Ethics and Race

Chapter 2

Viewing Ethical Dilemmas Through Multiple Paradigms

According to John Dewey (1902), ethics is the science that deals with conduct insofar as this is considered to be right or wrong, good or bad. Ethics comes from the Greek word ethos, which means customs or usages, especially belonging to one group as distinguished from another. Later, ethics came to mean disposition or character, customs, and approved ways of acting. Looking at this definition from a critical perspective, one might ask: Ethics approved by whom? Right or wrong according to whom?

In this chapter, in an attempt to answer these and other important questions, we turn to three kinds of ethics emanating from diverse traditions that impact on education in general and educational leadership in particular. These paradigms include ethics from three viewpoints: justice, critique, and care. To these we add a fourth model, that of the ethic of the profession. What follows is a broad overview of the ethics of justice, critique, and care, and a more detailed explanation of the ethic of the profession.

Regarding the ethics of justice, critique, and care, we would like you to keep in mind that these are broad descriptions. Our intent for these three kinds of ethics is to provide enough of an introduction to the paradigms or models to enable you to receive a general sense of each of them. In an effort to be brief, we have had to leave out some outstanding scholars whose works are related to each of the paradigms. For in-depth coverage of scholars and their work regarding the ethics of justice, critique, and care, we suggest that you turn to our references in this book, locate other readings related to the models, and move beyond these introductory remarks.

In the case of the ethic of the profession, however, special attention is given to this paradigm. We do this because we believe there has been a gap in the educational leadership literature in using the paradigm of professional ethics to help solve moral dilemmas. All too frequently, the ethic of the profession is seen as simply a part of the justice paradigm. We do not believe this is so, and we want to make the argument that this form of ethics can be used separately as a fourth lens for reflecting on, and then dealing with, dilemmas faced by educational leaders. Therefore, what we present in this chapter is a more involved discussion of the ethic of the profession than of the other three paradigms.

THE ETHIC OF JUSTICE

The ethic of justice focuses on rights and law and is part of a liberal democratic tradition that, according to Delgado (1995), “is characterized by incrementalism, faith in the legal system, and hope for progress” (p. 1). The liberal part of this tradition is defined as a “commitment to human freedom,” and the democratic aspect implies “procedures for making decisions that respect the equal sovereignty of the people” (Strike, 1991, p. 415).

Starratt (1994b) described the ethic of justice as emanating from two schools of thought, one originating in the 17th Century, including the work of Hobbes and Kant and more contemporary scholars such as Rawls and Kohlberg; the other rooted in the works of philosophers such as Aristotle, Rousseau, Hegel, Marx, and Dewey. The former school considers the individual as central and sees social relationships as a type of a social contract where the individual, using human reason, gives up some rights for the good of the whole or for social justice. The latter tends to see society, rather than the individual, as central and seeks to teach individuals how to behave throughout their life within communities. In this tradition, justice emerges from “communal understandings” (p. 50).

Philosophers and writers coming from a justice perspective frequently deal with issues such as the nature of the universe, the nature of God, fate versus free will, good and evil, and the relationship between human beings and their state. Beauchamp and Childress (1984) and Crittenden (1984) describe competitive concepts related to the ethic of justice. Although acknowledging other perspectives and their positive aspects in their writings, Beauchamp and Childress, and Crittenden return to the ethic of justice and argue that educational leaders in societies whose governments are committed to certain fundamental principles, such as tolerance and respect for the fair treatment of all individuals, can and should look to laws and public policies for ethical guidance (Beck & Murphy, 1994b, p. 7).

Educators and ethicists from the ethic of justice have had a profound impact on approaches to education and educational leadership. Contemporary ethical writings in education, using the foundational principle of the ethic of justice, include, among others, works by Beauchamp and Childress (1984); Goodlad, Soder, and Sirotnik (1990); Kohlberg (1981); Sergiovanni (1992); Strike (2006); and Strike, Haller, and Soltis (1998).

Kohlberg (1981) argued that, within the liberal tradition, “there is a great concern not only to make schools more just—that is, to provide equality of educational opportunity and to allow freedom of belief—but also to educate so that free and just people emerge from schools” (p. 74). For Kohlberg, “justice is not a rule or set of rules, it is a moral principle … a mode of choosing that is universal, a rule of choosing that we want all people to adopt always in all situations” (p. 39). From this perspective, education is not “value-free.” This model also indicates that schools should teach principles, in particular those of justice, equity, and respect for liberty.

