250 words DQ

CHAPTER 4: Power and Culture: An Anthropologist’s View

Learning Objectives

After reading this chapter, students will be able to:

Understand how anthropologists view power.

Explain the role values and beliefs play in ensuring cultural stability.

Understand how power relationships begin and evolve.

Describe how the American family has changed, and explain how these changes affected the power distribution within society.

The Origins of Power

Power is exercised in all societies. Every society has a system of sanctions, whether formal or informal, designed to control the behavior of its members. Informal sanctions may include expressions of disapproval, ridicule, or fear of supernatural punishments. Formal sanctions involve recognized ways of censuring behavior—for example, ostracism or exile from the group, loss of freedom, physical punishment, mutilation or death, or retribution visited upon the offender by a member of the family or group that has been wronged.

Power in society is exercised for four broad purposes:

To maintain peace, order, and stability within the society

To organize and direct community enterprises

To conduct warfare, both defensive and aggressive, against other societies

To rule and exploit subject peoples

functions of power in society

maintain internal peace, organize and direct community enterprises, conduct warfare, rule and exploit

Even in the least-developed societies, power relationships emerge for the purposes of maintaining order, organizing economic enterprise, conducting offensive and defensive warfare, and ruling over subject peoples.

At the base of power relationships in society is the family or kinship group. A family is traditionally defined as a residential kin group. Typically, a family consists of an adult female and an adult male, sometimes joined through marriage, as well as dependent children. Though this is typical, there are numerous variations including families with only one adult or families not related by blood. But within most families, power is exercised in some fashion. Typically this occurs when work is divided between male and female and parents and children and when patterns of dominance and submission are established between male and female, parents and children.

family

traditionally defined as a residential kin group

In the simplest societies, power relationships are found partially or wholly within family and kinship groups. True political (power) organizations begin with the development of power relationships among and between family and kinship groups. As long as kinship groups, or people related to one another by blood, are relatively self-sufficient economically and require no aid in defending themselves against hostile outsiders, political organization has little reason to develop. But the habitual association of human beings in communities or local groups generally leads to the introduction of some form of a more formal political organization where power is exercised.

kinship group

people related to one another by blood

The basic power structures are voluntary alliances of families and clans who acknowledge the same leaders. They also habitually work together in economic enterprises. In order to maintain peaceful relations, they agree to certain standards of conduct. They also cooperate in the conduct of offensive and defensive warfare. Thus, power structures begin with the development of cooperation among families and kinship groups. This cooperation creates relationships that can be mutually advantageous both economically and in terms of safety.

In some societies, arranged marriages are the norm. Here, a bride and groom exchange vows in a traditional marriage ceremony in India.

Warfare frequently leads to another purpose for power structures: ruling and exploiting peoples who have been conquered in war. Frequently, traditional societies that have been successful in war learn that they can do more than simply kill or drive off enemy groups. Well-organized and militarily successful tribes learn to subjugate other peoples, retaining them as subjects, for purposes of political and economic exploitation. The power structure of the conquering group takes on another function—that of maintaining control over and exploiting conquered peoples.1

Anthropology’s Examination of Power

Within the social sciences, anthropology examines humans, their societies, and the power structures described above through a broad perspective. Anthropology succeeds in integrating many disciplines of study, including some of the humanities, social sciences (including psychology, political science, and economics), as well as knowledge garnered through biology, geology, and other physical sciences. Many anthropologists focus their energies on describing humans, societies, and power structures at various points in time and in various places; others are concerned with using knowledge derived from anthropological studies to improve human existence. Within the discipline of anthropology are four subfields. These include archaeology, biological and physical anthropology, linguistic anthropology, and socio-cultural anthropology.

Archaeology

Archaeology—the study of human cultures through their physical and material remains—relies on the examination of relics—the remnants of human experience—to analyze the behaviors of past cultures. For example, through the analysis of something as simple as pottery remains, anthropologists might learn a great deal about a society—the size of water jugs might indicate their access to potable water, utensils might shed light on the common foods that were consumed, decorations might demonstrate trade patterns with other societies, art depicted on the pottery might reflect common stories of the society.

archaeology

the study of human cultures through their physical and material remains

Archaeologists examine a wide variety of artifacts—art, tools, costumes, animal remains, and dwellings—to learn how members of society interacted with one another, how their economies developed, their belief systems, and how they interacted with other societies and their natural environment.

Biological Anthropology

Biological anthropology (sometimes called physical anthropology) is the study of humans as biological organisms.2 Biological anthropologists are interested in the evolution of the human species. In their work, they examine the origin of humans, theories of evolution, how humans historically have interacted with the natural world and each other, and how humans have adapted to their environments. Biological anthropologists also are concerned with contemporary issues concerning human growth, development, adaption, disease, and mortality. Biological anthropologists typically use an interdisciplinary framework for their work: some might rely on the same types of archeological fossils studied by archeologists. Others might borrow methodologies and tools from the biological sciences, while still others will examine human behavior by looking at their closest genetic relatives in the animal world and study primates.

biological anthropology

the study of humans as biological organisms

Linguistic Anthropology

Linguistic anthropology is a method of analyzing societies in terms of human communication, including its origins, history, and contemporary variation and change.3 How individuals speak belies information about the structure and evolution of society. A simple example: If you have studied a romantic language, you will know that many romantic languages have a formal and informal noun meaning “you,” and the level of formality used might be an indication about one’s relationship with the person one is addressing. Studying communication patterns, the creation of dialects indicating the growth of subcultures, and the implicit meaning inherent in linguistic terms (about belief systems, ideologies, religion, and so on), linguistic anthropologists examine how language both reflects human experience with a society, and affects that experience.

linguistic anthropology

a method of analyzing societies in terms of human communication, including its origins, history, and contemporary variation and change

Socio-cultural Anthropology

Socio-cultural anthropology is the study of living peoples and their cultures, including how people live within a given environment. Focusing broadly on various aspects of society from family life to government structures, socio-cultural anthropologists are interested in how societies form and develop. They broadly examine culture, people’s learned and shared behaviors and beliefs or the ways of life that are common to a society. Socio-cultural anthropology often relies on the research methodology of participant observation (as described in greater detail in Chapter 2), in that the researcher both observes and participates in the behavior being studied to gain an intimate look at how individuals within a society work within a certain context.

socio-cultural anthropology

the study of living peoples and their cultures

culture

people’s learned and shared behaviors and beliefs

Because socio-cultural anthropology is particularly interested in similarities and differences between societies across time and space, and the similarities and differences between subsets of populations, we often see socio-cultural anthropological research in the form of comparative analyses. And so, a socio-cultural anthropologist might look at religion in developing versus modern cultures, or differences between men and women in a given tribal society; it provides a perfect framework for our examination of power relations within societies.

Culture: Ways of Life

The culture of any society represents generalizations about the behavior of many members of that society. Culture does not describe the personal habits of any one individual. Common ways of behaving in different societies vary enormously. For example, in some societies arranged marriages are the norm, but such practices are frowned upon in other societies. In some cultures, like those in New Guinea, people paint their entire bodies with intricate designs whereas in others, like the United States, only the faces of the female are painted.

The concept of culture is basic to what anthropology is all about. Anthropologist Clyde Kluckhohn once defined culture as all the “historically created designs for living, explicit and implicit, rational, irrational, and nonrational that may exist at any given time as potential guides for the behavior of man.”4 In contrast with psychologists, who are interested primarily in describing and explaining individual behavior, anthropologists tend to make cultural generalizations. These cultural generalizations focus on aggregate behaviors within a society or values and beliefs that are commonly shared.

cultural generalization

the description of commonly shared values, beliefs, and behaviors in a society

One method of viewing these cultural generalizations is the idea that different cultures are organized around characteristic purposes or themes, a notion popularized by cultural anthropologist Ruth Benedict (1887–1947) in her widely read book Patterns of Culture. According to Benedict, a professor of anthropology at Columbia University, each culture has its own patterns of thought, action, and expression dominated by a certain theme that is expressed in social relations, art, and religion.

For example, Benedict identified the characteristic themes of life among the Zuñi Pueblo Indians of the Southwestern United States as moderation, sobriety, and cooperation. There was little competition, contention, or violence among tribal members. In contrast, the Kwakiutls of the Northwestern United States engaged in fierce and violent competition for prestige and self-glorification. Kwakiutls were distrustful of one another, emotionally volatile, and paranoid. Yet Benedict was convinced that abnormality and normality were relative terms. What is “normal” in Kwakiutlan society would be regarded as “abnormal” in Zuñi society, and vice versa. She believed that there is hardly a form of abnormal behavior in any society that would not be regarded as normal in some other society. Hence, Benedict helped social scientists realize the great variability in the patterns of human existence. People can live in competitive as well as cooperative societies, in peaceful as well as aggressive societies, in trusting as well as suspicious societies.

