for AAA paper only homework

Chapter 5

Macro-foundations of Strategic Advantage: Industry Analysis

| Why console gaming is dying? Since 2010, console-based video games industry has slumped. The waning consumer interest has hurt the big three consoles: Microsoft's Xbox 360, Sony's PlayStation 3 and Nintendo's Wii. The console game industry has kept alive because of a select few big game franchises like “Call of Duty” and “Madden”. However, the industry’s future is uncertain. In the past, each next generation of consoles was a step above, and thrived on differentiation. Nintendo NES was a step above Atari and imprecise joysticks. Genesis offered a huge leap in affordable home graphics. PlayStation immersed players into 3-D worlds. Xbox overcame polygons in favor of rounded looks. Current generation of consoles has largely offered better-looking versions of games consumers have already played. Next-generation is no longer “next”. Even wii, after five years of phenomenal growth, is slumping. Console industry has introduced an ever larger number of games, but fewer have gone into new creative territories and are must-have. In the recent years, gaming consoles have transformed into entertainment hubs for consumers to stream movies or web-based videos from Amazon and Netflix. 40% of all game console activity is non-game. Game consoles account for half of all Netflix users. The shift in the use of game consoles for movies has hurt the console game industry. Over the past 30 years, the business model of the console makers such as Sony and Microsoft was to spend billions in R&D and marketing costs on a new console system on a five year lifecycle, to sell them at loss for the first few years, and to make up the cost from incomes from proprietary and third-party software business - a slew of lucrative $50-$60 games. Now, the console makers are unable to recover their costs, and are incurring losses. Console makers have tried to reinvigorate interest in living-room and dedicated handheld gaming. Their mainstream consoles are quite old – in 2012, Xbox 360 was 7 years old, and the Wii and the PlaysStation 3 were both 6 years old. New motion-controlled gaming systems like Microsoft’s Kinect and Sony’s Move let players control in-game avatars by moving their arms and legs. They have helped sustain consumer interest, but not helped turnaround the console maker fortunes as anticipated. Experts wonder if a new hardware cycle is really a solution. Some suggest console makers should act more like nontraditional platforms. In 2013, a new entrant launched a console Ouya with free-to-play games and a $99 launch price, and a focus on TV gaming. Some console game developers are using the “free to play” business model to give away their games for free, and then charge players later $5 to $10 for various status upgrades or gameplay perks. This threat of cut-price rivalry is forcing lot of other console gamers to offer deals, as the customers make fewer full-price game purchases than before. In the interim, firms in social and mobile sectors have introduced novel gameplay with cheap, 99 cents, bite-size games such as “Angry Birds” and “Plants vs. Zombies” for iphones and ipads. This has exploded social and mobile based gaming, as well as the overall demand for gaming as a whole group of new players have started playing games. This new group is attracted to games for the social aspect, and is not interested in game consoles. To tap the new trends, $5-$20 on sale games have been introduced for PCs as well, breathing new life into PC gaming. Customers, the console owners, have increasingly taken to playing games on multiple platforms. They are looking for a wider spread of experiences, such as the quick, bite sized gaming sessions in-between breaks or errands. It is faster to tap an icon on the smartphone, than to go to the living room, wait for the console to power on, load the game from the main menu, and wait for it to boot. The big console makers have strived to capture a share of the social gaming pie, by retreading their older console games as cut-down smaller versions for the web, such as at XBLA (Xbox Live Arcade) and PSN (PlayStation Network). However, consumers have dismissed these as a sign of creative stagnation of the console makers in game design. Critics contend that console games need to deliver more meaningful experiences. Ubisoft's Hutchinson observes, “"We need to offer more experiences that are understandable to people's real lives, either in terms of mechanics or narrative, and attract people who don't read fantasy novels or watch the SyFy channel. Our mechanics are often not the barrier, but our content sometimes is." As the overall game industry continues to grow in size, the survival of traditional console makers will depend on how they adapt to evolving business models and changing consumer tastes. Adapted from Snow (2012) |

As illustrated by the case of the video-gaming console industry, changes initiated by other participants in the industry have a significant impact on the strategic advantage of the firms. In this chapter we discuss two major approaches for the analysis of industry linkages:

Structural approach. This approach emphasizes how firms identify and defend spaces over which they have control on.

Process approach. This approach emphasizes the possibilities of cooperative as well as competitive relationships, and of national and global-level networks and support systems.

Structural Approach - Porter’s Five Forces Framework

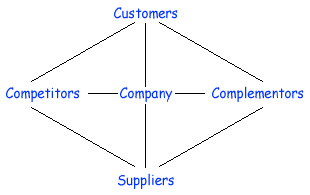

Porter’s Five Forces framework helps to analyze the structural attractiveness of an industry, in order to assess the profit potential of the firms within a value system. For instance, the profit potential of mobile network operators is influenced by their position relative to the content and service providers (“the suppliers”), and to the mobile users (“the buyers”). Presence of substitutes such as the desktops, laptops, tablets, and landlines, is also an influencing factor. Possibility of new rival entry for taking away a share of the market also influences the profit potential. Finally, one must consider the intensity of rivalry among different mobile network operators, such as whether the different rivals focus on very different target markets or strive to make inroads on one another’s target market at all costs. Exhibits 5.1 portrays these five forces in the framework – bargaining power of suppliers, bargaining power of buyers, potential threat from substitute providers, potential threat of entry from new firms, and intensity of rivalry among firms in the industry.

Exhibit 5.1: Porter’s Five Forces model

The Five Forces framework pinpoints structural factors that hinder the profit potential for any intermediate stage in the value system. It posits that the firms need to restructure or reconfigure the processes in the value system, so that they are able to move into a structurally more attractive position. For instance,

They may need to cultivate new suppliers, strengthen the commitment of current suppliers, or find ways to reduce their dependency on major suppliers.

They may also need to cultivate new buyers, strengthen the loyalty of current buyers, or find ways to reduce their dependency on major buyers.

They may further need product or service innovations, or develop complements, to offer the benefits more attractive than those offered by the substitutes, and at more competitive costs.

They may additionally need to make sure that the new entrants are playing fairly, such as not illegally imitating their knowledge, not using deceptive tactics, and not using unfair subsidies from their governments to undercut.

To preempt new entrants, they also need to continue investing in their dynamic capabilities, to remain sufficiently differentiated and cost-effective in their offerings to the customers.

The thrust of the Five Forces framework is on the industry level analysis, and interventions that enable a firm to restructure its position within an existing industry structure, or by favorably changing this industry structure. It is based on an assumption that the overall profit potential of any industry is constant, as determined by the cost structure across the value system and the final value accrued by the customers. The firms participating in the value system leading up to the final demand must find ways to capture a larger share of this industry’s profit pie. In other words, the objective of the Five Forces analysis is to improve value capture, as opposed to improving value creation.

The five forces analysis assumes that the structure of the industry influences the conduct or behavior of the participants. To improve their performance, firms must create or discover new positions where the behavior of the participants in their value system is more favorable. In other words, the analysis assumes that it is not possible to change participant behavior directly; the firms must strive to reposition themselves or change the industry structure in order to bring about a change in participant behavior. This assumption is core to the industrial organizational (I/O) theory, according to which market structure shapes participant conduct, which in turn shapes participant performance. This is referred to as the Structure-Conduct-Performance paradigm.

