Peer review Worksheet on Research Project

Running Head: GENDER BIAS

Gender Bias Toward Female Education

Margaret Weir

LIB 495 Capstone - Advanced Research Project

Instructor: Justin Brumit

May 30, 2017

Gender Bias Toward Female Education

Throughout the years, gender bias toward female education has been a problem, primarily in the science, technology, engineering, and math areas, or STEM, as they are known. STEM fields of study, along with other areas, are both encouraged and discouraged by teachers and parents, as well as cultures, based on gender. While some believe this not to be true, others feel gender bias is a major concern and solutions to this problem need to be established and reinforced.

Problem

Beginning in pre-school and continuing through college, gender bias in the classroom is a significant, worldwide problem that teachers and schools show toward students, mainly females. While some believe this to be true, others believe the contrary. They feel that gender bias in the classroom no longer exists; that the educational gaps, between boys and girls, have closed since 1970. They also contend that boys are often overlooked and not more accommodated than girls. Some feel that even though girls still lag behind boys in mathematics and science, girls do better in reading, writing, and other subjects; earn more credit; are more likely to get honors; and are more likely to further their education at colleges or universities (Lynch, 2016, para. 6). Through research, however, it has been shown how teachers show gender bias toward female students in the classroom in various ways, such as:

Spending more time with their male students than they do with their female students, which leads to girls feeling inferior to boys and hindering their educational advancement. Also, teachers tolerate behavior in boys that they do not tolerate in girls, and tend to provide boys with more criticism and praise (Lynch, 2016). Boys are more likely to receive attributions to effort and ability, and teacher comments, giving them confidence that success and competence is simply a matter of applying themselves; however, girls are often told, "It’s okay, as long as you try”. Calling more boys than girls to the front of the class to do demonstrations, giving more positive feedback and remediation to males, and allowing males to speak over females (DSEA, 2010), are other ways in which teachers show inequality in the classroom.

Teacher Gender Prejudices

Teacher bias toward female students has been, and still is, negatively influencing girls’ education. Female students are less involved in the classroom, have lower self-esteem and confidence, and limit their career goals because of gender bias. In one study, it shows how students interact with their teachers by different forms of communication – written, verbal, and non-verbal, and the relationship between communication and gender bias. And, even though teachers try to be fair to all students, they tend to communicate more with their male students than their female students, spending, on an average, 56 percent of their time with males and 44 percent with females (Simmons, 1998). It also has been found that teacher biases, whether consciously or unconsciously, have caused the United States to have one of the world’s largest gender gaps in STEM-related performance.

