Growth Strategy

Chapter 4

Value Strategies for the New Economy

| Exhibit 4.x Value Strategies for the New Economy Castrol, the world’s leading lubricants company, had a problem. As part of its differentiation efforts, Castrol had segmented its market by major clusters of business applications - cement, sugar, pulp and paper, textile, food and beverage, wood, mining, and glass. However, its business was now becoming commoditized. Castrol found that within each cluster, it had different types of customers having different attitudes towards how much they wished to engage with it. Broadly, its customers could be grouped into three tiers, based on their attitudes towards engagement with Castrol. (1) Tier 1: productivity-conscious customers, seeking to enhance productivity, lower costs, and grow sales. (2) Tier 2: cost-conscious customers, seeking to lower their total costs of operations. (3) Tier 3: price-conscious customers, seeking to shop for suppliers with lowest prices. How should Castrol adapt its strategy to better target different tiers of customers? For Tier 1 customers, Castrol developed a new personalized pre- and post- sales customer engagement process. The process begins with joint dialog between the Castrol and the customer teams, and a survey of the customer plant-specific personalizations needed in the generic plant platform. Metrics for tracking customer’s return on investments are established, and personalized package of solutions comprising of products and services is developed to realize the expected returns. Previously, only the customers performed the task of diagnosing the plant-specific needs, building the solution, and tracking the performance. As Castrol integrated this function to build long-term contracts based on trust, learning, and accountability, it was able to decommoditize its products. For Tier 2 customers, Castrol offered customized solutions based on a combination of its products and services. It provided documented case studies demonstrating how these products and services were most appropriate for specific types of plant conditions. It thus built credibility and confidence with these customers. For Tier 3 customers, Castrol automated the sales and delivery processes, to simplify and speed up the customer process of ordering its products and services. It reassigned its sales processing team to service the first tier of customers, and reduced prices for the third tier customers. Source: Adapted from Hax (2002) |

We are now in the age of new economy. In the new economy, the environment is volatile, uncertain, chaotic, and ambiguous. It is difficult and risky for the firms to rely on its past resources, capabilities and core competencies. Successful firms in the new economy know how to leverage not only their own strengths, but also the strengths of others. In other words, they know how to leverage differences for collective benefits. The work of several scholars (Fjeldstad and Stabell, 1998; Hax, 2002) shows that in the new economy, traditional value chains have evolved into three distinct forms of value strategies:

Product stream positions: Firms have several product stream positions; each stream has its own business-level strategy. Product stream positions allow a firm to develop a portfolio of products, which improves the economics of its operations. (Why? – due to the economies of scale, scope and experience). However, as more and more firms in an industry grow product stream positions, they experience a rising rivalry and race to manage the speed and cost of development of the product portfolio.

Custom solutions integrators: Firms integrate internal and external resources to design integrative custom solutions; each solution is customized for the distinct needs of a broad group of customers. This custom integration helps firms improve their customer portfolio and economics. It also helps improve cooperation among firms, for designing one-stop personalized solutions for customers. The opening case of Castrol is illustrative of this approach.

Network exchange systems: Firms act as network exchange systems by enabling other firms to find their customers directly using its technology or marketing platform. Network exchange system helps firms improve their overall network portfolio and economics. It also helps improve the market dominance of firms who are successful network exchanges.

Hax (2002) portrays the integrated approach of leveraging all three types of value strategies, in the shape of a triangle, referred to as the Delta model.

Driver: Network economics

Tactics: Gain complementor share

Consequence: Market dominance

Driver: Product economics

Tactics: Gain product share

Consequence: Rivalry

Driver: Customer economics

Tactics: Gain customer share

Consequence: Cooperation

Exhibit 4.x: Hax’s Delta Triangle – Integrating the Three Value Strategies

Two important system-level dimensions of value strategies are the issues of inclusions (micro-foundations) and of impacts (macro foundations). Whose resources, capabilities and core competencies are valued and included, and whose is not valued as much and excluded? What is the impact of the value linkages on economic, social and environmental criteria?

Exhibit 4.2 offers an integrated snapshot of the research on the meso-foundations of strategic advantage, based on this and the previous chapter.