The Five forces framework has the following three major limitations:

Five forces analysis does not consider the independent effects of macro factors such as politics and new technologies, that may enable a firm to drive a fundamental restructuring of the entire value system and of its industry structure

Five forces analysis does not consider the independent effects of micro behavioral factors such as cognitions, emotions, and social relations, on the profit potential of an industry, irrespective of its structure. Thus, the role of knowledge (a cognitive factor) in the profit potential of an industry is overlooked. Similarly, the framework fails to consider the interactive effects of high trust, collaborative, and relationship-based culture. Information and communication technologies in the new economy require considerable cooperation among participants; a focus exclusively on a firm’s own positions may hurt its ability to participate in network exchanges and to be a resourceful solutions shop.

Five forces analysis does not consider the interactive effects of macro and micro factors, such as how participant knowledge (cognitions) may improve through interactions with new technologies, thereby allowing a firm to accrue more value.

The Five forces framework does allow firms to also evaluate how macro shifts have or might generate shifts in industry structure, and in the positions of various participants. It is also possible to evaluate the effects of changes in the participant knowledge, capabilities, and core competencies on their respective positions, and on the overall structure of the industry.

Structural Analysis using Five forces framework

Threat of Entry of New Firms. Any industry that is perceived as being highly profitable tends to attract new firms. These new firms desire to capture a share of the industry profits potential and grow by investing in production capacity and gaining market share. If the prospects for their success are good, then the existing firms will face an erosion of their own revenues, market share, and profitability. The prospects for the success of new firms depend on two factors: the entry barriers to an industry and the expected retaliation from existing firms. The concept of entry barriers implies that substantial costs, time and investment are required to enter an industry. The higher the entry barriers, the less likely are the new firms to enter the industry. Entry barriers depend on two sub-factors: ease of building supply, and ease of building demand.

Ease of building supply implies how easily new firms can build their primary activities, and depends on three factors:

Access to difficult-to-trade resources, capabilities, and core competencies. These may include new technology, scarce raw materials (e.g. diamond, crude oil), or assets (e.g. content that could be used to offer mobile services). For example, Gillette faced lower costs of entry into disposal lighters than many other firms, because of its well-developed distribution channels for razors and blades. Sometimes, requisite resources and capabilities may not be accessible at the time of entry, but need learning and experience to be accumulated. If experience can accumulate more rapidly for the later entrants, than for the existing pioneer firms, then the later entrants may have an entry advantage. They may observe the best of the pioneer processes, invest in latest technology, or adopt new methods, without being encumbered by the old ways and inertia that may beset the existing firms.

Reachable capital requirements. It is easier to build supply if the capital requirements are modest or within the reach of a new firm. Capital may be in form of funds for investment, or in other forms, such as the information technology infrastructure or the distribution channels. Business models may influence capital requirements, for instance, a new firm may be able to lease the IT infrastructure and outsource the distribution channels, instead of building them. Another factor to consider is Minimum Efficient Scale (MES), or the minimum scale of operation for being cost-effective. If the minimum efficient scale is relatively small compared to total market size (e.g. software applications), it is easier for the new firms to enter. But if it is large, then the industry structures tend to be more concentrated and it is more difficult for the new firms to build supply. For instance, Kanoria (2007) estimated that in the US airline industry, using the US Bureau of Transportation data from 1990 to 2005, MES was only eight aircrafts. Airlines achieved little cost savings by operating with greater number of aircrafts, as any savings were balanced by the higher costs of operational coordination. The low capital requirements for cost-effective operations attracted more than 100 airlines to the US skies. A final factor to consider is the economies of scale. Economies of scale exist when average total cost declines as output in a period increases, such as because of the possibility of specialized investments in machinery and human capital at higher volumes. For instance, in ball bearing manufacturing, production of less than 100 rings is done by hand on general purpose lathes at fairly high average costs. For 100 – 1 million rings, investments in a specialized screw machine allow moderate average costs. For more than 1 million rings, an even more specialized high speed, continuous process machine allows even lower average costs. Moreover, the average costs decline as the specialized machinery is operated at a scale close to full capacity.

Favorable regulatory policies, such as liberal, transparent, and easy licensing, tax breaks, and other support enable new firms to build new supply more effectively.

Ease of building demand implies how easily new firms may capture a share of the market, and also depends on three factors:

Penetrability of the customer relationships of existing firms, which is based on their reputation and brand loyalty, and knowledge of the customers about the firm’s products and their perceived distinctiveness. If the existing firms have strong reputation, brand loyalty, and other forms of product differentiation, and have invested in training their customers about their specialized products, and how they are distinctive, then it will be difficult for the new firms to win over these customers.

Insufficient switching costs from the existing products or services to ones offered by the new firms. Switching costs tend to be high when the firms operate as network exchanges, where the value accrued by a customer is a function of the size of the network – also referred to as the installed base. For instance, if all the friends of a customer are on facebook, then the customer may not perceive as much value from switching over to an alternative social media application where s/he has no friends currently. Switching costs also tend to be high when the firms operate as solutions shops, where the value accrued by a customer is a function of a set of complementary products and services offered by the firm as a single solution. For instance, if a customer has bought and gained expertise in Macromedia’s Flash suite on a regular desktop, then this customer may not be willing to switch over to Apple’s Macintosh since Apple’s products are not compatible with Flash.

Rapid market renewal, generating shifts in customer preferences and segments. An important factor influencing the pace of market renewal is product lifecycle. Product lifecycle is the evolution of a product through sequential stages of introduction, growth, maturity, and disruption. In fashion and technology-driven industries, product lifecycles tend to be very fast, resulting in rapid change in customer preferences and segments. New fashions and technologies disrupt the previous ones, opening a window of opportunity for the new firms who offer fresh fashions and disruptive technologies in their products and services. For instance, with rapid growth in downloadable music since mid-2000s, the sales of audiocassettes have disappeared, while that of the pre-recorded CDs has fallen sharply. Older fashions and technologies may still be attractive for alternative market segments, such as those including less affluent groups; thus opening a window of opportunity for the new firms who are better connected with these alternative segments.

Besides the entry barriers, potential threat to entry of new firms is also a function of how vigorously existing firms are expected to retaliate against entry. The retaliation is likely to be strong if the existing firms:

enjoy substantial resources and historical experience to fight back, including excess cash and unused borrowing capacity, adequate excess productive capacity to meet all likely future needs, or great leverage with distribution channels or customers;

experience high exit barriers, which may include great commitment to industry, or highly specialized and illiquid assets that have limited alternative use.

face slow industry growth, which limits the ability of the industry to absorb a new firm without depressing the sales and the financial performance of existing firms.

Despite the formidable barriers of entry and retaliation from existing firms, new firms are still able to enter most industries based on technology, product, or process innovations. The profit potential of the industries where new firms must bring substantial innovations to succeed is higher than of the industries where new firms may enter with limited or no innovations. Learning and experience factor, and resources, capabilities, and core competencies, do offer some protection to the existing firms; however, the same may also trap the existing firms into older paradigms. Instead of expending their resources in just retaliating against new firms, existing firms may also consider collaborating with or possibly acquiring the new firms, especially if they are genuinely innovative.

Threat of substitute providers. Substitutes limit the potential profits of an industry by placing a ceiling on the prices firms in the industry can charge. The more attractive the price-performance alternative offered by substitutes, the firmer the ceiling. Laptop manufacturers confronted with the large scale penetration of other portable devices such as tablets and smartphones are learning this lesson today, as have postal service firms that faced extreme competition from alternative, low-cost mail transmission substitutes such as the email. Substitutes limit profits in normal times, and the bonanza an industry can reap in boom times. High oil costs and extreme weather conditions are generating a huge demand for the solar-based device firms. However, the industry’s ability to raise prices is moderated by several energy substitutes, such as nuclear power, natural gas, energy insulation products, and energy conservation efforts.

