Peer Review Worksheet

Running Head: INFALLIBILITY Page 0

The Infallibility of the Bible

David C. Dulaney

Advanced Research Project Draft – LIB495

Justin Brumit

1 June 2017

The Infallibility of the Bible

The focus of this paper centers on the infallibility of the Bible. The key word here is infallible. What does this word mean? If you were to look up in a dictionary, you would find that the word is defined as being incapable of error (Merriam-Webster, 2017). With that definition associated to the Bible, one might question how a book written over a span of 1400 years by multiple authors in two different languages could be free of any errors (Sirman, 2011). Even more perplexing is how the Bible tells a clear and comprehensive message that has remained applicable to generations of people regardless of the era in which they lived. In terms of application, the Bible has continued to inspire, instruct, and empower its readers through its time honored message. Having such a profound impact on the lives of its readers, one has to question why the Bible is different than other books written over the course of history. For this, one has to ask how more than 40 authors complemented one another through their writing’s. Were the authors inspired by God, or are their writings the result of divine intervention? In all respects, there had to be something greater than the author’s own intuition that would have led them to write the Bible. If God in-fact was the originator of the penning of the Bible, one has to question why there is so much discourse over the infallibility of the Bible by those in the religious community. How could the Bible, which is in all respects is the Word of God, be questioned for its validity? Interestingly, the same people who believe the Bible to be the Word of God differ in their opinion as to the infallibility of the Bible. What could be the reason behind this difference in opinion? By delving into the history of the Bible, I believe the answer to its infallibility can be uncovered. Although I acknowledge there is growing uncertainty as to the infallibility of the Bible, I claim that the various translations of the Bible over the years have directly impacted the intended message, meaning, and context of the original books. Upon a review of the Bible, it can be noted that the 66 books seamlessly blend together to guide, inspire, and educate all who approach it with an open heart and mind. If we are to find the answer to the Bible’s infallibility, it is imperative to conduct a comprehensive review of its history. Over the course of this paper, I will be discussing the origins of the Bible, the history of the written Bible, the Protestant Reformation, the Enlightenment, differing interpretations of the Bible, and finally discuss what I believe is the answer to determining its infallibility. As with all problems, it is necessary to start at the beginning. For this, I will be discussing the origins of the Bible.

Origins of the Bible

As previously stated, the Bible is a collection of 66 books which was written over a 1400 year period. In the broadest sense, the Bible is a historical document which stands to explain creation of the universe as well as humankind’s reason for existence. The Bible in itself can be broken down into two distinct parts. These two parts are the Old and New Testaments. As a collection of 39 books, the Old Testament provides the groundwork which records history up to the coming of the foretold Messiah. Beginning the Old Testament, the book of Genesis opens by discussing the origins of humankind, and the need for a relationship with God. From there, the Old Testament delves into the chronological accounts of the patriarchs (i.e. Abraham, Isaac, Moses, Saul, David, and Solomon) and the prophets whose lives were interconnected through their devotion to God. Additionally, it is in the Old Testament where the historical accounts of wars, betrayals, and personal conflicts are documented primarily by those who experienced them first-hand. For instance, the book of Joshua was written by Joshua (Peach, n.d.). On the other hand, there is the book of Genesis which was written by Moses (Peach, n.d.). Although Moses does not show up in the Bible until the book of Exodus (the second book of the Bible), he is believed to have written the book of Genesis (Peach, n.d.). Following the Old Testament is the New Testament. Comprised of 27 books, the New Testament opens with the gospels. The first of these is the book of Matthew. In the book of Matthew, the coming Messiah arrives and the story of Jesus unfolds. In line with the book of Matthew, the following three gospels (Mark, Luke, and John) tell a similar story as was documented by Matthew. The remainder of the New Testament follows the historical book of Acts, the epistles, and ends with the book of Revelation. Although the majority of the New Testament takes place following the death of Jesus, the primary focus is on Jesus’s return and the personal relationship believers need to have with God.