Today, many anthropologists have reservations about Benedict’s idea that the culture of a society reflects a single dominant theme. There is probably a multiplicity of themes in every society, and some societies may be poorly integrated. Moreover, even within a single culture, wide variations of individual behavior exist.

Subcultures

Generalizations about a whole society do not apply to every individual, or even to every group within a society. In virtually every society, there are distinct variations in ways of life among groups of people. These variations often are referred to as subcultures. They are frequently observed in such things as distinctive language, music, dress, and dance. Subcultures may center on race or ethnicity, or they may focus on age (the “youth culture”) or class (see “Is There a Culture of Poverty?” in Chapter 11). Subcultures also may evolve out of opposition to the beliefs, values, or norms of the dominant culture of society—for example, a “drug culture,” a “gang culture,” or a “hip-hop culture.”

subculture

the variation in ways of life within a society

Multiculturalism

Multiculturalism generally refers to acknowledging and promoting multiple cultures and subcultures. It seeks to protect and celebrate cultural diversity—for example, Spanish-language usage, African American history, and Native American heritage. Multiculturalism tends to resist cultural unification—for example, English-only education, an emphasis on the study of Western civilization, and the designation of “classic” books, music, and art.

multiculturalism

acknowledging, protecting, and promoting multiple cultures and subcultures

Multiculturalism invites students to formally explore the ways of life of their own subculture—Hispanic, African American, Native American, or Asian history, for example. Multiculturalism also enables students to learn about societies other than their own—for example, non-Western cultures of Asia or Africa or traditional cultures of the Mayas or Aztecs. But some criticisms of multiculturalism include that it may denigrate the unifying symbols, values, and beliefs of American society and that it may encourage ignorance of Western European culture, including the foundations of individual freedom and democracy. In doing so, multiculturalism may serve to weaken the dominant “American” culture.

Culture Is Learned

Anthropologists believe that culture is learned, and it is transferred from one generation to another. Culture is passed down through the generations, and cultures vary from one society to another because people in different societies are brought up differently. The process by which culture is communicated is called the socialization process. Some agents that work to teach culture include family, schools, religious organizations, and the media. In these settings, individuals learn from other people how to speak, how to think, and how to act in certain ways.

socialization process

process by which culture is communicated to successive generations

The Components of Culture

Anthropologists often subdivide a culture into various components in order to simplify thinking about it. These components of culture—symbols, beliefs, values, norms, religion, sanctions, and artifacts—are closely related in any society.5

Symbols

Symbols are culturally created and play a key role in the development and maintenance of cultures. A heavy reliance on symbols—including words, pictures, and writing—distinguish human beings from other animals. A symbol is anything that has meaning bestowed on it by those who use it. Words are symbols and language is symbolic communication. Objects or artifacts can also be used as symbols: The symbol of a cross is a visual representation of Christianity; a burning cross is a symbol of hate. The color red may stand for danger, or it may be a symbol of revolution. The creation and use of such symbols enable human beings to transmit their learned ways of behaving to each new generation. Children are not limited to knowledge acquired through their own experiences and observations; they can learn about the ways of behaving in society through symbolic communication, receiving in a relatively short time the result of centuries of experience and observation. Human beings can therefore learn more rapidly than other animals, and they can employ symbols to solve increasingly complex problems. Because of symbolic communication, human beings can transmit a body of learned ways of life accumulated by many people over many generations.

symbol

anything that communicates meaning, including language, art, and music

Beliefs

Beliefs are generally shared ideas about what is true. Every culture includes a system of beliefs that are widely shared, even though there may be some disagreement with these beliefs. Culture includes beliefs about marriage and family, religion and the purpose of life, and economic and political organization (see Case Study: “Aboriginal Australians”). For example, in Saudi Arabia, cultural beliefs are strongly linked to Islam, that country’s predominant religion. There, because Friday is the holy day, many businesses are closed on Thursday and Friday, rather than on Saturday and Sunday. The difference in this culture’s “weekend” is reflective of how beliefs influence a society’s culture.

beliefs

generally shared ideas about what is true

In modern times, beliefs often are more fluid than they have been historically. For instance, in the United States long-held beliefs about many ideas—for example, the role of women in society, racial equality, and homosexuality—have evolved drastically in the past half century. This change in widespread beliefs came about partly because of the increased presence of a common media, but some changes also came about because of a change in values brought about by scientific research and the civil rights and women’s rights movements.

Values

Values are shared ideas about what is good and desirable. Values tell us that some things are better than others. Values provide us with standards for judging ways of life. Values may be related to beliefs as beliefs can justify our values. One case in point: In the United States, the idea of nepotism—showing favoritism to one’s relatives for employment, for example—is often frowned upon. But in Saudi Arabia, nepotism is viewed positively because it means that you are surrounding yourself with known and trusted individuals. This value reflects the belief in Saudi Arabia that family is extremely important, which emphasizes reliance on family as a support structure. There, families provide social and economic networks, and shape nearly all aspects of a Saudi’s life. However, values can conflict with one another (that is, the value of individual freedom conflicts with the need to prevent crime), and not everyone in society shares the same values. Yet most anthropologists believe that every society has some widely shared values.

values

shared ideas about what is good and desirable

Norms

Norms are shared rules and expectations about behavior. Norms are related to values in that values justify norms. If, for example, we value freedom of speech, we allow people to speak their minds even if we do not agree with them.

norms

shared rules and expectations about behavior

CASE STUDY: Aboriginal Australians

Aboriginal Australians lay claim to being the oldest living culture in our world today. Their mark on Australia can be traced back at least 50,000 years when the first inhabitants migrated through Asia across to the ancient continent of Sahul, which once included Australia, New Guinea and Tasmania. Recent research suggests that today’s Aborigines are direct descendants of the first modern humans to leave our ancestral home of North Africa.

The Aborigine belonged to separate bands of semi-nomadic hunter-gatherers, each with its own territory. Over time, they learned to acclimate themselves to Australia’s often harsh environments, caring for the land that fed them and living in communion with their surroundings. Their tracking skills stemmed from an intimate knowledge of Australia’s rivers, mountains, and vast desert land.

When early European settlers first arrived in 1788, there were somewhere between 300,000 to one million indigenous Australians and an estimated 600 different clan groups.

Today, the Aborigine’s connection to the land is the cornerstone of their cultural heritage. They are a deeply spiritual people and the Dreaming, or the Dreamtime, is a complex web of stories that represents their spiritual beliefs as well as their law. In the Dreaming, Ancestor Spirits walked over the land creating animals, plants, bodies of water, and landforms. The Spirits stayed on Earth once they had finished creating, and so the Dreaming never ends. Throughout Australia there are sacred places that represent where Ancestor Spirits have come to rest. Uluru, or Ayers Rock, located in the center of Australia, is the most famous of these. Music, dance, and art are also integral parts of Aboriginal cultural history. They often represent stories of the Dreaming and are created to express the Aborigines’ fight for survival overtime and the kinship they have with all living things.