From the late 1960s through the early 1980s, Kohlberg introduced his “just community” approach to the schools. In institutions as diverse as Roosevelt High, a comprehensive school in Manhattan, The Bronx High School of Science, and an alternative high school in Cambridge, Massachusetts, students and teachers handled school discipline and sometimes even the running of the school together. In a civil and thoughtful manner, students were taught to deal with problems within the school, turning to rules, rights, and laws for guidance (Hersh, Paolitto, & Reimer, 1979).

Building on Kohlberg’s “just community,” Sergiovanni (1992) called for moral leadership and, in particular, the principle of justice in the establishment of “virtuous schools.” Sergiovanni viewed educational leadership as a stewardship and asked educational administrators to create institutions that are just and beneficent. By beneficence, Sergiovanni meant that there should be deep concern for the welfare of the school as a community, a concept that extends beyond the school walls and into the local community, taking into account not only students, teachers, and administrators, but families as well.

Unlike a number of educators in the field, Sergiovanni (1992) placed the principle of justice at the center of his concept of school. “Accepting this principle meant that every parent, teacher, student, administrator, and other member of the school community must be treated with the same equality, dignity, and fair play” (pp. 105–106).

The ethic of justice, from either a traditional or contemporary perspective, may take into account a wide variety of issues. Viewing ethical dilemmas from this vantage point, one may ask questions related to the rule of law and the more abstract concepts of fairness, equity, and justice. These may include, but are certainly not limited to, questions related to issues of equity and equality; the fairness of rules, laws, and policies; whether laws are absolute, and if exceptions are to be made, under what circumstances; and the rights of individuals versus the greater good of the community.

Moreover, the ethic of justice frequently serves as a foundation for legal principles and ideals. This important function is evident in laws related to education. In many instances, courts have been reluctant to impose restrictions on school officials, thus allowing them considerable discretion in making important administrative decisions (Board of Education v. Pico, 1981). At the same time, court opinions often reflect the values of the education community and society at large (Stefkovich & Guba, 1998). For example, only in recent years have courts upheld the use of metal detectors in schools to screen for weapons (People v. Dukes, 1992). In addition, what is legal in some places may be considered illegal in others. For instance, corporal punishment is still legal in 20 states and strip searching is legal in all but seven (Center for Effective Discipline, 2010; Hyman & Snook, 1999). In those states, it is left up to school officials, and the community, whether such practices are to be supported or not. Here, ethical issues such as due process and privacy rights are often balanced against the need for civility and the good of the majority.

Finally, what is to be done when a law is wrong, such as earlier Jim Crow laws supporting racial segregation (Starratt, 1994c; Stefkovich, 2006)? Under these circumstances, one must turn to ethics to make fair and just decisions. It is also in such instances that the ethic of justice may overlap with other paradigms such as the ethics of critique (Purpel, 1989, 2004) and care (Katz et al., 1999; Meyers, 1998; Sernak, 1998). Overall, the ethic of justice considers questions such as: Is there a law, right, or policy that relates to a particular case? If there is a law, right, or policy, should it be enforced? And if there is not a law, right, or policy, should there be one?

THE ETHIC OF CRITIQUE

Many writers and activists (e.g., Apple, 1986, 2000, 2001, 2003; Bakhtin, 1981; Bowles & Gintis, 1988; Foucault, 1983; Freire, 1970, 1993, 1998; Giroux, 1994, 2000, 2003; Greene, 1988; Purpel & Shapiro, 1995; Shapiro, 2009; Shapiro & Purpel, 2005) are not convinced by the analytic and rational approach of the justice paradigm. Some of these scholars find a tension between the ethic of justice, rights, and laws and the concept of democracy. In response, they raise difficult questions by critiquing both the laws themselves and the process used to determine if the laws are just.

Rather than accepting the ethic of those in power, these scholars challenge the status quo by seeking an ethic that will deal with inconsistencies, formulate the hard questions, and debate and challenge the issues. Their intent is to awaken us to our own unstated values and make us realize how frequently our own morals may have been modified and possibly even corrupted over time. Not only do they force us to rethink important concepts such as democracy, but they also ask us to redefine and reframe other concepts such as privilege, power, culture, language, and even justice.

The ethic of critique is based on critical theory, which has, at its heart, an analysis of social class and its inequities. According to Foster (1986), “Critical theorists are scholars who have approached social analysis in an investigative and critical manner and who have conducted investigations of social structure from perspectives originating in a modified Marxian analysis” (p. 71). More recently, critical theorists have turned to the intersection of race and gender as well as social class in their analyses.