Value System Analysis:

Inclusions (micro foundations)

Impacts (macro foundations)

Exhibit 4.2: Value Strategies for the New Economy

Product Stream Positions

Contemporary markets are hyper-competitive – technologies and globalization have intensified the competition among firms. As shown in Exhibit 4.x, in hyper-competitive markets, firms need to develop and introduce a stream of products on a continual basis. Else, they may not be able to sustain their competitive advantage. Faster product cycles require frequent disruption of value chains in order to avoid becoming too similar and undifferentiated commodities. To do so, investment is needed on an ongoing basis into research and development of innovative product streams. Firms, however, can’t afford to spread too thin and become too complex. They must consider ways to cash and phase out product streams with limited future potential. Each value chain in the stream achieves a best product positioning, improving the product economics.

| Emerging Product stream |

Customers |

| Growing Product stream | |

| Mauring Product stream |

Exhibit 4.x Product-based Value Streams : Increasing the Product Share

Each of the product streams may have a different business strategy. The business strategy may vary across the lifecycle of each product stream. Products in the emerging phase are often launched in a focus niche at a premium end (focus strategy. As they take-off, they may be offered to a broader market, although still with a premium associated with new product innovations (differentiation strategy). Further, with greater scalability, improved processes tend to improve cost-effectiveness, and allow the products to reach even the mass market. Gradually, as the scope for further scale is exhausted, lower cost becomes the key profitability driver (cost leadership strategy). Lastly, when a disruptive change in market or technology takes place, it becomes imperative to focus on market segments where the product continues to offer value for money (focus strategy).

Product life cycle analysis is an important tool to manipulate the economics of value strategies based on a stream of products. One way of applying this tool is through a typology of strategy profiles advanced by Miles and Snow (1978).

Miles and Snow Typology of Strategy Profiles

Firms face three basic problems in their value strategies.

The entrepreneurial problem: deciding value proposition and target markets

The engineering problem: designing value infrastructure, including technologies

The administrative problem: developing organizational and management structures

Firms may be classified into four strategy profiles, based on their approach to these problems. These are: the prospector, the analyzer, the defender, and the reactor.

The Prospector

A Prospector firm values being ‘first’ more than anything else. It thrives in VUCA environments – volatile, uncertain, complex, and ambiguous. A prospector firm addresses the entrepreneurial problem by testing new value propositions and new target markets. It manages the engineering problem by diversifying its value infrastructure and investing in multiple different technologies. It tackles the administrative problem by adopting decentralized and collaborative organizational structures with very flat management hierarchy. An exemplar prospector firm is 3M. Slater et al. (2010 p. 470) stated, “in 1916, 3M invented Wetordry… Other successful 3M discoveries include; masking tape, Scotch cellophane tape, the Thermo-Fax copying process, Scotchgard Fabric Protector, Post-it Notes and a variety of pharmaceutical products.”

The Analyzer

An analyzer firm is agile at quickly following prospectors into new domains. According to Slater et al. (2010 p. 475), Analyzers “target the early adopter and early majority segments with a creative strategy that enables the Analyzer to both steal early adopter customers from prospectors and attract members of the early majority”. An exemplar analyzer firm is Microsoft. Slater et al. (2010 p. 475) noted, “Microsoft has a very broad product line, with many of its best known products (e.g., DOS, Word, Excel, PowerPoint, Internet Explorer, X-Box) entering the market as second – or, even later – movers… Microsoft expends considerable effort identifying emerging product-market opportunities that have been established by traditional market innovators [Prospectors] – such as Apple, Sony, and Nintendo – and then pursuing sales in the mainstream market.”

The Defender

A defender firm manages the entrepreneurial problem by aggressively protecting their market share. It addresses engineering problem by specializing in a particular single core technology, standardizing its processes, and vertically integrating for cost efficiency. It tackles the Administrative problem through high degree of centralization, rigid and formal procedures, discrete functions, and lengthy, long-term planning processes ((Jurgens-Kowal, 2010). A firm exemplifying this approach is VIZIO, who during the 2000s became the market share leader with low manufacturing costs, low price, good quality, low advertising, and an intense focus on its distribution strategy. An example of the period where the defender strategy proved most successful was the 1960s and 1970s for the airline industry, because the government regulation resulted in minimum changes in the environment (Jurgens-Kowal, 2010).

