopsychosocial approach is contextual and states that the interaction of biological, psychological, and social influences on behavior should be addressed in order to improve the complex lives and functioning of people who seek professional health and mental health services (Engel, 1977, 1980; Lam, 1991; McDaniel, 1995; Schwartz, 1982, 1984). The biopsychosocial framework applies a systems theory perspective to emotional, psychological, physical, and behavioral functioning (Lam, 1991; Levy, 1984; McDaniel, 1995; Schwartz, 1982, 1984). The “approach assumes that all human problems are biopsychosocial systems problems; each biological problem has psychosocial consequences, and each psychosocial problem has biological correlates” (McDaniel, 1995, p. 117). Miller (1978), for example, discussed seven levels of systems, each interdependent on the other. These include functioning at the cellular, organ, organism, group, organization, society, and supernatural levels. Furthermore, Miller outlined 19 additional sublevels present at each of the major 7 levels of functioning. Dysfunction at any level of functioning leads to dysregulation, which in turn results in dysfunction at other levels. Thus, changes in one area of functioning (such as the biological area) will likely impact functioning in other areas (e.g., psychological area). Chemical imbalances might occur at the cellular level in the brain, which leads to mood dysfunction in the form of depression. The depressive feelings may then lead to interpersonal difficulties that further impact job performance and self-esteem. Stress associated with these problems at work and home may then lead to further brain chemical imbalances and further depression. Similarly, in an adolescent, Japanese-American female with anorexia nervosa, the intimate interactions between (a) psychological needs for control and mastery, (b) cultural expectations of thinness in women and achievement in Japanese-American culture, combined with (c) pubertal hormonal changes, all conspire to create a dysregulated system with biological, psychological, and social factors each compounding and contributing to the dysfunction the others. Thus, the systems perspective of the biopsychosocial perspective highlights the mutual interdependence of all systems. The biopsychosocial perspective is holistic in that it considers the whole person and specifically the holistic interaction of biological, psychological, and social influences (Fava & Sonino, 2008).

Highlight of a Contemporary Clinical Psychologist

Stephanie Pinder-Amaker, PhD

Photo: Courtesy Stephanie Pinder-Amaker

Birth Date: June 19, 1960

College: Duke University, BS, May 1982

Graduate Program: Vanderbilt University, PhD, 1988

Clinical Internship: Yale University School of Medicine, New Haven, CT, July 1986–June 1987

Current Job(s): Director, College Mental Health Initiative, McLean Hospital and Instructor in Psychology, Harvard Medical School

Pros and Cons of Being a Clinical Psychologist:

Pros: “So many exciting career opportunities are available throughout academic, clinical, research and administrative realms.”

Cons: “The compassion that we have as clinicians can sometimes interfere with the judgment needed to become a good administrator. There are excellent training courses that can assist with developing the latter.”

Influence of Theoretical Models in Your Work: “I had the experience of attending Vanderbilt at a time when they encouraged graduate students to take courses in two theoretically and organizationally distinct programs. One was cognitive-behaviorally oriented and the other was psychodynamic. I learned both theoretical models from faculty who were very passionate and committed to their respective approaches. In the end, I was able to appreciate and integrate the best of both worlds and discovered that both approaches have a great deal more in common than I had expected. Both schools influenced my clinical work and made me a more flexible practitioner.”

Future of Clinical Psychology: “Our training lends itself to being able to address many contemporary challenges. For example, higher education administration is leaning heavily upon clinical psychology to address the college mental health crisis. The economic crisis has all industries looking to us for guidance in navigating these difficult times. As the field continues to grow and technology expands the ‘classroom,’ we should remember the basics—that we also have the training and expertise to become outstanding educators. Because undergraduate students are naturally drawn to psychology, we have the unique opportunity to engage students in creative ways. An ‘Intro to Psychology’ course (where most students first encounter the field) can be so inspiring if we embrace the challenge of highlighting for students the significant impact they can have in the profession and the relevance that clinical psychology will always have for their lives.”