An example of the work of critical theorists may be found in their arguments, occurring over many decades, that schools reproduce inequities similar to those in society (Bourdieu, 1977, 2001; Lareau, 1987, 2003). Tracking, for example, may be seen as one way to make certain that working-class children know their place (Oakes, 1993). Generally designed so that students are exposed to different knowledge in each track, schools “[make] decisions about the appropriateness of various topics and skills and, in doing so … [limit] … sharply what some students would learn” (p. 87). Recognizing this inequity, Carnoy and Levin (1985) pointed to an important contradiction in educational institutions, in that schools also represent the major force in the United States for expanding economic opportunity as well as the extension of democratic rights. Herein lies one of many inconsistencies to be addressed through the ethic of critique.

Along with critical theory, the ethic of critique is also frequently linked to critical pedagogy (Freire, 1970, 1993, 1998). Giroux (1991) asked educators to understand that their classrooms are political as well as educational locations and, as such, ethics is not a matter of individual choice or relativism but a “social discourse grounded in struggles that refuse to accept needless human suffering and exploitation” (p. 48). In this respect, the ethic of critique provides “a discourse for expanding basic human rights” (p. 48) and may serve as a vehicle in the struggle against inequality. In this vein, critical theorists are often concerned with making known the voices of those who are silenced, particularly students (Giroux, 1988, 2003; Weis & Fine, 1993).

For Giroux (1991, 2000, 2003, 2006), Welch (1991), and other critical educators, the language of critique is central, but discourse alone will not suffice. These scholars are also activists who believe discourse should be a beginning leading to some kind of action—preferably political. For example, Shapiro and Purpel (1993, 2005) emphasized empowering people through the discussion of options. Such a dialogue would hopefully provide what Giroux and Aronowitz (1985) called a “language of possibility” that, when applied to educational institutions, might enable them to avoid reproducing the “isms” in society (i.e., classism, racism, sexism, heterosexism).

Turning to educational leadership in particular, Parker and Shapiro (1993) argued that one way to rectify some wrongs in school and in society would be to give more attention to the analysis of social class in the preparation of principals and superintendents. They believed that social class analysis “is crucial given the growing divisions of wealth and power in the United States, and their impact on inequitable distribution of resources both within and among school districts” (pp. 39–40). Through the critical analysis of social class, there is the possibility that more knowledgable, moral, and sensitive educational leaders might be prepared.

Capper (1993), in her writings on educational leadership, stressed the need for moral leaders to be concerned with “freedom, equality, and the principles of a democratic society” (p. 14). She provided a useful summary of the roots of, and philosophy supporting, the ethic of critique as it pertains to educational leaders. She spoke of the Frankfurt school in the United States in the 1920s, in which immigrants tried to make sense of the oppression they had endured in Europe. This school provided not only a Marxist critique but took into account psychology and its effect on the individual. Capper (1993, p. 15) wrote:

Grounded in the work of the Frankfurt school, critical theorists in educational administration are ultimately concerned with suffering and oppression, and critically reflect on current and historical social inequities. They believe in the imperative of leadership and authority and work toward the empowerment and transformation of followers, while grounding decisions in morals and values.

Thus, by demystifying and questioning what is happening in society and in schools, critical theorists may help educators rectify wrongs while identifying key morals and values.

In summary, the ethic of critique, inherent in critical theory, is aimed at awakening educators to inequities in society and, in particular, in the schools. This ethic asks educators to deal with the hard questions regarding social class, race, gender, and other areas of difference, such as: Who makes the laws? Who benefits from the law, rule, or policy? Who has the power? Who are the silenced voices? This approach to ethical dilemmas then asks educators to go beyond questioning and critical analysis to examine and grapple with those possibilities that could enable all children, whatever their social class, race, or gender, to have opportunities to grow, learn, and achieve. Such a process should lead to the development of options related to important concepts such as oppression, power, privilege, authority, voice, language, and empowerment.

THE ETHIC OF CARE

Juxtaposing an ethic of care with an ethic of justice, Roland Martin (1993, p. 144) wrote the following:

One of the most important findings of contemporary scholarship is that our culture embraces a hierarchy of value that places the productive processes of society and their associated traits above society’s reproductive processes and the associated traits of care and nurturance. There is nothing new about this. We are the inheritors of a tradition of Western thought according to which the functions, tasks, and traits associated with females are deemed less valuable than those associated with males.