To identify substitutes, firms need to search for other products that can perform the same function or fulfill the same need as the products of the industry. For instance, when the equity markets are performing poorly, equity brokers may find substitutes in the offerings of the real estate brokers, insurance brokers, foreign exchange brokers, commodity brokers, and private equity funds. The firms should be particularly attentive to those substitute products that (a) show a trend of improving their price-performance ratio, and/or (b) generate high profits, that may become the basis for the substitute providers to drive cost and price reduction or performance improvement and differentiation. For instance, electronic alarm systems are a strong substitute for the security guard industry. Their price-performance ratio has continuously improved, as labor-intensive guard services face cost escalation and more cost-effective and better performing electronic systems have been launched. The successful security guard firms are those who offered packages of guards and electronic systems, rather than to try to outcompete electronic systems. On the other hand, candles are a poor substitute for lightbulbs, even though both are lighting solutions. Candles offer limited light, and pose a higher risk of starting a fire.

The position of the firms relative to the substitute providers is generally a matter of collective action by the industry participants. Product quality improvement, product availability, and product differentiation and advertising by a single firm may not be sufficient to improve the industry’s position against a substitute. However, heavy and sustained efforts by all participating firms can improve the industry’s collection position. For instance, jute manufacturer association in India invest significant amount to promote jute as an ecologically-friendly packaging material, thereby bolstering jute against the substitutes such as plastic.

The executives must decide the dividing line between the firms who provide a substitute vs. the competitors. For instance, Subway competes with Panera Bread in the sandwich business, but full service restaurants such as at Hilton’s hotel will be a competitor if industry is conceived as the restaurant industry and a substitute otherwise. Of course, takeaway sandwich offered at a grocery store is likely to be considered a substitute, not a competitor.

Bargaining Power of Buyers. Powerful buyers bargain for higher quality or more services, lower prices, and play competitors against each other – thus putting pressure on industry profitability. An industry may serve several buyer groups, whose forcefulness to bargain depends on three factors:

Its need for superior terms of purchase, such as because of the low profitability of its industry, or because its purchases from our industry constitute a significant portion of its costs. For instance, auto firms in many nations pressure their suppliers to offer superior terms of purchase, because of the low profitability of the auto industry and high share of auto parts in the automaker costs. Conversely, buyer groups that are more profitable and that expend only a small share of their budget on the industry’s products are less sensitive to cost, are more considerate of the viability of their vendors, and are less likely to pressurize for better terms.

Its leverage over our industry, such as because of its knowledge about our industry, or its power to negotiate, and integrate backward into our industry. When a buyer group is knowledgeable about our industry’s demand patterns, cost structure, and price discrimination, then it is in a better position to secure the best terms and counter claims that the existing terms are the best possible ones. It can do so in two ways. First, if a buyer group is concentrated, and its purchases constitute a large share of our industry’s sales, then it will have greater power to negotiate with us. This is particularly so when our industry’s fixed costs are high, so that large volumes are critical to fill the capacity and secure economies of scale. For instance, consolidation of the department stores and retail chains has increased the power of these buyer groups, and put downward pressure on the margins of the ready-to-wear manufacturing industry that has a need to recover the high fixed costs of new fashion designs. Second, buyer group could use its knowledge to integrate backward into our industry, and to be credible, engage in partial self-production, referred to as tapered integration. For instance, General Motors and Ford are known for producing some of their needs for a given specialized component in-house, and purchasing the rest from outside suppliers.

Its ease of substitution, such as because the products offered by our industry are undifferentiated and standard, or because they do not involve much switching costs. When an industry’s products are undifferentiated and standard, buyer groups can easily play one firm against the other. Similarly, when an industry’s products do not lock-in the customers, buyer groups are more willing to go for the substitutes that offer marginally superior price-performance ratio. For instance, the older buyer groups who have devoted considerable time in learning about Microsoft operating system are less likely to switch over to Android and other alternatives, as compared to the younger buyer groups who are deciding which operating system to learn. Similarly, the older buyer groups that already have a game console are more likely to use these game consoles for smart applications such as navigating the internet and watching movies, than the newer buyer groups who may consider gaming as well as other functions on their smart televisions or smart tablets, or other devices.

The firms may improve their strategic position through their buyer group selection decisions. All industries typically have multiple buyer segments, each with different forcefulness to negotiate. For instance, replacement or aftermarket parts market is often less price-performance sensitive than the original equipment manufacturer (OEM) market.

Bargaining Power of Suppliers. Powerful suppliers bargain for higher prices or threaten reduced volumes and/or quality of purchased products – thus putting pressure on our industry’s profitability. An industry may deal with several supplier groups, whose forcefulness to bargain on factors that mirror those of buyer groups.

Its need for superior terms of sale, such as because of the low profitability of its industry, or because our industry’s purchases are not of great importance to it – such as because they constitute only a small portion of its overall revenues.

Its leverage over our industry, such as because of its knowledge about our industry, or its power to negotiate, and integrate forward into our industry. When a supplier group is knowledgeable about our industry’s sourcing patterns, cost structure, and demand conditions, it is in a better position to secure the best terms. It can do so in two ways. First, if a supplier group is concentrated, and its products are critical to our industry’s success, then it will have greater power to negotiate with us. Second, the supplier group could use its knowledge to integrate forward into our industry, and to be credible, engage in R&D for value-added processing.

Its difficulty of substitution, such as because the products it offers are proprietary and differentiated, or because they involve significant switching costs.

Note that the concept of suppliers includes not only the other firms providing intermediate inputs, equipment, and services, but also the labor. Scarce, highly skilled employees are difficult to substitute; they may have significant knowledge about our industry, as well as an ability to become potential new entrants. When the economy is in boom, or when the cost of living is increasing, labor may feel particular need for improved employment terms. Its leverage may be high if the firm is unable to find ways to expand its skilled labor pool. In order to improve its leverage, labor may take collective action, such as by forming unions.

Intensity of Rivalry among Competitors. Rivalry among competitors means jockeying for position, using tactics that include price competition (e.g. price wars, discount wars, or free gift wars) and non-price competition (e.g. advertising wars, product line wars, or warranty wars). When one firm takes an action to improve its position, other firms tend to notice effects on their own position and react with a countermove. Price reductions are easily and quickly matched by competitors, and result in a reduction in the revenues of the entire industry, unless the price elasticity of demand is sufficiently high. Non-price differentiators are more likely to help grow the industry demand, and have more asymmetric effect on participating firms, depending on their capabilities such as for advertising, introducing new product lines, and high accuracy to keep the warranty costs low. Intensity of rivalry among firms depends on the following three factors:

Presence of numerous, equally balanced, or diverse competitors. Intensity of rivalry is usually inversely correlated with the industry concentration ratio. Four-firm concentration ratio measures the share of the market for the top four firms, and is interpreted low and highly competitive if less than 50%, moderate if between 50 and 80%, and high if more than 80%. In the US, breakfast cereals, circus, and automotive manufacturing are highly concentrated. Flight training, sugar manufacturing, and fiber optic cables are moderately concentrated. Daily newspapers, truck driving schools, full-service restaurants, and legal services are less concentrated.

When there are numerous competitors, some may believe they could reduce prices and gain market share without being noticed by their rivals. This will keep the intensity of rivalry high. Even when there are only a few competitors, but they are equally balanced in their resources, capabilities and core competencies, they are likely to retaliate vigorously to any unilateral moves by their competitors in order to defend their share of the market. However, if these competitors are imbalanced, then the leader firm tends to act in a more disciplined manner and the non-dominant firms are also encouraged not to take any adverse actions.