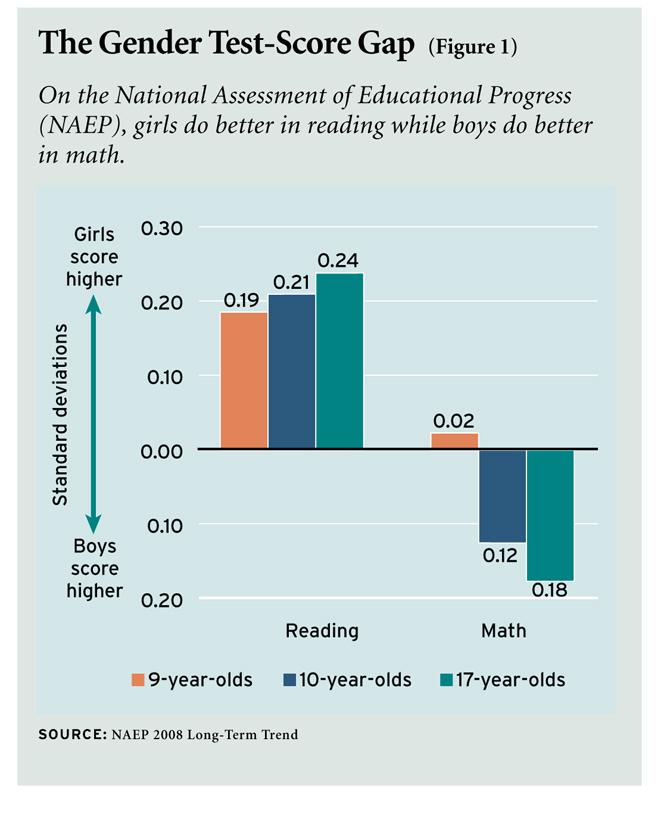

Research also has shown that teachers present their students with a curriculum that contain gender stereotypes, and how a teacher’s gender prejudices shape classroom behaviors. Moreover, it has been reported as to how an environment, such as a classroom, influences children’s prejudices and stereotyping. When teachers use both gender-based segregation and sexist language, such as “only girls should play with dolls”, “good morning boys and girls”, or “when boys and girls need to wear different-colored robes at a commencement ceremony” (Hilliard & Liben, 2010, page 1788), this affects children in a negative way, and they continue to encounter experiences that increase the salience of gender. The assumption that girls are better at art, music, reading, writing, and grammar, leads them often to be pushed in that direction. It also is portrayed as if girls struggle in the STEM-related courses, as well as physical education, history, and applied arts; whereas, boys are more encouraged in these subjects. Furthermore, the negative stereotypes of girls lower their career aspirations in the science, technology, engineering, and math fields. As seen in Figure 1, the NAEP (2008), shows that, as they age, girls do better in reading while boys do better in math.

Bias Classroom Reading Materials

Classroom reading materials also influence children and their views of male and female roles in society. Reading materials that children are exposed to in a classroom affect students in negative ways. Many classroom materials do not show females in positive roles and give the message that females are less valuable than males. Studies have shown that children’s reading materials devalue females across various areas of sexism; such as, negative attitudes toward women, beliefs about women that reinforce inferiority, and acts of exclusion directed toward women. At a time when women and men are viewed as equals by much of the population, bias is still evident in the readers and literature that children are exposed to (Witt, 2001, para. 17). For example, it has been found that in American children’s books:

- there are 2.3 males in the title for every female.

- there are 2.9 male adult central characters for every female.

- there are 2.4 male child central characters for every female.

- there are 4.3 male animal central characters for every female.

- in books that won the Caldecott Medal, ten boys are pictured for every girl (Weiss, 1991).

Many books that children use in school are filled with racial, ethnic, social class, and gender stereotypes, and influence children in negative ways. For example, an examination of 113 published books for children found that dependency themes which emphasize helpless behavior for females continue to be commonly used (White, 1986). Moreover, most cultures use storytelling to transmit values and attitudes to children; this includes stories found in children’s readers (Kortenhaus & Demarest, 1993). Because the books children read in school play such a potentially important defining role in their lives, it is natural to expect that the attitudes and values exhibited in them will be accepted by the children who read them. As children grow older, they are praised and rewarded for conforming to society’s expectations of gender-stereotyped behaviors. Furthermore, it has been shown that children who are exposed to books with gender stereotypic behaviors are more likely to demonstrate stereotypic behaviors (Ashton, 1983). Teacher bias, children’s reading materials, and negative stereotyping can hamper female educational advancement. Also, female students’ negative attitudes toward science, technology, engineering, and math-related courses can lower their aspirations for future careers in STEM fields.

STEM-Related Attitudes

Studies have shown how boys and girls differ in their perceptions and attitudes toward science, scientists, and science-related careers. Girls see science as difficult; whereas, science is considered more suitable for males. It also has been shown that, as early as elementary school, boys show more interest in science and become even more interested between the ages of 10-14, while girls show little interest in science. In a study of gender and students’ science interests, Kahle examined data from the National Assessment of Educational Progress and found that girls described their science classes as “facts to memorize,” and “boring” (Kahle & Lakes, 1983). Moreover, Catsambis (1995) found that males were more likely to look forward to science class, to think science would be useful to their future, and were less afraid to ask questions in science classes than their female peers. Feminist theories, also, have shown that science-related experiences are different for girls during childhood through adolescence; such as, within the same classroom, boys have more opportunities to conduct experiments and demonstrations, and utilize science equipment. Also, studies show that boy’s and girl’s cultures shape their attitudes toward science, where science is more appropriate for boys, and these beliefs are brought to school by boys. In a 1999 study by Jones, Howe, and Rua, it was found boys and girls everywhere are embedded in their culture and are shaped by it, and if their culture conveys the ideas that science is more appropriate for boys than for girls, it is likely that adolescents will bring these values and attitudes to school (Jones, et al., 1999). Technology and engineering also are perceived as male-dominated.