The Reactor

A reactor firm does not address the problems of entrepreneurship, engineering or administration effectively. Major disruptive changes in markets or in technologies push many firms into the Reactor trap. These firms may perceive changes in the environment to be too drastic to allow for a deliberate response. An exemplar is the Finnish firm Nokia, that was once a leader in the mobile smartphones. However, with the shift towards Android and iOS based cellular technology, Nokia was unable to keep up and lost its advantage to Apple and Samsung.

Reinterpreting Miles and Snow (1978) Typology using the Dynamic Capabilities View

Miles and Snow (1978) held that firms develop a systematic, identifiable approach to environmental adaptation. They develop stable set of processes undergirding the value chain demands of the environments in which they operate. Therefore, when the value chain demands shift, firms face difficulties.

Sollosy (20131) re-examined Miles and Snow (1978) typology, and noted that Analyzers tend to have the ability to both develop new capabilities (explore) and improve existing capabilities (exploit). Firms that have the Analyzer capabilities are referred to as ambidextrous organizations (Tushman and O’Reilly’s, 1996). They develop a steady stream of new products-markets, while also finding creative ways to improve their processes. They engineer both radical as well as incremental innovations in their value chain processes, thereby generating a stream of value chains, each of which are being continuously improved.

In contrast, the Defenders tend to have a narrow and focused emphasis on exploitation, directing their attention to a limited segment of the potential market that they can protect. They tend to sustain the growth of this limited portfolio by engineering a continuous stream of incremental innovations.

Similarly, the Prospectors tend to have a narrow and focused emphasis on exploration, directing their attention on reputation for new product-market development. They continuously develop new products and markets, but are also quick to exit the older ones. Their exploration abilities allow them to engineer a constant stream of radical innovations.

Finally, the Reactors lack ability to consistently pursue an explorative focus (the Prospector), an exploitive focus (the Defender), or a systematic combination of the two (the Analyzer). Because of an inappropriate response to their environments, the Reactors face a permanently declining performance. Lacking strategic direction and facing resource erosions, they are neither able to explore new opportunities nor exploit their existing capabilities.

Custom Solutions Integrator

Contemporary markets are referred to as knowledge economy. Firms are moving away from selling standardized and isolated products to depersonalized customers and are offering integrated solutions comprising of customized products and services. Designing customized solutions requires the integrated concurrent processes that mobilize all relevant complementary resources, in place of the traditional sequential processes of a value chain. Custom solutions help customers achieve improved performance and economics through integrated services, thereby generating customer loyaltye (Hax, 2002). To offer total solutions to their customers, the firms need to work with and integrate not only their own product-based value chains, but also the value chains of diverse partners. As illustrated in Exhibit 4.x, value should be co-created with different players, instead of being sequentially created by suppliers, firms, and their customers.

| Partner/ Supplier | |

|

Customers Firm | |

| Partner/ Supplier |

Exhibit 4.x Custom Solution Integrators: Increasing the Customer Share

Exhibit 4.x illustrates how the world’s largest copper firm learnt the need to be a Custom Solutions Integrator, after it faced a growing threat of substitutes.

| Exhibit 4.x The World Copper Leader Learns to be a Custom Solutions Integrator Codelco (Corporación del Cobre) the largest and most profitable copper company in the world that is owned and managed by the Chilean government. During the 1990s, their competitive advantage was grounded primarily in the excellent quality of their copper mining plants. Their business strategy was to invest in the most effective cost infrastructure so that they could retain the significant cost advantage over their competitors. They were so cost efficient that they had to employ only six sales people to market $3 billion of copper annually, and they still believed they could deliver even with just four. This was possible because their customers were giant metal traders, with whom they had long-term contracts and relationships. They had no connections with or deep understanding of how the customers used copper. As all the major copper firms were similarly disconnected from the real needs and problems of the customers, the copper industry faced a growing threat of substitutes, such as aluminum, steel, plastic and fiber optics. The aluminum industry in particular had been investing in technologies for successfully substituting copper in many applications, such as the radiator and chassis in the auto industry. Recognizing the folly of its business strategy based solely on gaining a low cost leadership position in the value chain, Codelco decided to identify and form direct connections with the most innovative and largest multinational industrial users of copper, like Alcatel, ABB, Electrolux, Carrier, General Electric and Siemens. Source: Adapted from Hax (2002) |

To manipulate customer economics, custom solution integrators may pursue three distinct business strategies – with varying or equal emphasis (Hax, 2002).