The norm of tolerance derives from the value that we place on individual freedom. Fairly trivial norms, like lining up at ticket windows instead of pushing to the front, or “staying to the right” in a crowded corridor, are called folkways. Folkways may determine our style of clothing, our diet, or our manners. Mores (pronounced “morays”) are more important norms. These are rules of conduct that carry moral authority; violating these rules directly challenges society’s values. For example, a young Indian couple might challenge an important norm, like arranged marriage, by opting to marry for romantic love. Like values and beliefs, some norms within a given culture conflict with one another and there is substantial variation within individuals’ belief in society’s norms.

folkways

a trivial norm that guides actions

mores

important norms that carry moral authority

Religion

Religion is evident in all known cultures. Although there are differences between societies in the nature of their religious beliefs, all cultures include some beliefs about supernatural powers (powers that are not human and not subject to the laws of nature) and about the origins and meaning of life and the universe. Anthropologists, in their professional roles, do not speculate about the truth or falsehood of religious beliefs. Rather, anthropologists are concerned with why religion is found in all societies and how and why religion varies from one society to another.

religion

a set of beliefs and practices pertaining to supernatural powers and the origins and meaning of life

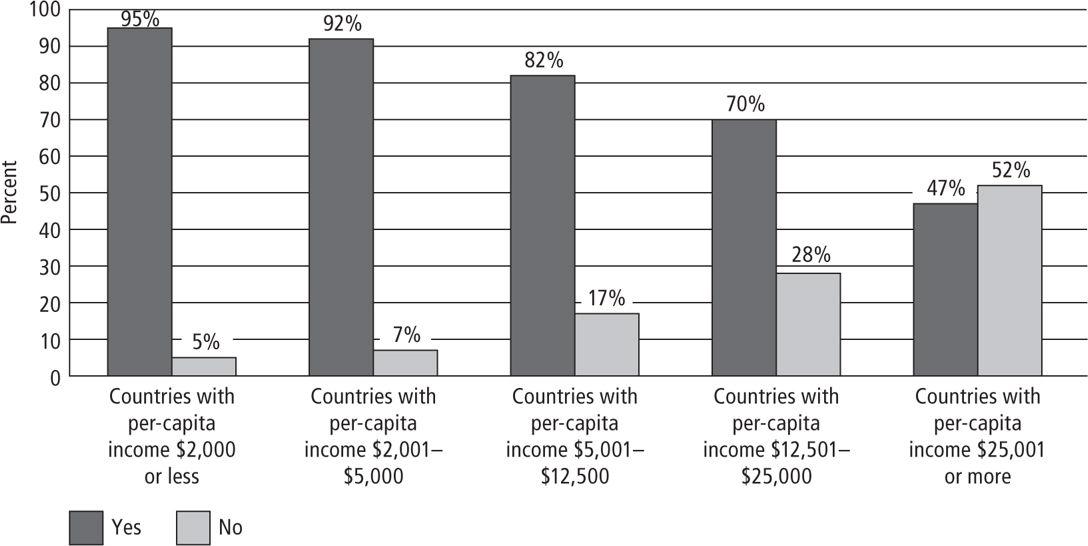

Various theories have arisen about why religious beliefs are universal. Some theories contend that religious beliefs arise out of human anxieties about death and the unknown or out of human curiosity about the meaning, origins, and purpose of life. Religions help us answer universal questions, such as “Why am I here?”, “What is the meaning and purpose of life?”, and “What happens when we die?” Other theories stress the social functions of religion—that it provides goals, purposes, rituals, and norms of behavior for people. Some also assert that for many in the world, particularly the most vulnerable, religion provides hope in what may otherwise be a rather dire existence. For example, Figure 4-1 shows that religion is more important in poorer countries: 95 percent of respondents living in countries with a per capita income of under $2,000 say religion is an important part of their daily life. As income increases, levels of religiosity decrease, with only 47 percent of those in countries with per capita income over $25,000 saying that religion is an important part of their life (see Research This!).

FIGURE 4-1: IS RELIGION AN IMPORTANT PART OF YOUR DAILY LIFE

SOURCE: http://www.gallup.com/poll/142727/Religiosity-Highest-World-Poorest-Nations.aspx

More than 80 percent of the world’s population identify themselves with an organized set of religious beliefs. About 33 percent of the world’s population is Christian. Islamic (Muslims), Hindu, and Buddhist religions combined account for about 40 percent of the world’s population, while Judaism accounts for about 0.2 percent of the world’s population.

Sanctions

Sanctions are the rewards and punishments for conforming to or violating cultural norms. Rewards—for example, praise, affection, status, wealth, and reputation—reinforce cultural norms. Punishments—for example, criticism, ridicule, ostracism, penalties, fines, jail, and executions—discourage violations of cultural norms. But conformity to cultural norms does not depend exclusively on sanctions. Most of us conform to our society’s norms of behavior even when no sanctions are pending and even when we are alone. For example, do you close the bathroom door when you are home alone, with no chance of anyone else entering the house? For society, conformity to society’s norms absent of sanctions means a more orderly existence. For example, most people stop for a red light even at a deserted traffic intersection, making it less likely that an accident will occur. We do so because we have been taught to do so, because we do not envision any alternatives, because we share the values on which the norms are based, or because we view ourselves as part of society.

sanction

a reward or punishment for conforming to or violating cultural norms

RESEARCH THIS!

The table below shows the proportion of people in a given country who indicate that religion is an important part of their everyday lives.

Is religion an important part of your daily life?

Country

Percent Responding “Yes”

Bangladesh

99+

Niger

99+

Yemen

99

Indonesia

99

Malawi

99

Sri Lanka

99

Somaliland region

98

Djibouti

98

Mauritania

98

Burundi

98

Estonia

16

Sweden

17

Denmark

19

Japan

24

Hong Kong

24

United Kingdom

27

Vietnam

30

France

30

Russia

34

Belarus

34

SOURCE: www.gallup.com/poll/142727/religiosity-highest-world-poorest-nations.aspx

YOUR ANALYSIS:

1. Describe the trend in general with regard to the importance of religion to people in various countries when considering income. What might explain this trend?

2. Data not shown on the table is that about two-thirds of Americans—65 percent—say religion is important in their daily lives. How does this information buck the trend indicated by your analysis above? What might explain this?

3. Do you believe that as countries develop, religion becomes less important? Why?

Artifacts

An artifact is a physical product of a culture. An artifact can be anything from a piece of pottery or a religious object from an ancient society to a musical composition, a high-rise condominium, or a beer can from a modern society. But usually we think of an artifact as a physical trace of an earlier culture about which we have little written record. As discussed earlier in this chapter, archeologists try to understand what these early cultures were like from the study of the artifacts they left behind.

artifact

a physical product of a culture

The Nature of Culture

Culture assists people in adapting to the conditions in which they live. Even ways of life that at first glance appear quaint or curious may play an important role in helping individuals or societies cope with problems. Cultural anthropologists rely on four key approaches when examining culture: functionalism, the materialist perspective, idealism, and cultural relativism.

Functionalism

Many anthropologists approach the study of culture by asking what functions a particular institution or practice performs for a society. How does the institution or practice serve individual or societal needs? Does it work? How does it work? Why does it work? This approach is known as functionalism.6

functionalism

a perspective in anthropology that emphasizes that cultural institutions and practices serve individual or societal needs

Functionalism assumes that there are certain minimum biological needs, as well as social and psychological needs, that must be satisfied if individuals and society are to survive. For example, biological needs might include food, shelter, bodily comfort, sexual needs, reproduction, health maintenance, physical movement, and defense.

Social and psychological needs are less well defined, but they probably include affection, communication, education in the ways of the culture, material satisfaction, leadership, social control, security, and a sense of unity and belonging. Given that humans have few inborn instincts on how to meet these biological, social, and psychological needs, culture provides the mechanisms—including social groups and institutions, rules of conduct, and tools—that structure meeting one’s needs within a society. Despite great variety in the way that these needs are met in different cultures, we can still ask how a culture goes about fulfilling them and how well it does so. Functionalists tend to examine every custom, material object, idea, belief, and institution in terms of the task or function that it performs.

To understand a culture functionally, we have to find out how a particular institution or practice relates to biological, social, or psychological needs and how it relates to other cultural institutions and practices. For example, in modern societies, families still can perform numerous biological, social, or psychological functions. Or a society might fulfill its biological need for food by hunting and fulfill its psychological needs by worshiping animals. Although functionalism is not the predominant perspective used by most anthropologists today, it shaped some of the methods and perspectives that are prevalent in contemporary times.