Finally, if the competitors are very diverse in terms of their goals, historical or cultural origins, strategies, and tactics, they may not play by the same set of rules and perceive rivalry to be overwhelming. An example is the rivalry between Samsung – a Korean firm, and Apple – an American firm. Samsung pursued a strategy of offering a large variety of its smartphones at a range of prices, to be affordable to the emerging market customers, where it has gained a leadership position. In contrast, Apple strategy was to offer a limited variety of its smartphones at only a higher price range, to ensure a sense of pride and exclusivity for its customers. While it has maintained a leadership in the industrial markets, it had to give up leadership in terms of volumes to Samsung.

Disruptive growth of the industry. When an industry is growing slowly, or is in a mature or disruptive phase, firms are more likely to fight to keep their share of the market. In such markets, products of an industry tend to become like commodities, with low levels of differentiation. Therefore, they are prone to intense price competition, with little scope for any meaningful non-price differentiation. Pressures on the firms to engage in such competition tend to be higher when their fixed costs are high and they have excess capacity, so that they need to maintain and expand their share of the market to have a competitive cost structure. Pressures are also high when the firms have low value-added (price – cost of intermediate inputs), as then they need large volumes to recover their fixed costs. Finally, pressures are high when the storage costs of the products are high, as in the case of perishable products, so that the firms are motivated to try to dispose their products quickly and at whatever value they may be able to realize.

High exit barriers. Exit barriers are the factors that make firms reluctant to exit from the industry, because of their emotional commitments, cognitive stakes, economic costs, or regulatory sanctions. Executives may have emotional pride in an industry associated with their family and community. Or, they may have high cognitive stakes, such as when a diversified firm may not wish to exit a loss-incurring smartphone business because of the potential negative impact on its mobile software business, and a foreign firm like Samsung may not wish to exit the US smartphone market because it may consider it as a loss leader gateway for introducing other product lines in the US in future. Or, they may have to bear the economic costs to lay off labor, and their assets may have limited salvage value if sold. Or, the government may seek to discourage their exit because of the perceived effects on the local region or job losses, and may try to bail them out. All these factors contribute to firms retaining inefficient operations, and competing vigorously with the more efficient firms, thus intensifying the rivalry.

Firms may improve their position in competitive rivalry by focusing their efforts on the fastest growing segments of the industry, or on market areas where they have an asymmetric advantage in terms of resources and capabilities and being able to differentiate. They may also try to avoid confronting competitors with high exit barriers, so that they mitigate the threats of price warfare.

Exhibit 5.2 Facebook through the lens of Porter’s Five Forces

| Threat Of New Entrants: Moderate (3/5)

Threat Of Substitute Products: Moderately high (4/5)

Bargaining Power Of Customers: Moderately high (4/5)

Bargaining Power Of Suppliers: Moderately low (2/5)

Competitive Rivalry Within The Industry: Moderately high (4/5)

Overall, the structure of the social networking industry is moderately competitive (total of 17/25, i.e. 3.4/5). Source: Adapted from Forbes (2014) |

Strategizing based on Structural Analysis

Structural analysis of five forces helps to diagnose the causative factors influencing the profitability of an industry. It reveals the threats and the opportunities for improving a firm’s position. It also reveals strengths and weaknesses of a firm relative to other firms in the industry. Based on the structural analysis, a firm is able to craft a competitive strategy to create a defendable position against the five forces, using three possible approaches:

Better competitive positioning. A firm may assume the structure of the industry as given, and seek to find and move into positions or segments in the industry where the five competitive forces are the weakest. These may include faster growing segments of the industry, targeting buyer groups and mobilizing supplier groups less prone to bargain, addressing needs not so vulnerable to substitutes, and leveraging experiences for reconfiguring capabilities to avoid being jeopardized by potential new firms.

Influencing the balance of forces. A firm may consider what aspects of the five competitive forces are under its control, and strive to actively shift the forces by managing those aspects. It may, for instance, improve its product differentiation, and knowledge of the customer and supplier industries; it may integrate backward or forward to reduce its vulnerability; or it may make new capital investments to preempt the entry of new firms.

Exploiting evolution and disruptions in industry structure. Just like product life cycle, industries also experience the familiar S-curve life cycle. The cycle moves the industry from an emerging stage, to growth stage, to maturity, and then to decline and disruption. Industry evolution and disruption motivates changes in the structure of competitive forces as well. For instance, during the emerging and growth phase, firms tend to focus on specialized and narrow set of activities, to maintain their agility and growth. But in the maturity phase, they tend to integrate vertically, backward as well as forward, in order to maintain fuller control over their operations, and to gain new avenues for growth. That raises the capital requirements, and increases the barriers to entry. In the disruption phase, extensive vertical integration may become a liability, and inhibit the ability of the firms to exit from the older paradigms and to reconfigure their assets around new technologies and markets. Predicting the likely shifts in the structure of competitive forces through the different phases of industry evolution can help firms stay ahead.

Competitive Positioning using Strategic Groups Analysis

An important goal of the structural analysis is to improve the competitive positioning of a firm in the larger value system of the industry. In most industries, there exist multiple possibilities of competitive positioning, also referred to strategic posture. Different groups of firms tend to adopt different strategic postures, each characterized by a different cluster of competitive strategies and tactics, targeting different buyer groups, mobilizing different supplier groups, addressing different set of needs relative to substitutes, and investing in different process configurations. A group of firms that exhibit similar strategic behavior, but whose behavior is dissimilar from other firms, is referred to as a Strategic Group. The firms within a strategic group perceive each other as their most direct competitors. Strategic group hypothesis asserts that within an industry, firms with similar process configurations will pursue similar competitive strategies with similar performance results. The Strategic Group concept has been found to explain performance differences within an industry in various studies.

Understanding the nature of strategic groups within an industry is important for three reasons (Ketchen & Short, 2012).

The other members of a group are often the best referents for executives to consider for assessing performance and considering strategic moves. Members of other groups are often not as relevant. Subway, for example, does not compete for customers with firms in other strategic groups of the restaurant industry, such as Ruth’s Chris Steak House and P. F. Chang’s. Subway has little interest in offering a gourmet steak or the experience offered by fine-dining outlets.

The strategies pursued by firms within other strategic groups highlight alternative paths to success, and could offer learning insights to a firm. During the recession of the late 2000s, midquality restaurant chains such as Applebee’s and Chili’s used a variety of promotions such as coupons and meal combinations to try to attract budget-conscious consumers. They adopted these ideas from the operating models of firms in other strategic groups such as Subway and Quiznos that already offered low-priced meals and were not impacted by the recession.

Third, the analysis of strategic groups can reveal gaps in the industry that represent untapped opportunities. Within the restaurant business, for example, few national chains in the U.S. offer both very high-quality meals and a very diverse menu. One exception is the Cheesecake Factory, a chain of approximately 150 outlets whose menu includes more than 200 lunch, dinner, and dessert items.