When we look at the Bible, it becomes evident that there is a correlation between the Old and New Testaments. This correlation is three fold. The first is that there is common theme throughout the Bible that the God desires to have a personal relationship with humankind. Second, the prophecies about the forthcoming Messiah in the Old Testament were fulfilled with the arrival of Jesus in the New Testament. For example, in Micah 5:2, it was prophesied that the Messiah would be born in Bethlehem (Fairchild, 2017). As you read the New Testament, you find out that this was fulfilled as noted by Matthew 1:20 and Galatians 4:4 (Fairchild, 2017). Another example comes from Isaiah 7:14, where it was prophesied that the Messiah would be born of a virgin (Fairchild, 2017). Just as with the first example, this would be fulfilled in the New Testament as noted in Matthew 1:22-23 and Luke 1:26-31 (Fairchild, 2017). Even the lineage that Jesus hails from is also prophesied in the Old Testament (Fairchild, 2017). As noted, it was prophesied that he would be a descendent of Abraham (Genesis 12:3 and Genesis 22:18), Isaac (Genesis 17:19 and Genesis 21:12), Jacob (Numbers 24:17), the tribe of Judah (Genesis 49:10), and be heir to King David’s throne (2 Samuel 7:12-13 and Isaiah 9:7) (Fairchild, 2017). These prophesies would be fulfilled as noted in the books of Matthew, Luke, Romans, and Hebrews (Fairchild, 2017). Finally, even the specifics about his death would be fulfilled in the New Testament as they were stated in the Old Testament (Fairchild, 2017). The third and final way the Old and New Testament’s correlate to one another stems from their cohesiveness. As noted previously, the 66 books were penned by over 40 authors over a 1400 year period. Even though the authors never collaborated, their accounts follow suit and tell a cohesive message that still resonates in today’s modern age.

The Written Bible

Looking back on history, the Bible did not begin as the mass produced book for the average person as it is today. In fact, it was not until the third century that it began to take on that title (Levenson, 2014). Unlike today where everyone can own a translated copy of the Bible, early believers were not privy to the text (Levenson, 2014). In fact, only a small group of scribes had access to the original texts (Levenson, 2014). Instead of practicing religion through the Bible, people pursued religion by going to the temple, performing sacrifices and participating in traditional customs (Levenson, 2014). It would not be until fourth century A.D. that a translated revision would be produced from the original texts (Ford, 2003). As history reveals, St Jerome would translate the Greek and Hebrew texts into Latin (Ford, 2003). His translation, titled the Vulgate, would become the cornerstone of the Roman Catholic Church (Ford, 2003). Important to note, there were other Latin translations circulating at the time. However, the Vulgate would be the most accurate translation closest to the original text that existed (Ford, 2003).