Why, when considering technology or engineering, does society think of these fields as ones mostly for males and not females? Why is this the mindset of most people? The answer is simple; from a young age, boys are mostly thought of as having an interest in technology and science (i.e. playing with robots, block building, playing electronic games), and are encouraged both by parents and teachers to pursue these interests. However, young girls are encouraged in humanities (i.e. playing house, playing “mommy” with baby dolls, playing dress-up). Boys, also, are stereotyped as being better at science and math, which can discourage girls from STEM-related courses. Moreover, girls become discouraged because there are not many role models in these fields. Research has shown that 74% of girls in middle school express an interest in STEM subjects. However, only 0.4% of girls in high school actually choose computer science as a college major, and only 18% of computer science graduates are female. Research also has shown that “people often hold negative opinions of women in ‘masculine’ positions, like scientists or engineers (Hill, et al., 2010, pg. 28). “Gender gaps in technology contribute to at least three forms of gender inequality: (I) unequal access to knowledge, training, and employment, particularly decent work; (II) unequal opportunities for self-discovery, social and professional relationship-building; and (III) unequal understanding of legal rights and modes for civic participation (Intel 2012; UNESCO 2013). This impacts all facets of life — from perceptions of one’s capabilities to the development and realization of those capabilities” (Warnecke, 2017, pg. 308). Negative attitudes toward science, technology, engineering, and math can deter girls from going towards college degrees and careers in these fields.

Concerning math, reviews have shown how parents’ and teachers’ expectancies for children’s math competence are often gender-biased and can influence children’s math attitudes and performance (Gunderson, et al., 2012). Parents of boys tend to believe that their child has higher math ability and expect their child to achieve more in math than parents of girls (Eccles et al. 1990; Yee and Eccles 1988). They also believe that boys have more natural talent in math, anticipate that boys will have greater future success in careers requiring math skills, rate the importance of math as greater for boys than for girls, and rate math as more difficult for girls than for boys (Eccles et al. 1990). Teachers also show gender-stereotyped beliefs about their students’ math abilities. They perceive male students as being more logical, more competitive, more independent in math, and liking math more than their female students (Fennema et al. 1990). Teachers also believe that boys have greater math ability than girls, that boys are more capable of logical thought than girls, and that math is a more difficult subject for girls than for boys (Tiedemann 2000a, b, 2002). Furthermore, research has shown that negative stereotypes about girls and their abilities in math do indeed lower their math test performance.

Bias toward females in the STEM fields does not end in high school; it continues even into college. Surveys conducted in the U.S. indicate that about 40 % of teachers and 50 % of students have witnessed an incident of bias in college classrooms (Boysen and Vogel 2009; Boysen et al. 2009). Classroom bias tends to be subtle rather than blatant, and stereotypes are the most common type of bias (Boysen et al. 2009). The number of women in STEM areas is growing, yet men continue to outnumber women. In elementary, middle, and high school, girls and boys take STEM courses in roughly equal numbers, and about as many girls as boys leave high school prepared to pursue STEM majors in college; however, fewer women than men pursue such majors. Among first-year college students, women are much less likely than men to say that they intend to major in science, technology, engineering, or math, and by graduation, men outnumber women in nearly every STEM field. According to a report released by the National Center for Education Statistics (updated March 1, 2017), there was a total of 2,263,446 degrees awarded nationwide (662,079 Master’s Degrees and 1,601,367 Bachelor’s Degrees.) As seen below, of the Master’s Degrees, most of the STEM-related Degrees were earned by men; whereas, women earned more Master’s Degrees in the humanities fields.

