respond

3 Concepts and Theory of Local Economic Development

The predominant definition that has undergirded traditional economic development practice is increasingly recognized as insufficient. Even in the most prosperous economies, time and again it has been shown that the major economic development problems cannot be solved using this definition. Indeed, the legacies of this definition are global warming and growing inequality. These two trends are at the forefront of contemporary U.S. concerns precisely because inadequate attention has been paid to the distributional aspects and environmental impacts of economic growth in the past.

Defining Local Economic Development

What drives the diffusion of the phases of economic development discussed in Chapter 2 is the definition of economic development upon which they are based. The traditional and most widely referenced definition of economic development has long been that of wealth creation. This definition is the driver of the first and second economic development phases exclusively and the entrepreneurial strategy of the third phase. Increasing the tax base and creating jobs are the fundamental objectives of this definition that equates economic development with economic growth (Fitzgerald and Leigh, 2002; Malizia and Feser, 1999). There is nothing wrong with creating wealth and jobs and increasing the tax base. But it is a great mistake to equate economic growth with economic development. The blind pursuit of economic growth can destroy the foundation for economic development. For example, if an economy’s growth is based on an exhaustible natural resource supply (e.g., timber, seafood, coal), then it will eventually come to a halt. The workers will be unemployed, and, without proper attention to the education and skill development of the labor force or to the development of a more diversified industry structure, the community can enter a death spiral. The same scenario applies in the case of one-industry or one-factory towns. Shifts in the global economy or in technology can negate the community’s desirability to its sole industry. The industry may move, or its owners may exit the industry and the town, taking their capital with them. These are the simplest of examples, and it should be understood that a town with more than one industry but with a narrow industrial base can be just as vulnerable.

At least in the public and nonprofit sectors, blind pursuit of economic growth simply to create more wealth and jobs needs to be rejected if it is likely to lead to increases in income inequality, irrevocably harm the environment, or worsen the plight of marginalized groups. Economic growth that is based on exploitation of workers with few or no alternative employment options not only is unethical but also may violate fair labor standards and other laws. Growing inequality can ultimately destabilize the economy and society and result in clashes between the haves and have-nots. Such clashes can result in community-destroying violence.

The sources of growing inequality are multiple but often reflect a failure in economic development leadership—for example, a failure to provide a skilled labor force that is attractive to advanced industries, thereby replacing the previous source of good jobs in industries that have declined; or to support entrepreneurs who create new jobs and might even grow into large local firms; or to judiciously provide economic incentives such that their costs do not undermine the ability to maintain quality schools and infrastructure that are foundations of real economic development. Perhaps one day the field of economic development planning will have progressed to the point where it is no longer necessary to state that economic development does not automatically equal economic growth. Nor will the use of the term development need to be qualified by sustainability; instead, it will be integral to the concept. Likewise, it will not be necessary to say sustainable and equitable; instead, it will be understood that the two terms have significant areas of mutuality. But for the foreseeable future, it will be necessary to do so to counter trends in global warming and growing inequality and to push local economic development practice to create the impetus for the fourth phase—sustainable local economic development (SLED)—to more widely permeate practice.

We offer here a three-part definition of SLED that focuses on the desired end state rather than growth-defined objectives:1

Local economic development is achieved when a community’s standard of living can be preserved and increased through a process of human and physical development that is based on principles of equity and sustainability.

There are three essential elements in this definition, detailed next:

First, economic development establishes a minimum standard of living for all and increases the standard over time.

Recognition of the need for a minimum standard of living in economic development translates into not just job creation but also job creation that provides living wages (earnings for full-time work that are high enough to lift individuals and families out of poverty). A rising standard of living is associated with consumption of better goods and services and quality housing as well as increasing the number of households receiving paid health care plans, being able to save for retirement, and being able to provide vocational or collegiate education for their children.

Second, economic development reduces inequality.

While the “economic development as economic growth” approach can mean that there is more wealth and assets, it does not try to ensure that everyone benefits from the additions to the economy. Consequently, certain groups and certain places not only are left behind but also can have a harder time securing the standard of living they once knew because economic growth has driven up the costs of living for all. Thus, economic development reduces inequality between demographic groups (age, gender, race, and ethnicity) as well as spatially defined groups such as indigenous populations versus in-migrants, or old-timers versus newcomers. Likewise, it reduces inequality between different kinds of economic and political units (small towns versus large cities, inner city and suburbs, rural and urban areas).

Third, economic development promotes and encourages sustainable resource use and production.

If economic development does not incorporate sustainability goals, then its process can create inequality between the present and future generations. Economic development requires recycling the goods cast off by an increasingly affluent and consumer-oriented society as well as greater controls on growth to stem greenfield consumption and sprawl proliferation. Rising standards of living that are attained through sustainable resource use and production require different approaches to economic development (increasingly characterized as green development). They also create demand for new kinds of products, markets, jobs, firms, and industries that do not harm the environment and may even help it.

Theories of Growth and Development

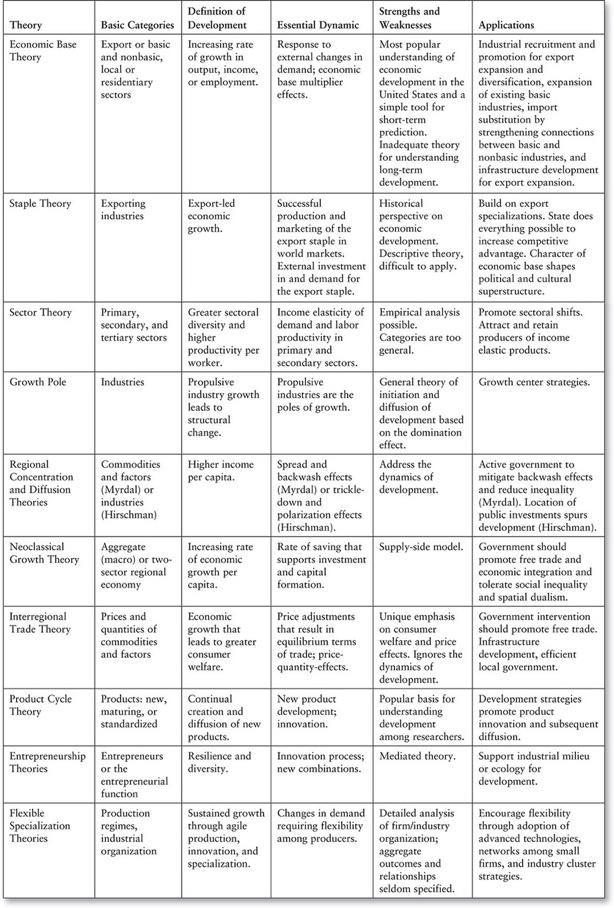

Local economic development is an evolving field and, as we contend previously, should be distinguished from economic growth. Most of the body of theory that historically has sought to explain regional or local economic development has not made this distinction. Malizia and Feser’s (1999) summary of all the significant economic development theories through the end of the past century is provided in Appendix 3.1. It describes each theory’s underlying definition of development, strengths and weaknesses, and applications.