| Typical Schedule: | |

| 9:00 | Review schedule and daily list of college students who have been admitted to the hospital; follow up accordingly. |

| 10:00 | Chair CMHI Student Advisory Committee. |

| 11:00 | Meet with postdoctoral fellow or program assistant for ongoing supervision. |

| 12:00 | Lunch (often with hospital staff or students). |

| 1:00 | Explore funding opportunities (e.g., grants, development) for program development. |

| 2:00 | Chair College Mental Health Initiative Work Group meeting. |

| 3:00 | Meet with regional counseling center directors or visit a local campus. |

| 4:00 | Manage e-mails, make phone calls, draft/edit proposals for new projects. |

| 5:00 | Review college database and follow up re: incomplete/missing entries. |

Application of the Biopsychosocial Perspective to Contemporary Clinical Psychology Problems

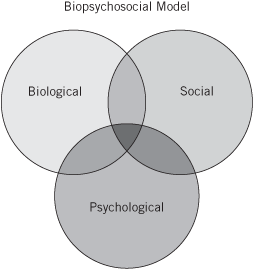

The biopsychosocial perspective is generally viewed as a useful contemporary approach to clinical psychology problems (Figure 6.2; Fava & Sonino, 2008 Johnson, 2003; Lam, 1991; McDaniel, 1995; Taylor, 2009). We next illustrate how this multidimensional, systemic, and holistic approach is employed with the complex problems faced by clinical psychology and related disciplines.

Figure 6.2 The integrative biopsychosocial perspective.

Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder

Obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) is an anxiety disorder involving obsessions (recurrent and persistent thoughts, images, impulses) and compulsions (repetitive behaviors such as hand washing, checking, ordering, or acts) (American Psychiatric Association, 2000). Frequent obsessions might include wishing to hurt oneself or others, or fear of contamination through contact with germs or others. Compulsions might include repeatedly checking to ensure that the stove is turned off or that the door is locked, constantly washing hands to avoid germs and contamination, or performing bizarre rituals. OCD occurs among approximately 3% of the population (American Psychiatric Association, 2000). However, milder forms of obsessions and compulsions that are not severe enough to be considered a disorder commonly occur among many people. OCD tends to be more common among males than females and symptoms generally first appear during adolescence or early adulthood (American Psychiatric Association, 2000).

Brain imaging techniques have found that OCD patients have hyperactivity in the orbital surface of the frontal lobe, the cingu-late gyrus, and the caudate nucleus (Breiter, Rauch, Kwong, & Baker, 1996; Damsa, Kosel, & Moussally, 2009; Insel, 1992; Micallef & Blin, 2001). Furthermore, the neurotransmitter, serotonin, appears to be particularly active in these areas of the brain. OCD patients are believed to have less serotonin available than non-OCD controls (Kalat, 2008; Lambert & Kinsley, 2005). It is, however, unclear what causes these brain differences. Does the biology impact the behavior or does the behavior impact the biology? In other words, does the activity of neurotransmitters in certain sections of the brain cause people to develop OCD symptoms or do the symptoms themselves alter brain chemistry? Research evidence suggests that there may be an interaction (Baxter et al., 1992; Damsa et al., 2009; Insel, 1992; Kalat, 2008; Lambert & Kinsley, 2005). For example, a person can develop OCD following surgery to remove a brain tumor in the orbital frontal area of the brain (Insel, 1992). Thus, a specific trauma to the brain can result in OCD in individuals never troubled by obsessions or compulsions. Evidence has also shown that psychological interventions such as the cognitive-behavioral techniques of exposure and response prevention can alter brain circuitry (Baxter et al., 1992). Thus, an interaction between biological and psychological influences is likely to create or reduce OCD behavior. Additionally, social influences such as culture, religious faith, and social support influence the nature, course, and prognosis of OCD (Greist, 1990; Insel, 1984, 1992; Micallef & Blin, 2001; Plante, 2009; Riggs & Foa, 1993). Current treatments may involve a biopsychosocial approach that includes a drug such as Prozac that inhibits the reuptake of serotonin; neurosurgery (in extreme cases); cognitive-behavioral psychotherapy using exposure and response prevention techniques; social support and education through psychoeducational groups; and psychotherapy, which may include marital and/or family counseling as well as supportive and insight-oriented approaches (Foa & Franklin, 2001; Franklin & Foa, 2008; Koran, Thienemann, & Davenport, 1996).