Some feminist scholars (e.g., Beck, 1994; Belenky, Clinchy, Goldberger, & Tarule, 1986; Gilligan, 1982; Gilligan, Ward, & Taylor, 1988; Ginsberg, Shapiro, & Brown, 2004; Goldberger, Tarule, Clinchy, & Belenky, 1996; Grogan, 1996; Larson & Murtadha, 2002; Marshall, 1995; Marshall & Gerstl-Pepin, 2005; Marshall & Oliva, 2006; Noddings, 1992, 2002, 2003; Noddings, Stengel, & Alan, 2006; Sernak, 1998; Shapiro & Smith-Rosenberg, 1989; Shapiro, Ginsberg, & Brown, 2003) have challenged this dominant, and what they consider to be often patriarchal, ethic of justice in our society by turning to the ethic of care for moral decision making. Attention to this ethic can lead to other discussions of concepts such as loyalty, trust, and empowerment. Similar to critical theorists, these feminist scholars emphasize social responsibility, frequently discussed in the light of injustice, as a pivotal concept related to the ethic of care.

In her classic book In a Different Voice, Gilligan (1982) introduced the ethic of care by discussing a definition of justice different from Kohlberg’s in the resolution of moral dilemmas (see the ethic of justice section in this chapter). In her research, Gilligan discovered that, unlike the males in Kohlberg’s studies who adopted rights and laws for the resolution of moral issues, women and girls frequently turned to another voice, that of care, concern, and connection, in finding answers to their moral dilemmas. Growing out of the ethic of justice, the ethic of care, as it relates to education, has been described well by Noddings (1992), who created a new educational hierarchy placing “care” at the top when she wrote, “The first job of the schools is to care for our children” (p. xiv). To Noddings, and to a number of other ethicists and educators who advocate the use of the ethic of care, students are at the center of the educational process and need to be nurtured and encouraged, a concept that likely goes against the grain of those attempting to make “achievement” the top priority. Noddings believes that holding on to a competitive edge in achievement means that some children may see themselves merely as pawns in a nation of demanding and uncaring adults. In school buildings that more often resemble large, bureaucratic, physical plants, a major complaint of young people with regard to adults is, “They don’t care!” (Comer, 1988). For Noddings, “Caring is the very bedrock of all successful education and … contemporary schooling can be revitalized in its light” (1992, p. 27).

Noddings and Gilligan are not alone in believing that the ethic of care is essential in education. In relation to the curriculum, Roland Martin (1993) wrote of the three Cs of caring, concern, and connection. Although she did not ask educators to teach “Compassion 101a” or to offer “Objectivity 101a,” she did implore them to broaden the curriculum to include the experiences of both sexes, and not just one, and to stop leaving out the ethic of care. For Roland Martin, education is an “integration of reason and emotion, self and other” (p. 144).

Although the ethic of care has been associated with feminists, men and women alike attest to its importance and relevancy. Beck (1994) pointed out that “caring—as a foundational ethic—addresses concerns and needs as expressed by many persons; that it, in a sense, transcends ideological boundaries” (p. 3). Male ethicists and educators, such as Buber (1965), Normore (2008), and Sergiovanni (1992), have expressed high regard for this paradigm. These scholars have sought to make education a “human enterprise” (Starratt, 1991, p. 195).

Some scholars have recently associated the ethic of care with the philosophy of utilitarianism. For example, Blackburn (2006) believes that Bentham, Mills, and Hume spoke of the ethic of care as part of the public sphere. The concept of the greatest happiness of the greatest number, according to Blackburn (2001, p. 93), moved care into the civic realm. He wrote:

An ethic of care and benevolence, which is essentially what utilitarianism is, gives less scope to a kind of moral philosophy modeled on law, with its hidden and complex structures and formulae known only to the initiates.

The ethic of care is important not only to scholars but to educational leaders who are often asked to make moral decisions. If the ethic of care is used to resolve dilemmas, then there is a need to revise how educational leaders are prepared. In the past, educational leaders were trained using military and business models. This meant that they were taught about the importance of the hierarchy and the need to follow those at the top, and, at the same time, to be in command and in charge of subordinates (Guthrie, 1990). They led by developing “rules, policies, standard operating procedures, information systems … or a variety of more informal techniques” (Bolman & Deal, 1991, p. 48). These techniques and rules may have worked well when the ethic of justice, rights, and laws was the primary basis for leaders making moral decisions; however, they are inadequate when considering other ethical paradigms, such as the ethic of care, that require leaders to consider multiple voices in the decision-making process.