Further, Malizia and Feser (1999) did make a distinction between whether the theories actually focus on growth or development. Unlike the previously given distinction between growth and development, which clearly has normative elements, their distinction was simply descriptive (see Malizia and Feser, 1999, Chapter 11). They categorized growth theories as those that focus on the near-term expansion of the local economy and include, among others, economic base and neoclassical economic theory. Development theories are those that focus on the long-term process of evolutionary and structural change of an economy and include, among others, staple and entrepreneurship theories. But as Malizia and Feser (1999) stated, “Theory offers the underlying principles that explain the relationships we observe and thereby motivates and informs our action” (p. 16). Thus, if we find that growing inequality and global warming are problems that require action, then our theory of economic development will identify the causes of these problems and the principles by which to address them.

In this chapter, we focus on five theoretical strands that are either influential or descriptive of local economic development.2 We discuss some developments since 2000, as well as the new directions economic development theory will need to take to explicitly incorporate sustainability.

We begin more generally, however, by describing several partial theories that point to the historical underlying rationale of local economic development. The sum of these theories may be expressed as follows:

Local and regional development = c × r, where c equals an area’s capacity (economic, social, technological, and political capacity) and r equals its resources (natural resource availability, location, labor, capital investment, entrepreneurial climate, transport, communication, industrial composition, technology, size, export market, international economic situation, and national and state government spending). A c value equaling 1 represents a neutral capacity that neither adds to nor detracts from the resources of a community. A c value greater than 1 represents a strong capacity that, when applied to (multiplied by) resources, increases them. Strong organizations that can form effective partnerships to meet the needs of the local economy can multiply resources. And a c value less than 1 represents weak community capacity (low-functioning social, political, and organizational leadership), whether due to cronyism, corruption, self-interest, disorganization, or ineptitude that, when applied to resources, decreases them and hampers development.

Resource capacities are measured in many ways, and different theories give preeminence to different resources, including raw materials, infrastructure, government spending and markets, size of markets, access to money, and access to communications.

Theories of economic development have traditionally focused mainly on the r part of the equation (resources), neglecting the c part (capacity). For example, location theories emphasize the advantages that come from being close to markets. But central cities, though close to markets, are economically lagging because they lack the social and political capacity to take advantage of their geographical advantages. Other theories focus primarily on infrastructure and the need to invest in any number of programs, such as building industrial parks, roads, airports, baseball stadiums, or telecommunications hubs. But these resources, in the absence of fully developed programs to utilize them, do not add to the community capacity: Witness the thousands of rural industrial parks that have failed to attract businesses and remain empty. Thus, any theory of local economic development must consider resources and capacity together.

More community capacity can make up for limited resources in local economic development. A community lagging in the amount and variety of resources must work harder to use the resources available most effectively. Of most obvious benefit for local economic development are natural resources, such as iron ore, coal, forests, water, and agricultural land. However, natural resources are not enough for a strong economy, and they often shape the economy in ways that rely on excessive primary processing, which historically has often been associated with unstable and low-paying jobs. Most strong economies find their advantages in features other than natural resources. Labor, capital, infrastructure, proximity to new technologies, access to trade, federal government spending, and other factors are even more advantageous inputs to economic activity, and local areas that have ample and easy access to these resources can create better economic opportunities.

However, from a development perspective, resources are often underused, and this is where local capacity comes in. The more varied types of capacity a local community has, the greater its ability to turn resources into development opportunities. For example, communities need an economic development organization (e.g., a business association, chamber of commerce, economic development corporation [EDC], or government agency for economic development) to effectively address the issues and problems of a lagging economy and enhance available resources.

Neoclassical Economic Theory

Neoclassical theory offers two major concepts for regional and local development: (1) equilibrium of economic systems and (2) mobility of capital. It asserts that all economic systems will reach a natural equilibrium if capital can flow without restriction—that is, capital will flow from high-wage/cost to low-wage/cost areas because the latter offer a higher return on investment (ROI). In local development terms, this would mean that ghettos would draw capital because prices for property and sometimes labor are lower than in the overall market. If the model worked perfectly, then all areas would gradually reach a state of equal status in the economic system. Much of this rationale has underlaid the recent wave of deregulation of banking, airlines, utilities, and similar services. In theory, all areas can compete in a deregulated market.

Neoclassical economic theorists like Nobel Prize winner Milton Friedman oppose any form of government or community regulations on the movement of firms from one area of the nation to another or even to other countries. They also oppose any restrictions on firms, such as those requiring minority or local equity participation, that could make it less advantageous for firms to locate in an area. They suggest that such regulation is doomed to fail and disrupt the normal and necessary movement of capital. Moreover, they argue that there should be no attempts to save dying or uncompetitive firms. Workers who lose their jobs should move to new employment areas as a further stimulus to development in such places.

These theories have been tested both in the United States and abroad. In developing nations, the International Monetary Fund (IMF), which oversees international emergency loans to nations, has required national governments to divest themselves of controls of assets and to reduce market and currency controls. The immediate impacts on these economies have been very severe—though in many instances, like that of Mexico, the national economy has rebounded and is now making enormous strides. Detractors of IMF policy, for example, point to the increasing gap between the rich and poor in countries with deregulated economies to suggest that the market is not evenhanded in allocating resources and that some government controls and interventions are essential to deal with inequities.

Many regional and local economic development advocates reject neoclassical theories and the policies derived from them. Blair (1995), for example, pointed out that the development promoted by such theories “should not mask the fact that there are often some groups that will benefit from growth more than others” (p. 170). Furthermore, the neoclassical framework is generally viewed as antagonistic to the interests of communities as places with a raison d’être beyond their economic utility. Finally, classical models tell us little about the real reasons why some areas are competitive while others fail.