Materialism

Another approach to the study of culture emphasizes the importance of the ways in which humans relate to their social and natural environments. These anthropologists believe that acquiring the materials essential for survival shape the relations that people have with one another and with their environment. Securing their material well-being means that people will attempt to maximize the natural resources at their disposal. Thus, humans form groups to organize the acquisition of material goods, whether through bands of hunters, farming communities, or modern stockbrokers. Anthropologists using the materialist perspective focus on how people make their living in their specific environmental setting.

materialist perspective

a perspective in anthropology that focuses on how people make their living in a specific environmental setting

Some materialist anthropologists emphasize the role of technology, defined as both the tools and the knowledge humans use to overcome their environment and meet their material needs. Technology and the environment impact culture. Thus, technology and the effort to use the environment to fulfill one’s material needs influence a wide variety of practices and social institutions, including marriage practices, family structure, religious practices, economic structures, and political systems. For example, marriage practices within many societies have been regarded in materialist terms, with male suitors evaluated in terms of assets, wealth, and earning potential and females evaluated on the size of the dowry they bring into the marriage. In modern societies today, technology (or the legal and political structure) has codified this materialist view of marriage, allowing for the creation of prenuptial agreements (or “pre-nups”) that specify the distribution of assets should a marriage end.

technology

both the tools and the knowledge humans use to overcome their environment and meet their material needs

Modern materialists also assert that the relationship among technology, the environment, and culture is circular. That is, technology and the environment shape the culture, and the culture adopts practices that may then change technology and the environment, which then reshapes the culture, and so on. The relationship among the three variables is constantly evolving. An example of this can be seen in fishing cultures. When people fished for subsistence, fish were plentiful and the means of catching were relatively simple (net, rod, or spear). As the product of fish becomes more of a commodity, technology changes: bigger fishing vessels, industrial nets, and so on. This also changes the society: Some fishers own boats and can become wealthier; others do not and have a more difficult time making a living. And, of course, the environment changes: Fish become scarcer. But the impact does not stop there: Technology responds by the growth of industrial fisheries rather than private fishers. And the environment continues to respond: Fewer fish still. Culture also responds: Rules on minimum catch size and eventually the replacement of fishing as an occupation with other tasks.

When a population grows and in response to that growth exploits the environment and uses it more intensely, this is a process known as intensification. With intensification, populations use their environment and detrimentally impact it. They then are forced to use energy to meet their material need in other ways and develop creative means of doing so. In short, they use both their environment and their knowledge or labor more “intensely.” This forces cultural change because (1) societies must respond to the changes in technology and use and (2) social relations have necessarily changed between individuals during this process.

intensification

when population growth causes increased use and exploitation of the environment

Idealism

While the materialist approach is important for modern anthropologists, another important perspective in anthropology is idealism. Idealism focuses on the importance of ideas in determining culture. Proponents of idealism believe that the inherent uniqueness of humans and their desire for meaning beyond material well-being is defining and essential to what shapes culture. Indeed, idealists assert that the components of needs and the resources to meet them all are socially constructed (by a culture of ideas). Think of the idea of hunger. In an affluent society, you might ask someone, “Are you hungry for a slice of pizza?” The individual might accept or reject the offer of pizza, depending on absolute hunger or on craving (perhaps she felt like eating a turkey sandwich instead). In other cultures, hunger is hunger and food (whatever is available) satisfies that hunger.

idealism

a perspective in anthropology that focuses on the importance of ideas in determining culture

Idealists assert that people’s perceptions of their environment are important in shaping their relation to it. For example, one society might place a house of worship on the most fertile land or sacrifice valuable resources to a deity. Idealists also assert that how people view resources is culturally determined. Many cultures reject a wide variety of food for religious or cultural reasons: Americans typically reject horsemeat, reptiles, dog and cat meat, insects, and many plants. Both Muslims and Jews reject pork, and Hindus reject beef. To idealists, the social construction of resources that meet material needs indicates the importance of ideas, whether they are religious, cultural, or political, in shaping all other aspects of life. To idealists, the struggle for meaning, the importance of relations between individuals, and the creation of culture and of symbols and intellectual needs drive humans in the creation of culture. Idealists view materialism as a limited (and Western-biased) viewpoint of human motivation.

Using any of these perspectives, anthropology helps us appreciate other cultures. It requires impartial observation and testing of explanations of customs, practices, and institutions. Anthropologists cannot judge other cultures by the same standards that we use to judge our own. Ethnocentrism, or judging other cultures solely in terms of one’s own culture, is an obstacle to good anthropological work.

ethnocentrism

judging other cultures solely in terms of one’s own culture

Cultural Relativity

Cultural relativity—suspending judgment of other societies’ customs, practices, and institutions—enables anthropologists to examine aspects of culture and determine their function within that society. For example, many criticize the policy of the government of the People’s Republic of China that mandates that each couple may have only one child. When examined through an ethnocentric American prism, we would think that such a policy violates one of the fundamental freedoms of individuals. But if we suspend judgment and look at the policy using a cultural relativist perspective, we might determine that given that society’s focus on the needs of the community (rather than individual liberties), the enormous population growth previously seen without population-control policy and the fear on the part of the state that it might not be able to support uncontrolled population growth (with food, jobs, transportation, and housing), then we can see the function that the policy performs within that culture.

cultural relativity

suspending judgment of other societies’ customs, practices, and institutions

However, cultural relativism can lead to moral dilemmas for scholars and students. Although it is important to assess the elements of a culture in terms of how well they work for their own people in their own environment,7 an uncritical or romantic view of other cultures is demoralizing. For example, in China the one-child policy has resulted in rampant abandonment of baby girls. (Sons bear the responsibility of caring for one’s elders in China, thus having a son ensures that the parents will be cared for in their old age.) There also are reports of abortions being performed for the purpose of sex selection in China. In other cultures, a preference for sons has resulted in the practice of female infanticide. Anthropologists might explain the preference for sons in terms of economic production based on hard manual labor in the fields. But understanding the functional relationship between female infanticide and economic conditions must not be viewed as a moral justification of the practice (see Controversies in Social Science: “The World’s Missing Girls”).

Some elements of a culture not only differ from those of another culture but also are better. The fact that all peoples—Asians, Europeans, Africans, Native Americans, and others—have often abandoned features of their own culture in order to replace them with elements from other cultures implies that the replacements served peoples’ purposes more effectively.8 For example, Arabic numerals are not simply different from Roman numerals; they are more efficient. It is inconceivable today that we would express large numbers in Roman numerals; for example, the year of American independence—MDCCLXXVI—requires more than twice as many Roman numerals as Arabic numerals and requires adding numbers. This is why the European nations, whose own culture derived from Rome, replaced Roman numerals with numerals derived from Arab culture (which had learned them from the Hindus of India). So it is important for scholars and students to avoid the assumption of cultural relativity—that all cultures serve their people equally well.9

Authority in the Family

The family is the principal agent of socialization into society. It is the most intimate and important of all social groups. Of course, the family can assume different shapes in different cultures, and it can perform a variety of functions and meet a variety of needs. But in all societies, the family relationship centers on procreative and child-rearing functions. A cross-cultural comparison reveals that in all societies, most families possess these common characteristics:10

Sexual mating

Childbearing and child rearing

A system of names and a method of determining kinship

A common habitation (at some point)

Socialization and education of the young

A system of roles and expectations based on family membership

These common characteristics indicate why the family is so important in human societies. It replenishes the population and rears each new generation.

Within the family, the individual personality is formed. The family transmits and carries forward the culture of the society. It establishes the primary system of roles with differential rights, duties, and behaviors. And it is within the family that the child first encounters authority.

Marriage

To an anthropologist, marriage does not necessarily connote a wedding ceremony and legal certificate. Rather, marriage means a socially approved sexual and economic union between a man and a woman, intended to be more or less permanent and implying social roles between the spouses and their children. Marriage is found in all cultures, and anthropologists have offered a variety of explanations for its universality (see Focus: “Social Science Asks: Is Marriage Becoming Obsolete in America?”). One theory explaining marriage focuses on the prolonged infant dependency of humans. In many cultures, infants are breastfed for up to two years. This results in a division of roles between the female nurturer and the male protector that requires some lasting agreement between the partners. Another theory focuses on sexual competition among males. Marriage minimizes males’ rivalry for female sexuality and thus reduces destructive conflict. Still another theory focuses on the economic division of labor between the sexes. Males and females in every culture perform somewhat different economic activities; marriage is a means of sharing the products of their divided labor.

marriage

a socially approved sexual and economic union between a man and a woman, intended to be lasting, and implying social roles between the spouses and their children