Beck (1994) stressed that it is essential for educational leaders to move away from a top–down, hierarchical model for making moral and other decisions and, instead, to turn to a leadership style that emphasizes relationships and connections. Administrators need to “encourage collaborative efforts between faculty, staff, and students [which would serve] … to promote interpersonal interactions, to deemphasize competition, to facilitate a sense of belonging, and to increase individuals’ skills as they learn from one another” (p. 85).

When an ethic of care is valued, educational leaders can become what Barth (1990) called, “head learner(s)” (p. 513). What Barth meant by that term was the making of outstanding leaders and learners who wish to listen to others when facing the need to make important moral decisions. The preparation of these individuals, then, must more heavily focus on the knowledge of cultures and of diversity, with a special emphasis on learning how to listen, observe, and respond to others. For example, Shapiro, Sewell, DuCette, and Myrick (1997), in their study of inner-city youth, identified three different kinds of caring: attention and support; discipline; and “staying on them,” or prodding them over time. Although prodding students to complete homework might be viewed as nagging, the students these researchers studied saw prodding as an indication that someone cared about them.

Thus, the ethic of care offers another perspective and other ways to respond to complex moral problems facing educational leaders in their daily work. One aspect of its intricacy is that this lens tends to sometimes deal with emotions. Highlighting this complexity, Paul Begley, an educational ethicist, raised the question: Is the ethic of care an emotional or rational model? Thinking through this important question, it became clear that aspects of this ethic could be considered rational, such as providing discipline and attention to students; however, empathy and compassion toward others are also part of this paradigm and tend to demonstrate emotions. Hence, portions of this model coincide well with the emerging brain research regarding decision making, in general, in which emotions and reason are blended in intricate ways (Lehrer, 2009).

Viewing ethical dilemmas through the ethic of care may prompt questions related to how educators may assist young people in meeting their needs and desires and will reflect solutions that show a concern for others as part of decision making. This ethic asks that individuals consider the consequences of their decisions and actions. It asks them to consider questions such as: Who will benefit from what I decide? Who will be hurt by my actions? What are the long-term effects of a decision I make today? And if I am helped by someone now, what should I do in the future about giving back to this individual or to society in general? This paradigm also asks individuals to grapple with values such as loyalty and trust.

THE ETHIC OF THE PROFESSION

Starratt (1994b) postulated that the ethics of justice, care, and critique are not incompatible, but rather, complementary, the combination of which results in a richer, more complete, ethic. He visualized these ethics as themes, interwoven much like a tapestry:

An ethical consciousness that is not interpenetrated by each theme can be captured either by sentimentality, by rationalistic simplification, or by social naivete. The blending of each theme encourages a rich human response to the many uncertain ethical situations the school community faces every day, both in the learning tasks as well as in its attempt to govern itself. (p. 57)

We agree with Starratt; but we have also come to believe that, even taken together, the ethics of justice, critique, and care do not provide an adequate picture of the factors that must be taken into consideration as leaders strive to make ethical decisions within the context of educational settings. What is missing—that is, what these paradigms tend to ignore—is a consideration of those moral aspects unique to the profession and the questions that arise as educational leaders become more aware of their own personal and professional codes of ethics. To fill this gap, we add a fourth to the three ethical frameworks described in this chapter: a paradigm of professional ethics.

Although the idea of professional ethics has been with us for some time, identifying the process as we have and presenting it in the form of a paradigm represents an innovative way of conceptualizing this ethic. Because this approach is relatively new—one which we have developed through more than a decade of collaborative research, writing, and teaching ethics—we devote more time to explaining this ethic than was given to others. The remainder of this chapter includes some brief background information on the emergence of professional ethics and the need for a professional ethics paradigm. Following these introductory remarks, we describe our model of professional ethics and how it works. This chapter concludes with a discussion of how the paradigm of professional ethics fits in with the other three ethics of justice, critique, and care.

PROFESSIONAL ETHICS AND THE NEED FOR A PROFESSIONAL PARADIGM

When discussing ethics in relation to the professionalization of educational leaders, the tendency is to look toward professions such as law, medicine, dentistry, and business, which require their graduate students to take at least one ethics course before graduation as a way of socializing them into the profession. The field of educational administration has no such ethics course requirement.