As the Middle-Ages came to fruition, the Vulgate would become the sole source from which copies of the Bible would be scribed (Ford, 2003). As to the scribing process, it was a precise art and required a high level of devotion (Ford, 2003). Those selected to perform the daunting task of scribing adhered to strict rules and would face harsh punishments if they were lackadaisical in their tasks (Ford, 2003). During that time, the Bible was primarily accessible by those assigned to the Church (Ford, 2003). However, as time went by, we find that there was a shift in who had access to the Bible. The reason for this stems around literacy and learning. Where literacy and learning was primarily assigned to the monks, it was now becoming more prevalent outside the Church (Ford, 2003). By the year 1100, access to the Bible would be afforded to the masses (Ford, 2003). With the Bible in the hands of the secular community, it began become necessary to improve its readability. For this, Bibles became smaller in size, a sequential order of the books was instituted, reference materials were added to assist with translating the Hebrew names, and the chapters within the books were numbered (Ford, 2003). By 1270 A.D. the Bible was taking on a new and enhanced format (Ford, 2003). As much as this should have been seen in a positive light, it was in-fact discomforting to the Church that the Bible was being changed from its original form. Case in point, the Church followed the Vulgate translation of the Bible. With other versions of the Bible being published, there was a fear that their authority would be questioned. One person in particular that challenged the Church’s stance was John Wycliffe. John Wycliffe was a renowned Catholic priest who graduated Oxford in 1372 (Cangelosi, 2014). He believed that the leaders in the Church were using their positions to better themselves (Cangelosi, 2014). Additionally, he believed that the Bible was the ultimate authority, and that people should not rely on the self-serving teachings of the popes and clerics (Cavendish, 2015). With this, he spoke out against the Church and wound up being banned from his teaching position 1382 (Mocanu, 2015). With his belief that each man was individually accountable to God, he wanted to ensure that everyone had a Bible translated in his/her own native language (Cangelois, 2014). From this, the Wycliffe Bible would come to be published. As it was translated into varying languages, the Wycliffe Bible did not follow a word-for-word translation of the Vulgate (Ng, 2001). Instead, it focused on providing a translation that was more focused on meaning than a direct translation (Ng, 2001). Being that the Church banned translating and reading vernacular scripture, they stuck to their view that the Vulgate was the only legitimate text and the Wycliffe version was heresy (Ng, 2001). Unlike the Wycliffe Bible that was a translation of a Latin translation, the Tyndale was translated from the original Hebrew and Greek (Ng, 2001). Like Wycliffe, William Tyndale did not see eye to eye with the Church. His view was that there should not be a difference between the clergy and the average man in terms of spiritual knowledge (Ng, 2001). By making the scriptures accessible to the average man, he stated the clergy would not be in a position to cast judgement based on their supposed superior intellect (Ng, 2001). Instead, it should be God who passes said judgement. Like Wycliffe, Tyndale graduated Oxford and took on the priestly profession (Patterson, 1997). Having studied Greek, he sought permission to translate the original texts of the Bible into English (Patterson, 1997). Unfortunately, he was denied his request by the bishop of London, Cuthbert Tunstall (Patterson, 1997). Following, he went into exile where he began publishing his translations of the New Testament (Patterson, 1997). Over the course of nine years, Tyndale successfully published a revised New Testament as well as the first five books of the Old Testament (Patterson, 1997). As history reveals, his books were condemned, banned, and burned in England (Patterson, 1997). Following, his life came to an end in 1536 (Patterson, 1997). Having been guilty of heresy, he was strangled and burned him at the stake in Brussels (Patterson, 1997). His published works were not completed in vain. In fact, after his death it was discovered that he had translated even more books in the Old Testament (Patterson, 1997). Surprisingly, even though his translations were thought to have been destroyed, his translations made their way into the Matthew’s Bible (Patterson, 1997). It is from here that his work has continued to make its way into many more versions of the Bible. From the Great Bible of 1539 which was mandated to be in every English parish church to the Geneva Bible of 1560, we find that although William Tyndale was executed his work has continued to live on (Patterson, 1997). Unbeknownst at the time of their penning, the works of John Wycliffe and William Tyndale would be the catalysts that would help ignite the Protestant Reformation.

John Wycliffe (c.1330-84)