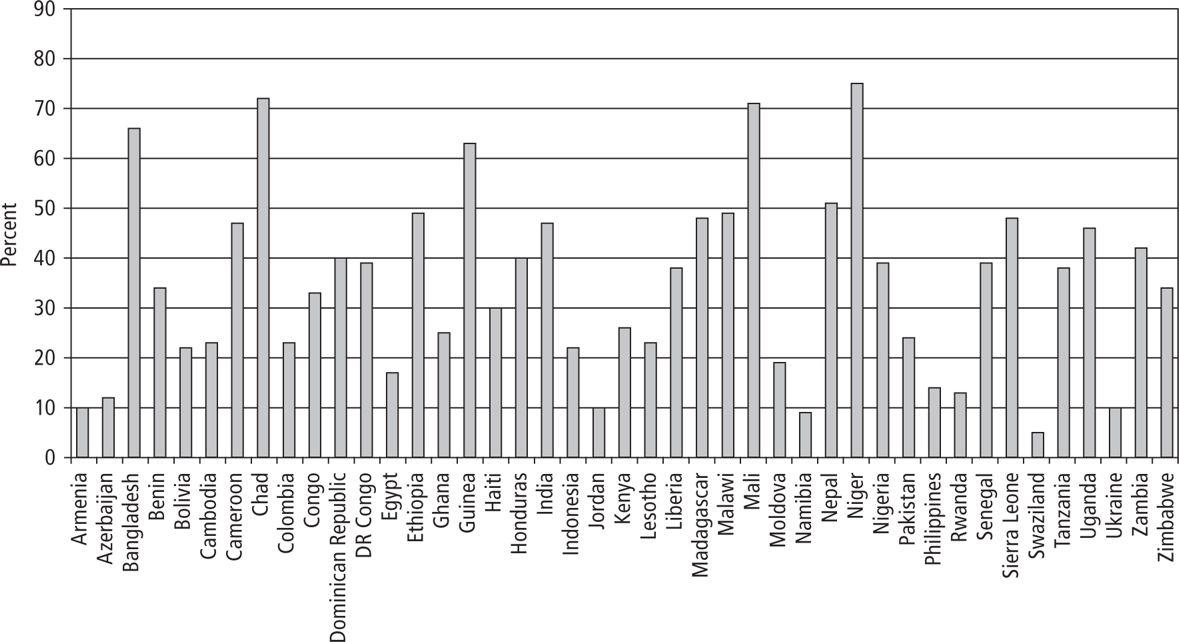

Marriage is found in all cultures, but the institution varies from culture to culture. In some cultures, common practice holds that a girl should be married by the time she is 18 years old. Although UNICEF, the United Nations Children’s Fund, has lobbied against this practice as a violation of human rights, the practice nonetheless continues and is particularly widespread in areas of Africa (Figure 4-2). Oftentimes, parents of girls encourage the marriage of very young daughters—hoping that the marriage, typically to an older and oftentimes better educated man—will benefit both the child and the family financially and socially. At the very least, the marriage of a daughter while still a child alleviates some of the financial burden on the family by placing the financial burden for the upkeep of the girl on the husband. Research indicates that early marriage is detrimental to girls. Girls who married before the age of 18 years are less educated, have more children, and are more likely to experience domestic violence then those who married after age 18.11

FIGURE 4-2: PROPORTION OF WOMEN AGED 20–24 YEARS WHO WERE MARRIED BY THE AGE OF 18 YEARS, SELECTED COUNTRIES

SOURCE: http://www.measuredhs.com/

CONTROVERSIES IN SOCIAL SCIENCE: The World’s Missing Girls

CONTROVERSIES IN SOCIAL SCIENCE: The World’s Missing Girls

In China, there are an estimated 32 million more males than females, an imbalance that appears to be increasing.* In Pakistan, a woman’s in-laws compel her to abort a 4-month-old fetus—her third abortion—because the fetus that she is carrying is female. Newspapers report the new “middle-class trend” in India: relatively inexpensive ultrasound technology used for sex selection. In Zambia, a promising HIV treatment program, antiretroviral therapy (ART), is introduced, but only one-third of the patients are female, despite the higher prevalence of the virus in women there. The following table shows the projected population-to-sex ratio for selected countries for 2011, based on census figures within those nations. The figure for each nation is the number of males per one hundred females. In most industrialized democracies, the number of boy and girl babies born in a given year is roughly equal, with a slight skew toward a few more boy babies. But because women’s life expectancy is longer, the cumulative ratio of females to males is skewed toward there being more females. For instance, on average, females in the United States live about six years longer than men; thus there are more women than men in total.

The table also shows the extent of the problem of missing girls in the selected countries. In parts of some nations—like China, India, and Pakistan—the sex ratio is imbalanced because female fetuses are being aborted. Infant girls also are more likely to be victims of infanticide. The preference for sons is common in many societies. In many agricultural societies, sons are desirable because they will provide labor. In China and parts of India, sons are responsible for their parents’ well-being during old age. Without a government-supported old-age benefit program and with daughters traditionally responsible for the care of their in-laws, many believe that they need a son to survive later in life.

In some societies, the sex imbalance is exacerbated by government policies. For example, for many years China’s one-child policy—intended to control that country’s population growth—was blamed for the sex-ratio imbalance and the abandonment of girls. That policy was called into question when in 2008 a powerful earthquake hit Sichuan Province, killing 70,000 people, including thousands of only children who were buried in the rubble of their schools when the quake hit. In the aftermath of the earthquake, China revised that policy, granting exception to families affected by the earthquake. Families who had lost a child, or whose child was severely injured or disabled in the earthquake, were granted approval to bear another child.

India also offers incentives for smaller families, leaving many to charge that such policies encourage sex-selective abortions because prospective parents limiting the number of children they will have more frequently chose to have male children.

In other societies, the problem of missing girls is due to an inherent lack of value on female life. In some parts of Africa, female children are less likely to be given the basic necessities—including food, potable water, and medicine—in favor of their brothers.

The impact of sex imbalance looks similar despite its numerous causes. In China, “bachelor villages”—inhabited exclusively by bachelor men who cannot find wives—are cropping up. Tens of thousands of women and girls have been kidnapped in China in recent years. The victims are sometimes forced to marry their captors or are sold to another man to become his wife. Experts also say that the sex-ratio imbalance could have dire political consequences, pointing to rebellions that have historically fomented when the sex ratio became imbalanced as groups of young men without the prospect of a family or a future turned against the political system that spawned their situation.

POPULATION SEX RATIO FOR SELECTED COUNTRIES, 2010 (PROJECTED) (MALES PER ONE HUNDRED FEMALES)

United States

97.5

Niger

101.2

Pakistan

103.4

India

106.8

Saudi Arabia

124

China

108

SOURCE: Population Division of the Department of Economic and Social Affairs of the United Nations Secretariat, World Population Prospects: The 2008 Revision and World Urbanization Prospects: The 2008 Revision (http://esa.un.org/unpp/).

* http://newsweek.washingtonpost.com/postglobal/pomfretschina/2009/04/abortions_in_china_girls.html

Romantic Love

Most Americans believe that romantic love should be the basis of a marriage, but this ideal does not characterize marriages in many other societies. On the contrary, in many societies, like India and among some Inuit of Greenland, romantic love is believed to be a poor basis for marriage and is strongly discouraged. (Nonetheless, in most of the world’s societies, romantic love is depicted in love songs and stories.) Marriages based on romance are far less common in less developed societies where economic and kinship factors are important considerations in marriage.12

Monogamy

Family arrangements vary and the marriage relationship may take on such institutional forms as monogamy, polygyny, and polyandry. Monogamy is the union of one husband and one wife; polygyny is the union of one husband and two or more wives; polyandry is the union of one wife and two or more husbands. Throughout the world, monogamy is the most widespread marriage form, probably because the gender ratio (number of males per one hundred females) has been near one hundred in all societies, meaning there is about an equal number of men and women.

monogamy

a marriage union of one husband and one wife

The Family in Agricultural Societies

In most agricultural societies, the family is patriarchal and patrilineal: The male is the dominant authority, and kinship is determined through the male line. The family is an economic institution as well as a sexual and child-rearing one; it owns land, produces many artifacts, and cares for its old as well as its young. Male family heads exercise power in the wider community; patriarchs may govern the village or tribe. Male authority frequently means the subjugation of both women and children. This family arrangement is buttressed by traditional moral values and religious teachings that emphasize discipline, self-sacrifice, and the sanctity of the family unit.

patriarchal family

the male is the dominant authority, and kinship is determined through the male line

Women face a lifetime of childbearing, child rearing, and household work. Families of ten or fifteen children are not uncommon. The property rights of a woman are vested in her husband. Women are taught to serve and obey their husbands and are not considered as mentally competent as men. The husband owns and manages the family’s economic enterprise. Tasks are divided: Men raise crops, tend animals, and perform heavy work; women make clothes, prepare food, tend the sick, and perform endless household services.

The Family in Industrialized Societies

Industrialization alters the economic functions of the family and brings about changes in the traditional patterns of authority. In industrialized societies, the household is no longer an important unit of production, even though it retains an economic role as a consumer unit. Work is to be found outside the home, and industrial technology provides gainful employment for women as well as for men. Typically, this means an increase in opportunities for women outside the family unit and the possibility of economic independence. The number of women in the labor force is increasing today in the United States; about 71 percent of adult women are employed outside the home.