However, in recent years there has been an interest in ethics in relation to educational decision making. A number of writers in educational administration (Beck, 1994; Beck & Murphy, 1994a, 1994b; Beck, Murphy, & Associates, 1997; Beckner, 2004; Begley, 1999; Begley & Johansson, 1998, 2003; Cambron-McCabe & Foster, 1994; Duke & Grogan, 1997; Greenfield, 2004; Mertz, 1997; Murphy, 2006; O’Keefe, 1997; Starratt, 1994b; Willower, 1999) believe it is important to provide prospective administrators with some training in ethics. As Greenfield (1993) pointed out, this preparation could “enable a prospective principal or superintendent to develop the attitudes, beliefs, knowledge, and skills associated with competence in moral reasoning” (p. 285). Stressing the importance of such preparation, Greenfield left us with a warning of sorts:

A failure to provide the opportunity for school administrators to develop such competence constitutes a failure to serve the children we are obligated to serve as public educators. As a profession, educational administration thus has a moral obligation to train prospective administrators to be able to apply the principles, rules, ideals, and virtues associated with the development of ethical schools. (p. 285)

Recognizing this need, ethics was identified as one of the competencies necessary for school leaders in the document, Interstate School Leaders Licensure Consortium: Standards for School Leavers (NPBEA, 1996). This document, developed by the consortium, under the auspices of the Council of Chief State School Officers and in collaboration with the National Policy Board for Educational Administration (NPBEA), was produced by representatives from 24 states and nine associations related to the educational administration profession.

More recently, in a revised document, Educational Leadership Policy Standards (NPBEA, 2008), school leaders again set forth six standards for the profession. Of these, Standard 5 remained: “An education leader promotes the success of every student by acting with integrity, fairness, and in an ethical manner.” Slightly modified from its 1996 document, it goes on to add the following functions:

A. Ensure a system of accountability for every student’s academic and social success; B. Model principles of self-awareness, reflective practice, transparency, and ethical behavior; C. Safeguard the values of democracy, equity, and diversity; D. Consider and evaluate the potential moral and legal consequences of decision-making; and E. Promote social justice and ensure that individual student needs inform all aspects of schooling. (NPBEA, 2008, pp. 4–5)

Although there are some changes from the 1996 version, this standard, with its functions, officially continues to recognize the importance of ethics in the knowledge base for school administrators. Commensurate with these standards, many states now require principals to pass an exam measuring related competencies, including ethics, and these standards are now incorporated into the National Association for the Accreditation of Teacher Education (NCATE; Murphy, 2005).

In the past, professional ethics has generally been viewed as a subset of the justice paradigm. This is likely the case because professional ethics is often equated with codes, rules, and principles, all of which fit neatly into traditional concepts of justice (Beauchamp & Childress, 1984). For example, many states have established their own sets of standards. The Pennsylvania Code of Professional Practice and Conduct for Educators (1992) is an 11-point code of conduct that was subsequently enacted into state law. Texas has a similar code of ethics, standards, and practices (Texas Administrative Code, 1998) for its educators that, among other things, expects them to deal justly with students and protect them from “disparagement.”

In addition, a number of education-related professional organizations have developed their own professional ethical codes. Defined by Beauchamp and Childress (1984) as “an articulated statement of role morality as seen by members of the profession” (p. 41), some of these ethical codes are relatively new and others are long-standing. Examples of these organizations include, but are certainly not limited to, the American Association of School Administrators, the American Association of University Professors, the American Psychological Association, the Association of School Business Officials, the Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development, and the National Education Association.

However, ethical codes set forth by the states and professional associations tend to be limited in their responsiveness in that they are somewhat removed from the day-to-day personal and professional dilemmas which educational leaders face. Nash (1996), in his book on professional ethics for educators and human service professionals, recognized these limitations as he observed his students’ lack of interest in such codes:

What are we to make of this almost universal disparagement of professional codes of ethics? What does the nearly total disregard of professional codes mean? For years, I thought it was something in my delivery that evoked such strong, antagonistic responses. For example, whenever I ask students to bring their codes to class, few knew where to locate them, and most get utterly surly when I make such a request. I understand, now, however, that they do not want to be bothered with what they consider a trivial, irrelevant assignment, because they simply do not see a correlation between learning how to make ethical decisions and appealing to a code of ethics. (p. 95)

On the other hand, professional codes of ethics serve as guideposts for the profession, giving statements about its image and character (Lebacqz, 1985). They embody “the highest moral ideals of the profession,” thus “presenting an ideal image of the moral character of both the profession and the professional” (Nash, 1996, p. 96). Seen in this light, standardized codes provide a most valuable function. Thus, the problem lies not so much in the codes themselves, but in the fact that we sometimes expect too much from them with regard to moral decision making (Lebacqz, 1985; Nash, 1996).

The University Council of Educational Administration has recognized the need for a code that is developed in a participatory fashion and is not static (UCEA Ethical Code Committee, 2004–2009). This organization is developing a code, using the internet and continual committee meetings over time, which will hopefully provide an ongoing set of principles in response to some of the current criticisms of organizational codes.