Nevertheless, some useful concepts can be derived from the neoclassical economic theory. First, in a market society, all communities must ensure that they use their resources in a manner that attracts capital. Artificial barriers, low-functioning governmental bureaucracy, and a poor business climate are barriers to economic development. Second, communities or disadvantaged neighborhoods can and should attempt to gain the resources necessary to assist them to reach an equilibrium status with surrounding areas. This can partially be accomplished by upgrading commercial properties through local government loans and grants as well as by offering training and other programs that enhance the value of local labor. These measures can act as inducements to equalize the value of inner-city neighborhoods and other disadvantaged areas with more prosperous places.

Economic Base Theory

Economic base theory proposes that a community’s economic growth is directly related to the demand for its goods, services, and products from areas outside its local economic boundaries. The growth of industries that use local resources (including labor and materials) to produce goods and services to be exported elsewhere will generate local wealth and jobs.

The local economic development strategies that emerge from this theory emphasize the priority of aid to and recruitment of businesses that have a national or international market over aid to local service or nonexporting firms. Implementation of this model would include measures that reduce barriers to the establishment of export-based firms in an area, such as tax relief and subsidy of transport facilities and telecommunications or establishment of free trade zones.

Many of the current entrepreneurial and high-tech strategies aimed at attracting or generating new firms draw on economic base models. The rationale is that nonexporting firms or local service-providing businesses will develop automatically to supply export firms or those who work in them. Moreover, it is argued that export industries have higher job multipliers than local service firms. Thus, every job created in an export firm will generate—depending on the sector—several jobs elsewhere in the economy. There are regional economic methods that will test and measure such impacts of firms on the local economy.

It is important to understand that economic base theory is applicable in the short run only because its export sectors and economic structure—its primary focus—change over time. Staple theory is an extension of export base theory that has a long-run view. It seeks to explain a local economy’s evolution based on how its export specialization changes over time. The staple of the economy is defined as an internationally marketable commodity (such as a natural resource or agricultural product) that generates related manufacturing activity (to process the staple), which generates supplying industries and attracts outside industries seeking to take advantage of a growing market (Malizia and Feser, 1999).

A key weakness of the economic base model is that it relies on satisfying external rather than internal demands. Thus, it ignores opportunities for import substitution that can provide another means of generating jobs and income in the local economy (and stop the leakage of income outside the economy in the purchase of imports). Overzealous application of the economic base model can lead to a skewed economy almost entirely dependent upon external, global, or national market forces. This model is, however, useful in understanding how a local economy grows or declines from changes in external demand for the goods and services it sells to the outside world. It is also useful for proactive industry sector targeting aimed for achieving economic growth, development, and stability. In Chapter 6, we discuss the methodology for determining the export base of a local economy.

Product Cycle Theory

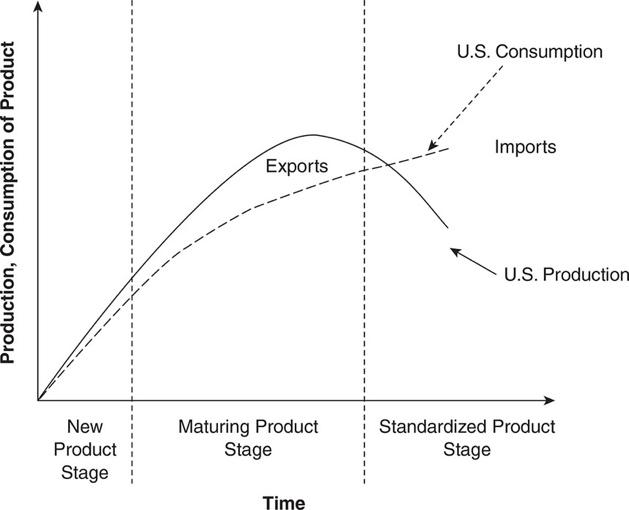

One aspect of economic base theory involves understanding industry product cycles that explain the fate of regions and localities through the innovation and diffusion process. Product cycle theory was first proposed by Raymond Vernon (1966), who showed how product development must take place in areas with greater wealth and capital to invest in the process of inventing and developing new products, supported by local markets that can pay higher prices for products that have not yet become standardized. For example, new electronic products are likely to find first markets in areas where there are affluent and educated persons, not in areas lacking the income and skills with which to purchase and use these items. Over time, the product becomes standardized, and it enters mass production and markets. Its production process becomes so routine that it no longer needs to be done by specialized labor; thus, there is a decline in the wages and skills (or good jobs) it generates. At that point, production can move to less developed economies, where firms compete not on the basis of unique products but rather on price (Figure 3.1).

Figure 3.1 The Product Cycle

Source: Adapted from Vernon (1966).

Malizia and Feser (1999) described the theory in this way:

Economic development is defined as the creation of new products and the diffusion of standardized products. Development originates in the more developed region and is exported to the less-developed region through trade and then investment. Establishing a new industry in the less-developed region creates a progressive force that can help eliminate the barriers to interregional equality. Yet product cycle theory does not predict convergence of regional incomes; the development process can be convergent or divergent. (p. 177)

The firms in a region and their prospects are both shaped by their place in the product cycle. Some industries have fast-changing product cycles in which new products are rapidly introduced, whereas other industries are relatively stable. For example, high-tech electronics industries are almost by definition rapidly changing, with diffusion of one product after another to cheap production elsewhere. Other industries are more tightly bound to their central location, and product innovation is not a factor. In investment banking, for example, each decision is so specialized that there is little potential to standardize.