01; Franklin & Foa, 2008; Koran, Thienemann, & Davenport, 1996).

Panic Disorder and Anxiety

Anxiety-related panic disorder provides another useful application of the biopsychosocial perspective. While everyone has experienced anxiety at various times in their lives, some experience full-blown panic attacks. Panic attacks are characterized by an intense fear that arises quickly and contributes to a variety of symptoms including heart palpitations, sweating, chest pain, shortness of breath, dizziness, and depersonalization (American Psychiatric Association, 2000). While intense fear can be an adaptive mobilizing response in the face of real danger (e.g., preventing a car accident or running away from an assailant), people with panic attacks have a maladaptive response to an imagined threat that often prevents them from engaging in a variety of activities most people take for granted, such as grocery shopping, traveling over bridges, or leaving their home to run errands in a car. About 4% of the population experience panic disorder with onset typically occurring during adolescence or early adulthood (American Psychiatric Association, 2000). Although panic disorder is found throughout the world, symptoms manifest differently depending on the cultural context.

Biopsychosocial factors influence the development, maintenance, and prognosis of panic behavior (Barlow & Craske, 2000; Fava & Morton, 2009; Graeff & Del-Ben, 2008; Roth, 1996). First, evidence suggests that a combination of genetic factors make some people vulnerable to experiencing anxiety or panic attacks (Barlow, 2002; Charney et al., 2000; Fava & Morton, 2009; Graeff & Del-Ben, 2008). Furthermore, neurotransmitter activity, specifically the influence of gamma amino butyric acid (GABA), serotonin, and norepinephrine, have been associated with people who experience panic (Charney et al., 2000; Deakin & Graeff, 1991; Fava & Morton, 2009; Graeff & Del-Ben, 2008; Gray, 1991). Neurotransmitter activity in the brain stem and midbrain have been implicated (Fava & Morton, 2009; Graeff & Del-Ben, 2008; Gray, 1991). Second, psychological contributions to the development of panic involve learning through modeling (Bandura, 1986) as well as emotionally feeling out of control of many important aspects of one’s life (Barlow, 2002; Barlow & Craske, 2000; Li & Zinbarg, 2007). Cognitive explanations and situational cues also appear to contribute to panic (Clark, 1988; Roth, 1996; Teachman, Woody, & Magee, 2006). For example, heart rate increases due to exercise or excitement may result in fear that panic is imminent. Panic sufferers are thus more vigilant regarding their bodily sensations. This awareness fuels further panic, resulting in a cycle of anxiety. Panic thus becomes a learned alarm (Barlow, 2002; Barlow & Craske, 2000; Landon & Barlow, 2004; Teachman et al., 2006). Finally, social factors such as family and work experiences, relationship conflicts, and cultural expectations may all contribute to the development and resolution of panic. Biological vulnerability coupled with psychological and social factors create the conditions for fear and panic to occur.

Spotlight: Empirically Supported Treatment of Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder among Children

Approximately 1 in every 200 children under the age of 18 experiences obsessive-compulsive disorder that is severe enough to significantly disrupt school and social functioning (March & Mulle, 1998). Sadly, OCD in children is frequently not diagnosed. Treatment reflects biopsychosocial principles using a combination of medication (such as Prozac, Zoloft, or Anafranil when needed and when symptoms are especially difficult to manage and treat) and cognitive-behavioral psychotherapy that offers exposure and response prevention strategies.