The patriarchal structure that typifies the family in an agricultural economy is altered by the new opportunities for women in advanced industrial nations (see International Perspective: “Women in the Workforce”). Not only do women acquire employment alternatives, but their opportunities for education also expand. Independence allows them to modify many of the more oppressive features of patriarchy. Women in an advanced industrialized society have fewer children, and divorce becomes a realistic alternative to an unhappy marriage.

In advanced industrial societies, governments perform some of the traditional functions of the family, further increasing opportunities for women. For example, the government steps into the field of formal education—not just in the instruction of traditional skills like reading, writing, and arithmetic, but in support of home economics, driver training, health care, and perhaps even sex education, all areas that were once the province of the family. Government welfare programs provide assistance to dependent children when a family breadwinner is absent, unemployed, or cannot provide for the children. The government undertakes to care for the aged, the sick, and others incapable of supporting themselves, thus relieving families of still another traditional function.

FOCUS: Social Science Asks: Is Marriage Becoming Obsolete in America?

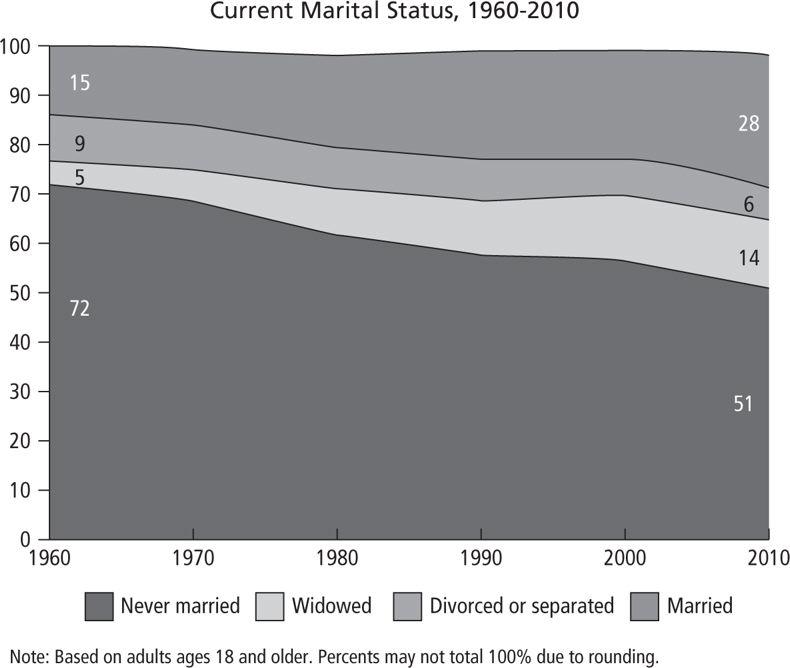

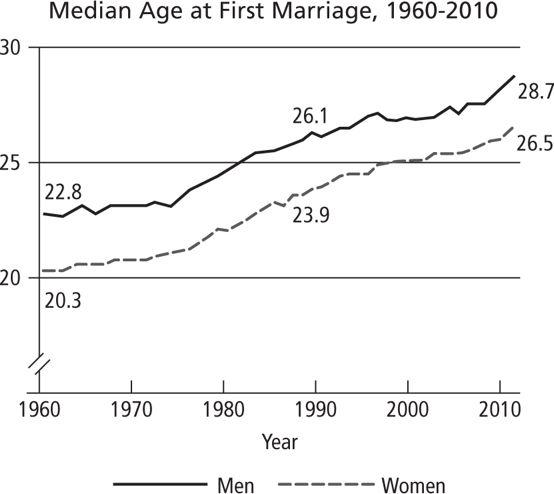

During the past 50 years, there has been a steep decline in the percentage of American adults who are marrying. Part of the explanation is that Americans are marrying later: According to a recent Pew study, the median age for first marriages for both women (26.5) and men (28.7) has never been higher. In 1960, 72 percent of Americans 18 and older were married. Contrast that to 51 percent of Americans today.

American culture has changed over the past few decades, and these changes have spawned some of the decline in marriage. The sexual revolution and women’s movements of the 1960s and 1970s meant that premarital sex became more acceptable and women’s entry into the paid workforce in mass numbers meant that economically independent women had less incentive to marry early. As society continues to change, many college-educated young adults decide to focus on their careers before settling down. There are also a number of alternative living situations that weren’t as prevalent 20, 30, or 50 years ago. Many couples may have children but choose not to get married. There is also a higher number of single-person households and single parenting. Divorce rates are also a factor, though those have leveled off in recent years.

SOURCE: http://www.pewsocialtrends.org/2011/12/14/barely-half-of-u-s-adults-are-married-a-record-low/?src=prc-headline

But more startling is that between 2009 and 2010, new marriages decreased five percent in the United States. That is a drastic change for a one-year period. One explanation for the drastic decline in nuptials that year? The stagnant economy may mean that many young people do not have the financial means for a wedding and for independent living, demonstrating the interrelated nature of various aspects of culture influence society’s behavior and institutions.

SOURCE: http://www.pewsocialtrends.org/2011/12/14/barely-half-of-u-s-adults-are-married-a-record-low/?src=prc-headline

Despite these characteristics of industrial society, however, the family remains the fundamental social unit. The family is not disappearing; marriage and family life are as popular as ever. But the father-dominated authority structure, with its traditional duties and rigid gender roles, is changing. The family is becoming an institution in which both husband and wife seek individual happiness rather than the perpetuation of the species and economic efficiency. Many women still choose to seek fulfillment in marriage and child rearing rather than in outside employment; others decide to do this temporarily. The important point is that now this is a choice and not a cultural requirement.

The American Family

The American family endures. Its nature may change, but the family unit nonetheless continues to be the fundamental unit of society.

Today, there are more than 79 million families in America, and 270 million of the nation’s nearly 312 million people live in these family units.13 About 32 percent of the population lives in nonfamily households, including people with nonfamily roommates and people who live alone.

INTERNATIONAL PERSPECTIVE: Women in the Workforce

INTERNATIONAL PERSPECTIVE: Women in the Workforce

Over time, more and more women have joined the workforce throughout the world. Even in the last twenty years, international statistics indicate that the world’s female workforce has increased rapidly.

In the United States, the percentage of women working outside the home rose from 31 percent in 1950 (not shown in the accompanying table) to nearly 60 percent in 1980 and over 70 percent today. Virtually all other industrialized nations have experienced similar increases in the percentage of women in the workforce. Nonetheless, fewer than half of women in some nations (for example, Italy, Mexico, and Turkey) are included in the workforce. In contrast, women in Scandinavian nations (Finland, Iceland, Norway, and Sweden) have long had higher workforce participation rates than American women.

Country

1980

1990

2000

2009

Australia

52

62

66

71

Austria

49

55

62

70

Belgium

47

52

57

61

Canada

57

68

70

74

Czech Republic

(X)

69

64

62

Denmark

71

78

76

77

Finland

70

74

72

74

France

54

60

65

66

Germany1

53

57

64

71

Greece

33

44

50

55

Hungary

(NA)

(NA)

52

55

Iceland

(NA)

(NA)

83

80

Ireland

36

44

57

64

Italy

40

46

47

52

Japan

55

60

64

69

Korea, South

46

51

55

58

Luxembourg

40

50

70

96

Mexico

34

23

43

47

Netherlands

36

53

66

74

New Zealand

45

65

68

74

Norway

62

71

76

78

Poland

(NA)

(NA)

61

57

Portugal

55

62

67

73

Slovakia

(X)

(X)

63

61

Spain

32

42

52

65

Sweden

74

81

75

78

Switzerland

54

66

77

83

Turkey

(NA)

37

30

29

United Kingdom

58

66

68

70

United States

60

69

71

70

SYMBOL:

NA Not available.

X Not applicable.

SOURCE: Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), 2011, “Labour Market Statistics: Labour Force Statistics by Sex and Age: Indicators,” OECD Employment and Labour Market Statistics database (copyright).

Female Labor Force Participation Rates, by Country [in percent]

FOOTNOTES:

1Prior to 1991, data are for former West Germany.

(Harrison 72-95)

Harrison, Brigid C. Power and Society: An Introduction to the Social Sciences, 13th Edition. Cengage Learning, 20130115. VitalBook file.