Location Theories

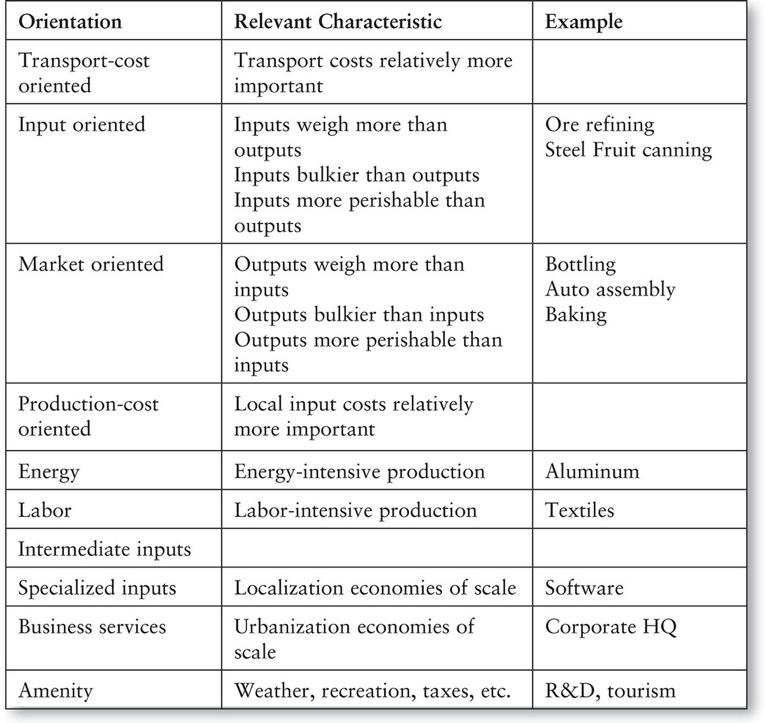

Location theories seek to explain how firms choose their locations; thus, they also provide explanations for how local economies grow (or decline). Firms maximize profits by selecting locations that minimize their costs of production and of transporting goods to market. Early location theory focused on whether the product a firm created gained or lost weight in its production process, thereby either increasing or decreasing the transport costs of the final product relative to the inputs from which it was created. To minimize transport costs, a firm with a final product that weighs less than its inputs will locate at the source of the inputs and ship the final product to market. Such firms are labeled weight losing or input oriented in standard economics, and some classic examples of products they produce are listed in Table 3.1. If the final product created by a firm weighs more than its inputs, then the firm will locate at its markets, transporting the inputs required for production. Such firms are market oriented or weight gaining.

Source: Bogart, William Thomas, The Economics of Cities and Suburbs, 1st edition, © 1998, p. 61. Reprinted by permission of Pearson Education, Inc., Upper Saddle River, NJ.

Location theory also considers other factors besides transportation costs that influence a firm’s location. With the significant advances in efficiencies in the past three decades in trucking and ocean and air cargo transport, the influence of transportation costs on firms’ location decisions has declined significantly. Today, it is more appropriate to think in terms of logistics rather than simply transportation costs. The logistics industry encompasses a range of activities for planning, storing, and controlling the flow of goods, services, and related information from point of origin to point of consumption. This includes not only transportation but also warehouse and distribution activities. Advances in information technology (IT) applications for logistics have played a key role in the development of our global production and market network.

Beyond transportation and logistics, other factors that affect the quality or suitability of a location are labor costs, the cost of energy, availability of suppliers, communications, education and training facilities, local government quality and responsiveness, and waste management. Different firms require differing mixes of these factors to be competitive. Therefore, communities generally attempt to manipulate the cost of several of these factors to become attractive to industrial firms. All of these actions are taken to enhance a location beyond its natural attributes.

In Table 3.2, we also see a reference to localization and urbanization economies of scale. These two concepts are variations of a key concept in the study of urban and regional economics—agglomeration economies—which refers to the cost savings that arise from spatial proximity. In other words, a local or regional economy generates particular production cost savings that a firm would not realize if it were located in an undeveloped area. Localization economies of scale mean that firms benefit from locating near other firms because they may use the same type of labor or inputs, or there is better access to information about competitors, suppliers, new technologies, and so on. Urbanization economies of scale mean that the larger the local economy (i.e., the bigger the city), the greater the production cost savings and other benefits to the firm. These can derive from access to larger markets, to more specialized services (e.g., industrial designers, advertisers, venture capitalists), or to the transfer of knowledge and technologies between one industry sector and another in the larger economy.

The location of firms in overall economic space has long been of interest to economic developers (Malizia and Feser, 1999). Some of the early theorists who dealt with the issue of location during the 1950s include François Perroux (1983), who described “growth poles”; Gunnar Myrdal (1957), who produced a theory of cumulative causation; and Friedmann and Weaver (1979), who offered a core–periphery model.

Perroux’s (1983) growth pole theory hypothesized that growth is stimulated by cutting-edge industries, firms, or other actors who are dominant in their field. Perroux wanted to refute the claim of classical theorists that growth would flow to less costly areas. In fact, the opposite often occurs with “propulsive industries” that have an edge in technology, wealth, and political influence. Perroux argued that these growth poles were linked to other growth poles but not necessarily to the periphery area of the central growth node. This helps explain why not every community in Silicon Valley, like Oakland or East Palo Alto, benefits from rapid economic growth in a nearby fast-growing area.

Myrdal’s (1957) theory of cumulative causation sought to explain why some areas are increasingly advantaged while others are disproportionately disadvantaged. Market forces, by their nature, pull capital, skill, and expertise to certain areas. These areas accumulate a large-scale competitive advantage over the rest of the system. Casual observation of the decay of urban neighborhoods demonstrates the basic concept of cumulative causation: The interplay of market forces increases rather than decreases the inequality between areas so that a divergence in regional income is a predictable result. Myrdal (1957) gave the following example of cumulative causation:

Suppose accidental change occurs in a community, and it is not immediately canceled out in a stream of events; for example a factory employing a large part of the population burns down …and cannot be rebuilt economically, at least not at that locality. The immediate effect is that the firm owning it goes out of business and its workers become unemployed. This will decrease income and demand. In its turn, the decreased demand will lower incomes and cause unemployment in all sorts of other businesses in the community which sold to or served the firm and its employees…. If there are no exogenous changes, the community will be less tempting for outside businesses and workers who had contemplated moving in. As the process gathers momentum, businesses established in the community and workers living there will increasingly find reasons for moving out in order to seek better markets somewhere else. This will again decrease income and demand. (p. 23)

Advanced technology and telecommunications have altered the significance of specific locations for the production and distribution of goods that early location theory sought to explain. Communities of significantly smaller sizes can compete with large cities for certain firms and industries because IT and reduction in transport costs have reduced the significance of distance in location decisions. Less tangible variables, such as the quality of community life, cultural and natural amenities, and reasonable cost of living, can now assume greater weight in the firm’s location decision based on the preferences of the owners or the workers required by the firm. Rather than local economic developers being limited by the natural attributes or original features of a location for encouraging firm location, they now have the opportunity to improve the factors in location decisions that have surpassed the importance of minimizing transportation costs or physical proximity to markets for many firms.

Central Place Theory

Central place theory is a variant of location theory that is most applicable to retail activity. According to this theory, each urban center is supported by a series of smaller places that provide resources (industries and raw materials) to the central place, which is more specialized and productive. These smaller places are in turn surrounded by even smaller places that supply and are markets for the larger places. The urban center contains specialized retail stores that serve the entire region; professional specialists such as corporate lawyers, investment bankers, and heart surgeons; and headquarters for corporations as well as nonprofit organizations. When inhabitants of a very small place need a specialized product or service, they must go to the central place, though they can find many less specialized products and services in their own community. For example, residents of a small place do not need to go to the central city for groceries or car repair, though they must leave home to hear a performance by a world-class symphony orchestra.