Customer engagement: constantly innovate around the processes for segmenting their customers that reflect distinct priorities, and offer a differentiated treatment to each segment. For example: firms selling auto parts work intrinsically with auto assemblers to design, manufacture, and deliver parts that meet the particular specifications of each vehicle.

Customer integration: have a deep understanding as well the ability to solve customer problems either by themselves or with complementing partners, thereby enabling the customers to have a superior experience.

Customer shop: understand different products and services each customer needs and wants. Thus, their offer should include the entire gamut of products and services as a one-stop total service shop. For example: financial services firms offering the entire range of financial solutions to their customers.

Exhibit 4.x illustrates a leading consumer products firm that applied the Custom Solutions Integrator approach to redefine its value strategy for not only to its customers, but also its customers’ customers – i.e. the end users.

| Exhibit 4.x Extending the Custom Solutions Integrator Approach to Customers’ Customers For its Asian Home and Personal Care business division, Unilever identified three tiers of channel partners and three tiers of consumers that these partners serve. It has then developed a targeted approach to addressing the needs of each tier using different tactics. This approach has helped Unilever de-average its customers, and to de-commoditize the products and services it offers. Three tiers of Channel Partners Unilever identified three tiers of channel partners. Tier 1 comprises of powerful global retailers, such as Wal-Mart and Carrefour, who wield huge power on the suppliers in their home markets and enjoy a tremendous advantage in the terms of bargaining. Tier 2 comprises of regional and local modern-trade retailers, such as chain stores, who are enthusiastic to carry top brands offered by leading companies such as Unilever to pull in their customers. Tier 3 comprises of independent small local retailers, wholesalers and drug stores, which are fragmented and given low priority by major corporations. For Tier 1, Unilever uses its knowledge of the Asian market and its technological capabilities to offer a personalized portfolio of products for each of the local stores of the big global retailers. This allows it to foster a compelling win-win position. For Tier 2, Unilever offers customized reports on the changing customer preferences, and on products that are likely to grow in particular markets. This allows it to lock in the channel partners by helping them establish business in new markets, and manage these businesses effectively. For Tier 3, Unilever is investing in information technology and people for building connections, so that it is able to offer them a better service experience and improve their viability. The tiered approach has helped Unilever maintain a productive relationship with the top global retailers, to enjoy a consistent growth in the tier 2 channels, and to accelerate its growth using the tier 3 channels. As tier 3 channel partners grow into the mainstream, Unilever is well-placed not to be caught off-guarded and excluded. Three Tiers of Customers’s Customers – the End Consumers Unilever has also identified three tiers of end consumers. Tier 1 comprises of the most affluent members of society, who are price insensitive and have sophisticated needs in terms of quality of time, health, physical appearance, and vitality. Tier 2 is the upward socially mobile middle class who aspires to a better standard of living. Tier 3 is the deprived group of consumers who seek to satisfy basic and essential needs. Unilever is seeking to connect directly with the Tier 1 customers through beauty consultants situated in luxury retail chains and salons. These consultants are fully trained in the range of products offered by Unilever, and in offering personalized need assessment and application service to the end consumers. For the Tier 2 customers, Unilever is offering a range of products under different brands that are each in sync with the diverse emerging values and needs of the customers, thereby reaffirming their emotional lock-in. For the Tier 3 customers, it is working on including the members of the deprived communities in its value chain. It is introducing new product lines that offer value for money, and that come in affordable smaller packages for single use. Source: Adapted from Hax (2002) |

Network Exchange System

A third feature of contemporary markets is the role of inter-firm relationships and cooperative behaviors as an important source of value added service. The cost of collaboration has declined significantly as technology and globalization has reduced the transaction costs of doing business outside the boundaries of a firm. For instance, Intel must cultivate software developers who write applications that leverage the new processing capability, as well as hardware manufacturers who build systems that can accommodate the new chip. Close relationships with complementors encourage software developers to write applications to leverage the new chip capability.