The first printed English New Testament, tr. by William Tyndale

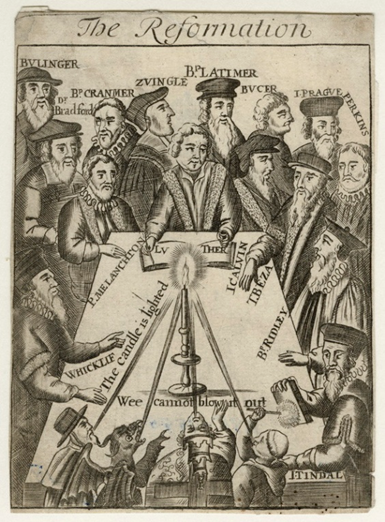

The Protestant Reformation

The 14th century brought about a significant change in the way people viewed the Church. Up to that point, the clergy and papacy were benefiting from their respected positions and their connections with the Roman Curia (Mocanu, 2015). It would not be long until their lavish lifestyle and self-proclaimed authority would begin to be questioned by the general populace. As previously discussed, John Wycliffe and William Tyndale saw through this façade and took it upon themselves to challenge the authority of the Church. With the penning of their biblical translations, they created a shift in mindset whereas the scriptures were not the sole property of the Church. Additionally, they opened the public’s eyes to the knowledge that the Scriptures were source of authority and not the Church. In line with Wycliffe and Tyndale, there was another person who had significant role in the reform movement. This person was none other than Martin Luther. Born in 1483, Luther began his education at the University of Erfurt (Heal, 2017). After being awarded his Master’s degree in 1505, he moved on to take a position in an Augustinian monastery (Heal, 2017). Over the course of the next two years, he progressed through the clergy wound up taking up priesthood in the year 1507 (Heal, 2017). After moving to Wittenberg, he completed his doctorates (Heal, 2017). Following, he began teaching at the university and served as pastor at a local parish (Heal, 2017). Luther’s views shifted after Leo X, pope of Rome, pushed for the sale of indulgences to offset the cost of completing St Peters at Rome (Heffer, 2017). In the simplest of terms, the pope was promising people that they would serve less time in purgatory if they paid into the coffer (Heffer, 2017). In Luther’s opinion, nobody could buy their way into heaven. Instead, he believed that it was faith in God that assured someone would go to heaven. For this, he wrote his Ninety-Five Theses. In his Ninety-Five Theses, Luther challenged the indulgences of the Church. In his words, he stated that the pope should pay for St Peters and not the “poor believers” (Heffer, 2017). After his theses was posted in public view, it was taken into neighboring German cities (Heal, 2017). Even more, the Archbishop Albrecht of Brandenburg sent a copy of the document to Rome where it was reprinted and sent out across much of Europe (Heffer, 2017). Although the Ninety-Five Theses was not a direct attack on the Church, it did shed light on two controversial issues stemming from the Church. First off, it argued against the idea that people could pay for their sins (Heal, 2017). Secondly, it questioned the pope’s claim that he had authority over the deceased (Heal, 2017). In a nutshell, Luther Ninety-Five Theses challenged the Church for their exploitation of the poor and also called into question the authority of the pope. Following the publishing of his Ninety-Five Theses, Luther continued to stand behind his beliefs even though he received much resistance from the leaders in the Church (Heffer, 2017). In the years that followed, Luther would go on to write additional publications further edifying the stance that eternal life could be awarded through a belief in God provided salvation and the Church was not the ultimate authority (Heffer, 2017). Because his teachings challenged the authority of both the pope and the Church, he wound up being excommunicated by Leo X. Following in the year 1521, he was summoned to stand before Emperor Charles V at the Imperial Diet of Worms to retract all that he had published (Heal, 2017). To their dismay, he refused to recant what he wrote and in turn challenged the very assembly that was questioning his works. During that hearing, he challenged the assembly to identify where his works contradicted the scriptures. Until they could do so, he stated that he would be bound to the very scriptures that he had quoted, and that he would not veer from his understanding of the Word of God (Heal, 2017). Following the hearing, Charles V declared Luther an outlaw and placed him under imperial ban. As for the rest of his life, he spent it at the Wartburg Castle in Eisenach. It was here that he would continue his writing and publish a German translation of the Bible. As history reveals, his actions were not in vain. For it was his steadfast determination and provocative insight that Martin Luther would be coined the man who awakened a nation and gave start to the Protestant Reformation (Heal, 2017). Additionally, it would be his German translation of the Bible that would become used in England, Scotland, and other protestant countries (Heffer, 2017). If we look back, it becomes evident that Martin Luther, John Wycliffe & William Tyndale were instrumental in the beginnings of the Protestant Reformation. Had it not been for those three gentleman and others like them, the authority of the Church might never have been questioned, and the Bible of today might have ceased to exist. Similar to the beginning of the Protestant Reformation, the Age of Enlightenment ushered in an era where people yearned to discover the truth.

William Tyndale by Unknown artist, late 16th Century

The Enlightenment

The Age of Enlightenment was a phenomenal time of discovery that occurred during the 18th and early 19th centuries. During this time period, history reveals that there was a cultural shift whereas people were driven to understand the natural world around them (Bowles, 2012). This new modern mindset was far different from preceding years where people held to more religious ideologies and where the church was the primary source of guidance (Bowles, 2012). Moving into the Age of Enlightenment, new discoveries were began being made in relation to the natural world. As such, there came a desire to associate the scriptures to the “natural world”. This new way of studying the scriptures was far different than the previous years. As discussed, the Protestant Reformation ushered in era where the focus was on the literal meaning of the scriptures. For this, we saw the penning of the Wycliffe, Tyndale, and Luther bibles. Additionally, we bared witness to the conflicts that arose as the authority of the Church was challenged when everyday people applied the scriptures in their most literal sense. Shifting back to the Age of Enlightenment, discoveries about the natural world were causing people to question the literal meanings of the scriptures. It is for this reason that people began searching for a way to apply the scriptures rather take them at face value. Out of this need to make sense of it all came four ways of approaching the scriptures. These included deism, religion of the heart, fideism, and atheism (Bristow, 2011). Deism was the belief that the universe was created and governed by a higher power (Bristow, 2011). Through the deist’s approach to the scriptures, the various miracles written about in the Bible were contradictory to the natural workings of the Universe (Bristow, 2011). For this reason, they chose to reject the teachings in the Bible centered on miraculous outcomes (Bristow, 2011). Additionally, they refuted the divinity of Jesus and the miracles he performed as documented in the scriptures (Bristow, 2011). On the other hand, they did believe in a higher power. Their view of a higher power stemmed from their understanding that there was a natural order to the universe (Bristow, 2011). Next, religion of the heart followed a more personal approach to God. Unlike deism that saw God as an outside entity who remained clear of his creation, those who followed the “religion of the heart” saw God in everything around them and felt personally in touch with the benevolent creator (Bristow, 2011). Following, there were others who followed fideism. In regards to fideism, there was a belief that a person’s faith could not be challenged by reason (Bristow, 2011). In other words, even though outside reasoning may oppose an individual’s faith, it does not have any bearings as to whether an individual’s faith is wrong (Bristow, 2011). Finally, the Age of Enlightenment saw the beginnings of atheism. Atheism is centered on the ideal that the natural trumps the supernatural (Bristow, 2011). Within that, their belief followed a more natural approach to understanding the universe and the world around them (Bristow, 2011). In retrospect, the Age of Enlightenment brought about a change in the way people related to the scriptures. Instead of deciphering the scriptures based on their literal meanings, people were beginning to identify more natural ways of applying them to their lives. Just like the approach to the scriptures has changed over the years, so too has the ways in which the Bible has become interpreted. Although there is no single way of interpreting the Bible, one thing is for certain. This is a person’s interpretation of the Bible will have a bearing on whether or not they will believe the book to be the infallible Word of God.