Most Popular Master’s Degrees for Men

| Degree | # of Degrees | % of Total | |||

| Business Administration and Management | 58,766 | 22.3 | |||

| Electrical, Electronics and Communications Engineering | 7,462 | 2.8 | |||

| Educational Leadership and Administration | 7,139 | 2.7 | |||

| Business/Commerce | 6,461 | 2.5 | |||

| Education | 5,832 | 2.2 | |||

| Accounting | 5,314 | ||||

| Public Administration | 4,181 | 1.6 | |||

| Computer Science | 3,980 | 1.5 | |||

| Mechanical Engineering | 3,929 | 1.5 | |||

| Computer and Information Sciences | 3,718 | 1.4 |

Most Popular Master’s Degrees for Women

| Degree | # of Degrees | % of Total | |||

| Business Administration and Management | 45,366 | 11.4 | |||

| Education | 20,225 | 5.1 | |||

| Social Work | 16,716 | 4.2 | |||

| Elementary Education and Teaching | 15,213 | 3.8 | |||

| Curriculum and Instruction | 14,276 | 3.6 | |||

| Educational Leadership and Administration | 13,086 | 3.3 | |||

| Special Education and Teaching | 11,763 | %3 | |||

| Counselor Education/School Counseling | 10,532 | 2.6 | |||

| Nursing (RN, ASN, BSN, MSN) | 8,276 | 2.1 | |||

| Reading Teacher Education | 7,948 |

Source: National Center for Education Statistics. (2017).

Female students not only can be discouraged by teacher bias, reading materials, and negative attitudes toward STEM subjects, their culture also can be an educational barrier.

Cultural Influences

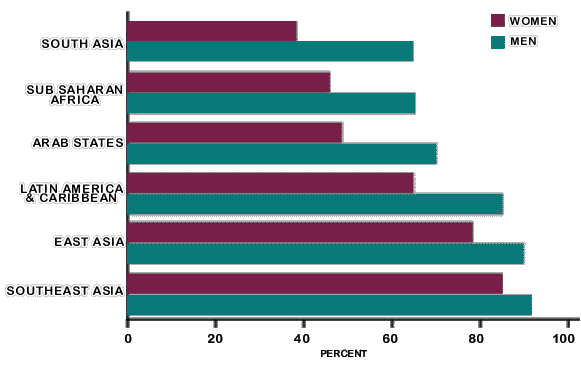

Cultures, worldwide, can influence an individual’s values, beliefs, attitudes, and customs, as well as hinder a female’s education. For instance, in India, education is not seen as a necessity for girls. Their parents might consider it more important, that they learn domestic chores, as they will need to perform them for their future husbands and in-laws. Another disincentive for sending daughters to school is a concern for the protection of their virginity. When schools are located at a distance, when teachers are male, and when girls are expected to study along with boys, parents are often unwilling to expose their daughters to the potential assault on their virginity, that would ultimately result in an insult to the girl's family's honor. This results in one of the lowest female literacy rates in the world; Literacy Rate for Women: 54%, Literacy Rate for Men: 76% (Saarthak, n.d., para. 7). Like India, African culture also can hinder a female’s education. Per Norah Mwaiko (2017), in Kenya, where cultural beliefs are involved, the girl-child falls victim to violation of her rights, including her rights to education. Many girls are forced into early marriages, experience Female Genital Mutilation, and sexual exploitation, among many other concerns, and at some point, they all lead to her inability to achieve her education. Research indicates that socio-cultural factors tend to affect the girl-child's access to education more than other factors (Graham Brown, 1991). In the pastoral communities, for instance, certain rituals practiced in the community are major obstacles for girls in accessing education. Moreover, according to Ombati, et al. (2012), poverty is the single largest factor that causes disparities in education. He explains that poverty is pervasive across the sub-Saharan African region, and there is a strong association between poverty and gender inequalities in education. In most cases where the family faces financial constraints, parents preferred educating the boys as they tended to believe that educating the girl child is expensive as she requires more than just books, uniforms and some personal items like sanitary towels. Furthermore, many parents believe a girl will at some be married and will leave the family; therefore, her education would not benefit her family of orientation. As seen in the graph below, females are outnumbered by males in literacy, per country, due to the lack of education.

Source: UNESCO. (2010)

As shown, females, from a young age through college-age, are treated quite differently than boys, and have a difficult time in certain areas of study. Biases, prejudices, stereotypes, and discrimination all contribute to a feeling of inferiority with regards to a female’s educational and career achievements in various fields, especially ones which are STEM-related. However, according to some, there are solutions to this gender gap which teachers, parents, and third world countries can adhere to that could slow down or end this worldwide problem.