In Network Exchange Systems, the emphasis is on adding value through interconnectivity with partners and end-customers. The interconnectivity can at times even be with competitors; for example: when a telecom firm offers interconnections to the networks of other competing telecom firms; or with complementors, like an airline offering interconnections to the networks of hotels and tourist operators to enable travelers to make a single booking for their entire travel arrangements.

Firms in a Network Exchange System are independent, yet cooperative relationships among them are critical. A notable example is Apple, who collaborates with Samsung for outsourcing some of the key components for its iphones, even as it is engaged in an acrimonious legal battle where it accuses Samsung of illegal and unauthorized use of its technologies in Samsung’s Galaxy smartphones. Customers also benefit from both explicit (such as social media platforms and applications like facebook and linkedin) and implicit (such as insurance firms that are able to offer lower premium protection by pooling risks across a larger network of customers) forms of exchanges.

Firms in Network Exchange Systems recognize that they cannot be successful by keeping their technological capabilities to themselves. They need to make them more accessible to allow other firms to design and manufacture a stream of innovative parts, applications, and services in a cost efficient, timely, and customer-focused way. Network Exchange Systems therefore democratize value linkages and offer better opportunities to smaller firms. Thus, they support the Long Tail hypothesis, which states that if the customers have an enhanced choice, they will gravitate towards niches because they satisfy focused needs better. As a result, the sales of low demand and uncommon products and services will exceed those of the relatively few current bestsellers and blockbusters (Anderson, 20062). For example, more than half of Amazon’s book sales come from outside its top 130,000 titles, which other bookstores typically stock in their physical stores. Similarly, more than half of Rhapsody’s music streams per month are outside its top 10,000 songs. Anderson (2009)3 notes how the network-effects and exchanges created by low-cost flights, online travel information and social-media driven word of mouth, are creating a long tail in the travel industry, as tourists explore less traveled destinations..

To manipulate network economics, Network Exchange Systems may pursue three distinct business strategies – with greater emphasis on one or equal emphasis on all (Hax, 2002).

Restricted channel: firms may develop exclusive relationships with complementors, thus restricting the ability of the competitors to offer effective solutions to the customers. This approach may not stand up to regulatory scrutiny, as it may have an unfair effect of hindering competition. A more effective approach is to build linkages with under-served and invisible channels. Wal-Mart, for instance, initially opened stores in isolated rural areas with 5,000 to 10,000 people – all rivals were ignoring these channels.

Dominant exchange: firms may provide an interface for exchange between buyers and sellers, making it difficult for any other firm to break-in. Wal-Mart, for instance, during its formative years as a rural chain, created a dominant exchange by investing in UPC code scanner, in RFID and other technologies. These allowed vendors to know which products were in greater demand and needed shelf replenishment more frequently, thereby assuring customers that the products they need will be available in a rural setting where stores tend to stock fewer items and fewer quantities of each item. Thus, both vendors and customers were locked-in.

Proprietary standard: firms may engage an extensive network of complementors to support their proprietary products, such as the app providers of Apple iphone.