The citation provided is a guideline. Please check each citation for accuracy before use.

The rapidly changing nature of families in the United States can be seen in this photo. Here, a gay couple cares for their children. In the middle of the twentieth century, divorce and single-parent families were relatively rare. Today, the American family is a flexibly defined unit.

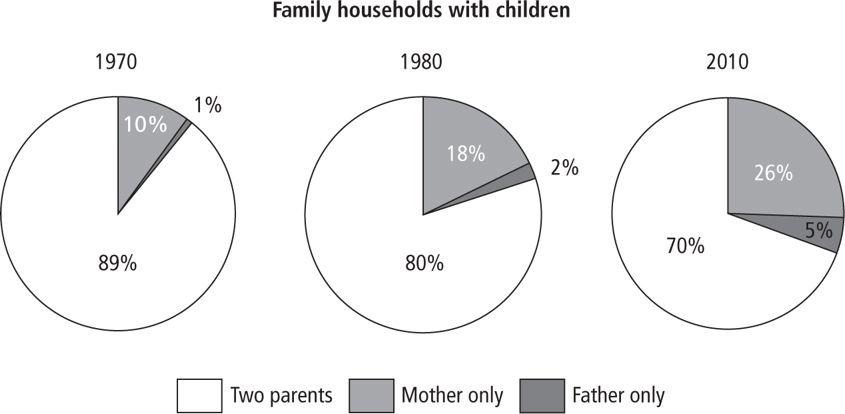

However, the nature of the family unit has indeed been changing. Husband–wife families comprise 70 percent of all families with children, whereas 30 percent of all families consist of a single adult and children. Female-headed families with no spouse present have risen from 10 percent of all families with children in 1970 to 26 percent of all families in 2010 (Figure 4-3). The birth rate also demonstrates how American families are changing: In the 1950s, the fertility rate for the average woman of childbearing age was 3.7 births. In the 1970s, that dropped to 2.4, and continued to fall, reaching a low of only 1.8 in 2000, which is below the projected zero-population growth rate (2.1 children per female of childbearing age). By 2011, the birth rate had climbed to 2.06, reflecting another change in the structure of the American family, with record numbers of births to unmarried women of all ages.14

FIGURE 4-3: THE CHANGING AMERICAN FAMILY

SOURCE: http://www.census.gov/compendia/statab/2012/tables/12s0067.pdf

It is not really clear what factors are contributing to these changes in the American family. Certainly, new opportunities for women in the occupational world have increased the number of women in the workforce and altered the traditional patterns of family life. Economic concerns may be an even more important factor: Families must increasingly depend on the incomes of both husband and wife to maintain a middle-class lifestyle.

Divorce

Almost all societies allow for the separation of husband and wife. Many developing societies have much higher divorce rates than the United States and other advanced industrialized societies. In 2011 in the United States, there were 3.4 divorces for every 7.5 marriages (per 1000 total population).15 At this rate, we would expect half of all marriages to end in divorce. The U.S. divorce rate has decreased somewhat in recent years; it was higher at 5.2 divorces per 1000 population in 1970. The median duration of marriages that end in divorce is seven years, but not all marriages are created equal: First marriages are less likely to end in divorce, while the odds of divorce increase with subsequent marriages. Researchers believe that part of the explanation for the declining divorce rate in the United States is because Americans are more likely to live together without marrying today than in earlier decades, and those who do marry are likely to marry at an older age—on average five years older—than in the 1960s. Both of these factors also help explain why the United States’ divorce rate is lower than that found in many developing nations, where people are likely to marry younger and not live together without marrying.

Women are more heavily burdened by divorce than men. Most mothers retain custody of children. Although both spouses confront reduced family income from the separation, the burden falls more heavily on the mother who must both support herself and rear the children. Divorced fathers are generally required by courts to provide child support payments; however, these payments rarely amount to full household support, and significant numbers of absent fathers fail to make full payments. Most divorced persons eventually find new spouses, but these remarriages are even more likely to end in divorce than first marriages.

Power and Gender

Although some societies have reduced sexual inequalities, no society has entirely eliminated male dominance.16 Role differentiation in work differs among cultures. Sometimes, role differentiation occurs because of sex-based differences, or biologically rooted differences, between men and women. For example, the practice of women working close to home sometimes stems from women’s biological need to be close to their young children in order to nurse them. Other differences are gender-based differences derived from society’s cultural expectations based on accepted norms. For example, the historical tendency of men becoming physicians while women became nurses was based on gendered expectations. Moreover, historically, comparisons of numbers of different cultures studied by anthropologists reveal that men rather than women traditionally have dominated in political leadership and warfare. Though women are an increasing presence in world politics, even today, women on the average make up only about 17 percent of the representatives in national legislative bodies (congresses and parliaments) around the world,17 and in no country have women achieved representation comparable to their proportion of the population.

sex-based differences

biologically rooted differences between men and women

gender-based differences

the cultural characteristics linked to male and female that define people as masculine and feminine

Why have men dominated in politics and war in most cultures? There are many theories on this topic. Many theories link men’s and women’s participation in politics to their participation in war. For example, a theory of physical strength suggests that men prevail in warfare, particularly in primitive warfare, which relies mainly on physical strength of the combatants. Because men did the fighting, they also had to make the decisions about whether or not to engage in war; thus, men were dominant in politics. Decisions about whether to fight or not were vital to the survival of the culture; therefore, decisions about war were the most important political decisions in a society. Dominance in those decisions assisted men in other aspects of societal decision making and led to their general political dominance.

A related hunting theory suggests that in most societies, men do the hunting, wandering far from home and using great strength and endurance. The skills of hunting are closely related to the skills of war; people can be hunted and killed in the same fashion as animals. Because men dominated in hunting, they also dominated in war.

A childcare theory argues that women’s biological function of bearing and nursing children prevents women from going far from home. Infants cannot be taken into potential danger. (As we stated earlier in this chapter, in most cultures women breastfeed their children for up to two years.) This circumstance explains why women in most cultures perform functions that allow them to remain at home—for example, cooking, harvesting, and planting—and why men in most cultures undertake tasks that require them to leave home—hunting, herding, and fishing. Warfare of course requires long stays away from home. In addition, the different nature of these functions—that men’s work tends to take place in public and in groups and women’s work tends to center around children and the home—leads to the evolution of what has been called the public–private split. The public–private split is the idea that men dominate in the public sphere and women focus on the private or domestic sphere. Thus, men are more likely to dominate in politics because they have more experience in the public sphere.

public–private split

the theory that men dominate in the public sphere and women focus on the private or domestic sphere

Still another theory, an aggression theory, proposes that men on the average possess more aggressive personalities than women. Some anthropologists contend that male aggression is biologically determined and occurs in all societies. They point to evidence that even at very young ages, boys try to hurt others and establish dominance more frequently than girls; these behaviors seem to occur without being taught and even when efforts are made to teach boys just the opposite.18

All these theories are arguable, of course. Some theories may be thinly disguised attempts to justify an inferior status for women—for keeping women at home and allowing them less power than men. Moreover, these theories do not go very far in explaining why the status of women varies so much from one society to another.

Although these theories help explain male dominance, we still need to explain the following: Why do women participate in politics in some societies more than in others? Generally, women exercise more political power in societies where they make substantial contributions to economic life. Thus, women have less power in societies that depend on hunting or herding and appear to have less power in societies that frequently engage in warfare. They also exercise more power in societies where societal views determine that women’s participation in politics is acceptable and in societies where women have the opportunity to take part in educational and economic activities that lead to participation in politics. Some evidence suggests that the type of electoral system influences women’s participation in politics. Finally, some evidence shows that women have more power in societies that rear children with greater affection and nurturance because women’s work is held in higher esteem.19