John March and Karen Mulle offer an empirically supported treatment protocol for OCD in children (March, 2006; March & Mulle, 1998). It includes a manual for up to 21 sessions. Treatment begins with psychoeducational information presented to the parents and impacted child. Session 2 focuses on presenting the notion of an OCD toolkit of a variety of cognitive-behavioral techniques that can be used to fight off and cope with OCD. One technique includes “talking back” to OCD in an effort to not let OCD “boss you around.” “OCD mapping” includes efforts to self-monitor or make regular assessments of OCD symptoms and triggers as well as the impact they have on the child’s daily experience at home, school, and elsewhere. Subsequent sessions highlight the need to practice exposure and response prevention strategies to deal with OCD problems both small and large moving up a stimulus hierarchy. Family sessions are scheduled periodically as well during the course of treatment. Later sessions focus on relapse prevention strategies as well as periodic booster sessions. The treatment manual is informative for parents and clinicians alike and includes a variety of exercises, assessment tools, references, and practical tips. Treatment also takes into consideration co-morbid diagnoses, potential cultural issues, and other factors that make treatment appropriate for any given child and family. The March and Mulle approach to OCD in children represents one of many new emerging evidence-based treatment approaches specifically designed for children and adolescents (Barrett, Farrell, Pina, Peris, & Piacentini, 2008; Kazdin & Weisz, 2003).

Case Study: Hector Experiences Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder (Biopsychosocial)

Hector is an 18-year-old first-generation Mexican American living with his immigrant parents, two sisters, and maternal grandmother. Hector has recently completed high school, and has deferred his acceptance to a university due to the severity of his current symptoms. Hector’s first language is Spanish, and he is also fluent in English.

Presenting Problem: Hector suffers from an obsessive-compulsive disorder that first emerged at age 14. His symptoms involve fears of contamination through contact with germs, blood, or other people. His fears compel him to wash his hands excessively throughout the day, disinfect his room at home, repeatedly cleanse any foods he consumes, wear gloves in public, and refuse to use public restrooms or restaurants. Hector’s symptoms have greatly interfered with his social life, and he is largely isolated from peers or others outside of his immediate family. He is underweight due to his fear of many food items’ safety and because of the extensive rituals he performs to cleanse anything he consumes. He also expresses some depressive symptoms in light of his feeling a prisoner to his obsessions and compulsions and due to their negative impact on his social and career goals.

Biological Factors: Hector’s family history is positive for several paternal relatives having symptoms suggestive of obsessive-compulsive disorder, and research strongly supports a prominent biological/genetic role in the etiology of this disorder. Therefore, abnormalities in neurochemistry may be contributing greatly to his debilitating obsessions and compulsions.

Psychological Factors: Hector has always had a cautious personality, marked by a desire for order and predictability and a perfectionistic style. His ability to achieve success through highly ordered, careful, and perfectionistic behavior has ultimately served to reduce anxiety and enhance his self-esteem and family’s pride in him. His high need for control extends into his grooming, exercising, eating, socializing, and academics.

Social Factors: Hector’s family-centered upbringing has nurtured his increasing desire to stay within his home, to perform well, to aspire toward educational achievement and career success, and to feel a deep attachment to his family and Mexican heritage. Due to his parents’ experience as primarily Spanish-speaking immigrants, he shares their suspicion of mental health professionals and other services that are perceived as having “official” or government ties.

Biopsychosocial Formulation and Plan: Hector’s significant family history of obsessive-compulsive behavior speaks to a strong biological/genetic vulnerability to obsessive-compulsive disorder. While viewed by many as primarily a biological disorder, both psychological and social factors and interventions are essential to any successful treatment with Hector. Both his personality style and stressful school environment and social context that encourages achievement, home life, and suspicion of mental health professionals may subtly impact the course and treatment of Hector’s obsessive-compulsive symptoms.