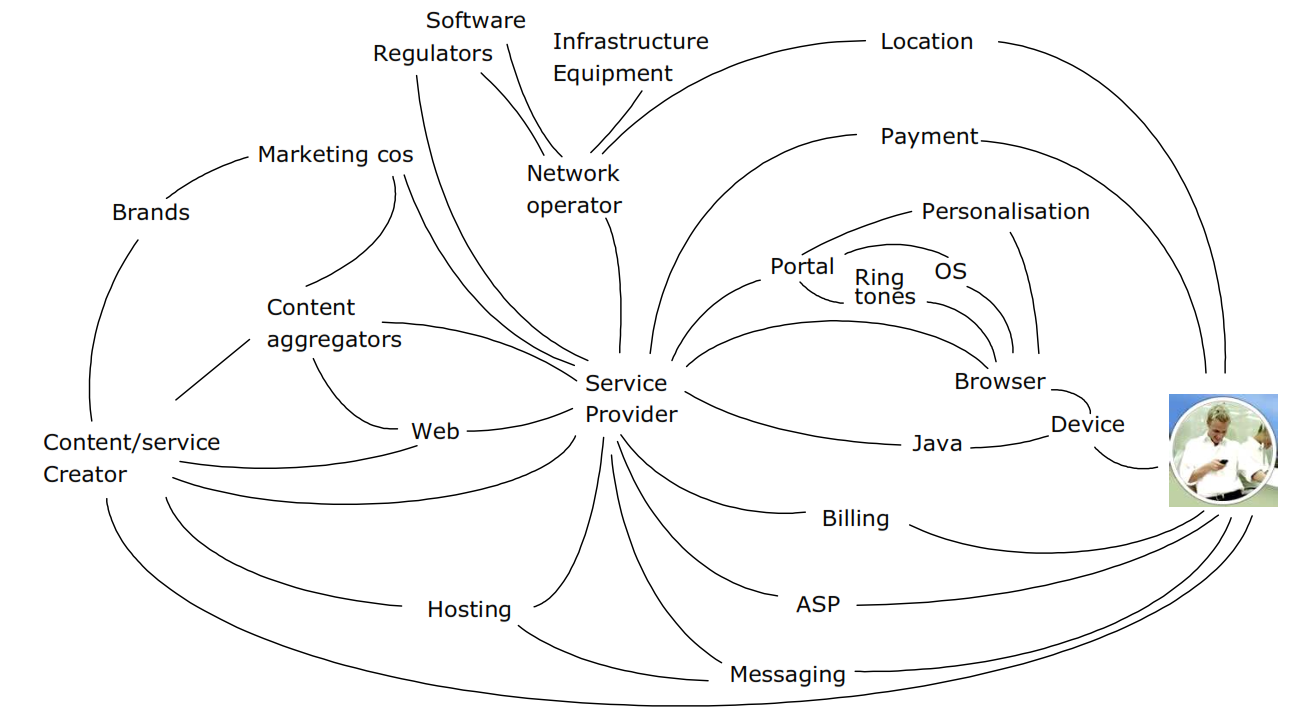

Value exchanges can be portrayed using a Value map of direct and indirect linkages among different participants (Peppard and Ryland, 2006). Exhibit 4.x illustrates how telecom operators have become Network exchange systems.

| Exhibit 4.x Telecom Operators Become Network Exchange Systems Traditionally, the large European and US mobile operators pursued “content ownership” or “content control” strategies, working with a small number of content owners and aggregators. However, because of the Long Tail, the stranglehold of the big content providers over operators and service providers is diminishing. The risks of Big hits strategy are increasing, and it is becoming more profitable to offer a wide variety of content from many different sources. The mobile operators are being challenged to shift their view of connection to customers as a ‘dumb pipe’ to a ‘smart pipe”, by brokering out their key assets such as search, personalization, and device management to content developers. Further, they are being challenged to design new value sharing arrangements with various exchange participants, in order to facilitate the flow of resources and knowledge throughout the network. Increasingly, network operators are not providing all content and services themselves. Some are being bundled from third-party providers, while customers are choosing their own providers for the others. Some of the content and service providers are conglomerate media organizations, others are smaller start-ups or aggregators. The walled-garden approach, where the network operators select specific providers to provide them with content and service, which they then integrate with their own network platform for delivery to the customers, is no longer viable. The customers want choice, variety, and control over the cost, ease, speed, and security of access to content and services. But the customers are also not interested in the complexity of the mobile systems and transmission network. To address customer needs, network operators form service level agreements with multiple third-party content and service providers, which allow them to secure more granular segmented content and service for various focused target markets.

Network Exchange System for a Mobile Operator Source: Peppard & Ryland, 2006 |

1 Sollosy, M (2013). A Contemporary Examination Of The Miles And Snow Strategic Typology Through The Lenses Of Dynamic Capabilities And Ambidexterity. Unpublished Doctoral Dissertation. Coles College of Business, Kennesaw State University, Kennesaw, GA.

2 Anderson, C. (2006). The Long Tail: Why the Future of Business is Selling Less of More, New York, NY: Hyperion.

3 Anderson, C (October 2, 2009). “The Long Trail of Travel” Wired Blog Network, http://www.longtail.com.