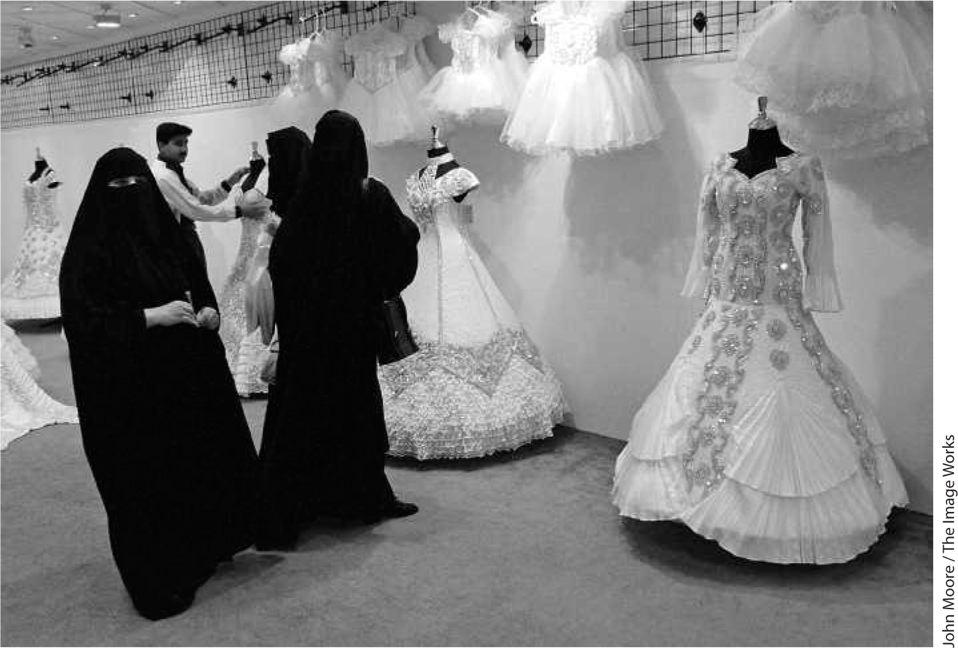

Saudi women shop for wedding dresses in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. Although Saudi women must wear the abaaya in public places, they can dress more liberally at private family gatherings.

Power and Political Systems

The political system is the way that power is organized and distributed in a society, whether it is organizing a hunt and designating its leader or raising and commanding an army of millions. Some form of political system exists in all societies.20

political system

the organization and distribution of power in society

Anthropologists have identified various types of political systems. These systems can be arranged according to the extent to which power is organized and centralized, from family and kinship groups to bands, tribes, chiefdoms, states, and nations.

Family and Kinship Groups

In some societies, no separate power organization exists outside the family or kinship group. In these societies, there is no continuous or well-defined system of leaders over or above those who head the individual families. These societies do not have any clear-cut division of labor or economic organization outside the family, and there is no structured method for resolving differences and maintaining peace among members of the group. Further, these societies do not usually engage in organized offensive or defensive warfare. They tend to be small and widely dispersed, have economies that yield only a bare subsistence, and lack any form of organized fighting force. Power relationships are present, but they are closely tied to family and kinship. An example of this type of society is the Inuit, a people who inhabit the coastal areas of Arctic North America, Siberia, and Greenland. Family and kinship groups are the most important structure: The division of labor is based at the family level (and is determined by sex). Ostracism is the most prevalent method of social control.

Bands

Bands are small groups of related families of usually fewer than 75 people who occupy a common territory and come together periodically to hunt, trade, and make marriage arrangements. Bands are often found among nomadic societies where groups of families move about the land in search of food, water, game, and subsistence.

band

a small group of related families who occupy the same territory and interact with one another

Anthropologists believe that bands were the oldest form of political organization outside of the family and that all humans were once food foragers who moved about the land in small bands numbering at most a hundred people.

Authority in the band is usually exercised by a few senior heads of families; their authority most often derives from achievements in hunting or fighting. The senior headmen must decide when and where to move and choose a site for a new settlement. People follow the headmen’s leadership primarily because they consider it in their own best interest to do so. Sanctions may range from contempt and ridicule to ostracism or exile from the band.

Tribes

Anthropologists describe tribes as groups of bands or villages that share a common language and culture and unite for greater security against enemies or starvation. (Tribe also has a distinct legal definition in the United States, referring to recognized political organizations of Native Americans. See “Native Americans: An Historical Overview” in Chapter 10.) Typically, tribes are engaged in hunting, herding, or farming, and they live in areas of greater population density than bands. Tribal authorities must settle differences between bands, villages, and kinship groups. They must organize defenses as well as plan and carry out raids on other tribes. They must pool resources when needed and decide upon the distribution of common resources—the product of an organized hunt, for example. Authority may rest in the hands of one or more leaders respected for age, integrity, wisdom, or skills in hunting and warfare.

tribe

a group of separate bands or villages sharing a common language and culture who come together for greater security

Chiefdoms

Anthropologists also identify chiefdoms—highly centralized, regional societies in which power is concentrated in a single chief who is at the head of a ranked hierarchy of people. An example of a chiefdom is Akan, a chiefdom that dominated politics in areas now part of Ghana and the Ivory Coast. The position of chief is usually hereditary. People’s status in the chiefdom is decided by their kinship to the chief; those closest to him are ranked socially superior and receive deferential treatment from those in lower ranks. The chief’s responsibilities extend to the distribution of land and resources, the recruitment and command of warriors, and control over the goods and labor of the community. The chief may amass considerable personal wealth and other evidence of his high status.

chiefdom

a centralized society in which power is concentrated in a single chief who heads a ranked hierarchy of people

States

The most comprehensive and complex system of power relationships is the state. A state is a permanent, centralized organization with a well-defined territory and the recognized authority to make and enforce rules of conduct. The power of the state is legitimate; that is, the state has the rightful use of power within a society. In state societies, populations are large and highly concentrated; the economy produces a surplus; and there are recognized rules of conduct for the members of the society, with positive and negative sanctions. These societies have an organized military establishment for offensive and defensive wars. In war, conquered people are not usually destroyed but instead are held as tributaries or incorporated as inferior classes into the state. In the vast majority of these societies, power is centered in a small, hereditary elite (see Focus: “Power and the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia” on p. 102).

state

a permanent centralized organization with a defined territory and recognized authority to make and enforce rules

Power in the state is employed to maintain order among peoples and to carry on large-scale community enterprises, just as in the band or tribe. But power in the state is also closely linked to defense, aggression, and the exploitation of conquered peoples. Frequently, states emerge in response to attacks by others. Where there is a fairly high density of population, frequent and continuing contact among bands, and some commonality of language and culture, there is the potential for “national” unity in the form of a state. But a state may not emerge if there is no compelling motivation for large-scale cooperation. Motivation is very often provided initially by the need for defense against outside invasion.

Nations

A nation differs from a state in important ways. A nation is a society that sees itself as “one people” with a common culture, history, institutions, ideology, language, territory, and (often) religion. By this definition, there are probably five thousand or more nations in the world today. (The United Nations has only 192 member states; see Chapter 14.) Only rarely do nation and state coincide, as in Japan, which has a relatively homogenous population within its territory. Because of migration, trade, and war, many states are much more heterogeneous. Some states do not have a nation of their own but exist within the borders of other nations. An example of a stateless nation is that of the Kurds, who occupy land in a variety of states, including Iraq and Turkey. Many states are multinational, that is, they include within their territorial boundaries more than one nation. When a state and nation do coincide, it is usually referred to as a nation-state.

nation

a society that sees itself as one people with a common culture, history, ideology, language, set of institutions, and territory

The United States declares itself to be “one nation, indivisible, under God,” yet it encompasses multiple nationalities, languages, and cultures. The claim to nationhood by the United States rests primarily on a common allegiance to the institutions of democracy. Similarly, the nations of Russia and China are composed of a variety of peoples who identify with national institutions. Other nation-states base their claim to nationhood on common ethnicity and ancestry as well as language and territory.

Power and Society: Some Anthropological Observations

Let’s summarize the contributions that anthropological studies can make to our understanding of the growth of power relationships in societies. First, it is clear that the physical environment plays an important role in the development of power systems. Where the physical environment is harsh and the human population must out of necessity be spread thinly, power relationships are restricted to the family and kinship groupings. Larger political groupings are essentially impossible. The elite emerge only after there is some concentration of population where food resources permit groupings of people larger than one or two families.

Second, power relationships are linked to the economic patterns of a culture. In subsistence economies, power relationships are limited to the band or tribal level. Only in surplus-producing economies do we find states or statelike power systems. Developed power systems are associated with patterns of settled life, a certain degree of technological advance, and economic surplus.

FOCUS: Power and the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia

The Kingdom of Saudi Arabia is a state: It has a defined territory and recognized authority to make and enforce laws. But the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia is also an excellent example of a chiefdom. In 1902 Abd al-Aziz Ibn Saud captured the city of Riyadh (now the capital) and began a quest to unite the Arabian Peninsula, which occurred on September 23, 1932. It is within the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia that one finds two of Islam’s holiest cities: Mecca and Medina.