Solutions

For Teachers in Elementary School Through Grade 12

Researchers believe that negative stereotypes can lower girl’s aspirations for careers in STEM-related fields; however, if learning environments were to change, and teacher bias toward female students stopped, girls would improve achievement in these courses, and be more inclined to pursue careers in these fields. Even though teachers try their best not to show gender bias, it does occur; however, it has been recommended that awareness should be raised about bias against women in STEM fields, girls and women in STEM areas need to focus more on attaining competence in their work, and institutions need to create more clear criteria for success and transparency (Hill, et al., 2010). Also, teachers can use various methods to stop gender bias and discrimination in their classrooms. These methods are: 1.) receive up-to-date training about gender bias in education as part of their pre-service teacher education (Stevens, 2015); 2.) be made aware of their gender-biased tendencies by requiring in-service training in schools (Chapman, n.d.), 3.) be provided with strategies for altering the behavior. Jones, Evans, Burns, and Campbell (2000) have provided teachers with a self-directed module aimed at reducing gender bias in the classroom. The module contains research on gender equity in the classroom, specific activities to reduce stereotypical thinking in students, and self-evaluation worksheets for teachers (Chapman, n.d.); 4.) combat gender bias in educational materials. They need to be inclusive, accurate, affirmative, representative, and integrated, weaving together the experiences, needs, and interests of both males and females. (Bailey, 1992). Some other strategies teachers can utilize to achieve equity in the classroom are: calling on girls as often as boys, encourage girls to be active learners, use gender-free language, give girls an equal amount of assistance and feedback, and help female students value themselves. Teachers, also, can use the following strategies to help female students with STEM-related courses. First, encourage girls to participate in extracurricular math and science activities. Secondly, organize a Girls' Club where female students can interact with mentors in the fields of math, science, technology, and engineering. Thirdly, provide opportunities for female students to teach lessons or tutor younger students or even parents in math, science, and technology. Fourth, insist that girls, as well as boys, learn to set up and use all electronic equipment. Lastly, provide female role models and guest speakers to speak with students (Sadker & Sadker, 1994). As Carol Bartz, CEO of Autodesk, an architectural and engineering design software company, stated,

“Girls deserve a choice. And choice comes from having knowledge and skills. They may get to college and think that math or computer science sounds interesting. But their path is set. If girls are not grounded in the fundamentals in elementary school and high school, they will be cut out of a career in technology. They won't have the skills, and it's very difficult to catch up at that point” (Bartz, n.d.).

For College Classrooms

A woman in college walks into a STEM-related classroom and realizes that she is among a small handful of women in the class, or possibly the only woman. This may lead her to feel uncomfortable, out-of-place, and a sense of not belonging, and compel her to search for more inclusive academic environments (Dasgupta, 2016). According to psychology researcher at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst, Nilanjana Dasgupta, there are five recommendations, based on research findings supported by the National Science Foundation, as to how schools and universities can make all students feel they belong, especially female students in STEM classes.

One, provide incoming female students more exposure to scientists, engineers, and innovators who are women. Second, create ways to enhance female students' exposure to technical women. This can be done by incorporating brief stories of the work of female scientists or engineers related to the content of the class, or invite female scientists or engineers to be guest speakers in their class. Third, organize a peer mentoring system where female students who are juniors or seniors in STEM majors serve as peer mentors to incoming women. The fourth recommendation involves work teams. Create teams with a critical mass of women and avoid teams where there's only one woman, or women are a tiny minority. The last recommendation is to remember that feelings of belonging are most at risk when women students are in developmental transition points. Having interventions targeting these transition points is key (Dasgupta, 2016).

When women feel that they “belong,” they feel a sense of comfort; however, if that feeling of belonging is not there, they look elsewhere for alternative sources. This goes in a college classroom. If a female student feels uncomfortable and a sense of not belonging, they will look for other courses where they do “fit in.” However, if colleges follow the recommendations of researchers, such as Ms. Dasgupta, then female students can follow their dreams of becoming one who works in technology or an engineer without feeling inferior to their peers.