Identifying Strategic Groups

To distinguish between strategic groups within a sector and to analyze the differences in their behavior, one starts by identifying key strategic variables that influence the behavior of firms in that sector. Key strategic variables might include two or more variables from the following types of measures: (1) generic strategy measures, such as cost structure, product variety differentiation, and geographical or customer segmentation (focus or broad), (2) corporate strategy measures, such as vertical and horizontal integration, and scale of operations (3) governance strategy measures, such as ownership structure, social enterprise, green sensitivity, strategic emphasis on innovation, and strategic emphasis on gender and inclusion, (4) functional strategy measures, such as manpower skills, R&D capability, automation, and marketing and sales factors, and (5) organizational measures, such as length or depth of experience, planning intensity, and perception of the industry as stable or dynamic. Altuntas, Rauch & Wende (2014) suggest using two set of factors that are associated with the acquisition of competitive advantage -: (1) factors that capture the scope commitment of the firms’ operation, such as variable related to the firm’s product diversity, market segments served, and the firm’s size, and (2) factors that deal with the firm’s resource commitment, such as variables related to distribution methods and investment or financing strategies.

The simplest strategic grouping is based on the identification of two key variables that generate differing behaviors of firms in a sector, and mapping the firms on a 2x2 map using these variables. The firms which are closest to each other are then classified into a strategic group. The market share of each firm can be illustrated by the size of the circles. A 2x2 strategic group mapping is easy and simple, and does not require huge data. However, one requires deep industry knowledge to identify the two most important variables; in practice, different strategic groups might be generated using different set of variables. For instance, in the US restaurant industry, breadth of menu and perceived quality are two key variables. Based on this, Ketchen & Short (2012) identify six strategic groups illustrated in Exhibit 5.3.

Exhibit 5.3: 2x2 Strategic Group in the U.S. Restaurant Industry

| High Perceived quality | Ruth’s Chris Steakhouse Benihana P.F. Cheng’s | |||

| Jimmy John’s Subway Quiznos | Applebee’s Chili’s | |||

| Kentucky fried chicken Popeye’s Pizza Hutt | Burger King Jack in the Box McDonald’s | Cracker Barrel Denny’s | ||

| Low | Breadth of menu Low High | |||

Source: Adapted from Ketchen & Short (2012)

A more complex strategic grouping is based on the use of cluster analysis to classify a sample of firms into different groups. In this approach, multiple strategic variables may be used as the criteria for identifying clusters. The cluster analysis may be used either to authenticate one or more a priori typologies of groups, or to develop an empirically identifiable typology. An illustration of the latter approach is given in Exhibit 5.4.

Exhibit 5.4 Developing Strategic Groups Using an Empirical Approach.

| Johnson et al (2011) conducted a study to profile strategic groups of firms in the US food manufacturing industry. They surveyed 4,341 food manufacturing firms from across the U.S, using a random sample from a national database. They received complete responses from 324 firms. The survey included several variables known to influence the behavior of firms in the food industry. All variables were measured using well established scales, mostly on a five point scale (1 = Not at all, 5 =To an extreme extent). The log-likelihood estimation process indicated presence of three clusters of firms, based on the above measures. The first cluster comprised of about 50% of the firms, and the other two comprised of roughly 25% each. The authors then compared the means scores of various measures across the three clusters. The three clusters differed from one another on three of the measures: planning, overall least cost, and product differentiation. Cluster 2 had the lowest score on planning, overall least cost and product differentiation. Cluster 1 had the highest score on product differentiation. Cluster 3 had the highest score on planning and overall least cost. All three clusters put strong emphasis on customer satisfaction. The data showed that Cluster 1 comprised of younger firms offering innovative products, termed ‘the differentiators”. Cluster 2 comprised of smaller, low performing firms operating in fringe segments, characterized as ‘the lifestylers’. Cluster 3 comprised of highest performing, older, larger firms, concerned with both cost and scale, characterized as ‘the performers’. Each group faces unique risks and available exit strategies. The differentiators face the risks of inadequate resources and cash flows to sustain survival and growth; their exit strategy is often to sell out to the performers. The lifestylers face risks of disruptive change from the innovative differentiators; their exit strategy is often to transfer the business to the next generation of more innovative entrepreneurs, or be taken over and restructured by the performers. The performers face the risk of cut-throat rivalry and commodification; their exit strategy is generally to consolidate with other performers or with an ambitious differentiator. Source: Adapted from Johnson, Johnson, Devadossc & Foltzd (2011) |

Steps in Strategic Group Analysis

Strategic group analysis typically involves the following three steps.

Evaluate the strength of mobility barriers that prevent the firms in one group from competing with the firms in another group. Mobility barriers are group-specific entry barriers – they limit rapid learning from the successful strategies of firms that belong to particular strategic groups.

Conduct a five forces analysis for each strategic group, and compare the strategic groups on the strength of each force.

Identify appropriate strategic responses, including (a) strengthen the existing group or the firm’s position within that group, (b) move to a better strategic group, (c) move to another strategic group and strengthen that, or (d) create a new strategic group. This entails identifying innovative ways to overcome the barriers to learning from the successful strategies of firms in other strategic groups, and/or create strategies to situate the firm into another strategic group. The firms develop understanding of the industry evolution dynamics, and of their capabilities, risk preferences, and available opportunities to meet the challenges of this dynamics.

With regards to the last step, changing at will between strategic groups can be difficult due to the existence of mobility barriers. Studies find a low level of inter industry movements and thus a low degree of Strategic Group dynamics (Mascarenhas, 1989). This is attributed to the similarity of firms within a strategic group with regard to their skills, capabilities and assumptions about the future. Due to this similarity, firms tend to anticipate each other’s reaction very precisely and evolve similarly over time (Porter, 1980). Nevertheless, the composition of strategic groups can vary over time, i.e. firms might leave one Strategic Group and join another one. The changes in the strategic group composition may be driven by external or internal forces. Externally, changes in macro environment can lead to misalignment between a firm and its environment, and reduce the effectiveness of its current strategy (Porter, 1980). As the firms try to adapt to macro environmental developments, the firm might change its strategy as the bases of competitive advantage change (Herget, 1983). Internally, firms may be motivated to search for new domains and access new resources, which could move them into another strategic group (Mascarenhas, 1989). Exhibit 5.5 illustrates the dynamic evolution of strategic groups in the Korean small and medium-sized electronic parts industry.

| Exhibit 5.5. Evolution of Strategic Groups in Korean Electronic Parts Industry Kim and Ha (2013) used dynamic strategic group analysis to analyze changes in the performance of 102 small and medium sized Korean electronic parts firms and their decisions to change their strategic groups, in response to five major environmental changes from 1990 to 2001. First, the IT boom after the introduction of Windows in 1995 and ecommerce resulted in a growth environment, followed by a decline after 2000 because of the dotcom bust. Second, the wage inflation eroded the competitiveness of Korean firms, and made them vulnerable to low cost Chinese competition. Third, there were opportunities for establishing Chinese factories and for catering to Chinese demand. Fourth, digitalization resulted in modularization and integration of several parts into high-quality technology-intensive integrated circuits, alongside shortened product lifecycles. Fifth, the Asian financial crisis of 1997 hurt the financially weaker companies. Kim and Ha (2013) used factor analysis to identify four dominant strategy variables – product breadth, market breadth, innovation capability, and production capability. The cluster analysis using these four variables revealed four strategic groups. (1) subcontractor group, comprising of small, less experienced firms with low product and market breadths, and low innovation and production capabilities. This group had the least return on sales performance, and the Asian financial crisis significantly reduced the number of firms in this strategic group from 40 before 1997 to 23 after 1997. A few of the firms moved to another strategic group, and were able to improve their return on sales performance. About a third of the firms in this group did not move and died. Significantly, firms in other groups were not attracted to this group. (2) innovator group, comprising of the firms in the newer IT sectors who targeted global markets, and showed strong innovation and production capabilities. This group had the best return on sales performance, but the number of firms in this group gradually decreased from 1990 to 2001, because of the shortening product lifecycles. The firms from this group had low mortality rates; and lower performing members of this group were able to survive by moving to other groups. Firms in other groups were unable to move into this group. (3) diversified group, comprising of firms with broad product and market portfolio, but modest innovation and production capabilities. The number of these firms declined by more than 50% over the period and took strong hit from the 1997 financial crisis, because of the stretching of resources too thin. About a third of the firms in this group died, many others moved to another group. (4) focused producers, who specialized in limited product lines, with strong production capability but weak innovation capability. This group enjoyed strong return on sales during the early 1990s, but their advantage disappeared by the late 1990s, as the costs rose and Chinese competition intensified. About a third of the firms in this group also died, while many others moved to another group. By the late 1990s, a new fifth strategic group emerged, as those moving out of the diversified group restructured and reduced their product lines, and those moving out of focused producer group broadened their customer base worldwide and developed Chinese production bases. This new strategic group was of ‘global marketers’, who targeted a broad group of customers, using limited product lines. Source: Adapted from Kim and Ha (2013) |