Regional development models for rural areas have relied heavily on central place theory to guide resource allocations on the assumption that the development of a central place will improve the economic well-being of the entire region. The application of central place theory can be observed in rural service bureaucracies like the Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA), the Rural Electrification Administration (REA), and the U.S. Economic Development Administration (EDA). Each of these organizations attempted to develop a regional economic plan with one or two communities either designated or emerging as regional nodes for development.

However, as Bradshaw and Blakely (1979) observed three decades ago, rural communities in advanced industrial society are increasingly able to take advantage of specialization that once was limited to urban areas. While lacking some of the advantages that are available in urban settings, such as proximity to other specialists, rural communities are competing for advanced manufacturing, professional services, sophisticated communications, and other types of businesses because people value the rural environment and are willing to use electronic linkages to minimize the disadvantages of being located in a small place. The Internet and the megamall have greatly altered the commercial relations of central and peripheral places. Today, several billion dollars a year are spent by consumers in Internet transactions with both existing retailers and new e-tailers.

Central place theory has relevant applications for both urban and rural local economic development. It is necessary, for example, to differentiate the functions of various neighborhood areas so that they can remain viable centers. Some areas will become regional core cities serving an entire region; others will be smaller villages or towns that serve only the local resident community. Local economic development specialists can assist communities or neighborhoods to develop their functional role in the regional economic place hierarchy and electronic hierarchy.

At the same time, central place theory is unable to explain why, within major market areas, individual neighborhoods can be seriously lacking in retail services. This is particularly the case in low-income and minority neighborhoods and has been the focus of economic development attention since the late 1990s, leading to the development of the “new markets” strategy discussed next.

Translating Theory Into Practice

Economic development theory has influenced practice, as the following sections demonstrate.

Attraction Models

Models of community attraction are based on location theory and employed widely by communities seeking economic development. Communities across the globe have initiated policies and programs to make their area more attractive to investors, firms, new migrants, entrepreneurs, and others and thereby to gain a competitive advantage over other areas with similar resource endowments.

The basic assumption of attraction models is that a community can alter its market position with industrialists by offering incentives and subsidies. This assumes that new activity will generate taxes and increased economic wealth to replace the initial public and private subsidies. A more cynical view, supported by considerable evidence, is that the cost of such efforts is, in fact, paid by the workers and taxpayers of the community while the benefits go largely to landowners and firms (Bluestone, Harrison, and Baker, 1981). Consequently, inequality can increase.

A new approach in attraction is the change in emphasis from attracting factories to attracting entrepreneurial populations—particularly certain socioeconomic groups—to a community or area. New middle-class young retirees to an area bring both buying power and the capability to attract employers. In addition, recent migrants are more likely to start new firms. As a result, many communities have reassessed their firm attraction efforts and reoriented them toward “people” attraction. This approach has been particularly effective in rural areas where the quality-of-life factor can attract new populations—leading to increased economic growth as a response to both internal demand and new export enterprises created by the new migrants. Furthermore, it has been suggested that some localities can offer special “knowledge networks” to act as incubators for high-tech firms or inventors. These areas are increasingly described as “innovation districts.”

In attraction models, communities are products. As such, they must be “packaged” and appropriately displayed. The objective evidence of this packaging can be observed in magazine and newspaper advertisements extolling the virtues of certain places over other communities. Anecdotal evidence suggests that community promotion works and that failure to use it may be a political liability. No city or neighborhood should hide its virtues “under a bushel basket.” Some form of marketing is necessary, though the means and the rationale are as important as the desired result in undertaking this mode of development planning, since the ends have not always justified the means in the past. Communities have also learned from the past, and a growing number are adding restrictions or conditions to the public incentives they offer to attract firms. These are intended to recoup the public investment made if the firm does not stay in the community long enough to generate taxes and wages that meet or exceed the investment. The conditions imposed can also specify that the jobs created by the firm go to local residents and pay living wages.

New Markets Model

According to the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD), in the year 2000, America’s inner-city neighborhoods possessed an unrealized potential purchasing power of $331 million, or nearly one third of the retail capacity of the nation’s urban cities. Rural areas containing new migrants also have large unrealized market potential—for example, the counties that make up the Kentucky highlands in Appalachia are estimated to have more than $1.3 billion in retail purchasing power (Cuomo, 1999). The reason these communities are underserved relates to misperceptions and poor information regarding these markets. Retailers have either left these communities or resisted serving them because of the belief that incomes were too low and crime too high to make such markets valuable. But as the national economy has prospered, crime in these communities has fallen to levels that have not been observed for more than three decades. Further, while inner-city household incomes may be lower than those of the suburbs, the greater population density creates higher foot traffic and strong buying power. Moreover, employment participation in both the inner city and rural areas has increased. Finally, the Internet has equalized opportunities for many rural areas to draw service jobs.

According to Michael Porter (1995), inner-city areas have features that place them in the forefront of the New Economy. Not only do they have proximity to a large downtown area with concentrated activity, making them prime markets for retailing, but also, more importantly, they have proximity to crucial competitive clusters:

The most exciting prospects for the future of inner city economic development lie in capitalizing on nearby regional clusters: those include close-to-a-region collections of related companies that are competitive nationally and even globally. For example, Boston’s inner city is next door to world class financial services and health care clusters. South Central Los Angeles is close to an enormous entertainment cluster and a large logistical-service wholesaling complex. (p. 60)

In the new markets model, ghettos and declining rural areas are economic opportunity zones that are not being utilized appropriately. Economic development of these areas, according to James Carr (1999, p. 20), requires the following:

Understanding the value of community assets

Creating or matching financing tools to these assets

Designing value-recapture mechanisms to recycle the new wealth generated by these assets back into the communities from which they originated so that these resources can stimulate more economic activity in the community, from new businesses and housing to social and community services

Determining ways in which the wealth generated can be shared by a wide range of community members

Developing methods to evaluate the long-term benefits of these investments

Although these concepts increase the opportunity for new investment and reinvestment in inner-city and low-income areas, they also require some form of subsidy to get started. New forms of economic finance, such as community development financial institutions (CDFIs), have been created to enhance both equity and debt finance targeted to low-income areas. The creation of these new financing vehicles, combined with a new infusion of capital from the federal treasury in the form of $26 billion in loan guarantees, acts as a stimulus for larger firms to take the risk of investing in low-income areas. But an even greater stimulus for brand-name firms like Gap and Starbucks to invest in the inner city is the need to find new consumers via brick-and-mortar retailing. Furthermore, the influx of immigrants to formerly low-income, predominantly Black neighborhoods has altered the market opportunities for retailers in these communities. The new markets model is the creative realization of old market economics in a new economy.