For Parents

Parents have a huge influence on their daughters, and their words and “actions can have a major impact on girls’ aspirations, their sense of competence, and their interest in STEM fields” (Mosatche, et al., 2016). In the guidebook for parents, Breaking Through! Helping Girls Succeed in Science, Technology, Engineering, and Math (2016) by Harriet S Mosatche, Ph.D., Elizabeth K. Lawner, Susan Matloff-Nieves, they give suggestions as to how parents can help their daughters engage in STEM and break the gender barriers girls face. First, parents can make STEM a part of their daughter’s everyday life. They can give her an allowance so she can use math to calculate how much she needs to save and buy something she wants. Parents can also help their daughter explore engineering concepts by having her figure out how something works. Second, parents can expose their daughter to female role models or mentors in STEM fields. This can be done either in-person, in books, movies, or other media. Also, online biographies of real women in STEM are available on the NASA website and other sites. Third, parents can help their daughter to break through the gender bias found in toys and games by getting a chemistry set or a kit from such companies as Roominate Toys, which offers girls the opportunity to build houses and then wire rooms with lights and fans. Parents can also provide hands-on activities in STEM that are fun and educational. Another suggestion for parents is to take their daughter on trips to science museums, botanical gardens, zoos, planetariums, parks or beaches, where she can explore STEM. Fostering creative problem-solving, leadership, and teamwork skills, and encouraging their daughter’s sense of belonging in STEM are other ways in which parents can encourage their daughters to engage in STEM and break the gender gap (Mosatche, et al., 2016).

For Developing Countries

Females, today, in developing countries, still struggle with gender inequality and educational advancement. Even though the struggles continue, various individuals and organizations believe they can aid these women and change the gender prejudices toward females occurring in developing countries. One such person, who advocates for girls’ education, is Malala Yousafzai. Born in 1997 in northwest Pakistan, Malala, along with her father, had a passion for learning and going to school. In 2009, Malala and her father began receiving death threats from the Taliban for their opposition to Taliban efforts to restrict education and stop girls from going to school; however, Malala and her father continued speaking out. In 2011, she received Pakistan's first National Youth Peace Prize and was nominated by Archbishop Desmond Tutu for the International Children's Peace Prize. In response to her rising popularity and national recognition, Taliban leaders voted to kill her, and on October 9, 2012, on her way home from school, a masked gunman entered her school bus and shot Malala with a single bullet. Malala survived the attack. The Taliban's attempt to kill Malala received worldwide condemnation and led to protests across Pakistan. In the weeks after the attack, over 2 million people signed a right to education petition, and the National Assembly swiftly ratified Pakistan's first Right to Free and Compulsory Education Bill. Malala became a global advocate for the millions of girls being denied a formal education because of social, economic, legal and political factors, and in 2013, Malala and her father co-founded the Malala Fund to bring awareness to the social and economic impact of girls' education and to empower girls to raise their voices, to unlock their potential and to demand change. (Malala.org., n.d.). Today, at 19, Malala attends school and is the youngest appointed UN Messenger of Peace, which she has taken up the role, focusing specifically on girls' education.

One child, one teacher, one book, & one pen can change the world – Malala Yousafzai

Various organizations, also, advocate for girls’ education in developing countries. For instance, Project Nanhi Kali was initiated in 1996 by the K. C. Mahindra Education Trust (KCMET) with the aim of providing primary education to underprivileged girl children in India. Project Nanhi Kali’s belief is that educated women would not only contribute to the economy but also issues of population, and social evils like the dowry system and child marriage would reduce as more women are educated. Furthermore, Project Nanhi Kali provides educational material and social support that allows a girl child to access quality education, attend school with dignity, and reduces the chances of her dropping out.

A second organization, the Working to Advance STEM Education for African Women, i.e. WAAW Foundation, was founded in 2007 by Dr. Unoma Okorafo. As a lonely African female voice in Technology, Dr. Okorafo set out to create sustainable, long-lasting ways to support and educate African women in technology innovation. The WAAW Foundation recognizes that Female Education and Science and Technology Innovation are the two most crucial components to poverty alleviation and rapid development in Africa. Prejudices against the African woman and huge societal disadvantages in often male-dominated communities is vastly unexposed and requires a strong and compassionate voice. The WAAW Foundation believes that when girls are educated, societies are transformed, economies grow, health improves and everyone benefits.

Another organization, the United Nations Girls’ Education Initiative, i.e. UNGEI, was launched in 2000 by the UN Secretary-General Kofi Annan to assist developing countries in fulfilling their dedication toward providing universal education and promoting gender equality. Partnering with other international organizations, they work together to facilitate the coordination of girls’ education strategies at the country level, remove barriers toward schooling for girls, and re-enforce the importance of investing in girls’ future, for the benefit of the country.