Recognizing the importance of standardized codes, the contributions they make, and their limitations, we believe the time has come to view professional ethics from a broader, more inclusive, and more contemporary perspective. This type of approach is reflected in the ISLLC Standards. Focusing on rules, principles, and identification of competencies, these standards are essentially regulatory in nature. At the same time, they acknowledge the importance of knowing different ethical frameworks. In addition, competence for the profession is assessed through an examination based on a case study approach; that is, an analysis of vignettes asking what factors a school leader should consider in making a decision.

A PARADIGM FOR PROFESSIONAL ETHICS

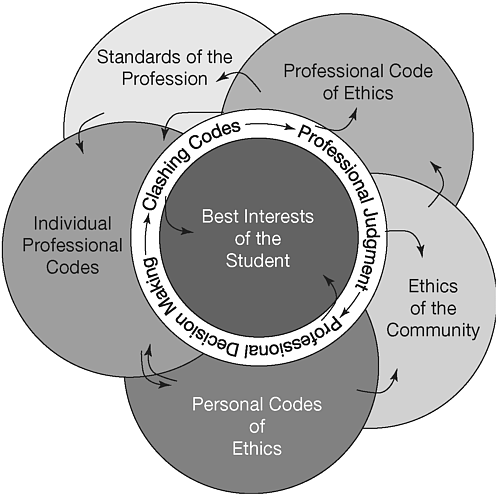

Our concept of professional ethics as an ethical paradigm includes ethical principles and codes of ethics embodied in the justice paradigm, but is much broader, taking into account other paradigms, as well as professional judgment and decision making.

We recognize professional ethics as a dynamic process requiring administrators to develop their own personal and professional codes. We believe this process is important and, like Nash, we observed a dissonance between students’ own codes and those set forth by states or professional groups. For the most part, our students were not aware of these codes or, if they were, such formalized professional codes had little impact on them; most found it more valuable to create their own codes. As one of our students, a department chair, pointed out after his involvement in this process:

Surprisingly to me, I even enjoyed doing the personal and professional ethics statements. I have been in union meetings where professional ethical codes were discussed. They were so bland and general as to be meaningless. Doing these statements forced me to think about what I do and how I live, whereas the previous discussions did not. It was a very positive experience. I also subscribe to the notion that [standardized] professional ethical codes are of limited value. I look to myself to determine what decisions I can live with. Outside attempts at control have little impact on me and what I do.

Through our work, we have come to believe that educational leaders should be given the opportunity to take the time to develop their own personal codes of ethics based on life stories and critical incidents. They should also create their own professional codes based on the experiences and expectations of their working lives as well as a consideration of their personal codes.

Underlying such a process is an understanding of oneself as well as others. These understandings necessitate that administrators reflect on concepts such as what they perceive to be right or wrong and good or bad, who they are as professionals and as human beings, how they make decisions, and why they make the decisions they do. This process recognizes that preparing students to live and work in the 21st Century requires very special leaders who have grappled with their own personal and professional codes of ethics and have reflected on diverse forms of ethics, taking into account the differing backgrounds of the students enrolled in U.S. schools and universities today. By grappling, we mean that these educational leaders have struggled over issues of justice, critique, and care related to the education of children and youth and, through this process, have gained a sense of who they are and what they believe personally and professionally. It means coming to grips with clashes that may arise among ethical codes and making ethical decisions in light of their best professional judgment, a judgment that places the best interests of the student at the center of all ethical decision making.

Thus, actions by school officials are likely to be strongly influenced by personal values (Begley, 1999; Begley & Johansson, 1998; Willower & Licata, 1997), and personal codes of ethics build on these values and experiences (Shapiro & Stefkovich, 1997, 1998). As many of our students found, it is not always easy to separate professional from personal ethical codes. The observations of this superintendent of a large rural district aptly sum up our own experiences and the sentiments of many of our practitioner-students:

A professional ethical code cannot be established without linkage and reference to one’s personal code of ethics and thereby acknowledges such influencing factors. In retrospect, and as a result of … [developing my own ethical codes], I can see the influence professional responsibilities have upon my personal values, priorities, and behavior. It seems there is an unmistakable “co-influence” of the two codes. One cannot be completely independent of the other. (Shapiro & Stefkovich, 1998, p. 137).

Other factors that play into the development of professional codes involve consideration of community standards, including both the professional community and the community in which the leader works; formal codes of ethics established by professional associations; and written standards of the profession (ISLLC).