Theories, Models, and Fads in Local Economic Development Planning

In this chapter, we have highlighted five significant theories that have been employed to explain local economic development outcomes and to shape planning for economic development (albeit where development is equated with growth). Economic development is not an academic discipline per se but rather a field or subfield in which scholars specialize from a number of disciplines, including business, city and regional planning, demography, education, economics, geography, political science, public policy, regional science, and sociology. Theories of economic development, consequently, can be influenced by any of these disciplines. We noted at the beginning of this chapter that local economic development is an evolving field. Further, as we will discuss in Chapter 4, those working in the field come from a wide variety and range of levels of academic and professional experiences.

Overall, economic development professionals are action oriented. Indeed, their jobs often depend on producing results. They are drawn to new ideas and theories to help them do so for their localities. While their motivations are laudable, past experience has shown that they sometimes latch on to unproven ideas and theories to which the always-limited resources of time, personnel, and dollars are committed. A particularly notable example occurred during the 1980s, when David L. Birch (1979) put forward the theory that small business is the true engine of the economy and job creation as well as the true source of innovation. This was based on findings from his analysis of Dun & Bradstreet data that 80% of the jobs created between 1969 and 1976 were produced by businesses with fewer than 100 workers and nearly two thirds by firms with fewer than 20. However, his methodology was subsequently faulted (White and Osterman, 1991), and it was ultimately concluded that “the largest business organizations continue to account for the great majority of jobs, to pay the highest wages and benefits, and to dominate the coordination of production among networks of firms, the control of finance, and the adoption and implementation of new technology” (Harrison, 1994). By this time, however, localities throughout the country were already on the “small business bandwagon,” using their resources to create new centers and programs to foster small business. Encouraging small business development is not a bad economic development idea, but it was also not the panacea for economic development problems brought on by restructuring and employment shedding of the U.S. manufacturing industry during the 1980s and beyond. Economic development professionals needed to maintain focus and assistance to manufacturing plants and other large firms that formed the economic base of their communities.

We introduced two recent and very popular theories in Chapter 1 that are currently garnering a lot of economic development attention: Kim and Mauborgne’s (2004) “blue ocean” theory and Richard Florida’s (2002) concept of the creative class. Blue ocean is focused on firms that create new markets, which in turn will bring substantial economic development to localities in which they are located. In contrast, the creative class theory focuses on people as drivers of economic development. Each concept has garnered substantial attention and generated private- and public-sector initiatives for economic development. But each is receiving substantial criticism for claims of originality, the analysis used to prove its theses, and the validity of its theories.

On the creative class, Jamie Peck (2005) observed the following:

[The thesis] that urban fortunes increasingly turn on the capacity to attract, retain and even pamper a mobile and finicky class of “creatives,” whose aggregate efforts have become the primary drivers of economic development—has proved to be a hugely seductive one for civic leaders around the world, competition amongst whom has subsequently worked to inflate Florida’s speaking fees well into the five-figure range. From Singapore to London, Dublin to Auckland, Memphis to Amsterdam; indeed, all the way to Providence, RI, and Green Bay, WI, cities have paid handsomely to hear about the new credo of creativity, to learn how to attract and nurture creative workers, and to evaluate the latest “hipsterization strategies” of established creative capitals like Austin, TX or wannabes like Tampa Bay, FL: “civic leaders are seizing on the argument that they need to compete not with the plain old tax breaks and redevelopment schemes, but on the playing fields of what Florida calls ‘the three Ts [of] Technology, Talent, and Tolerance’” (Shea, 2004: D1). According to this increasingly pervasive urban-development script, the dawn of a “new kind of capitalism based on human creativity” calls for funky forms of supply-side intervention, since cities now find themselves in a high-stakes “war for talent,” one that can only be won by developing the kind of “people climates” valued by creatives—urban environments that are open, diverse, dynamic and cool (Florida, 2003c: 27). Hailed in many quarters as a cool-cities guru, assailed in others as a new-economy huckster, Florida has made real waves in the brackish backwaters of urban economic development policy. (p. 740)

Returning to our distinction between growth and development, the creative class thesis has been criticized for prescribing strategies that do not address issues of inequality, gentrification, and the working poor and for focusing on a narrow concept of diversity as an enabler of economic development (e.g., gays only). Thus, even if its premise about what causes economic growth is correct (and at least one author—Malanga [2004]—has published data that claims the so-called creative class cities have underperformed compared to the traditional corporate and working-class cities), a wholesale adoption of creative class development strategies could exacerbate the enduring economic development problems of inequality and improving the standard of living for the poor. As was the case with the small business development fad, economic developers need to critically assess the creative class thesis before devoting substantial community resources to its pursuit.

The Continued Evolution of Economic Development Theory Into Local Practice

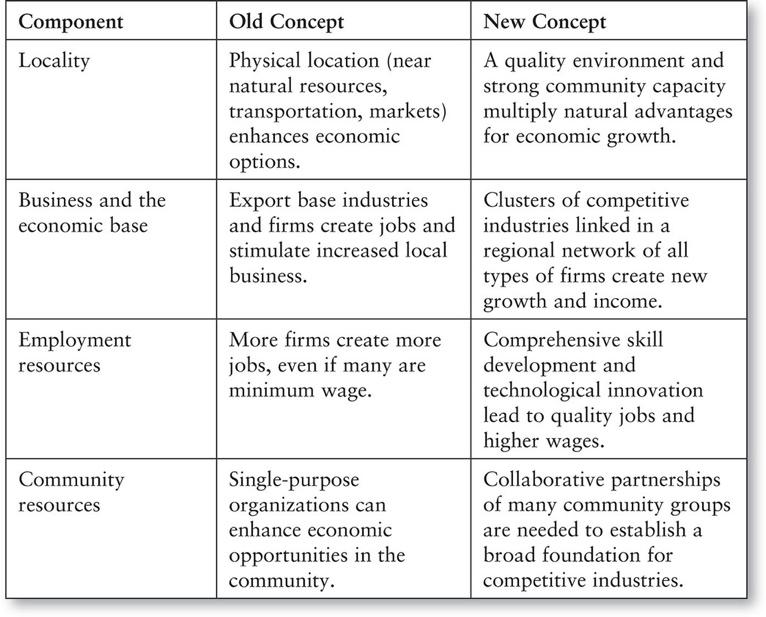

Existing development theories must evolve in order to reflect changing economic structures and maintain relevance for local economic development activities. In Table 3.2, we have reformulated the concepts emphasized by various theories—locality, business and the economic base, employment resources, and community resources—to create a new foundation for local economic development.