Conclusion

Gender bias toward female education has been and still is, an ongoing worldwide problem. The gender prejudices that occur come from teachers, parents, and cultures, particularly when it involves STEM-related areas. From elementary school through college, and continuing into the workplace, females have felt a sense of not belonging and inferior to their male peers, mostly in science, technology, engineering, and math fields. However, researchers have suggested various solutions to this problem in which teachers and parents can adhere to, as well as organizations which help to terminate the gender gap occurring not only in the United States but around the world. On September 26, 2012, at the launch of Education First Initiative, Amina J. Mohammed, the U.N. Secretary-General stated,

Education empowers women to overcome discrimination. Girls and young women who are educated have a greater awareness of their rights, and greater confidence and freedom to make decisions that affect their lives, improve their health, and boost their work prospects - Amina Mohammed

Throughout the world, receiving a quality education is crucial in every individual’s life, no matter their gender. Furthermore, closing the gender gap is imperative for females’ aspirations and successes throughout their lives.

References

Ashton, E. (1983). Measures of play behavior: The influence of sex role stereotyped children’s books. Sex Roles, 9, 43-47.

Bailey, S. (1992) How schools shortchange girls: The AAUW Report. New York, NY: Marlowe & Company.

Boysen, G. A. (2013). Confronting math stereotypes in the classroom: Its effect on female college students' sexism and perceptions of confronters. Sex Roles, 69(5-6), 297-307. doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s11199-013-0287-y

Boysen, G. A., & Vogel, D. L. (2009). Bias in the classroom: Types, frequencies, and responses. Teaching of Psychology, 36, 12–17. doi:10.1080/00986280802529038.

Boysen, G. A., Vogel, D. L., Cope, M. A., & Hubbard, A. (2009). Incidents of bias in college classrooms: Instructor and student perceptions. Journal of Diversity in Higher Education, 2, 219–231. doi:10.1037/a0017538.

Catsambis, S. (1995). Gender, race, ethnicity, and science education in the middle grades. Journal of Research in Science Teaching, 32, 243– 257.

Chapman, A. (n.d.). Gender bias in education. Retrieved from http://www.edchange.org/multicultural/papers/genderbias.html

Dasgupta, N. (2016). 'Belonging' can help keep talented female students in STEM classes. Retrieved from https://www.nsf.gov/discoveries/disc_summ.jsp?cntn_id=189603

Delaware State Education Association. (2010). Gender bias. Retrieved from http://www.ccctc.k12.oh.us/Downloads/Gender%20Bias%20in%20the%20Classroom2.pdf

Eccles, J. S., Jacobs, J. E., & Harold, R. D. (1990). Gender role stereotypes, expectancy effects, and parents’ socialization of gender differences. Journal of Social Issues, 46, 183–201. doi:10.1111/j.1540-4560.1990.tb01929.x.

Fennema, E., Peterson, P. L., Carpenter, T. P., & Lubinski, C. A. (1990). Teachers’ attributions and beliefs about girls, boys, and mathematics. Educational Studies in Mathematics, 21, 55–69. doi:10.1007/BF00311015

Gunderson, E.A., Ramirez, G., Levine, S.C., Beilock, S.L. (2012). Sex roles 66: 153. doi:10.1007/s11199-011-9996-2

Hill, C., Corbett, C., & St. Rose, A. (2010). Why so few? Women in Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics. Retrieved from http://www.aauw.org/files/2013/02/Why-So-Few-Women-in-Science-Technology-Engineering-and-Mathematics.pdf

Hilliard, L. & Liben, L. (2010). Differing levels of gender salience in preschool classrooms: Effects on children’s gender attitudes and intergroup bias. Retrieved from http://napavalley.edu/people/cmasten/Documents/psych125/HilliardLiben2010.pdf

Intel. (2012). Women and the Web. Intel Corporation

Jones, K., Evans, C., Byrd, R., Campbell, K. (2000) Gender equity training and teaching behavior. Journal of Instructional Psychology, 27 (3), 173-178.

Jones, M.G., Howe, A., Rua, M. (1999). Gender differences in students’ experiences, interests, and attitudes toward science and scientists. Retrieved from http://www.weizmann.ac.il/st/blonder/sites/st.blonder/files/uploads/sohair.pdf

Kahle, J., & Lakes, M. (1983). The myth of equality in science classrooms. Journal of Research in Science Teaching, 20, 131– 140.