Differing Interpretations

Looking back on history, the Bible has become the center of many discussions. I believe the reason for this stems around the varied ways in which it can be interpreted. For the sake of this discussion, I would like to hone in on four ways in which the Bible has become interpreted over the years. These four interpretations include that the Bible is the infallible Word of God, the Bible is a farce, the Bible is a summary report of God’s works, and lastly that the Bible is just another idea about how the universe was created. As noted, the first way the Bible has become interpreted is that it is the infallible Word of God. If this interpretation is accurate, then it would insinuate that the 66 books within the Bible contained no errors. Additionally, it would mean that the Bible of today has remained true to its original Greek and Hebrew form. As such, it could be considered a timeless source of truth (Perry, 2016). Following this interpretation, one could view the Bible as a source of spiritual awakening. Even more, it would provide justification for the reader to pursue a relationship with the God that created the Universe. Moving on, the second way of interpreting the Bible is that it is a farce (Eichenwald, 2015). If one follows this interpretation, they would reject any notion that the Bible was infallible. Those who have followed this train of thought often state that the Bible contains contradicting witness accounts, misreported facts, and illogical stories (Eichenwald, 2015). Next, there is the theme that the Bible should be viewed as a report of the Word of God (Warner, 2012). With this interpretation of the scriptures, the texts would yet again fail to be infallible. Instead, the scriptures would follow more to be an authoritative source that one could apply to their lives (Warner, 2012). Finally, there is the interpretation that the Bible is a historical record of how the Universe was created (Wisse, 2000). By interpreting the Bible in this way, the story of creation would be seen as factual (Wisse, 2000). However, just as with the two preceding interpretations, the infallibility of the Bible would be held in question (Wisse, 2000).

Uncovering The Bible’s Infallibility

In order to discover the answer to this question, one has to conduct a thorough review of the Bible’s existence. As I discussed, the books of the Bible were written over the course of 1400 years. Following, history would reveal that the books of the Bible were translated from their original Greek and Hebrew format into Latin (the Vulgate) by St Jerome in the year 400 A.D (Ford, 2003). Years later, John Wycliffe would take the Vulgate and create his own simplified Latin reproduction to give to the masses (Cangelosi, 2014). 100 years later, William Tyndale would again revisit the original Greek and Hebrew texts and publish his own translation of the Bible into English (Patterson, 1997). Finally, it would be Martin Luther who would publish a German Bible that would eventually make its way into the Protestant masses across Europe (Heffer, 2017). As we look back on the efforts of those individuals, it becomes clear that the books of the Bible have been translated multiple times over the course of history. Personally, I believe that the original Greek and Hebrew books of the Bible were the infallible Word of God. Whether someone agrees with that statement or not is not the case here. However, what matters is whether the act of translating the Bible has taken away from the Bible and in-turn impacted the infallibility of the Bible.