Process Approach: Zero-sum vs. Positive-sum

The structural approach to macro-environment emphasizes the attractiveness of specific market structures, and the strategies that might be available to firms for accessing the more attractive segments and developing sustainable positions. The process approach recognizes that the firms may not be homogenous in recognizing and pursuing specific set of strategies. The strategy set for each firm may vary as a function of the process of ownership, exchange, and governance that it perceives and experiences. Ownership refers to who owns the value. Exchange refers to what value is created through inter-firm relationships. Governance refers to the criteria that guide how value is distributed or captured among different firms.

One of the major criticisms of the structural approach is its assumption that the process of ownership, exchange and governance for accruing value in any industry is based entirely on a zero-sum perspective. A zero-sum perspective implies that the overall size of value available for the firms to capture is constant. For a firm to improve its performance, it must find ways to own most of the value (such as through vertical or horizontal integration), or to gain control of the governance so that it is able to capture most of the value. The process of exchange does not create any value; rather it is only a means for distributing value. Therefore, if the firms holding a zero-sum perspective wish to improve their performance, they must seek to finds ways to reduce the share of other players, such as by limiting potential entrants, limiting the power of its customers and suppliers, limiting the risks of substitutes, and limiting the share of its rivals.

In practice, the process of ownership, exchange and governance has a positive sum component also. A firm may not be able to enjoy the greatest and most sustainable profitability and strategic advantage if it monopolizes on bargaining with its suppliers and customers, and on excluding existing and potential rivals and substitutes. On the contrary, such monopolization may impede change and progress in the industry. It may alienate both suppliers and customers, and encourage potential rivals and substitutes to target alternative markets. As a result, even though a firm might continue to keep a tight hold on an industry, the value and the need for this industry or segment of the industry may itself vanish. Exhibit 5.6 illustrates the case of Kodak, where once strong industry position failed to guarantee sustainable advantage.

| Exhibit 5.6 How Phone Industry Marked the last Kodak moment? Founded in 1880, the New York-based Eastman Kodak was the Google of its day. In 1976, it accounted for 90% of film and 85% of camera sales in America. Thereafter, it began losing that grip, after it built one of the first digital cameras in 1975. Until the 1990s, it consistently rated as the world’s five most valuable brands. It also operated a business model that was ripe for disruption by the substitutes and the customers. Kodak’s business model was to sell cheap cameras and to make money when customers bought expensive film rolls. By the 1990s, digital photography replaced film, and in the 2000s, smartphones replaced cameras. Kodak’s revenues fell from a peak of $16 billion in 1996 to $6.2 billion in 2011. The share price fell nearly 90% in 2011, with market capitalization of only $220 million. The profits fell from a peak of $2.5 billion in 1999 to losses in 2010s, forcing it to file Chapter 11 bankruptcy in 2012. The employee base fell from a peak of 145,000 worldwide in 1988 to just 8,800 at the end of 2013 when it came out of its bankruptcy. Kodak had a strategy of hefty investment in research, a rigorous approach to manufacturing and good relations with its local community, yet it was unable to adapt as the margins slipped from 70% in the film business to less than 5% in the digital business. It briefly aspired to transform into a profitable pharmaceutical firm, striving to turn the thousands of chemicals created by its researchers for use in film into drugs. But that effort was unsuccessful, and ended in the 1990s. Kodak thought that it will be able to sell loads of films in the emerging markets, such as to the fast growing Chinese middle-class. However, the Chinese consumers decided to leapfrog from no cameras to digital cameras, and quickly to smartphones, much faster than the customers in the US and other developed nations. In the 1990s, Kodak decided to focus back on its imaging core competency. It staked claim for dominance in the digital camera business by allowing consumers to post and share their photos online. That proved to be a successful strategy for a few years, until the camera phones killed the digital camera business. In the 2000s, Kodak invested its cash reserves to buy several ready-made businesses in the digital business, but none of these were successful as the digital was no longer a big opportunity. After about 125 years Kodak is poised, like an old photo, to fade away. Now it is no longer the photography giant whose name once splashed across the Olympics and television ads. It’s a smaller firm, focused on digital printing, under the leadership of Antonio Perez, who took charge in 2005 and was previously at Hewlett-Packard – a leader in the print business. Having lost its photography and camera business entirely, Kodak in 2013 signed a licensing agreement with California-based JK Imaging permitting the use of Kodak name of various digital cameras and pocket video cameras. Source: Adapted from The Economist (2012) |

A Firm’s Value Net and the Positive-sum Process

When the process of ownership, exchange, and governance is viewed from a positive-sum perspective, it becomes important for the firms to cultivate and respect the power of suppliers and customers, and of the existing and potential rivals and substitutes. Strong, dynamic suppliers, customers, rivals and substitutes become the basis for strong complementor networks. These networks tremendously expand the resources and capabilities that a firm has access to, in terms of cost-effectiveness, specificity, variety, innovativeness, as well as responsiveness. They thus dramatically improve the capacity of the firms to offer innovative value, using a stream of creative solutions and exchange linkages. Positive-sum value linkages could encompass many and all different participants who influence the generation and sustainability of value in a market sector. Exhibit 5.7 illustrates the case of Fuji and how it used a new value net to sustain growth.

| Exhibit 5.7. How a New Value Net Sustained the Fuji’s March? Like Kodak in the US, Fujifilm enjoyed near monopoly of film and camera business in Japan and was an archrival of Kodak. Unlike Kodak, Fujifilm has been able to transform itself into a new profitable business, with a market capitalization of about $15 billion in 2014. Seeing the signs of digital boom as early as the 1980s, Fujifilm developed a three-pronged strategy: to squeeze as much money out of its traditional film value net as possible, to prepare for the switch to digital and to develop new business lines. Shigeta Komori, Fujifilm’s boss between 2000 and 2003, invested about $9 billion on 40 companies that were involved in complementary value nets. Simultaneously, he invested about $3.3 billion in restructuring the business model to prepare for the switch to digital, and to eliminate business distributors, development labs, managers and researchers engaged in its traditional film value net. Fujifilm recognized that just as films are preserved with anti-oxidants, cosmetic firms also look for preserving skin with anti-oxidants. In searched its library of 200,000 chemical compounds to identify 4,000 that were related to anti-oxidants. With them it launched a highly successful line of cosmetics, called Astalift. It also applied its expertise to new types of films, such as making optical films for expanding the viewing angle of LCD flat-panel screens where it invested $4 billion in the decade of 2000 and held a 100% market share in early 2010s. Even as the traditional films went from 60% of Fujifilm’s profits in 2000 to nearly nil by 2010s, its new found sources of revenues have sustained the progress of Fujifilm. Source: Adapted from The Economist (2012) |

Brandenburger and Nalebuff’s (1997) Value Net underscores the potential of creating new value at the firm-level through positive-sum value linkages. As shown in Exhibit 5.8, the Value Net model comprises of five factors – the firm, the suppliers, the customers, the substitutes, and the complementors. In contrast to the Porter’s five forces model, the value net model emphasizes complementors instead of competitors. Relations with complementors arise because customers have other suppliers and suppliers have other customers.