As educational leaders develop their professional (and personal) codes, they consider various ethical models, either focusing on specific paradigms or, optimally, integrating the ethics of justice, care, and critique. This filtering process provides the basis for professional judgments and professional ethical decision making; it may also result in clashes among codes.

Through our work, we have identified four possible clashes, three of which have been discussed earlier (Shapiro & Stefkovich, 1998). First, there may be clashes between an individual’s personal and professional codes of ethics. This may occur when an individual’s personal ethical code conflicts with an ethical code set forth by the profession. Second, there may be clashes within professional codes. This may happen when the individual has been prepared in two or more professions. Codes of one profession may be different from another. Hence, a code that serves an individual well in one career may not in another. Third, there may be clashes of professional codes among educational leaders; what one administrator sees as ethical, another may not. Fourth, there may be clashes between a leader’s personal and professional code of ethics and custom and practices set forth by the community (either the professional community, the school community, or the community where the educational leader works). For example, a number of our students noted that some behavior that may be considered unethical in one community may, in another community, be seen merely as a matter of personal preference.

Furman (2003, 2004), expanding on what she characterizes as a separate “ethic of the community” and defining it as a process, asks leaders to move away from heroic (solo) decision making and to make decisions with the assistance of the community. Her definition of community is broad and all-encompassing, relating to a distributive model of leadership (Spillane, Halverson, & Diamond, 2001) as well as to participatory democracy.

To resolve the four clashes, we hark back to Greenfield’s earlier (1993) quote that grounded the “moral dimension” for the preparation of school administrators in the needs of children. Greenfield contended that schools, particularly public schools, should be the central sites for “preparing children to assume the roles and responsibilities of citizenship in a democratic society” (p. 268). To achieve Greenfield’s goal, we must also turn to teachers, in leadership positions, and their ethics (Burant, Chubbuck, & Whipp, 2007; Campbell, 2000, 2004; Hansen, 2001; Hostetler, 1997; Strike & Ternasky, 1993). Teacher leaders, such as heads of charter schools and learning communities or teacher coaches, need to be prepared as ethical professionals.

Not all those who write about the importance of the study of ethics in educational leadership discuss the needs of children; however, this focus on students is clearly consistent with the backbone of our profession. Other professions often have one basic principle driving the profession. In medicine, it is “First, do no harm.” In law, it is the assertion that all clients deserve “zealous representation.” In educational leadership, we believe that if there is a moral imperative for the profession, it is to serve the “best interests of the student.” Consequently, this ideal must lie at the heart of any professional paradigm for educational leaders.

This focus is reflected in most professional association codes. For example, the American Association of School Administrators’ Statement of Ethics for School Administrators (American Association of School Administrators, 1981) begins with the assertion, “An educational administrator’s professional behavior must conform to an ethical code” and has as its first tenet this statement: “The educational administrator … makes the well-being of students the fundamental value of all decision making and actions” [emphasis added]. It is in concert with Noddings’ (2003) ethic of care, which places students at the top of the educational hierarchy, and is reflective of the concerns of many critical theorists who see students’ voices as silenced (Giroux, 1988, 2003; Weis & Fine, 1993). In addition, serving the best interests of the student is consistent with the ISLLC’s standards for the profession, each of which begins with the words, “An education leader promotes the success of every student [emphasis added]” (NPBEA, 2008).

Frequent confrontations with moral dilemmas become even more complex as dilemmas increasingly involve a variety of student populations, parents, and communities comprising diversity in broad terms that extend well beyond categories of race and ethnicity. In this respect, differences encompassing cultural categories of race and ethnicity, religion, social class, gender, disability, and sexual orientation as well as individual differences that may take into account learning styles, exceptionalities, and age often cannot be ignored (Banks, 2001; Banks & Banks, 2006; Cushner,

Figure 2.1 Diagrammatic representation of the ethic of the profession.

Notes

The circles indicate major factors that converge to create the professional paradigm. The circles shown are: Standards of the Profession; Professional Code of Ethics; Ethics of the Community; Personal Codes of Ethics; Individual Professional Codes, and Best Interests of the Student. Other factors also play a part in the professional paradigm. They are found surrounding the Best Interests of the Student circle and include: Clashing Codes; Professional Judgment, and Professional Decision Making. The arrows indicate the various ways in which the factors interact and overlap with each other. McClelland, & Safford, 1992; Gollnick & Chinn, 1998; Shapiro et al., 2001; Sleeter & Grant, 2003).