Personally, I have seen how translations between different languages unintentionally distort the meanings of words and phrases. Having studied six different languages (English, German, Latin, Mandarin Chinese, Korean, Tagalog, and Japanese), I know there are rules that one has to adhere to when writing and speaking any respective language. These rules inherently have a bearing on the context and meaning of the messages being presented. If the rules are not followed to the “T”, the intended message can unwittingly become distorted from what was originally intended. I associate this to playing the game “Telephone”. For those of you who have not played the game, one person starts the game by whispering a message into the first person’s ear. Following, the message gets passed from one person to the next until the last person in line recites what they were told by the person preceding them. In almost all cases, the message repeated is not the same as the original message. Similar to this, the process of translating the Bible has experienced the same outcome. As discussed, the first Bible was written by St Jerome. As history recalls, his version was not absolute. In fact, William Tyndale’s version was actually more thorough in his (Ng, 2001).

As history has revealed, there has been an ongoing desire to create a Biblical translation closer to its original form. Case in point, long after Wyclife, Tyndale, and Luther wrote their Bibles, the King James Version came to fruition. Published back in the early nineteenth century, the KJV is still being used in churches today (Perry, 2016). Regardless of the translation being referenced, one thing remains constant. This is that the original meaning of the Biblical texts needs to be preserved. As we look back on the ancient Greek and Hebrew texts, it is important to note that individual words could have different meanings (Culbertson, 1992). All in all, there were four different meanings a word could take on dependent on its category (Culbertson, 1992). The categories included literal, allusive, homiletical and mystical (Culbertson, 1992). Without knowing the specific category of a word, the true meaning would wind up lost in translation (Culbertson, 1992). If that happens, it only begs to reason that the translation is not the same as the original. In the case of the Bible, it would cause its infallibility to be questioned.

Over the course of history, the overall consensus of the Bible being the infallible word of God has become less conceptualized. Up until the Age of Enlightenment, the belief in the historical truthfulness of biblical texts were shared by most Christians (Johnson, 2009). But, as we entered the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, world exploration would drive the discovery of new peoples and cultures that did not exist in the Bible (Johnson, 2009). Because of these new discoveries, people began to question both their beliefs and the infallibility of the Bible (Johnson, 2009). Although this is not the sole reason why the Bible has taken a less than noteworthy stature, it does highlight one of the leading reasons why the Bible has become criticized. In my opinion, I do not believe mankind woke up one day and decided to disregard the Bible as being infallible. Instead, I think there were cultural changes that gradually led humankind to question what they had blindly accepted as truth.

Through it all, I believe the answer to getting back to where we need to be is two-fold. First and foremost, humankind has continually tried to find ways to apply the Bible to their lives (Marshall, 2007). Being that the Bible is centuries old, there will always be a need to find applicable ways to apply it to everyday life (Marshall, 2007). If we were able to get back to its original context, we might find the answer of its infallibility. Second, I have to suspect that much of what was originally stated in the Bible has lost its meaning due to incessant translating. I fear that this has primarily occurred due to our desire to have the Bible current with the times. By creating new versions, it only begs to reason that the Bible’s original message has gotten distorted. If the original books of the Bible are in-fact infallible, it would only be wise to return to the original texts and ensure that Bible we are reading is a direct translation of the original books.

Conclusion

Although I acknowledge the uncertainty of its infallibility, I claim that Biblical translation has directly impacted the intended message, meaning, and context of the original works. In this discussion, I provided a review of the Bible’s origins as well as a review of the early history of Biblical translations. Following, I discussed the Bible as it related to the Protestant Reformation and the Age of Enlightenment. Next, I discussed the four ways in which the Bible can be interpreted. Finally, I provided an in-depth discussion on what I feel needs to be accomplished in order to restore the legitimacy of the Bible. As with everything in history, we have no way of going back in time and witnessing what happened firsthand. For this, we have to ensure that our sources are accurate. As we continue to modernize, materialize, and gain a broader understanding of the universe, it is imperative to not lose anything in translation. Regardless of one’s opinion on its infallibility, the Bible remains a beacon of moral sanctity for all who choose to follow its teachings.

References

Bible. (1871). The first printed English New Testament, tr. by William Tyndale, photo-

lithographed from the unique fragment, now in the Grenville collection, British museum, ed.

by Edward Arber. Retrieved from https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=uc1.311750

21987535 ;view= 1up;seq=11

Bowles, M. & Kaplan, B. (2012). Science and culture throughout history. San Diego,

California: Bridgepoint Education, Inc.