Exhibit 5.8 The Value Net

Another supplier in an industry is a complementor if customers have a higher value for a firm’s products if they also have that supplier’s product or service. For instance, consider 3D Systems -- a leader in 3D printing technology; it pioneered stereolithography method of rapid prototyping in 1986. The 3D printing saves time, cost and efforts during the manufacturing process and improves the quality of output. Taro Technologies, on the other hand, is a leader in 3D scanning. The 3D scanning is a process in which three-dimensional attributes of an object are captured along with information such as color and texture. Taro Technologies is a complementor to 3D systems. While the cost of 3D scanners remains high for wider adoption, yet, improvements and reduced prices of 3D scanners has allowed 3D printers to rapidly redefine the traditional manufacturing value chain from simple make-to-stock to complex, engineer-to-order production strategies in aerospace, defense, automotive, healthcare and entertainment industries. 3D printing is allowing users to print silicone, latex, ceramic, clay, play dough, Nutella, or icing sugar. In the medical field, 3D printers are printing replacement body parts, organs, skin and bones. In China, a company used large 3D printers to build 10 detached single-storey houses in just a day (Magrina, 2014).

Conversely, another supplier in the industry is a competitor if customers have a lower value for a firm’s products if they also have that supplier’s products. Stratasys is a competitor for 3D systems, and is also a leader in 3D printing technology; it pioneered fused deposition modeling process of rapid prototyping in 1992. However, since 3D printing is still a fast growing nascent market, there is enough potential for the leading firms to not compete head-to-head. Thus, while the incumbent 3D systems chose to focus on the consumer printing industry, Stratasys has largely focused on manufacturers. Both the companies have roughly the same 2014 revenues: about $750 million (McKenna, 2014). Stratasys could be a formidable competitor for the 3D systems in future. In June 2013, Stratasys acquired MakerBot, which makes desktop 3D printers, which are relatively affordable and designed for personal use or small scale manufacturing. A MakerBot Replicator Mini was priced at just $1,375 in 2014 (Sharf, 2014).

A competitor firm may also be a complementor to some extent; similarly, a complementor firm may also be a competitor to some extent. 3D systems does offer a line of 3D scanners, that compete with the products of Taro technologies. This makes Taro technologies a competitor also of 3D systems. Conversely, while 3D systems and Stratasys compete for customers for their 3D printers, firms like Taro Technologies are more likely to invest in improving and reducing the cost of 3D scanner technology, if there are many different types of 3D printers available attracting many different types of customers. That makes Stratasys an indirect complementor of 3D systems.

An important weakness of Porter’s five forces model is that it views all other firms as threats to profitability of a firm. In reality, other firms can also facilitate overall growth of the industry as well as of the firm, because they all face the same suppliers, customers, technology and regulatory context. For instance,

Competitors who help set technology standards may create conditions for faster growth of the industry and the firm. ASTM International (Formerly, American Society for Testing and Materials) is an association of technical experts and professionals, including those working in 3D printing firms around the world. These firms have come together to establish several technology standards pertaining to the properties of 3D printing powders, and 3D printing mechanical parts, to facilitate the use of 3D printing in industries that require more accurate predictions of the output, and to promote greater confidence among the industrial and consumer users (Grunewald, 2014).

Competitors may also help the cause of a firm by advocating for favorable regulatory changes. 3D printed guns have given rise to the public safety and security risks. 3D printed foods have health-related risks. 3D printing of body parts or organs has ethical risks. 3D printing in general has many intellectual property risks. Also, access to the materials and parts for these different applications of 3D printing may be important for social security and health across nations. Competitors in the 3D printing industry have an important role to self-regulate standards for parts, processes, and safety, in order to mitigate risks and to guide the development of appropriate regulatory framework.

Finally, competitors may undertake complementary efforts to advance technology, in terms of cost, applications, and product quality. One such effort is the recent emergence of 4D printing, which adds the concept of ‘self-assembly’ to the 3D printed parts and components without human interaction. An example includes water pipes that can assemble themselves and adapt to changes in water pressure and temperature. The 4D printing addresses one of the major limitations of the 3D printing – that the assembly of 3D printed parts is complex and time consuming. The 4D printing should stimulate the overall demand for 3D printers and related materials and services.

The Value Net model encourages executives to think in terms of competition and cooperation – referred to as co-opetition, instead of simply considering other firms as competitors. The profit of any firm in the Value Net is the surplus in the value net with that firm less the surplus without that firm. Co-opetition offers a way for the firms to shape the game they play, instead of just shaping the game they find. It allows them to create new value through complementary linkages, and instead of just striving to capture available value from the hands of the other players.

There are three major steps for effectively using the Value Net Strategy. These steps comprise of a set of questions around three areas: players, added value, and rules of game.

Players questions

Identify the opportunities for cooperation and competition in a firm’s relationships with customers and suppliers, complementors and competitors.

Identify the potential for changing the group of players, and the type of new players a firm should bring into the game.

Identify the winners and losers from your presence in the value net.

Added value questions

Identify the added value of the firm.

Identify potential for increasing the added value of the firm, such as by improving the strength of cooperative relationships in terms of customer and supplier loyalty.

Identify the added value of other players, and how growth or decline in the value added of other players will influence the value net and the firm’s own value added.

Rules of the game questions

Identify the rules of the game that are hurting or helping the firm.

Identify the new rules / changes in the rules that will help the value net and the firm, and how to establish these rules through new contracts with other players

Identify the power of the firm and of other players for establishing new rules, and for rejecting or overthrowing those rules.

The Value Net model portrays relations in an industry from the perspective of a focal firm. Each type of firm in the Value Net has its own relations and its own Value Net, which is captured only partly in one firm’s Value Net. For instance, most of the industrial customers of Stratasys are not part of the Value Net of 3D systems, because the 3D systems is focused more on the consumer market. Similarly, most of the suppliers for Taro Technologies are not part of the Value Net of 3D systems, because those suppliers specialize in the parts and services for 3D scanners, and not 3D printers, and 3D systems has only limited presence in 3D scanners.

When the Value Net of a firm is extended to include the Value Nets of various other firms, then such value system makes it possible to examine the broader network of inter-business relationships within which a firm is embedded. Firms exist and persist because they are able to choose their relations, and are chosen by others for their relationships. Kanter (1994) referred this dimension of competition as “collaborative advantage’. A firm’s ability to offer competitive customer advantage depends in part on the resources and knowledge it is able to develop and access through its relations and networks. A firm competes to develop relations with the same or different cooperators, such as suppliers, distributors, complementors, and even competitors. A firm’s ability to develop collaborative relationships depends on the competitive advantages it is able to provide. Successful firms tend to attract more collaborators than the less successful ones. Different types of successful firms in a system of value nets give rise to a dynamic business eco-system, where the activities, skills, resources, and outputs of various firms specializing in different areas are accessed, combined, recombined, and coordinated, and where innovation, learning, and knowledge development take place ((Wilkinson, 2008). Porter’s national competitive advantage diamond is a tool for understanding these macro level positive sum process, and the implications for the strategic behavior of the firms.