Locality

Technology has shattered the traditional view of physical location as the major determinant of development. Firms—even large-scale manufacturing operations—are not as tied to a specific location as they used to be, especially as they reduce dependence on natural resources and substitute the more mobile resource of knowledge as their critical input. Firms increasingly have the ability to be footloose. And even those firms that choose to stay put have the ability to outsource increasingly advanced tasks due to the globalized information and production network. What is known is that firms consistently value a place in which physical and social or organizational factors cooperate to make a quality environment in which to live and do business. Thus, the traditional view that the availability of transportation and market systems determines a community’s economic viability is outmoded.

The new location logic is most clearly seen in the changing opportunities for rural economic development. Whereas rural communities previously spent most of their energy attempting to acquire roads, industrial parks, and related infrastructure to promote manufacturing development, they now find this strategy less productive. Fewer footloose firms are finding remote rural areas attractive at any cost, regardless of services, especially when they can relocate to Mexico, Asia, or many other places across the globe that provide cheap labor to produce goods that can be inexpensively shipped to markets due to logistics advances. Instead, growth in rural areas seems to follow from a pristine natural environment for recreation and ambiance and a quality social infrastructure, including civic organizations, cultural opportunities, and business networks. Thus, some rural areas are growing even without such large-scale investment in infrastructure. It does not seem to matter whether a rural community is a designated population growth center or a target area for increased industrial development or resource exploitation. A rural area’s economic opportunities are determined by the quality of the available human resource base and preservation, rather than exploitation, of its natural resources.

Location, by itself, is no longer a “pull” factor. But the new local economic development model suggests that there are locational development-inducing factors. These factors apply more to the quality of the local physical and social environment than to larger-scale geographic considerations. Moreover, the development of a community’s recreational, housing, and social institutions can determine economic viability. When a community concentrates on building a social and institutional network, it creates an inviting environment for a firm to develop or locate there. If the structure is organized properly, economic activity will ensue—it will not have to be pursued.

Business and the Economic Base

The economic base model relies heavily on a sectoral approach to economic development. The approach concentrates on transactions within the economic system rather than the failures and inadequacies of the system in which the transactions are taking place. This approach is based on the notion that the local economy must maximize its internal institutional linkages in the public and private sectors.

Local economic development theory builds on the premise that the institutional base must form a major component of both finding the problems in the local economy and altering institutional arrangements. Building new institutional relationships is the new substance of economic development. Communities can take control of their destiny when and if they assemble the resources and information necessary to build their own future. This is not a closed political process but an open one that places local citizens in a position to plan and manage their own economic destiny.

In the New Economy, business remains important to the economic development agenda, but the focus has shifted from individual firms to networks of firms or clusters of interdependent firms in industries in which human, natural, and technological linkage advantages are present. Rather than providing special incentives to individual firms, economic development involves brokering among firms to explore how they can benefit from each other. It also involves shifting business practices to those that are environmentally benign and helping firms create new sustainable products and processes that may well use as their inputs the wastes of other firms.

Employment Resources

Boosting local employment has been the major and sometimes the sole rationale for communities to engage in active development efforts. In the neoclassical model, lower wage rates and cheaper costs are sufficient to create employment. This model thus suggests that areas benefit from having low-cost labor, which often is linked to low taxes and limited education and training opportunities. Firms are recruited on the basis of how many jobs they can provide, regardless of the skill level or wages paid. Too often, firms enter areas seeking low wages and generate many minimum-wage jobs that leave residents of the local community in poverty. This does not raise the community’s standard of living, reduce its level of inequality, or provide a foundation for sustained development.

Firms in our advanced economy need highly skilled labor and are willing to pay for it. Highly competitive firms recognize that the firm and the community must continuously invest in assuring a highly skilled workforce. The myriad job training and job development schemes in this country are testimony to the importance of transforming the existing labor force into a more productive resource for existing and new employers.

The quality of an area’s human resource base is a major inducement to all industries. If the local human resource base is substantial, either new firms will be created by it regardless of location or existing firms will migrate there. Therefore, communities must not only build jobs to fit the existing populace but also build institutions that expand the capability of this population. Rural communities and inner-city neighborhoods seldom have higher education or research institutions that serve them. Indeed, rural communities and urban neighborhoods seldom consider the need for such resources beyond the teaching function or community problem-solving requirement.

Local economic development, however—both now and in the near future—will be dependent on the ability of communities to use the resources of higher education and research-related institutions. Rather than attracting a new factory that may initially employ thousands, a community may be better served by attracting and retaining a few small, related research labs in leading-edge technologies that could eventually create jobs and stability for the total region.

The goal of local economic development is to enhance the value of people and places. Thus, the community builds economic opportunities to “fit” the human resources and utilize or maximize the existing natural and institutional resource base. In essence, the emphasis shifts from the demand (firm) side of the equation to the supply side of labor and natural resources.

Community Resources

In the classical model, the economy is developed by a business-oriented organization that can advocate for the interests of the firms in the region. In the New Economy, the community has many organizations representing diverse interests, and only through a collaboration among the organizations is economic development possible. For example, government, business organizations (such as chambers of commerce), workforce development organizations, and community-based organizations must work in partnership to ensure that the necessary preconditions for economic development are present. The entity responsible for delivering economic development is no longer one organization but a virtual organization made up of all the organizations that can contribute to the success of a particular economic development project and then, when that project is completed, disband, to be replaced by a different network of organizations that are appropriate for the next project.

Conclusion

The conceptual and theoretical framework for economic development shown in Table 3.2 defines the changing context for economic development in our advanced economy. It suggests that local economic development is not as “spatially free” as the market and that old efforts focused on single-minded expansion of firms and jobs will not generate local well-being in the economy. In the changing economy, specific locations must be tied to specific people. In local economic development, we are concerned with both people and place. Therefore, local economic development is a process that emphasizes the full use of existing human and natural resources to preserve and increase a community’s standard of living that is based on principles of equity and sustainability.

Old theories are not necessarily incompatible with the definition of economic development we put forth in this chapter. But this definition does ask for a careful consideration of the impacts of uncritical application of strategies based on these theories. In an increasingly technological age, the old emphasis on employment generation actually has increasing merit. But it must be qualified to focus on good jobs and to prepare workers and their communities for more dynamic labor markets and ongoing skill development to be relevant in these labor markets.