Kortenhaus, C. & Demarest, J. (1993). Gender role stereotyping in children’s literature: An update. Sex Roles, 28, 219-232.

Lynch, M. (2016). 3 signs of gender discrimination in the classroom you need to know. Retrieved from http://www.theedadvocate.org/3-signs-gender-discrimination-classroom-need-know/

Malala.org. (n.d.). Malala’s story. Retrieved from https://www.malala.org/malalas-story

Mohammed, A. (2012). Secretary-General's remarks on launch of education first initiative. Retrieved from https://www.un.org/sg/en/content/sg/statement/2012-09-26/secretary-generals-remarks-launch-education-first-initiative

Mosatche, H., Lawner, E., & Matloff-Nieves, S. (2016). Breaking Through! Helping Girls Succeed in Science, Technology, Engineering, and Math. Waco, TX: Prufrock Press

Mwaiko, N. (2017). Overcoming obstacles to educational access for Kenyan girls: A qualitative study. Journal of International Women's Studies, 18(2), 260-274. Retrieved from https://search.proquest.com/docview/1869850527?accountid=32521

National Center for Education Statistics. (2017). Most popular college degrees by gender. Retrieved from https://www.collegeatlas.org/top-degrees-by-gender.html

Ombati, V., & Mokua, O. (2012). Gender inequality in education in sub-Saharan Africa. Journal of Women's Entrepreneurship and Education, 114-136.

Project Nanhi Kali. (n.d.). About Project Nanhi Kali. Retrieved from http://www.nanhikali.org/who-we-are/index.aspx

Rampey, B.D., Dion, G.S., and Donahue, P.L. (2009). NAEP 2008 trends in academic progress (NCES 2009–479). National Center for Education Statistics, Institute of Education Sciences, U.S. Department of Education, Washington, D.C.

Saarthak. (n.d.). Women’s situation in India. Retrieved from http://www.saarthakindia.org/womens_situation_India.html

Sadker, D. and Sadker, M. (2014). Failing at fairness: How schools cheat girls, Touchstone, New York, N.Y.

Simmons, M. J. (1998). Gender bias and the junior high classroom. North Dakota Journal of Speech & Theatre, 11(1), 30-41.

Stevens, K., (2015). Gender bias in teacher interactions with students. Master of Education Program Theses. 90.

Tiedemann, J. (2000a). Gender-related beliefs of teachers in elementary school mathematics. Educational Studies in Mathematics, 41, 191–207.

Tiedemann, J. (2000b). Parents' gender stereotypes and teachers' beliefs as predictors of children's concept of their mathematical ability in elementary school. Journal of Educational Psychology, 92, 144–151. doi:10.1037/0022-0663.92.1.144.

Tiedemann, J. (2002). Teachers' gender stereotypes as determinants of teacher perceptions in elementary school mathematics. Educational Studies in Mathematics, 50, 49–62.

UNESCO. (2010). Adult literacy rates. Retrieved from http://www.unesco.org/education/tlsf/mods/theme_c/popups/mod12t01s01fig02.html

UNESCO. (2013). Doubling digital opportunities: Enhancing the inclusion of women and girls in the information society. Geneva, Switzerland: UNESCO

UNGEI. (n.d.). Girls' education plays a large part in global development. Retrieved from http://www.ungei.org/news/247_2165.html

WAAW. (2017). Why girls? Retrieved from http://waawfoundation.org/why-girls/

Warnecke, T. (2017). Social innovation, gender, and technology: Bridging the resource gap. 51(2), 305-314. doi:10.1080/00213624.2017.1320508

Weiss, D. (1991). The great divide. New York: Poseidon Press.

Weitzman, L. (1977). Sex role socialization in picture books for preschool children. American Journal of Sociology, 77, 1125-1150.

White, H. (1986). Damsels in distress: Dependency themes in fiction for children and adolescents. Adolescence, 21, 251-256.

Witt, S.D. (2001). The Influence of school and reading materials on children’s gender role socialization: An overview of literature forthcoming, curriculum and teaching. Retrieved from http://gozips.uakron.edu/~susan8/school.htm

Yee, D. K., & Eccles, J. S. (1988). Parent perceptions and attributions for children's math achievement. Sex Roles, 19, 317–333. doi:10.1007/BF00289840.