A Nation’s Competitive Advantage Diamond and the Positive-sum process

The process of ownership, exchange, and governance is not entirely a matter of firm’s perception or cognitive beliefs. Institutionalized rules also contribute to differences in these processes across different nations and regions. Institutionalized rules refer to the conditions established because of the role of the government, and the role of chance and of history, traditions and culture. In some regions, institutionalized rules contribute to strengthening of the factor endowments, the related and supporting industries, the demand conditions, and the organizational profile of the firms within a sector. In these regions, relationships among firms and various players in their regional sectoral environment tend to be synergistic, and this synergy contributes to their collective strategic advantage. These firms are better able to withstand global competition, and become formidable regional and global players. They are also better able to develop competitive, growing, and sustainable scale, scope, as well as skills within their industry segments. Porter’s (1990) National Competitive Advantage Diamond is a popular tool for the firms seeking to adapt to and shape macro business eco-systems.

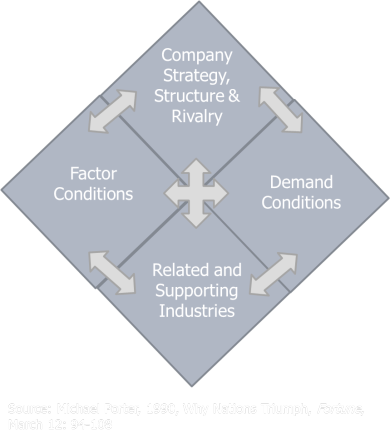

Porter (1990) conducted a ten country study of 100 key industries (excluding natural resource industries). The study investigated the rise, growth, international success, and erosion over time of this success of countries in these industries. Porter identified a Diamond model (see Exhibit 5.9), comprising of four elements:

Factor Conditions – the presence of key factors of production such as skilled labor, access to technology, or infrastructure

Demand Conditions – the domestic market demand for an industry’s products or services

Related and Supporting Industries – domestically available supply and distribution chain industries or related industries that are internationally competitive

Firm Rivalry, Structure and Strategies – the cultural organization and management of businesses in the industry, and national policies governing these businesses.

Exhibit 5.9: Porter’s Diamond Framework for National Competitive Advantage

Porter also recognized the role of chance and of factor disadvantages as additional fifth and sixth elements. Chance captures dramatic unforeseen events, such as major breakthrough inventions and technologies, major change in world demand, major shift in consumption preferences, major foreign political decisions or changes in government or failures in government (economic and/or political), major changes in exchange rate, major price shocks, and major regional or national wars. Factor disadvantages capture a significant lack of certain national resources, which require and inspire firms to innovate and upgrade skills and assets to compete. Nations with an abundance of a resource, such as low-cost labor in India and China, may not be innovative about that resource, hindering the long-term advantage internationally. In contrast, Japan addressed the disadvantages of limited space and labor by innovatively creating just-in-time manufacturing and highly-automated, flexible manufacturing lines.

Porter noted that the four key elements in the diamond play a limited role by themselves. Factor endowments, such as labor, raw materials, capital, and infrastructure, influence the cost of inputs and resources; while large home market and large rival firms potentially contribute to economies of scale. However, globalization and technology limit the gains of competing on input costs or on scale economies. Therefore, sustained national competitive advantage results from the capability to improve and innovate, not static advantages. Porter emphasized the role of spatial proximity in allowing each of the four elements to operate in a mutually reinforcing way to sustain this capability to improve and innovate. In particular, spatial proximity fosters cultural and social proximity, which facilitates the flow and exchange of information among firms about needs, techniques, technologies and strategies. Porter suggested four strategies for fostering positive-sum processes for national competitive advantage:

Specialized, efficient and quality factor inputs should be ensured and upgraded through training.

A core group of demanding local customers should be nurtured in specialized segments, whose needs anticipate those in the region and elsewhere.

A critical mass of capable local suppliers should be developed in a range of connected—instead of isolated—industries.

A local context should be forged that encourages upgrading and sustained investment and enables vigorous competition among a group of local rivals.

Exhibit 5.10 illustrates how Terviva, a US-based firm that develops new crops for regenerating unproductive farm lands, has used the diamond analysis to bet on a new sustainable biofuel crop – pangomia, for its huge clean energy potential.

Exhibit 5.10. Terviva uses diamond analysis to bet on a new biofuel crop

| Pongamia seed oil is excellent for biofuel, and the seed cake is usable as natural fertilizer or animal feed. Pongamia’s advantage is that it can produce 8X more than soybeans per acre, using less water and fertilizers than most other crops. Pongamia is being promoted in developing countries as suitable for smallholder cultivation, but the diamond analysis points to strong competitive advantage potential for the U.S. firms as well. Demand Conditions: During the decade of 2000s, more than 450,000 acres of citrus came out of production, because of the falling demand for orange juice and higher production costs. Therefore, many agricultural communities are looking for alternative new crops like pongamia. The U.S. enjoys very strong demand for sustainable, domestic sources of energy. This demand is driving innovation and capital formation in clean energy. Factor Conditions: Pongamia allows recovery of millions of acres of marginal and/or underproductive land in the U.S. including diseased citrus land, mined land and pasture land. This makes the U.S. is an ideal setting for scaled plantations of pongamia. Pongamia leverages existing agriculture infrastructure, in terms of distribution networks, equipment, advancements in agronomy practices, and a highly skilled agricultural labor force. Pongamia can be cultivated using existing fruit/nut tree equipment and oilseed processing infrastructure in the U.S. Other new biomass crops such as switchgrass and miscanthus cannot be processed using conventional equipment and require new and expensive bio-refining infrastructure. Moreover, there are billions of gallons of existing refining capacity throughout the U.S. that can convert pongamia’s vegetable oil in to biodiesel and renewable diesel without additional capital expenditure.

Firm Rivalry, Structure and Strategy: The U.S. government offers several incentives to the rivals in the energy industry to innovate and collaborate in order to reduce U.S. reliance on foreign oil. Related and Supporting Industries: Several U.S.-based academic institutions have committed to support innovations in pongamia in collaboration with the corporations. UC Davis and Texas A&M are engaged in pongamia genomics and co-product development. Commercial greenhouses and plant propagators are working with the pongamia seed firms to develop techniques to optimize the clonal propagation of pongamia, thus avoiding the need to build expensive large scale nurseries. Several financial institutions are also providing special grants and funds for new energy crops, such as pongamia. Source: Adapted from Rani (2013). |

Since 1990, increasing globalization and disaggregation of the value chains have allowed multinational enterprises to disperse their value linkages around the world. Porter (1990) held that these multinational enterprises are strongly influenced by the home base, and can have, “one true home base for each distinct business or segment” (Porter, 1990, p. 606). Many others have found that the multinational enterprises are often influenced by each unique country environment in which they operate and modify their strategies accordingly. Porter (1990) also held that the external enterprises can at best occasionally ‘‘seed’’ a cluster, but the indigenous players are critical for upgrading and sustaining the competitive advantage (Porter, 1990, p. 679). Others have found that this may not be true, particularly for the smaller nations. The Irish studies, for instance, showed how Ireland developed competitive clusters in the areas of semiconductors, computers and other electronics, and in healthcare products and pharmaceuticals, which were all based on the activities of the foreign firms (Clancy et al, 2001). These alternative studies are described as the neo-diamond perspective (Gupta and Subramanian, 2008).