Thus, economic development theory must evolve to meet the challenge of explaining how communities create strong foundations for sustainable economic development that counters trends in global warming and growing inequality as well as preserves natural resources while raising standards of living. In turn, the public and private sectors must work together to identify and support sustainable economic development strategies. Government is responsible for reducing economic and social disparities while protecting natural resources. It uses its power and resources to foster a strong business sector that increases rather than diminishes SLED. Among other things, this requires reshaping existing strategies such as new markets as well as removing barriers in existing regulations and programs.

Source: From Malizia and Feser, Understanding Local Economic Development, 1999. Copyright © 1999, Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey, Center for Urban Policy Research. Reprinted with permission of the publisher.

Notes

1. This version of the definition of SLED was published originally in Fitzgerald and Leigh (2002). It is a refinement of a definition that Leigh originally developed in 1985.

2. The serious student of local economic development planning is encouraged to read Malizia and Feser’s (1999) comprehensive discussion of economic development theories.

References and Suggested Readings

Alonso, William. 1972. “Location Theory.” In Regional Analysis, edited by L. Needham. Harmondsworth, UK: Penguin.

Birch, David L. 1979. The Job Generation Process. Cambridge: MIT Program on Neighborhood and Regional Change.

Blair, John P. 1995. Local Economic Development: Analysis and Practice. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Blakely, Edward J. 2001. “Competitive Advantage for the 21st Century: Can a Place-Based Approach to Economic Development Survive in a Cyberspace Age?” Journal of the American Planning Association 67 (2): 133–140.

Bluestone, Barry, Bennett Harrison, and Baker Lawrence. 1981. Corporate Flight: The Causes and Consequences of Economic Dislocation. Washington, DC: Progressive Alliance Books.

Bogart, William Thomas. 1998. The Economics of Cities and Suburbs (1st ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Education.

Bradshaw, Ted K., and Blakely Edward J. 1979. Rural Communities in Advanced Industrial Society. New York: Praeger.

Carr, James. 1999. “Community, Capital, and Markets: A New Paradigm for Community Reinvestment.” NeighborWorks (Summer): 20–23.

Corporation for Enterprise Development. 1982. Investing in Poor Communities. Washington, DC: Author.

Cuomo, Andrew. 1999. New Markets: The Untapped Retail Buying Power in America’s Inner Cities. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office.

Czamanski, Stanislaw. 1972. Regional Science Techniques in Practice. Lexington, MA: D. C. Heath.

Daniels, Belden, and Chris Tilly. 1985. “Community Economic Development: Seven Guiding Principles.” Resources 3 (11): n.p.

Eisinger, Peter K. 1988. The Rise of the Entrepreneurial State: State and Local Economic Development Policies in the United States. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press.

Fitzgerald, Joan, and Leigh Nancey Green. 2002. Economic Revitalization: Cases and Strategies for City and Suburb. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Florida, Richard. 2002. The Rise of the Creative Class: And How It’s Transforming Work, Leisure, Community, and Everyday Life. New York: Basic Books.

Friedmann, John, and Clyde Weaver. 1979. Territory and Function: The Evolution of Regional Planning. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Giloth, Robert, and Robert Meier. 1989. “Spatial Change and Social Justice: Alternative Economic Development in Chicago.” In Restructuring and Political Response, edited by Robert Beauregard. Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

Goldstein, William A. 1979. Planning for Community Economic Development: Some Structural Considerations. Paper prepared for the Planning Theory and Practice conference, Cornell University, Ithaca, NY.

Hackett, Steven C. 2006. Environmental and Natural Resources Economics: Theory, Policy, and the Sustainable Society (3rd ed.). New York: M. E. Sharpe.

Hanson, Niles M. 1970. “How Regional Policy Can Benefit From Economic Theory.” Growth and Change (January): n.p.

Harrison, Bennett. 1994. “The Myth of Small Firms as Predominant Job Generators.” Economic Development Quarterly 8 (1): 13–18.

Hirschman, Albert O. 1958. The Strategy of Economic Development. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Hoover, Edgar M. 1971. An Introduction to Regional Economics. New York: Knopf.

Isard, Walter, and Stanislaw Czamanski. 1981. “Techniques for Estimating Local and Regional Multiplier Effects of Change in the Level of Government Programs.” In Regional Economics, edited by G. J. Butler and P. D. Mandeville. Brisbane: University of Queensland Press.

Kim, Chan, and Renee Mauborgne. 2004. “Blue Ocean Strategy.” Harvard Business Review 82 (10): 79–88.

Leigh-Preston, Nancey. 1985. Industrial Transformation, Economic Development, and Regional Planning. Chicago: Council of Planning Librarians Bibliography.

Malanga, Steven. 2004. The Curse of the Creative Class. City Journal (Winter). Accessed September 15, 2008. http://www.city-journal.org/hteml/14_1_the_curse_.html.

Malizia, Emil, and John Feser. 1999. Understanding Local Economic Development. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University, Center for Urban Planning Research.

Myrdal, Gunnar. 1957. Economic Theory and Underdeveloped Regions. London: Duckworth.

Peck, Jamie. 2005. “Struggling With the Creative Class.” International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 29 (4): 740–770.

Perroux, François. 1983. A New Concept of Development. Paris: UNESCO/Universite du Paris IX.

Porter, Michael. 1995. “The Competitive Advantage of the Inner City.” Harvard Business Review (May–June): 55–71.

Richardson, Harry W. 1971. Urban Economics. Harmondsworth, UK: Penguin.

Richardson, Harry W. 1973. Regional Growth Theory. New York: John Wiley.

Robinson, Carla Jean. 1989. “Municipal Approaches to Economic Development.” Journal of the American Planning Association 55 (3): 283–295.

Rubin, Herbert. 2000. Renewing Hope Within Neighborhoods of Despair. Albany: State University of New York Press.

Shragge, Eric. 1997. Community Economic Development. Buffalo, NY: Black Rose.

Vernon, Raymond. 1966. “International Investment and International Trade in the Product Cycle.” The Quarterly Journal of Economics 80 (2): 190–207.

White, Sammis B., and Osterman Jeffery D. 1991. “Is Employment Growth Really Coming From Small Establishments?” Economic Development Quarterly 5 (3): 241–257.

Williams, S. 1986. Local Employment Generation: The Need for Innovation, Information and Suitable Technology. Paris: Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development.

Wolman, Harold, and Gerry Stoker. 1992. “Understanding Local Economic Development in a Comparative Context.” Economic Development Quarterly 6 (4): 415.