Bristow, W. (2011). "Enlightenment", The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, Edward N.

Zalta (ed.). Retrieved from https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/sum2011/entries/

enlightenment

Cangelosi, C. (2014). The Mouth of the Morningstar: John Wycliffe's Preaching and the

Protestant Reformation. Puritan Reformed Journal, 6(2), 187. Retrieved from http://eds.a.eb

scohost.com.proxy-library.ashford.edu/eds/pdfviewer/pdfviewer?vid=1&sid=93783786-

2708-4a8a-a2fd-064a1ba6538c%40sessionmgr4008&hid=4208

Cavendish, R. (2015). John Wycliffe condemned as a heretic. History Today, 65(5), 8. Retrieved

from http://eds.a.ebscohost.com.proxy-library.ashford.edu/eds/detail/detail?vid=1&sid=a5

fd26f1-bf39-4164-aacd-5731c4cffa13%40sessionmgr4009&hid=4208&bdata=JnNp

dGU9ZWRzLWxpdmU%3d#AN=102221395&db=a9h

Culbertson, P. (1992). Known, knower, and knowing: The authority of scripture in the Episcopal

Church. Anglican Theological Review, 74(2), 144. Retrieved from: http://eds.b.ebscohost.

com.proxy-library.ashford.edu/eds/detail/detail?vid=34&sid=d1409ddf-1a00-453e-81b2-

98c779f4bc2f%40sessionmgr104&hid=121&bdata=JnNpdGU9ZWRzLWxpdmU%3d#db

=a9h&AN=9604166759

Eichenwald, K. (2015). The Bible: So Misunderstood It's a Sin. Newsweek Global, 164(1), 24-

41. Retrieved from: http://eds.a.ebscohost.com.proxy-library.ashford.edu/eds/detail/detail?

vid=4&sid=c7c8e910-ab75-4bb1-a1c9-83c6fdd71ef6%40sessionmgr4007&hid=4102&bd

ata=JnNpdGU9ZWRzLWxpdmU%3d#AN=100179236&db=a9h

Fairchild, M. (2017). Prophecies fulfilled by Jesus. Retrieved May 28, 2017, from

https://www.thoughtco.com/prophecies-of-jesus-fulfilled-700159

Ford, E. (2003). The Book: a history of the Bible. Christianity and literature, (2), 251.

Retrieved from http://journals.sagepub.com.proxy-library.ashford.edu/doi/pdf/10.1177

/014833310305200212

Heal, B. (2017). Martin Luther and the German Reformation. History Today, 67(3), 28-36.

Retrieved from http://eds.b.ebscohost.com.proxy-library.ashford.edu/eds/det

ail/detail?vid=1&sid=3a7db1e6-6e4f-4de1-945b-e0397129cd74%40sessionmgr120&hid=

119&bdata=JnNpdGU9ZWRzLWxpdmU%3d#AN=121659765&db=a9h

Heffer, S. (2017). The shout that awakened nations: Martin Luther, the Reformation--and the

birth of the modern world. New Statesman, (5351). 24. Retrieved from

http://eds.a.ebscohost.com.proxy-library.ashford.edu/eds/detail/detail?vid=1&sid=9a8c447a-

3f91-4e3d-864c-6e4f9c1786a8%40sessionmgr4006&hid=4111&bdata=JnNpdGU9ZW

RzLWxpdmU%3d#AN=edsgcl.484155945&db=edsglr

Infallible [Def. 1]. (n.d.). Merriam-Webster Online. In Merriam-Webster. Retrieved February 5,

2017, from http://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/citation

John Wycliffe (c.1330-84) (engraving) (b/w photo). (2014). Bridgeman Images: The Bridgeman

Art Library. Retrieved from http://eds.a.ebscohost.com.proxy-library.ashford.edu/eds/

detail/detail?vid=1&sid=913fd278-3051-47df-b9c3-8ed3355efa6f%40sessionmgr4007&hid

=4111&bdata =JnNpdGU9 ZWRzLWxpdmU%3d#AN=edscra.16176047&db=edscra

Johnson, L. T. (2009). How is the Bible true? Let me count the ways. Commonweal, (10), 12.

Retrieved from: http://eds.b.ebscohost.com.proxy-library.ashford.edu/eds/detail/de

tail?vid=5& sid=e41acf64-3811-4547-bfd2-9e6d3ffb5ffd%40sessionmgr103&hid=12

1&bdata=JnNpdGU9ZWRzLWxpdmU%3d#AN=edsgcl.201087409&db=edsglr

Levenson, J. D. (2014). Missing the text. Commentary, (6), 70. Retrieved from

http://eds.b.ebscohost.com.proxy-library.ashford.edu/eds/pdfviewer/pdfviewer?

vid=1&sid=ac1c6406-39da-466a-a68e-619e2ae2841e%40sessionmgr103&hid=114

Marshall, C. (2007). Re-engaging with the Bible in a postmodern world. Stimulus: The New

Zealand Journal of Christian Thought & Practice 15(1). 5-16. Retrieved from:

http://eds.b.ebscohost.com.proxy-library.ashford.edu/eds/pdfviewer/pdfviewer?

vid=28&sid=d1409ddf-1a00-453e-81b2-98c779f4bc2f%40sessionmgr104&hid=121

Mocanu, G. (2015). John Wycliffe and the Lollards: Precursors of the Protestant Reform. Revista

teologica, (1), 154-170. Retrieved from http://eds.a.ebscohost.com.proxy-library.ashford.

edu/eds/pdfviewer/pdfviewer?vid=4&sid=31c568d3-90e4-49f3-80f4-

1a35f8e0f5b2%40sessionmgr4008&hid=4111

Ng, S. F. (2001). Translation, interpretation, and heresy : the Wycliffite Bible, Tyndale's Bible,

and the contested origin. Studies In Philology, (3), 315. Retrieved from http://eds.a.ebscoh

ost.com.proxy-library.ashford.edu/eds/pdfviewer/pdfviewer?vid=1&sid=89095e6c-46e2-

4101-802f-d0ca1e9ce6eb%40sessionmgr4010&hid=4205

Patterson, W. B. (1997). Englishing the scriptures. Sewanee Review, 105(1), 105. Retrieved

from http://eds.a.ebscohost.com.proxy-library.ashford.edu/eds/detail/detail?vid=2&sid=68e

6c30b-9797-4c78-96ac-46943ff11551%40sessionmgr4007&hid=4208&bdata=Jn

NpdGU9ZW RzLWxpdmU%3d#AN=9703171689&db=a9h

Peach, D. (n.d.). Books of the Bible: Complete list with authors. Retrieved May 28, 2017, from

http://www.whatchristianswanttoknow.com/books-of-the-bible-complete-list-with-authors/

Perry, S. (2016). Scripture, time and authority among early disciples of Christ. Church History,

85(4), 762. Doi: 10.1017/S0009640716000780. Retrieved from: http://eds.a.ebscohost.com

.proxy-library.ashford.edu/eds/pdfviewer/pdfviewer?vid=2&sid=c7c8e910-ab75-4bb1-a1c9-

83c6fdd71ef6%40sessionmgr4007&hid=4102

Sirman, W. J. (2011). A general overview of religious beliefs. Culture & Religion Review

Journal, 2011(2), 69-92. Retrieved from http://eds.a.ebscohost.com.proxy-

library.ashford.edu/eds/pdfviewer/pdfviewer?vid=7&sid=57a95872-55f7-41fd-88cf-

8439279ba478%40sessionmgr4009&hid=4102

Warner, M. (2012). Reading the Bible "as the report of the Word of God": The Case of T. S.

Eliot. Christianity & Literature, 61(4), 543-564. Retrieved from: http://eds.b.ebscoho

st.com.proxy-library.ashford.edu/eds/pdfviewer/pdfviewer?vid=23&sid=d1409ddf-1a00-

453e-81b2-98c779f4bc2f%40sessionmgr104&hid=121

William Tyndale by Unknown artist, late 16th century. (2014). National Portrait Gallery Image

Collection. Retrieved from http://eds.b.ebscohost.com.proxy-library.ashford.edu/eds/detail/

detail?vid=5&sid=7e77e578-da78-4ad1-b9c7-38716a4d1803%40sessionmgr102&hid=119&

bdata=JnNpdGU9ZWRzLWxpdmU%3d#AN=edscra.18690457&db=edscra

Wisse, M. (2000). The Meaning of the Authority of the Bible. Religious Studies, 36(4), 473-487.

Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/20008314